Shisham (Dalbergia Sissoo) Decline by Dieback Disease, Root Pathogens and Their Management: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dalbergia Proposal Guatemala (Rev.2)

CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA CONSIDERATION OF PROPOSALS FOR AMENDMENT OF APPENDICES I AND II A. Proposal Inclusion of the genus Dalbergia in CITES Appendix II with exception to the species included in Appendix I. The UNEP-WCMC assessed the Dalbergia species of Latin America and concluded: “… all populations of Dalbergia spp. from South and Central America appear to meet the criteria for listing in CITES Appendix II” (UNEP-WCMC, 2015). Including the whole genus in Appendix II will be essential for the control of international trade by eliminating the arduous task of enforcement and customs officers of differentiating between the hundreds of Dalbergia species listed and not listed in CITES. The inclusion will help ensure that legal trade does not become a direct cause of the extinction of these highly threatened species and will help curb illegal trade. Considering that CITES Appendix II must include all species, which although not necessarily now threatened with extinction may become so unless trade in specimens of such species is subject to strict regulation in order to avoid utilization incompatible with their survival, it is important to include the genus Dalbergia in CITES Appendix II. a) Resolution Conf. 9.24, Annex 2 a, Criterion A - ”It is known, or can be inferred or projected, that the regulation of trade in the species is necessary to avoid it becoming eligible for inclusion in Appendix I in the near future”. b) Resolution Conf. 9.24, Annex 2 a, Criterion B - ”It is known, or can be inferred or projected, that regulation of trade in the species is required to ensure that the harvest of specimens from the wild is not reducing the wild population to a level at which its survival might be threatened by continued harvesting or other influences”. -

The Madagascar Rosewood Massacre

MADAGASCAR CONSERVATION & DEVELOPMENT VOLUME 4 | ISSUE 2 — DECEMBER 2009 PAGE 98 The Madagascar rosewood massacre Derek Schuurman and Porter P. Lowry III Correspondence: Derek Schuurman E - mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT centaines de tonnes par mois en 1998 à plus de 30,000 tonnes Valuable timber has been exploited from Madagascar’s entre juillet 2000 et juin 2001. Ces bois précieux ont presque rainforests for many decades, and Malagasy rosewood and tous été obtenus d’une exploitation illicite en provenant des palissandre (Dalbergia spp.) are among the most sought after aires protégées et plus particulièrement des Parcs Nationaux hardwoods in the world. Large quantities have been harvested de Marojejy et de Masoala dans la région SAVA (Sambava - and exported at an increasing rate over the last decade, almost Antalaha - Vohémar - Andapa) au nord - est de Madagascar. entirely from illegal logging in protected areas, in particular Ces parcs ont été récemment reconnus au titre de patrimoine Masoala and Marojejy National Parks, which comprise part of mondial de l’UNESCO dans la nouvelle région des forêts the newly - established Atsinanana UNESCO World Heritage Site humides de l’Atsinanana. Nous présentons des informa- in the SAVA (Sambava - Antalaha - Vohémar - Andapa) region tions obtenues de sources régionales qui montrent qu’une of northeast Madagascar. We present information obtained from organisation d’un trafic sans précédent de l’exploitation illégale sources in the region that documents an unprecedented, highly dans les -

Project Rapid-Field Identification of Dalbergia Woods and Rosewood Oil by NIRS Technology –NIRS ID

Project Rapid-Field Identification of Dalbergia Woods and Rosewood Oil by NIRS Technology –NIRS ID. The project has been financed by the CITES Secretariat with funds from the European Union Consulting objectives: TO SELECT INTERNATIONAL OR NATIONAL XYLARIUM OR WOOD COLLECTIONS REGISTERED AT THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF WOOD ANATOMISTS – IAWA THAT HAVE A SIGNIFICANT NUMBER OF SPECIES AND SPECIMENS OF THE GENUS DALBERGIA TO BE ANALYZED BY NIRS TECHNOLOGY. Consultant: VERA TERESINHA RAUBER CORADIN Dra English translation: ADRIANA COSTA Dra Affiliations: - Forest Products Laboratory, Brazilian Forest Service (LPF-SFB) - Laboratory of Automation, Chemometrics and Environmental Chemistry, University of Brasília (AQQUA – UnB) - Forest Technology and Geoprocessing Foundation - FUNTEC-DF MAY, 2020 Brasília – Brazil 1 Project number: S1-32QTL-000018 Host Country: Brazilian Government Executive agency: Forest Technology and Geoprocessing Foundation - FUNTEC Project coordinator: Dra. Tereza C. M. Pastore Project start: September 2019 Project duration: 24 months 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 05 2. THE SPECIES OF THE GENUS DALBERGIA 05 3. MATERIAL AND METHODS 3.1 NIRS METHODOLOGY AND SPECTRA COLLECTION 07 3.2 CRITERIA FOR SELECTING XYLARIA TO BE VISITED TO OBTAIN SPECTRAS 07 3 3 TERMINOLOGY 08 4. RESULTS 4.1 CONTACTED XYLARIA FOR COLLECTION SURVEY 10 4.1.1 BRAZILIAN XYLARIA 10 4.1.2 INTERNATIONAL XYLARIA 11 4.2 SELECTED XYLARIA 11 4.3 RESULTS OF THE SURVEY OF DALBERGIA SAMPLES IN THE BRAZILIAN XYLARIA 13 4.4 RESULTS OF THE SURVEY OF DALBERGIA SAMPLES IN THE INTERNATIONAL XYLARIA 14 5. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 19 6. REFERENCES 20 APPENDICES 22 APPENDIX I DALBERGIA IN BRAZILIAN XYLARIA 22 CACAO RESEARCH CENTER – CEPECw 22 EMÍLIO GOELDI MUSEUM – M. -

Brazilian Red Propolis: Legitimate Name of the Plant Resin Source

MOJ Food Processing & Technology Opinion Open Access Brazilian red propolis: legitimate name of the plant resin source Abstract Volume 6 Issue 1 - 2018 Red propolis ranks as the second most produced Brazilian propolis type. Its main chemical constituents are phenolic substances typical of the subfamily Faboideae of Antonio Salatino Maria Luiza F Salatino the Fabaceae (Leguminosae) family, such as neoflavanoids, chalcones, flavanones and Department of Botany, Institute of Biosciences, University of isoflavonoids, among them isoflavones (e.g. biochanin a, daidzein) and pterocarpans São Paulo, Brazil (e.g. medicarpin). The plant source of Brazilian red propolis has been referred to as Dalbergia ecastophyllum throughout the propolis literature. Such scientific binomial, Correspondence: Antonio Salatino, Department of Botany, Institute of Biosciences, University of São Paulo, Rua do Matão however, is a synonym of the legitimate name Dalbergia ecastaphyllum. 277, 05508-090, São Paulo, SP, Brazil, Tel (+5511)3091-7532, Keywords: botanical origin, brazilian propolis, dalbergia ecastaphyllum, Email [email protected] isoflavonoids, legitimate name, medicarpin, neoflavonoids, phenolic compounds, Received: January 03, 2018 | Published: January 08, 2018 synonym Introduction caffeoylquinic acids predominated as its main constituents. Brazilian green propolis is consumed domestically and exported to several Propolis is a product from honey bee hives, containing chiefly countries, mainly to Japan and China. beeswax and a resin obtained from diverse plant sources, such as apical buds, young leaves and exudates. Color, smell and texture Brazilian red propolis vary according to propolis types and plant sources. Beginning in the last decade of the last century the number of publications about This type of propolis was chemically and botanically characterized 9,10 propolis escalated, giving rise to successive reviews about propolis almost concomitantly by two independent publications. -

India Fights to Get Rosewood Delisted from CITES

India Fights to Get Rosewood Delisted from CITES drishtiias.com/printpdf/india-fights-to-get-rosewood-delisted-from-cites India, with the help of Bangladesh and Nepal, is trying to de-list ‘Dalbergia sissoo’, from the list of threatened varieties in order to protect the livelihood of handicraft manufacturers and farmers in the Sub-continent. Dalbergia sissoo is commonly known Rosewood, Shisham and is a medium to large deciduous tree, native to India, with a slight crown. Distribution: It is native to the foothills of the Himalayas. It is primarily found growing along river banks below 900 metres (3,000 ft) elevation, but can range naturally up to 1,300 m (4,300 ft). The temperature in its native range averages 10–40 °C (50–104 °F), but varies from just below freezing to nearly 50 °C (122 °F). It can withstand average annual rainfall up to 2,000 millimetres (79 in) and droughts of 3–4 months. Soils range from pure sand and gravel to rich alluvium of river banks; shisham can grow in slightly saline soils. Use: It is used as firewood, timber, poles, posts, tool handles, fodder, erosion control and as a windbreak. Oil is extracted from the seed and tannin from the bark. It is best known internationally as a premier timber species of the rosewood genus. However, Shisham is also an important fuel wood, shade, and shelter. With its multiple products, tolerance of light frosts and long dry seasons, this species deserves greater consideration for tree farming, reforestation and agroforestry applications. After teak, it is the most important cultivated timber tree in India, planted on roadsides, and as a shade tree for tea plantations. -

Rosewood) to CITES Appendix II.2 the New Listings Entered Into Force on January 2, 2017

Original language: English CoP18 Inf. 50 (English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Eighteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Geneva (Switzerland), 17-28 August 2019 IMPLEMENTING CITES ROSEWOOD SPECIES LISTINGS: A DIAGNOSTIC GUIDE FOR ROSEWOOD RANGE STATES This document has been submitted by the United States of America at the request of the World Resources Institute in relation to agenda item 74.* * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. CoP18 Inf. 50 – p. 1 Draft for Comment August 2019 Implementing CITES Rosewood Species Listings A Diagnostic Guide for Rosewood Range States Charles Victor Barber Karen Winfield DRAFT August 2019 Corresponding Author: Charles Barber [email protected] Draft for Comment August 2019 INTRODUCTION The 17th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP-17) to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), held in South Africa during September- October 2016, marked a turning point in CITES’ treatment of timber species. While a number of tree species had been brought under CITES regulation over the previous decades1, COP-17 saw a marked expansion of CITES timber species listings. The Parties at COP-17 listed the entire Dalbergia genus (some 250 species, including many of the most prized rosewoods), Pterocarpus erinaceous (kosso, a highly-exploited rosewood species from West Africa) and three Guibourtia species (bubinga, another African rosewood) to CITES Appendix II.2 The new listings entered into force on January 2, 2017. -

Dry Forest Trees of Madagascar

The Red List of Dry Forest Trees of Madagascar Emily Beech, Malin Rivers, Sylvie Andriambololonera, Faranirina Lantoarisoa, Helene Ralimanana, Solofo Rakotoarisoa, Aro Vonjy Ramarosandratana, Megan Barstow, Katharine Davies, Ryan Hills, Kate Marfleet & Vololoniaina Jeannoda Published by Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House, 199 Kew Road, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3BW, UK. © 2020 Botanic Gardens Conservation International ISBN-10: 978-1-905164-75-2 ISBN-13: 978-1-905164-75-2 Reproduction of any part of the publication for educational, conservation and other non-profit purposes is authorized without prior permission from the copyright holder, provided that the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. Recommended citation: Beech, E., Rivers, M., Andriambololonera, S., Lantoarisoa, F., Ralimanana, H., Rakotoarisoa, S., Ramarosandratana, A.V., Barstow, M., Davies, K., Hills, BOTANIC GARDENS CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL (BGCI) R., Marfleet, K. and Jeannoda, V. (2020). Red List of is the world’s largest plant conservation network, comprising more than Dry Forest Trees of Madagascar. BGCI. Richmond, UK. 500 botanic gardens in over 100 countries, and provides the secretariat to AUTHORS the IUCN/SSC Global Tree Specialist Group. BGCI was established in 1987 Sylvie Andriambololonera and and is a registered charity with offices in the UK, US, China and Kenya. Faranirina Lantoarisoa: Missouri Botanical Garden Madagascar Program Helene Ralimanana and Solofo Rakotoarisoa: Kew Madagascar Conservation Centre Aro Vonjy Ramarosandratana: University of Antananarivo (Plant Biology and Ecology Department) THE IUCN/SSC GLOBAL TREE SPECIALIST GROUP (GTSG) forms part of the Species Survival Commission’s network of over 7,000 Emily Beech, Megan Barstow, Katharine Davies, Ryan Hills, Kate Marfleet and Malin Rivers: BGCI volunteers working to stop the loss of plants, animals and their habitats. -

Ecology, and Population Status of Dalbergia Latifolia from Indonesia

A REVIEW ON TAXONOMY, BIOLOGY, ECOLOGY, AND POPULATION STATUS OF DALBERGIA LATIFOLIA FROM INDONESIA K U S U M A D E W I S R I Y U L I T A , R I Z K I A R Y F A M B A Y U N , T I T I E K S E T Y A W A T I , A T O K S U B I A K T O , D W I S E T Y O R I N I , H E N T I H E N D A L A S T U T I , A N D B A Y U A R I E F P R A T A M A A review on Taxonomy, Biology, Ecology, and Population Status of Dalbergia latifolia from Indonesia Kusumadewi Sri Yulita, Rizki Ary Fambayun, Titiek Setyawati, Atok Subiakto, Dwi Setyo Rini, Henti Hendalastuti, and Bayu Arief Pratama Introduction Dalbergia latifolia Roxb. (Fabaceae) is known as sonokeling in Indonesia. The species may not native to Indonesia but have been naturalised in several islands of Indonesia since it was introduced from India (Sunarno 1996; Maridi et al. 2014; Arisoesilaningsih and Soejono 2015; Adema et al. 2016;). The species has beautiful dark purple heartwood (Figure 1). The wood is extracted to be manufactured mainly for musical instrument (Karlinasari et al. 2010). At present, the species have been cultivated mainly in agroforestry (Hani and Suryanto 2014; Mulyana et al., 2017). The main distribution of species in Indonesia including Java and West Nusa Tenggara (Djajanti 2006; Maridi et al. -

Dalbergia Sissoo Dc

IJRPC 2013, 3(2) Sudhakar et al. ISSN: 22312781 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN PHARMACY AND CHEMISTRY Available online at www.ijrpc.com Review Article DALBERGIA SISSOO DC. - AN IMPORTANT MEDICINAL PLANT M. Bharath, E. Laxmi Rama Tulasi, K. Sudhakar* and M. Chinna Eswaraiah Department of Pharmacognosy, Anurag Pharmacy College, Ananthagiri (V) - 508206, Kodad (M), Nalgonda (Dt), Andhra Pradesh, India. ABSTRACT Nature has been a good source of medicinal agents for thousands of years and an impressive number of modern drugs have been isolated from natural sources, many based on their use in traditional medicine. Various medicinal plants have been used for years in daily life to treat diseases all over the world. The present study reveals the medicinal values of Dalbergia sissoo DC. (Fabaceae). In this communication, we reviewed the Phytochemistry and its applications in the treatment of various ailments. The genus consists of 300 species among which 25 species occur in India. The generic name Dalbergia honors the Swedish brothers Nils and Carl Dalberg, who lived in the 18th century. The plant is used in treatment of leprosy, jaundice, gonorrhea and syphilis etc. Keywords: Dalbergia sissoo DC. Fabaceae, Phytochemistry, Jaundice, Leprosy. INTRODUCTION freezing to nearly 50 °C (122 °F). It can Herbal drugs are used in traditional methods of withstand average annual rainfall of 500 to 2,000 treating the diseases worldwide. Several types mm (79 in) and droughts of 3–4 months. Soils of medicinal plants are existing in the nature and range from pure sand and gravel to rich alluvium are effective in treating different type of of river banks, sissoo can grow in slightly saline diseases.1 Herbal medicine is a triumph of soils. -

Exempted Trees List

Prohibited Plants List The following plants should not be planted within the City of North Miami. They do not require a Tree Removal Permit to remove. City of North Miami, 2017 Comprehensive List of Exempted Species Pg. 1/4 Scientific Name Common Name Abrus precatorius Rosary pea Acacia auriculiformis Earleaf acacia Adenanthera pavonina Red beadtree, red sandalwood Aibezzia lebbek woman's tongue Albizia lebbeck Woman's tongue, lebbeck tree, siris tree Antigonon leptopus Coral vine, queen's jewels Araucaria heterophylla Norfolk Island pine Ardisia crenata Scratchthroat, coral ardisia Ardisia elliptica Shoebutton, shoebutton ardisia Bauhinia purpurea orchid tree; Butterfly Tree; Mountain Ebony Bauhinia variegate orchid tree; Mountain Ebony; Buddhist Bauhinia Bischofia javanica bishop wood Brassia actino-phylla schefflera Calophyllum antillanum =C inophyllum Casuarina equisetifolia Australian pine Casuarina spp. Australian pine, sheoak, beefwood Catharanthus roseus Madagascar periwinkle, Rose Periwinkle; Old Maid; Cape Periwinkle Cestrum diurnum Dayflowering jessamine, day blooming jasmine, day jessamine Cinnamomum camphora Camphortree, camphor tree Colubrina asiatica Asian nakedwood, leatherleaf, latherleaf Cupaniopsis anacardioides Carrotwood Dalbergia sissoo Indian rosewood, sissoo Dioscorea alata White yam, winged yam Pg. 2/4 Comprehensive List of Exempted Species Scientific Name Common Name Dioscorea bulbifera Air potato, bitter yam, potato vine Eichhornia crassipes Common water-hyacinth, water-hyacinth Epipremnum pinnatum pothos; Taro -

Wood Anatomical Traits of the Araucaria Forest, Southern Brazil Anatomía De La Madera Del Bosque De Araucaria, Sur De Brasil

BOSQUE 37(1): 21-31, 2016 DOI: 10.4067/S0717-92002016000100003 ARTÍCULOS Wood anatomical traits of the Araucaria Forest, Southern Brazil Anatomía de la madera del bosque de araucaria, sur de Brasil Patricia Soffiatti a*, Maria Regina Torres Boeger a, Silvana Nisgoski b, Felipe Kauai a *Corresponding Author: a Universidade Federal do Paraná, Departamento de Botânica, CxP 19031, CEP81531-990, Curitiba, Brazil, phone: +55 41 3361-1631, [email protected] b Universidade Federal do Paraná, Departamento de Engenharia Florestal, Curitiba, Brazil. SUMMARY The goal of the present study was to find a pattern regarding wood anatomical features for the Araucaria Forest. For that, we studied the wood anatomy of 17 tree species characteristics of this forest formation of Southern Brazil. The species were selected based on the amplified importance value. Wood samples of three individuals per species were collected and prepared according to standard wood anatomical techniques. Most of the species can be grouped according to the presence of the following features: visible growth rings, diffuse porosity, absence of any typical vessel arrangement, simple perforation plate, simple to diminute bordered pits in fibers, little axial parenchyma, heterogeneous rays. The Grouping Analysis of qualitative and quantitative characters groups the species together, but two are distinct from the others: Cinnamodendron dinisii and Roupala montana. Principal Component Analysis explained 69 % of the total variance, influenced by rays height and width, vessel element and fiber length, separating Cinnamodendron dinisii and Roupala montana from the others. Results corroborated ecological wood anatomical patterns observed for other species in other tropical and subtropical vegetation formations occurring in higher altitudes and latitudes, where the species can be characterized by the presence of visible growth rings, predominantly solitary vessels, simple perforation plates and little axial parenchyma. -

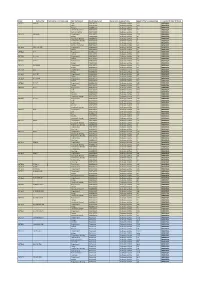

List of Instruments Affected by CITES II

Brand Itemnumber Itemnumber incl.