Conflict in Tragedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American Postdramatic Television Series: the Art of Poetry and the Composition of Chaos (How to Understand the Script of the Best American Television Series)”

RLCS, Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 72 – Pages 500 to 520 Funded Research | DOI: 10.4185/RLCS, 72-2017-1176| ISSN 1138-5820 | Year 2017 How to cite this article in bibliographies / References MA Orosa, M López-Golán , C Márquez-Domínguez, YT Ramos-Gil (2017): “The American postdramatic television series: the art of poetry and the composition of chaos (How to understand the script of the best American television series)”. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 72, pp. 500 to 520. http://www.revistalatinacs.org/072paper/1176/26en.html DOI: 10.4185/RLCS-2017-1176 The American postdramatic television series: the art of poetry and the composition of chaos How to understand the script of the best American television series Miguel Ángel Orosa [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – [email protected] Mónica López Golán [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – moLó[email protected] Carmelo Márquez-Domínguez [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – camarquez @pucesi.edu.ec Yalitza Therly Ramos Gil [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – [email protected] Abstract Introduction: The magnitude of the (post)dramatic changes that have been taking place in American audiovisual fiction only happen every several hundred years. The goal of this research work is to highlight the features of the change occurring within the organisational (post)dramatic realm of American serial television. -

Myth Y La Magia: Magical Realism and the Modernism of Latin America

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2015 Myth y la magia: Magical Realism and the Modernism of Latin America Hannah R. Widdifield University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, and the Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons Recommended Citation Widdifield, Hannah R., "Myth y la magia: Magical Realism and the Modernism of Latin America. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2015. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/3421 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Hannah R. Widdifield entitled "Myth y la magia: Magical Realism and the Modernism of Latin America." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Lisi M. Schoenbach, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Allen R. Dunn, Urmila S. Seshagiri Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Myth y la magia: Magical Realism and the Modernism of Latin America A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Hannah R. -

A Computational Model of Narrative Generation for Suspense

A Computational Model of Narrative Generation for Suspense Yun-Gyung Cheong and R. Michael Young Liquid Narrative Group Department of Computer Science North Carolina State University Raleigh, NC 27695 [email protected], [email protected] Abstract that is leading to a significant outcome, b) intervening Although suspense contributes significantly to the events, and c) the outcome. enjoyment of a narrative by its readers, its role in dynamic Our approach attempts to manipulate the level of story generation systems has been largely ignored. This suspense experienced by a story’s reader by elaborating on paper presents Suspenser, a computational model of the story structure — making decisions regarding what narrative generation that takes as input a given story world story elements to tell and when to tell them — that can and constructs a narrative structure intended to evoke the influence the reader’s narrative comprehension process. desirable level of suspense from the reader at a specific To this end, we make use of a computational model of that moment in the story. Our system is based on the concepts comprehension process based on evidence from previous that a) the reader’s suspense level is affected by the number psychological studies (Brewer, 1996; Gerrig and Bernardo, of solutions available to the problems faced by a narrative’s protagonists, and b) story structure can influence the 1994; Comisky and Bryant, 1982). To generate suspenseful reader’s narrative comprehension process. We use the stories, we set out a basic approach built on a tripartite Longbow planning algorithm to approximate the reader’s model, adapted from narrative theory, that involves the planning-related reasoning in order to estimate the number following elements: the fabula, the sjuzhet, and the of anticipated solutions that the reader builds at a specific discourse (Rimmon-Kenan; 2002). -

An Analysis of the Magical Beauty in One Hundred Years of Solitude and Its Influence on Chinese Literature

Frontiers in Educational Research ISSN 2522-6398 Vol. 4, Issue 7: 56-61, DOI: 10.25236/FER.2021.040711 An Analysis of the Magical Beauty in One Hundred Years of Solitude and Its Influence on Chinese Literature Hui Han School of Foreign Language, Hubei University of Arts and Science, Xiangyang City, China Abstract: One Hundred Years of Solitude is the most representative work of magic realism in the literature created by Colombian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and it is a dazzling pearl in magic realism literature. Marquez used magical techniques to describe the tortuous and legendary experiences of several generations of the Buendia family in the small town. Through the refraction of the magical realm, it indirectly reflects the history of Latin America and the cruel real life, and expresses people's desire for independence and stability. Compared with other Western literary schools, magic realism is one of the literary schools that have a profound influence on the development of modern and contemporary Chinese literature. This article mainly analyzes the magical beauty of One Hundred Years of Solitude and its influence on Chinese literature through magic realism. Keywords: magic realism, One Hundred Years of Solitude, root-seeking literature 1. Introduction Magic realism originated in Latin America. From the 1950s to the 1970s, Latin American literature had an amazing and explosive breakthrough. A series of masterpieces came out, and various literary schools came into being. Among the numerous literary schools, the most important is undoubtedly magic realism, which occupies a very important position in the contemporary world literary world. The publication of "One Hundred Years of Solitude" brought the literary creation of magic realism to the peak and caused an explosive sensation in the world literary world. -

Grade 4 Narrative Writing Guide

Grade 4 Narrative Writing Guide Student Pages for Print or Projection SECTION 4: Suspense www.empoweringwriters.com 1-866-285-3516 Student Page Name____________________________________________ FIND THE SUSPENSE! Authors can build suspense by raising story questions to make you wonder or worry. They can use word referents in order to hint at, rather than name, a revelation. Read each suspenseful segment. Underline story questions in red. Underline the use of word referents in blue. 1. Robert climbed the steps to the old deserted house. Everyone said it was haunted, but could that really be true? He didn’t believe that things like ghosts or spirits actually existed. Robert took a deep breath and put his hand on the doorknob. He thought about the dare, and paused. Would he have the guts to go inside and see for himself? 2. Maria knew she should have worn her hiking boots and heavy socks - that sandals were not safe in this environment. She stepped carefully over the rocks and cautiously through the tall grass. She felt a sense of danger before she actually saw it. She heard a swishing sound and saw the grass in front of her separate. The rattling sound that came next stopped her short. What was hiding in the grass, she wondered? Its beady eyes glinted in the light and its tongue flicked. But when the the tip of the deadly creature’s tail, raised up, angrily vibrating its poisonous warning was the most terrifying thing Maria had ever laid eyes on. 3. Ben held the small gift-wrapped box in his hand for a moment. -

ELEMENTS of FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms That Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction

Dr. Hallett ELEMENTS OF FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms that Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction” is defined as any imaginative re-creation of life in prose narrative form. All fiction is a falsehood of sorts because it relates events that never actually happened to people (characters) who never existed, at least not in the manner portrayed in the stories. However, fiction writers aim at creating “legitimate untruths,” since they seek to demonstrate meaningful insights into the human condition. Therefore, fiction is “untrue” in the absolute sense, but true in the universal sense. Critical Thinking – analysis of any work of literature – requires a thorough investigation of the “who, where, when, what, why, etc.” of the work. Narrator / Narrative Voice Guiding Question: Who is telling the story? …What is the … Narrative Point of View is the perspective from which the events in the story are observed and recounted. To determine the point of view, identify who is telling the story, that is, the viewer through whose eyes the readers see the action (the narrator). Consider these aspects: A. Pronoun p-o-v: First (I, We)/Second (You)/Third Person narrator (He, She, It, They] B. Narrator’s degree of Omniscience [Full, Limited, Partial, None]* C. Narrator’s degree of Objectivity [Complete, None, Some (Editorial?), Ironic]* D. Narrator’s “Un/Reliability” * The Third Person (therefore, apparently Objective) Totally Omniscient (fly-on-the-wall) Narrator is the classic narrative point of view through which a disembodied narrative voice (not that of a participant in the events) knows everything (omniscient) recounts the events, introduces the characters, reports dialogue and thoughts, and all details. -

9. List of Film Genres and Sub-Genres PDF HANDOUT

9. List of film genres and sub-genres PDF HANDOUT The following list of film genres and sub-genres has been adapted from “Film Sub-Genres Types (and Hybrids)” written by Tim Dirks29. Genre Film sub-genres types and hybrids Action or adventure • Action or Adventure Comedy • Literature/Folklore Adventure • Action/Adventure Drama Heroes • Alien Invasion • Martial Arts Action (Kung-Fu) • Animal • Man- or Woman-In-Peril • Biker • Man vs. Nature • Blaxploitation • Mountain • Blockbusters • Period Action Films • Buddy • Political Conspiracies, Thrillers • Buddy Cops (or Odd Couple) • Poliziotteschi (Italian) • Caper • Prison • Chase Films or Thrillers • Psychological Thriller • Comic-Book Action • Quest • Confined Space Action • Rape and Revenge Films • Conspiracy Thriller (Paranoid • Road Thriller) • Romantic Adventures • Cop Action • Sci-Fi Action/Adventure • Costume Adventures • Samurai • Crime Films • Sea Adventures • Desert Epics • Searches/Expeditions for Lost • Disaster or Doomsday Continents • Epic Adventure Films • Serialized films • Erotic Thrillers • Space Adventures • Escape • Sports—Action • Espionage • Spy • Exploitation (ie Nunsploitation, • Straight Action/Conflict Naziploitation • Super-Heroes • Family-oriented Adventure • Surfing or Surf Films • Fantasy Adventure • Survival • Futuristic • Swashbuckler • Girls With Guns • Sword and Sorcery (or “Sword and • Guy Films Sandal”) • Heist—Caper Films • (Action) Suspense Thrillers • Heroic Bloodshed Films • Techno-Thrillers • Historical Spectacles • Treasure Hunts • Hong Kong • Undercover -

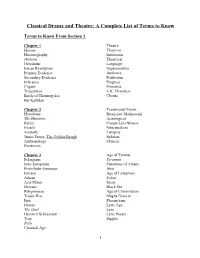

A Complete List of Terms to Know

Classical Drama and Theatre: A Complete List of Terms to Know Terms to Know From Section 1: Chapter 1 Theatre History Theatron Historiography Institution Historia Theatrical Herodotus Language Ionian Revolution Impersonation Primary Evidence Audience Secondary Evidence Positivism Inference Progress Cogent Primitive Tripartition E.K. Chambers Battle of Thermopylae Chorus Ibn Kahldun Chapter 2 Transitional Forms Herodotus Bronislaw Malinowski The Histories Aetiological Relics Claude Levi-Strauss Fossils Structuralism Aristotle Lumpers James Frazer, The Golden Bough Splitters Anthropology Mimetic Positivism Chapter 3 Age of Tyrants Pelasgians Tyrannos Indo-Europeans Pisistratus of Athens Proto-Indo-European Attic Ionians Age of Lawgivers Athens Solon Asia Minor Sicily Dorians Black Sea Peloponnese Age of Colonization Trojan War Magna Graecia Epic Phoenicians Homer Lyric Age The Iliad Lyre Heinrich Schliemann Lyric Poetry Troy Sappho Polis Classical Age 1 Chapter 4.1 City Dionysia Thespis Ecstasy Tragoidia "Nothing To Do With Dionysus" Aristotle Year-Spirit The Poetics William Ridgeway Dithyramb Tomb-Theory Bacchylides Hero-Cult Theory Trialogue Gerald Else Dionysus Chapter 4.2 Niches Paleontologists Fitness Charles Darwin Nautilus/Nautiloids Transitional Forms Cultural Darwinism Gradualism Pisistratus Steven Jay Gould City Dionysia Punctuated Equilibrium Annual Trading Season Terms to Know From Section 2: Chapter 5 Sparta Pisistratus Peloponnesian War Athens Post-Classical Age Classical Age Macedon(ia) Persian Wars Barbarian Pericles Philip -

I Am Rooted, but I Flow': Virginia Woolf and 20Th Century Thought Emily Lauren Hanna Scripps College

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Keck Graduate Institute Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2012 'I Am Rooted, But I Flow': Virginia Woolf and 20th Century Thought Emily Lauren Hanna Scripps College Recommended Citation Hanna, Emily Lauren, "'I Am Rooted, But I Flow': Virginia Woolf and 20th Century Thought" (2012). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 97. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/97 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ‘I AM ROOTED, BUT I FLOW’: VIRGINIA WOOLF AND 20 TH CENTURY THOUGHT by EMILY LAUREN HANNA SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR MATZ PROFESSOR GREENE APRIL 20, 2012 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT It is a pleasure to thank those who made this thesis possible, including Professors Matz, Greene, Peavoy, and Wachtel, whose inspiration and guidance enabled me to develop an appreciation and understanding of the work of Virginia Woolf. I would also like to thank my friends, and above all, my family who helped foster my love of literature, and supported me from the initial stages of my project through its completion. Emily Hanna 2 Table of Contents Introduction 4 Chapter 1 – Conceptual Framework 7 Chapter 2 – Mrs. Dalloway 22 Chapter 3 – To the Lighthouse 34 Chapter 4 – The Waves 50 Conclusion 63 Works Cited 65 3 Introduction If life has a base that it stands upon, if it is a bowl that one fills and fills and fills – then my bowl without a doubt stands upon this memory. -

1 in Defense of Croesus, Or Suspense As an Aesthetic

AISTHE, nº 3, 2008 ISSN 1981-7827 Konstan, David In defense of Croesus, or Suspense as an aesthetic emotion IN DEFENSE OF CROESUS, OR SUSPENSE AS AN AESTHETIC EMOTION David Konstan University of Brown Abstract: Suspense is perhaps unique in being an emotion that responds specifically to narrative: without a story, with beginning, middle, and end, there is no suspense. Some have argued the reverse as well: it is not a story if it does not produce suspense (Brewer and Lichtenstein 1981). Suspense, which is compounded of hope and fear (Ortony, Clore, and Collins 1988), anticipates a conclusion: hence its connection with narrative closure. Paradoxically, there is suspense even where the outcome of a story is known (Carroll 1996). Suspense thus provides rich material for the poetics of emotion, yet it has rarely been examined in connection with classical literature and emotion theory. Keywords: Suspense, Emotion, Narrative, Resumo : O suspense é talvez ímpar enquanto uma emoção que corresponde especificamente à narrativa: sem história, sem começo meio e fim, não há suspense (Brewer and Lichtenstein 1981). O suspense, que é composto de expectativa e medo (Ortony, Clore, and Collins 1988), antecipa uma conclusão: daí sua conexão com o desfecho da narrativa. Paradoxalmente, há suspense mesmo se o desenlace de uma história é conhecido (Carroll 1996). O suspense, portanto, provê matéria preciosa para a poética da emoção, ainda que raramente tenha sido examinado em conexão com a literatura clássica e a teoria da emoção. Palavras-chave: Suspense, Emoção, Narrativa "There ought to be behind the door of every happy, contented man someone standing with a hammer continually reminding him with a tap that there are unhappy people; that however happy he may be, life will show him her laws sooner or later, trouble will come for him."1 Suspense is a particularly relevant sentiment in connection with the "poetics of emotions," since it would seem to bear a special relationship to narrative -- and narrative is certainly at the heart of any conception of poetics. -

Suspense.Pdf

Suspense Can you think of a novel that you have read into the wee hours of the night because you simply couldn’t put it down? That is the power of suspense!! The reader is left hanging and needs to read on in order to figure out what happens to the character! Building suspense into writing allows the author to give the reader a hint as to what is to come! The author shares a little bit at a time allowing the reader to wonder or worry what will happen next in the story. This sense of anticipation hooks the reader and moves a story forward into the main event. In grade 5, students focus on three main techniques in order to learn the art of adding suspense to writing! Story Questions: One way we teach suspense is through story questions. The simplest way to do that is to have the main character raise a story question like; What in the world is happening to my bike? What was that sound in the woods? Did I really just see what I think I did? Word Referents: Another technique to teach suspense is word referents. A word referent is a description of a character or an object without naming it. For instance: The creature stood on its hind legs and growled. It lumbered closer and closer to me. I felt its hot breath on my face and was frozen with fear. The fish eater reached out a giant paw and that was when I turned and ran. Notice the author did not have to tell you it was a bear, but rather was able to describe it without naming it thereby creating a sense of anticipation in the story! The Magic of Three: The final technique we use to teach suspense is The Magic of Three. -

Affective Disposition Theory in Suspense: Elucidating the Roles of Morality and Character Liking in Creating Suspenseful Affect

Affective Disposition Theory in Suspense: Elucidating the Roles of Morality and Character Liking in Creating Suspenseful Affect Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sarah Brookes, M.A. Graduate Program in Communication The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Emily Moyer-Gusé, Advisor David R. Ewoldsen Silvia Knobloch-Westerwick Daniel G. McDonald Copyright by Sarah Brookes 2013 Abstract According to affective disposition theory, our enjoyment of narratives is a function of our feelings toward characters and perceived justness of the outcomes they encounter. Research on suspense has demonstrated that liking characters leads to greater suspense, and that morally just outcomes are associated with greater enjoyment of the narrative. However, additional factors may be relevant in this context. More specifically, perceived threat may act as a complement to character liking, and timing of narrative events may alter the impact of morality. Two studies were conducted in an effort to both complement and challenge affective disposition theory. Study 1 revealed that greater character liking, self-threat, and character-threat are all associated with more suspense and, through excitation transfer, more enjoyment. The first study also found threat to be positively associated with identification, liking, and transportation. Study 2 demonstrated that valence of a midpoint narrative outcome does not necessarily matter for suspense, in that a protagonist’s extreme success and extreme failure in the middle of the narrative were associated with roughly the same amount of suspense. Implications for affective disposition theory are discussed. ii Acknowledgements Thanks are due to my entire committee for helping shape and focus my dissertation.