A Social Assessment of Poverty in Latvia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LONG-TERM CHANGES in the WATER TEMPERATURE of RIVERS in LATVIA Inese Latkovska1,2 # and Elga Apsîte1

PROCEEDINGS OF THE LATVIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES. Section B, Vol. 70 (2016), No. 2 (701), pp. 78–87. DOI: 10.1515/prolas-2016-0013 LONG-TERM CHANGES IN THE WATER TEMPERATURE OF RIVERS IN LATVIA Inese Latkovska1,2 # and Elga Apsîte1 1 Faculty of Geography and Earth Sciences, University of Latvia, Jelgavas iela 1, Rîga LV-1004, LATVIA, e-mail: [email protected] 2 Latvian Environment, Geology, and Meteorology Centre, Maskavas iela 165, Rîga LV-1019, LATVIA # Corresponding author Communicated by Mâris Kïaviòð The study describes the trends of monthly mean water temperature (from May to October) and the annual maximum water temperature of the rivers in Latvia during the time period from 1945 to 2000. The results demonstrated that the mean water temperatures during the monitoring period from May to October were higher in the largest rivers (from 13.6 oC to 16.1 oC) compared to those in the smallest rivers (from 11.5 oC to 15.7 oC). Similar patterns were seen for the maxi- mum water temperature: in large rivers from 22.9 oC to 25.7 oC, and in small rivers from 20.8 oC to 25.8 oC. Generally, lower water temperatures occurred in rivers with a high groundwater inflow rate, for example, in rivers of the Gauja basin, in particular, in the Amata River. Mann-Kendall test results demonstrated that during the monitoring period from May to October, mean water tem- peratures had a positive trend. However, the annual maximum temperature had a negative trend. Key words: water temperature, long-term changes, river, Latvia. -

The Baltic Republics

FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES THE BALTIC REPUBLICS A Strategic Survey Erkki Nordberg National Defence College Helsinki 1994 Finnish Defence Studies is published under the auspices of the National Defence College, and the contributions reflect the fields of research and teaching of the College. Finnish Defence Studies will occasionally feature documentation on Finnish Security Policy. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily imply endorsement by the National Defence College. Editor: Kalevi Ruhala Editorial Assistant: Matti Hongisto Editorial Board: Chairman Prof. Mikko Viitasalo, National Defence College Dr. Pauli Järvenpää, Ministry of Defence Col. Antti Numminen, General Headquarters Dr., Lt.Col. (ret.) Pekka Visuri, Finnish Institute of International Affairs Dr. Matti Vuorio, Scientific Committee for National Defence Published by NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE P.O. Box 266 FIN - 00171 Helsinki FINLAND FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES 6 THE BALTIC REPUBLICS A Strategic Survey Erkki Nordberg National Defence College Helsinki 1992 ISBN 951-25-0709-9 ISSN 0788-5571 © Copyright 1994: National Defence College All rights reserved Painatuskeskus Oy Pasilan pikapaino Helsinki 1994 Preface Until the end of the First World War, the Baltic region was understood as a geographical area comprising the coastal strip of the Baltic Sea from the Gulf of Danzig to the Gulf of Finland. In the years between the two World Wars the concept became more political in nature: after Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania obtained their independence in 1918 the region gradually became understood as the geographical entity made up of these three republics. Although the Baltic region is geographically fairly homogeneous, each of the newly restored republics possesses unique geographical and strategic features. -

Health Systems in Transition

61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 1 03/03/2020 09:55 Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Vol. Health Systems in Transition Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Health Systems in Transition: in Transition: Health Systems C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Latvia Latvia Health system review Daiga Behmane Alina Dudele Anita Villerusa Janis Misins The Observatory is a partnership, hosted by WHO/Europe, which includes other international organizations (the European Commission, the World Bank); national and regional governments (Austria, Belgium, Finland, Kristine Klavina Ireland, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the Veneto Region of Italy); other health system organizations (the French National Union of Health Insurance Funds (UNCAM), the Dzintars Mozgis Health Foundation); and academia (the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and the Giada Scarpetti London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM)). The Observatory has a secretariat in Brussels and it has hubs in London at LSE and LSHTM) and at the Berlin University of Technology. HiTs are in-depth profiles of health systems and policies, produced using a standardized approach that allows comparison across countries. They provide facts, figures and analysis and highlight reform initiatives in progress. Print ISSN 1817-6119 Web ISSN 1817-6127 61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 2 03/03/2020 09:55 Giada Scarpetti (Editor), and Ewout van Ginneken (Series editor) were responsible for this HiT Editorial Board Series editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Josep Figueras, European -

Water Tourism D

5 POTTERY WORKSHOP OF VALDIS PAULINS CATERING SERVICES Hello, traveller! Address: Dumu Street 8, Kraslava, Kraslava municipality, Latvia 13 JAUNDOME ENVORONMENTAL EDUCATION CENTRE AND EXHIBITION HALL 21 MUSIC WORKSHOP “BALTHARMONIA” Mob.: +371 29128695 DINING HALL „ DAUGAVA” Address: Novomisli, Ezernieki rural territory, Dagda municipality, Latvia Address: "Bikava 2a", Gaigalava, Gaigalava rural territory, Rezekne municipality, Latvia CAFE “PIE ČERVONKAS PILS” This is a guide-book that will help you to experience an exciting trip along The Green Routes E-mail: [email protected] Address: Rigas Street 28, Kraslava, Mob.: +371 25960309 Phone: +371 28728790, + 371 26593441 Address: Cervonka-1, Vecsaliena rural territory, of the border areas of Latvia, Lithuania and Belarus. Routes leading to specially protected nature Website: http://www.visitkraslava.com/ Kraslavas municipality, Latvia E - mail: [email protected] E - mail: [email protected] Daugavpils municipality, Latvia areas under the state care are called “green” ones. These routes are “green” because providers of GPS: X:697648, Y:199786 / 55° 54' 10.30", 27° 9'42.27" Phone: +371 65622634, Mob.: +371 29112899 Website: www.visitdagda.com Website: http://www.baltharmonia.lv Mob.: +371 29726105 tourism service take care of accessibility of environment for people with disabilities. The workshop is around on the territory of the protected landscape Fax: +371 65622266 GPS: X:723253, Y:227872 / 56° 8' 36.72", 27° 35'88" GPS: X:687623, Y:291964 / 56° 44' 1.98", 27° 4'2.23" GPS: X: 673571, Y: 189832 / 55° 49’ 22.13’’, 26° 46’ 14.74’’ You are welcome at the places, where you will get acquainted with the values of the nature area „Augšdaugava”. -

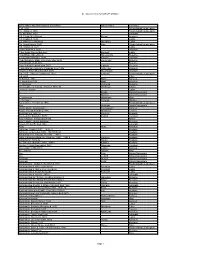

All Latvia Cemetery List-Final-By First Name#2

All Latvia Cemetery List by First Name Given Name and Grave Marker Information Family Name Cemetery ? d. 1904 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? b. Itshak d. 1863 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? b. Abraham 1900 Jekabpils ? B. Chaim Meir Potash Potash Kraslava ? B. Eliazar d. 5632 Ludza ? B. Haim Zev Shuvakov Shuvakov Ludza ? b. Itshak Katz d. 1850 Katz Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? B. Shalom d. 5634 Ludza ? bar Abraham d. 5662 Varaklani ? Bar David Shmuel Bombart Bombart Ludza ? bar Efraim Shmethovits Shmethovits Rezekne ? Bar Haim Kafman d. 5680 Kafman Varaklani ? bar Menahem Mane Zomerman died 5693 Zomerman Rezekne ? bar Menahem Mendel Rezekne ? bar Yehuda Lapinski died 5677 Lapinski Rezekne ? Bat Abraham Telts wife of Lipman Liver 1906 Telts Liver Kraslava ? bat ben Tzion Shvarbrand d. 5674 Shvarbrand Varaklani ? d. 1875 Pinchus Judelson d. 1923 Judelson Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? d. 5608 Pilten ?? Bloch d. 1931 Bloch Karsava ?? Nagli died 5679 Nagli Rezekne ?? Vechman Vechman Rezekne ??? daughter of Yehuda Hirshman 7870-30 Hirshman Saldus ?meret b. Eliazar Ludza A. Broido Dvinsk/Daugavpils A. Blostein Dvinsk/Daugavpils A. Hirschman Hirschman Rīga A. Perlman Perlman Windau Aaron Zev b. Yehiskiel d. 1910 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava Aba Ostrinsky Dvinsk/Daugavpils Aba b. Moshe Skorobogat? Skorobogat? Karsava Aba b. Yehuda Hirshberg 1916 Hirshberg Tukums Aba Koblentz 1891-30 Koblentz Krustpils Aba Leib bar Ziskind d. 5678 Ziskind Varaklani Aba Yehuda b. Shrago died 1880 Riebini Aba Yehuda Leib bar Abraham Rezekne Abarihel?? bar Eli died 1866 Jekabpils Abay Abay Kraslava Abba bar Jehuda 1925? 1890-22 Krustpils Abba bar Jehuda died 1925 film#1890-23 Krustpils Abba Haim ben Yehuda Leib 1885 1886-1 Krustpils Abba Jehuda bar Mordehaj Hakohen 1899? 1890-9 hacohen Krustpils Abba Ravdin 1889-32 Ravdin Krustpils Abe bar Josef Kaitzner 1960 1883-1 Kaitzner Krustpils Abe bat Feivish Shpungin d. -

The Military Heritage and Environment of Kurzeme

SELFDRIVE THE MILITARY HERITAGE AND ENVIRONMENT OF KURZEME The NATURA 2000 system was established by European Union member states to protect a large series of environmental territories. In Latvia’s case, the system includes territories that were protected before it was set up, as well as 122 new territories. Each EU member state establishes its own system of territories, and these are then joined in the central system. NATURA 2000 territories are of European importance and are environmentally protected. Along this route, the most interesting NATURA 2000 territories include the Zvārde Forest Park, the Embūte Nature Park, the Ziemupe Nature Reserve and the Nature Park of the Ancient Abava River Valley. While in these territories, please be gentle with environmental, cultural and historical values. Keep the “interests” of birds in mind when birdwatching. ROUTE During the Soviet era, Latvia was the western border of the USSR, and that made it a strategic location in which lots of military resources were concentrated. During the Soviet occupation, there were more than 1,000 Soviet military units in Latvia, and they controlled some 600 facilities equalling to more than 10% of the territory of the Latvian SSR. In other words, Latvia was behind the Iron Curtain for nearly half a century. Border guard posts, tank bases, aviation bases, military airfields, storage facilities for weapons and munitions (including nuclear missiles), military espionage facilities and other, similar entities were mostly centred on the shore of the Baltic Sea, where there was a special frontier regime. It was just 20 years ago that people were allowed to be on the beach only during sunlight and in very limited areas. -

Competition Schedule

GAME Schedule saturday 3 to sunday 11 july 2021 RIGA & DAUGAVPILS Group A Group B Group C Group D SENEGAL (SEN) PUERTO RICO (PUR) ARGENTINA (ARG) TURKEY (TUR) CANADA (CAN) IRAN (IRI) FRANCE (FRA) MALI (MLI) LITHUANIA (LTU) SERBIA (SRB) KOREA (KOR) AUSTRALIA (AUS) JAPAN (JPN) LATVIA (LAT) SPAIN (ESP) USA (USA) Group Phase SEN - JPN CAN - LTU PUR - LAT IRI - SRB FRA - KOR ARG - ESP TUR - USA MLI - AUS sat (Group A) (Group A) (Group B) (Group B) (Group C) (Group C) (Group D) (Group D) Daugavpils Oly.Centre Daugavpils Oly.Centre Daugavpils Oly.Centre Daugavpils Oly.Centre 03 Riga Olympic Centre Riga Olympic Centre Riga Olympic Centre Riga Olympic Centre 76 - 71 80 - 71 79 - 75 67 - 88 117 - 48 69 - 68 54 - 83 67 - 97 JPN - CAN LTU - SEN LAT - IRI SRB - PUR KOR - ARG ESP - FRA AUS - TUR USA - MLI (Group A) (Group A) (Group B) (Group B) sun (Group C) (Group C) (Group D) (Group D) Daugavpils Oly.Centre Daugavpils Oly.Centre Daugavpils Oly.Centre Daugavpils Oly.Centre 04 Riga Olympic Centre Riga Olympic Centre Riga Olympic Centre Riga Olympic Centre 75 - 100 78 - 73 58 - 48 84 - 64 74 - 112 60 - 59 62 - 64 100 - 52 Monday 5 July - Rest day SEN - CAN LTU - JPN SRB - LAT PUR - IRI KOR - ESP ARG - FRA TUR - MLI AUS - USA (Group A) (Group A) (Group B) (Group B) tue (Group C) (Group C) (Group D) (Group D) Daugavpils Oly.Centre Daugavpils Oly.Centre Daugavpils Oly.Centre Daugavpils Oly.Centre 06 Riga Olympic Centre Riga Olympic Centre Riga Olympic Centre Riga Olympic Centre 56 - 85 95 - 63 71 - 70 68 - 81 48 - 99 52 - 89 58 - 54 66 - 87 FINAL PHASE -

Minutes of the 2Nd Meeting of the Estonian-Latvian Working Group For

Minutes of the 2nd meeting of the Estonian-Latvian Working Group for determing, prioritizing and coordinating the list of road sections for reconstruction in the border area Participants: Mr Vents Armands Krauklis, Chairman of Valka municipality Mr Margus Lepik, Chairman of Valga municipality Mr Andris Zunde, Executive director of Salacgriva municipality Mr Jānis Liberts, Chairman of Ape municipality Mr Artūrs Dukulis, Chairman of Alūksne municipality Mr Enno Kase, Deputy Mayor for Municipal Property and Municipal Maintenance of Valga Municipality Mr Urmas Kuldmaa, Traffic and road specialist of Valga municipality Mr Valdis Barda, Chairman of Aloja municipality Mr Imre Jugomäe, Chairman of Mulgi municipality Mr Guntis Gladkins, Chairman of Rūjiena municipality Mr Gundars Kains, Director of Development Administration of Latvian State Roads Mr Hannes Nagel, Estonian Ministry of Finance AGENDA 1. Overview of the IGC agenda issue as of December 2019 (Information by Estonian Ministry of Finance) 2. Overview of the road section priorities from the national respective authority perspective (Information by the Latvian State Roads) 3. Round table discussion about the cooperation and solution perspectives in regard of covering the prioritized border area gravel road sections with black cover 4. Conclusions and decisions 5. Location and time of 3rd meeting of the working group 1. Overview of the IGC agenda issue as of December 2019 Mr Hannes Nagel of the Estonian Ministry of Finance informed the members of the informal working group about the progress after the November 6 Joint Session of the Estonian and Latvian Intergovernmental Commission. 2. Overview of the road section priorities from the national respective authority perspective Mr Gundars Kains of the Latvian State Roads informed the members of the informal working group about the Latvian national priorities and methodology which is being used to compile the national road renovation list. -

Madona, Varakļāni, MADONA Cesvaines, Ērgļu, Lubānas, Madonas, Varakļānu Novads

Cesvaine, Ērgļi, Lubāna, Madona, Varakļāni, MADONA Cesvaines, Ērgļu, Lubānas, Madonas, Varakļānu novads UZŅĒMUMI KARTES PAŠVALDĪBAS ETENS ETENS Ļ TNIECISKAIS BI TNIECISKAIS Ē P - VI Ī Mājaslapu izstrāde INFORMAT SEO risinājumi Mārketinga koncepti Sociālo tīklu profilu izveide nelieliem uzņēmumiem 2020/21 www.latvijastalrunis.lv 67770577 AKTUĀLAIS UN NOZĪMĪGAIS PORTĀLĀ ZIŅAS AFIŠA KATALOGS KARTE GALERIJAS SLUDINĀJUMI PAŠVALDĪBA Kur zvanīt steidzamos gadījumos?? 2 - 3 Uzziņas un pakalpojumi Pašvaldību informācija 4 - 15 Kartes, ielu saraksti, informācija 16 - 17 Uzņēmējdarbības vide 18 - 19 Alfabētiskais 20 - 28 nozaru saraksts Nozaru daļa 29 - 57 Firmu saraksts pēc to darbības sfēras Advokāti - Bankas 29 - 33 Būvuzraudzība… - Celtniecības… 34 - 35 Ceļu… - Daiļamatniecība 35 - 35 Dzīvnieku… - Ekonomikas… 37 - 37 Ēdināšanas… - Iepakojums… 37 - 39 Izglītība… - Jaunrades… 39 - 40 Juvelierizstrādājumi… - Kafija… 40 - 40 Ķīmiskā… - Labiekārtošana… 42 - 42 Lopkopība - Maize… 43 - 44 Mūzikas - Namu… 46 - 46 Notāri - Parfimērijas… 47 - 47 Putnkopība - Radio… 52 - 53 Rūpniecības… - Sabiedriskais… 53 - 53 Somas… - Tabakas… 54 - 54 Tūrisms… - Ugunsdzēsība… 55 - 55 Ūdensapgāde… - Valsts… 55 - 55 Viesnīcas… - Žalūzijas… 56 - 57 Firmas alfabētiskā secībā Mājaslapu izstrāde A - J 58 - 61 www.latvijastalrunis.lv Firmas alfabētiskā secībā 67770577 K - Z 61 - 68 Uzziņas un pakalpojumi KUR ZVANĪT STEIDZAMOS GADĪJUMOS? UGUNSDZĒSĪBA UN GLĀBŠANA 01, 112 POLICIJA 02, 110, 112 MEDICĪNISKĀ PALĪDZĪBA 03, 112, 113 Medicīniskā palīdzība Avārijas dienesti Madonas slimnīca -

AS "Moda Kapitāls" Annual Report for the Year 2020

AS "Moda Kapitāls” ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2020 prepared in accordance with IFRS us adopted in EU Riga, 29th April, 2021 AS "Moda Kapitāls" Annual report for the year 2020. Prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards as adopted in EU AS "Moda Kapitāls” ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2020 prepared in accordance with IFRS us adopted in EU CONTENT Page General information 3 Management report 4 Statement of management responsibility 5 Financial statements: Statement of comprehensive income 6 Statement of financial position 7 Cash flow statement 8 Statement of changes in equity 9 Notes 10 Independent auditors' report 27 2 AS "Moda Kapitāls” ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2020 prepared in accordance with IFRS us adopted in EU GERNERAL INFORMATION Name of the company Moda Kapitāls Legal status of the company Joint Stock Company Registration number, place and date of registration LV 40003345861, Riga, June 9, 1997 Registered office Ganību dambis 40A-34, Rīga, LV-1005 Shareholders Andris Banders (24.76%), Tvinger SIA (20%), Ilvars Sirmais (16.14%), MK Investīcijas, SIA (14.75%), Verners Skrastiņš (14.05%), Guntars Zvīnis (10.29%) Board Members Guntars Zvīnisas of 23.04.2021 Ilvars Sirmais (till 05.08.2020) Edgars Bilinskis (5.08.2020.-24.11.2020) Marts Zeltiņš (16.12.2020-31.03.2021) Supervisory Board Members Marts Zeltiņš - head of the Council as of 23.04.2021 Andris Banders - deputy of the head of the Council Andris Blaka - member of the Council as of 06.11.2020 Inese Kanneniece - meber of the Council Ilvars Sirmais - member of the Council as of 6.11.2020 Guntars Zvīnis - member of the Council (6.11.2021-22.04.2021) Verners Skrastiņš - head of the Council till 6.11.2020 Diāna Zvīne - member of the Council till 6.11.2020 Ilze Sirmā - member of the Council till 6.11.2020 Financial year from 01.01.2020 to 31.12.2020 Currency used in the financial statements EUR Details of related companies: AUREUM AS, legal address: Peldu Street 6, Liepāja, participation share - 100%. -

Best Baltic Basketball League

BBBL – BEST BALTIC BASKETBALL LEAGUE BBBL is an international basketball tournament for boys & girls aged U10 to U16 (years of birth 2011-2005) BBBL is the biggest and fastest growing regular Youth basketball tournament in Europe • the tournament was founded in 2012 • since season 2019/2020 we have started also girls tournament and renamed league to BEST BALTIC BASKETBALL LEAGUE • season of 2019/2020, BBBL participates 306 teams from 13 countries ABOUT BBBL season 2019/2010 BBBL teams, season 2019/2020, by age groups 60 50 306 teams 40 13 countries 30 20 4300 players 10 0 boys boys boys boys boys boys boys girls U11 girls U12 girls U13 girls U14 U10 U11 U12 U13 U14 U15 U16 BBBL teams by countries, season 2019/2020 MOL UK DEN SWE POL GEO UKR BLR FIN LTU RUS EST LV 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 BBBL STAGE MAP STAGE LOCATIONS LATVIA – Riga, Ozolnieki, Valmiera, Cēsis, Sigulda, Madona, Tukums, Talsi, Ventspils ESTONIA – Tartu, Tallin, Kaarikuu, Viimsi, Saaremaa LITHUANIA – Vilnius, Mazeikiai, Siauliai BELARUS – Minsk RUSSIA – Moscow, Tula FINLAND - Nokia FINAL STAGES : Riga, Valmiera, Cesis, Jelgava, Tartu BBBL TOURNAMENT KEY & FUNNY FACTS season 2019/2020 till covid-19 lockdown • 1851 games / almost all live on YouTube channel • 4300 players / 13 countries • 132 stages / 25 different locations • some teams travel very far away to play in BBBL tournament Krasnoyarsk 5`070 km London 2`317 km number of teams per seasons Tbilisi 2`874 km 350 Odesa 1`519 km 300 250 • besides players and coaches BBBL 200 tournament attracts a lot of other guests 150 /sometimes team brings 40+ person delegation for the bbbl stage/ 100 50 0 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 BBBL TOURNAMENT KEY & FUNNY FACTS • BBBL it`s not just a games, it`s a basketball festival full of joy & positive emotions only youth basketball - Skills challenges tournament where every - 3-point shot contests game is provided with full - Coach challenges FIBA standard live statistics - Coach meetings etc. -

Reģions Vārds Un Uzvārds Mobilais Telefons E-Pasts Darba Pieredze Aglonas Novads Jāzeps Gunārs Ruskulis 29529203 Gunars.Rus

Reģions Vārds un uzvārds Mobilais telefons E-pasts Darba pieredze Radio inženieris specialitātē "Radiotehnika". Ir praktiska pieredze un radošs risinājums nestandarta situācijās. Jāzeps Gunārs Prasmes: pieslēgt TV uztveres ierīces (televizorus, virszemes uztvērējus, Aglonas novads 29529203 [email protected] Ruskulis antenas), konfigurēt programmas, salabot ierīces. Konsultēt par ierīču iegādi, lai garantētu 100 % uztveres iespējas jebkurā vietā vai problemātiskas radio redzamības apstākļos. Aizkraukle Aldis Stepiņš 29837131 [email protected] Satelīttelevīzijas meistars sešus gadus. Aizkraukles novads Aigars Zelčs 26329054 [email protected] Seši gadi satelīttelevīzijas instalācijas. Aizkraukles novads Aldis Stepiņš 29837131 [email protected] Satelīttelevīzijas meistars sešus gadus. Aknīste Aigars Zelčs 26329054 [email protected] Seši gadi satelīttelevīzijas instalācijas. Aknīstes novads Aigars Zelčs 26329054 [email protected] Seši gadi satelīttelevīzijas instalācijas. To vien daru, jau 20 gadus. Viss, kas saistīts ar antenām, gan satelītu, gan Alūksne Andris Liepiņš 29142500 [email protected] virszemes. Alūksnes novads Sandis Tutiņš 28377317 [email protected] Virzemes un satelīttelevīzijas meistars. To vien daru, jau 20 gadus. Viss, kas saistīts ar antenām, gan satelītu, gan Alūksnes novads Andris Liepiņš 29142500 [email protected] virszemes. To vien daru, jau 20 gadus. Viss, kas saistīts ar antenām, gan satelītu, gan Apes novads Andris Liepiņš 29142500 [email protected] virszemes. Apes novads Sandis Tutiņš 28377317 [email protected] Virzemes un satelīttelevīzijas meistars. Vitautas Ādažu novads 29691009 [email protected] Antenu, satelītu, ētera TV instalācijas darbi, TV remonts. Pieredze 25 gadi. Andrijauskas Ādažu novads Artūrs Mihailovs 29273780 [email protected] Satelīttelevīzijas antenu un TV antenu ierīkošana, apkope. Antenu, satelītu, ētera TV, videonovērošanas instalācijas darbi. Pieredze 30 Babītes novads Dmitrijs Čeļadinovs 29510395 [email protected] gadi.