Ri Sheng Chang

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ethnography of the Spring Festival

IMAGINING CHINA IN THE ERA OF GLOBAL CONSUMERISM AND LOCAL CONSCIOUSNESS: MEDIA, MOBILITY, AND THE SPRING FESTIVAL A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Li Ren June 2003 This dissertation entitled IMAGINING CHINA IN THE ERA OF GLOBAL CONSUMERISM AND LOCAL CONSCIOUSNESS: MEDIA, MOBILITY AND THE SPRING FESTIVAL BY LI REN has been approved by the School of Interpersonal Communication and the College of Communication by Arvind Singhal Professor of Interpersonal Communication Timothy A. Simpson Professor of Interpersonal Communication Kathy Krendl Dean, College of Communication REN, LI. Ph.D. June 2003. Interpersonal Communication Imagining China in the Era of Global Consumerism and Local Consciousness: Media, Mobility, and the Spring Festival. (260 pp.) Co-directors of Dissertation: Arvind Singhal and Timothy A. Simpson Using the Spring Festival (the Chinese New Year) as a springboard for fieldwork and discussion, this dissertation explores the rise of electronic media and mobility in contemporary China and their effect on modern Chinese subjectivity, especially, the collective imagination of Chinese people. Informed by cultural studies and ethnographic methods, this research project consisted of 14 in-depth interviews with residents in Chengdu, China, ethnographic participatory observation of local festival activities, and analysis of media events, artifacts, documents, and online communication. The dissertation argues that “cultural China,” an officially-endorsed concept that has transformed a national entity into a borderless cultural entity, is the most conspicuous and powerful public imagery produced and circulated during the 2001 Spring Festival. As a work of collective imagination, cultural China creates a complex and contested space in which the Chinese Party-state, the global consumer culture, and individuals and local communities seek to gain their own ground with various strategies and tactics. -

The Risk Control of Qianzhuang

ISSN 1923-841X [Print] International Business and Management ISSN 1923-8428 [Online] Vol. 16, No. 2, 2018, pp. 38-47 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/10849 www.cscanada.org The Risk Control of Qianzhuang WANG Yanfen[a],* [a]Doctoral student. School of Economics, Central University of Finance was everywhere, and played an important role in the and Economics, Beijing, China. social economy and the modernization of China’s industry *Corresponding author. and commerce.1 Through the financial exchanges between Received 16 September 2018; accepted 22 November 2018 Qianzhuang and Qianzhuang, Qianzhuang and Piaohao Published online 26 December 2018 , Qianzhuang and domestic and foreign banks, a huge financial network was established to communicate Abstract cross-regional trade and foreign trade. As we can see, Qianzhuang is the traditional bank born in China. During Qianzhuang is one of the most representative forms of the late Qing Dynasty to the Republic of China, plenty of business development in China’s financial industry. It historical data proves that Qianzhuang has always been plays an indispensable role in the history of finance and a true financial service provider for Chinese agribusiness even economic history, as well as the transition from and commercial households. The control of deposit and traditional economy to modernization. loan risk in Qianzhuang is a concentrated expression of the The internal organization structure of Qianzhuang localization advantages of Qianzhuang, and it still has a is following the figure 1: eight butlers structure strong enlightenment for the risk control of contemporary . Apart from the manager and manager’s associates, other financial institutions. -

Banks, and Therefore Their History to Some Degree Reflects the Achievements and Destines of Typical Chinese Merchants at the Time

Powerful informal institutional arrangements in a weak legal environment: A study of the governance structure in the Chinese Shanxi piaohao Abstract1 Shanxi piaohao, arguably are the most important Chinese indigenous financial institutions in Chinese economic history, emerged in one particular province. In a weak legal environment to protect shareholders’ capital, these Shanxi piaohao developed a unique governance structure to discipline and incentivise far flung employees. During their existence, the piaohao dominated the Chinese domestic remittance market for decades and made a great contribution to the economy. However, as with their expansion and together with the external business environment became more unpredictable, the piaohao’s governance structure began malfunctioning. Concentrating on their management and incentive mechanism, this paper explores how the piaohao successfully governed their distant employees at first but failed to manage their employees and innovate their governance structure as they developed. In 1823, in a small town in Shanxi, there emerged a firm named Rishengchang. For the first time we see a firm naming itself a piaohao [票号], which means a business enterprise [hao 号] that specialises in transmitting drafts [piao 票]. Following this, a group of piaohao sprang up in three towns in the same province, Pingyao, Qixian and Taigu, which quickly opened branches all over China. As China’s first financial intermediaries specialising in remittances, these Shanxi piaohao for decades played an important role in the Chinese financial market. However, almost a hundred years after they set up, their whole system collapsed and the piaohao disappeared from history. During their existence, the Shanxi piaohao made a great contribution to the Chinese economy. -

The Mechanism of Paper Money in Yuan China

The Silver Standard as a Discipline on Money Over-Issuances: The Mechanism of Paper Money in Yuan China Hanhui Guan (School of Economics, Peking University, Beijing, 100871, China; [email protected]) Jie Mao (School of International Trade and Economics, University of International Business and Economics, Beijing, 100029, China; [email protected]) Corresponding with the author: Hanhui Guan. School of Economics, Peking University, No. 5 Yiheyuan Road, Haidian District, Beijing, 100871, P. R. China. Email: [email protected]. Phone (office): +86-10-62753493. The Silver Standard as a Discipline on Money Over-Issuances: The Mechanism of Paper Money in Yuan China Abstract: The Yuan was the first dynasty both in Chinese and world history to use paper money as its sole medium of circulation, and also established the earliest silver standard. This paper explores the impact of paper money in Yuan China. We find that: (1) At the beginning of its regime, due to the strict constraints of the silver standard on money issuances, the value of paper money was stable. (2) Since the middle stage of the dynasty, the central government had to finance fiscal deficits by issuing more paper money, and inflation was thus unavoidable. Our empirical results also demonstrate that fiscal pressure from multiple provincial rebellions was the most important factor driving the government to issue more paper money; however, the emperor’s largesse, which had been viewed as another source of fiscal deficits by most traditional historians, had no significant effect on the over-issuance of paper money. (3) When the monetary standard switched from silver to paper money, the impact of fiscal deficits, which were driving more paper money issuances, became much more severe. -

Capitalizing China

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Capitalizing China Volume Author/Editor: Joseph P. H. Fan and Randall Morck, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-23724-9; 978-0-226-23724-4 (cloth) Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/morc10-1 Conference Date: December 15-16, 2009 Publication Date: November 2012 Chapter Title: Financial Strategies for Nation Building Chapter Author(s): Zhiwu Chen Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c12070 Chapter pages in book: (p. 313- 333) 7 Financial Strategies for Nation Building Zhiwu Chen 7.1 Introduction It is hard for historians to ignore the cyclical nature of Chinese history: every forty to fi fty years there was a peasant revolt, and every two to three hundred years there was a change of dynasty. For two thousand years, this pattern has continued. Those interested in China’s future will naturally ask: Will history repeat itself? What should be done to avoid the cycle? Of course, different people will have different answers. Given the advances in technology, it may seem that guided missiles, airplanes, and night vision would stifl e any peasant revolt today. Centuries ago, before the development of modern warfare technologies, revolting peasants and the government army were evenly matched in terms of weaponry. It was not difficult for revolting peasants to equip themselves with arms similar to their counter- parts in the national army. More charged by their determination and pas- sion to revolt, the peasants were a force that could successfully overthrow a dynasty. -

Arresting Flows, Minting Coins, and Exerting Authority in Early Twentieth-Century Kham

Victorianizing Guangxu: Arresting Flows, Minting Coins, and Exerting Authority in Early Twentieth-Century Kham Scott Relyea, Appalachian State University Abstract In the late Qing and early Republican eras, eastern Tibet (Kham) was a borderland on the cusp of political and economic change. Straddling Sichuan Province and central Tibet, it was coveted by both Chengdu and Lhasa. Informed by an absolutist conception of territorial sovereignty, Sichuan officials sought to exert exclusive authority in Kham by severing its inhabitants from regional and local influence. The resulting efforts to arrest the flow of rupees from British India and the flow of cultural identity entwined with Buddhism from Lhasa were grounded in two misperceptions: that Khampa opposition to Chinese rule was external, fostered solely by local monasteries as conduits of Lhasa’s spiritual authority, and that Sichuan could arrest such influence, the absence of which would legitimize both exclusive authority in Kham and regional assertions of sovereignty. The intersection of these misperceptions with the significance of Buddhism in Khampa identity determined the success of Sichuan’s policies and the focus of this article, the minting and circulation of the first and only Qing coin emblazoned with an image of the emperor. It was a flawed axiom of state and nation builders throughout the world that severing local cultural or spiritual influence was possible—or even necessary—to effect a borderland’s incorporation. Keywords: Sichuan, southwest China, Tibet, currency, Indian rupee, territorial sovereignty, Qing borderlands On December 24, 1904, after an arduous fourteen-week journey along the southern road linking Chengdu with Lhasa, recently appointed assistant amban (Imperial Resident) to Tibet Fengquan reached Batang, a lush green valley at the western edge of Sichuan on the province’s border with central Tibet. -

Research on the Reform of Mushi Tusi and Its Influence

2018 International Conference on Educational Research, Economics, Management and Social Sciences (EREMS 2018) Research on the Reform of MuShi Tusi and Its Influence Shuang Liang Southwest Institute of Nationalities, Southwest Minzu University, Chengdu, 610041, China Keywords: Mushi Tusi; Replacement of Tusi chieftains with government-appointed officials; Policy of Controlling Tibet Abstract: During the 470 years of the existence of Mushi in Northwest Yunnan, it was the epitome of the rise of China's Tusi system from the Yuan Dynasty to the prosperity of the Ming Dynasty and the decline of the Qing Dynasty. The reasons for the reform of Mushi Tusi can also fully reflect that the existence and abolishment of the Tusi system is influenced by the central dynasty's borderland policy. By combing the process and its influence on the reform of Mushi Tusi, this paper makes it clear that the reform of Mushi is related to the adjustment of the Qing government's policy on Tibet and to ensure the smooth route of the Qing army to Tibet. 1. Introduction The Mushi Tusi in northwest Yunnan rose from the Yuan Dynasty, reached its peak after the Ming Dynasty, and finally was diverted in the early Qing Dynasty. During the 470 years of its existence, "When the army came to attack, they bowed down and became king when they retreated, so there was no great war for generations, and there were plenty of minerals, and the leader was richer than any other leader." [1]Mushi Tusi for the Naxi people in the Han, Tibetan and other ethnic struggle in the gap to survive, while the continuous development, but also for other ethnic minorities in Northwest Yunnan to create a relatively stable living environment; As a local leader, he made positive contributions to the construction of the border and the control of Tibet by the central government on the basis of regional stability. -

Admiralty Dock 166 Agricultural Experimentation Site Nongshi

Index Admiralty Dock 166 Bishu shanzhuang 避暑山莊 88 Agricultural Experimentation Site nongshi bochuan剝船 125, 126 shiyan suo 農事實驗所 97 Bodde, Derk 295, 299 All-Hankou Guild Alliance Ge huiguan Bodolec, Caroline 28 各會館公所聯合會 gongsuo lianhe hui 327 bondservants 79, 82, 229, 264 Amelung, Iwo 88, 89 booi 264 American Banknote Company 237, 238 bound labour 60, 349 American Presbyterian Mission Press 253 Boxer Rebellion 143, 315, 356 Amoy. See Xiamen Bradstock, Timothy 327, 330, 331 潮州庵埠廠 Anfu, Chaozhou prefecture 188 brass utensils 95 Anhui 79, 120, 124, 132, 138, 139, 141, 172, 196, Bray, Francesca 25, 28, 317 249, 325, 342 bricklayers zhuanjiang 磚匠 91 安慶 Anqing 138 brickmakers 113 apprentices 99, 101, 102, 329, 333, 336, 337, 346 British Columbia 174 Arsenal 137, 146 brocade weavers 334 Arsenal wages 197, 199 Brokaw, Cynthia 28, 247, 248, 250, 251, 252, 255, artisan households 52 270, 274 artisan registration 94, 95 Brook, Timothy 62 匠体 artisan style jiangti 231 Bureau for Crafts gongyi ju 工藝局 97 Attiret, Denis 254, 269 Bureau for Weights and Measures quanheng Audemard 159, 169 duliang ju 權衡度量局 97 Auditing Office jieshen ku 節慎庫 75 Bureau of Construction yingshan qingli si 營繕 清吏司 74, 77, 106, 111, 335 baitang’a 栢唐阿 263 Bureau of Forestry and Weights yuheng qingli bang 幫 323, 331, 338, 342, 343 si 虞衡清吏司 74, 77 banner 263, 264, 265, 266, 267, 278 Bureau of Irrigation and Transportation dushui baofang 報房 234 qingli si 都水清吏司 75, 77 baogongzhi 包工制 196 Burger, Werner 28, 77 baogong 包工 112 Burgess, John S. 29, 326, 330, 336, 338 Baoquan ju 寳泉局 78, 107 -

Download Here

ISABEL SUN CHAO AND CLAIRE CHAO REMEMBERING SHANGHAI A Memoir of Socialites, Scholars and Scoundrels PRAISE FOR REMEMBERING SHANGHAI “Highly enjoyable . an engaging and entertaining saga.” —Fionnuala McHugh, writer, South China Morning Post “Absolutely gorgeous—so beautifully done.” —Martin Alexander, editor in chief, the Asia Literary Review “Mesmerizing stories . magnificent language.” —Betty Peh-T’i Wei, PhD, author, Old Shanghai “The authors’ writing is masterful.” —Nicholas von Sternberg, cinematographer “Unforgettable . a unique point of view.” —Hugues Martin, writer, shanghailander.net “Absorbing—an amazing family history.” —Nelly Fung, author, Beneath the Banyan Tree “Engaging characters, richly detailed descriptions and exquisite illustrations.” —Debra Lee Baldwin, photojournalist and author “The facts are so dramatic they read like fiction.” —Heather Diamond, author, American Aloha 1968 2016 Isabel Sun Chao and Claire Chao, Hong Kong To those who preceded us . and those who will follow — Claire Chao (daughter) — Isabel Sun Chao (mother) ISABEL SUN CHAO AND CLAIRE CHAO REMEMBERING SHANGHAI A Memoir of Socialites, Scholars and Scoundrels A magnificent illustration of Nanjing Road in the 1930s, with Wing On and Sincere department stores at the left and the right of the street. Road Road ld ld SU SU d fie fie d ZH ZH a a O O ss ss U U o 1 Je Je o C C R 2 R R R r Je Je r E E u s s u E E o s s ISABEL’SISABEL’S o fie fie K K d d d d m JESSFIELD JESSFIELDPARK PARK m a a l l a a y d d y o o o o d d e R R e R R R R a a S S d d SHANGHAISHANGHAI -

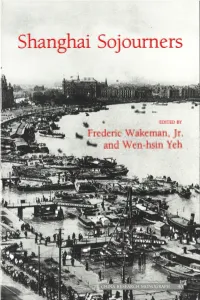

Shanghai Sojourners

CHINA RESEARCH MONOGRAPH 40 FM, INSTITUTE OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES ~~ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA • BERKELEY C(S CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES Shanghai Sojourners EDITED BY Frederic Wakeman, Jr., and Wen-hsin Yeh A publication of the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California at Berkeley. Although the Institute of East Asian Studies is responsible for the selec tion and acceptance of manuscripts in this series, responsibility for the opinions expressed and for the accuracy of statements rests with their authors. Correspondence may be sent to: Ms. Joanne Sandstrom, Managing Editor Institute of East Asian Studies University of California Berkeley, California 94 720 The China Research Monograph series, whose first title appeared in 1967, is one of several publications series sponsored by the Institute of East Asian Studies in conjunction with its constituent units. The others include the Japan Research Monograph series, the Korea Research Monograph series, the Indochina Research Monograph series, and the Research Papers and Policy Studies series. A list of recent publications appears at the back of the book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shanghai sojourners I Frederic E. Wakeman, Jr. , Wen-hsin Yeh, editors. p. em. - (China research monograph ; no. 40) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55729-035-0 (paper) : $20.00 l. Shanghai (China)-History. I. Wakeman, Frederic E. II . Yeh, Wen Hsin. III. Series. DS796.5257S57 1992 95l.l'32-dc20 92-70468 CIP Copyright © 1992 by The Regents of the University of California ISBN 1-55729-035-0 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 92-70468 Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. -

The Designed Thinking of the China Numismatic Museum

Yao Shuomin THE DESIGNED THINKING OF THE CHINA NUMISMATIC MUSEUM Proceedings of the ICOMON meetings held in: Stavanger, Norway, 1995, Vienna, Austria, 1996 / Memoria de las reuniones de ICOMON celebradas en: Stavanger, Noruega, 1995, Viena, Austria, 1996 [Madrid] : Museo Casa de la Moneda, [1997] 269 p. – ISBN 84-88298-03-X., pp. 66-68 Downloaded from: www.icomon.org THE DESIGNED THINKING OF THE CHINA NUMISMATIC MUSEUM Yao Shuomin China Numismatic Museum Beijing, China The China Numismatic Museum was established in 1992. It covers about one thousand five hundred square meters, and is part of the People's Bank of China. The main exhibition of the Museum is called "Chinese Currency", which means the main content of the exhibition is the history of Chinese Currency. In China, exhibitions about the history of currency were often organized in various places. They all give a survey about the Chinese currency in a chronological way. This method enables the public to discover the historical lineage. However, most coins of various Chinese dynasties were round with a square hole. The only difference is the Chinese characters. Although most of the specialists would like such an exhibition in order to admire some rare coins, we think this option is less appropriate for the average visitor. So, we planned a new design for our museum. The principle we had in mind was that both academic specialists and the public should enjoy the museum. There is a Chinese saying for this: "Enjoy both refiner and vulgar". This thinking was embodied in two aspects: substance and form. The first is substance. -

Tibet Was Never Part of China Before 1950: Examples of Authoritative Pre-1949 Chinese Documents That Prove It

Article Tibet was Never Part of China Before 1950: Examples of Authoritative pre-1949 Chinese Documents that Prove It Hon-Shiang LAU Abstract The claim ‘Tibet has been part of China since antiquity’ is crucial for the PRC to legitimize her annexation of Tibet in 1950. However, the vast amount of China’s pre-1949 primary-source records consistently indicate that this claim is false. This paper presents a very small sample of these records from the Ming and the Qing dynasties to illustrate how they unequivocally contradict PRC’s claim. he People’s Republic of China (PRC) claims that ‘Tibet has been part of China T since antiquity西藏自古以来就是中国的一部分.’ The Central Tibet Administration (CTA), based in Dharamshala in India, refuses to accede to this claim, and this refusal by the CTA is used by the PRC as: 1. A prima facie proof of CTA’s betrayal to her motherland (i.e., China), and 2. Justification for not negotiating with the CTA or the Dalai Lama. Why must the PRC’s insist that ‘Tibet has been part of China since antiquity’? China is a signatory to the 1918 League-of-Nations Covenants and the 1945 United- Nations Charter; both documents prohibit future (i.e., post-1918) territorial acquisitions via conquest. Moreover, the PRC incessantly paints a sorry picture of Prof. Hon-Shiang LAU is an eminent Chinese scholar and was Chair Professor at the City University of Hong Kong. He retired in 2011 and has since then pursued research on Chinese government records and practices. His study of Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming, and Manchu period official records show that Tibet was never treated as part of China.