EXECUTIVE SUMMARY to MALTA PROPERTY REPORT. Appendix I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rise and Fall of the Malta Railway After

40 I FEBRUARY 28, 2021 THE SUNDAY TIMES OF MALTA THE SUNDAY TIMES OF MALTA FEBRUARY 28, 2021 I 41 LIFEANDWELLBEING HISTORY Map of the route of It hap~ened in February the Malta Railway /Via/ta Rise and fall Of the VALLETTA Malta Railway after • • • Employees of the Malta Railway pose for a group photograph at its ~naugurat1ons f'famrun Station in 1924. Bombes) on to Hamrun Sta the Attard-Mdina road through Because of debts, calculated to have been in the region of THE MALTA RAILWAY CO. LTD. .in 1883' and 1892 tion. At Hamrun, there was a a 25-yard-long tunnel and then double track w.ith two plat up the final steep climb to £80,000, the line closed down LOCOMOTIVES - SOME TECHNICAL DATA servic.e in Valletta. Plans were The Malta Railways Co. Ltd in forms and side lines leading to Rabat which was the last termi on Tuesday, April 1, 1890, but JOSEPH F. submitted by J. Scott Tucker in augurated its service at 3pm on the workshops which, by 1900, nus till 1900. In that year, the government reopened it on GRIMA 1870, Major Hutchinson in Wednesday, February 28, 1883, were capable of major mainte line was extended via a half Thursday, February 25, 1892. No. Type CyUnders Onches) Builder Worlm No. Data 1873, Architect Edward Rosen amid great enthusiasm. That af nance and engineering work. mile tunnel beneath Mdina to During the closure period, 1. 0-6-0T, 10Yz x 18, Manning Wardle 842, 1882 Retired casual bush in 1873 and George Fer ternoon, the guests were taken Formerly, repairs and renova the Museum Station just below works on buildings were car 2. -

Gazzetta Tal-Gvern Ta' Malta

Nru./No. 20,582 Prezz/Price €2.70 Gazzetta tal-Gvern ta’ Malta The Malta Government Gazette L-Erbgħa, 3 ta’ Marzu, 2021 Pubblikata b’Awtorità Wednesday, 3rd March, 2021 Published by Authority SOMMARJU — SUMMARY Avviżi tal-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar ....................................................................................... 1869 - 1924 Planning Authority Notices .............................................................................................. 1869 - 1924 It-3 ta’ Marzu, 2021 1869 PROĊESS SĦIĦ FULL PROCESS Applikazzjonijiet għal Żvilupp Sħiħ Full Development Applications Din hija lista sħiħa ta’ applikazzjonijiet li waslu għand This is a list of complete applications received by the l-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar. L-applikazzjonijiet huma mqassmin Planning Authority. The applications are set out by locality. bil-lokalità. Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq dawn l-applikazzjonijiet Any representations on these applications should be sent in għandhom isiru bil-miktub u jintbagħtu fl-uffiċini tal-Awtorità writing and received at the Planning Authority offices or tal-Ippjanar jew fl-indirizz elettroniku ([email protected]. through e-mail address ([email protected]) within mt) fil-perjodu ta’ żmien speċifikat hawn taħt, u għandu the period specified below, quoting the reference number. jiġi kkwotat in-numru ta’ referenza. Rappreżentazzjonijiet Representations may also be submitted anonymously. jistgħu jkunu sottomessi anonimament. Is-sottomissjonijiet kollha lill-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar, All submissions to the Planning Authority, -

Malta & Gozo Directions

DIRECTIONS Malta & Gozo Up-to-date DIRECTIONS Inspired IDEAS User-friendly MAPS A ROUGH GUIDES SERIES Malta & Gozo DIRECTIONS WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Victor Paul Borg NEW YORK • LONDON • DELHI www.roughguides.com 2 Tips for reading this e-book Your e-book Reader has many options for viewing and navigating through an e-book. Explore the dropdown menus and toolbar at the top and the status bar at the bottom of the display window to familiarize yourself with these. The following guidelines are provided to assist users who are not familiar with PDF files. For a complete user guide, see the Help menu of your Reader. • You can read the pages in this e-book one at a time, or as two pages facing each other, as in a regular book. To select how you’d like to view the pages, click on the View menu on the top panel and choose the Single Page, Continuous, Facing or Continuous – Facing option. • You can scroll through the pages or use the arrows at the top or bottom of the display window to turn pages. You can also type a page number into the status bar at the bottom and be taken directly there. Or else use the arrows or the PageUp and PageDown keys on your keyboard. • You can view thumbnail images of all the pages by clicking on the Thumbnail tab on the left. Clicking on the thumbnail of a particular page will take you there. • You can use the Zoom In and Zoom Out tools (magnifying glass) to magnify or reduce the print size: click on the tool, then enclose what you want to magnify or reduce in a rectangle. -

46601932.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OAR@UM BULLETIN OF THE ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF MALTA (2012) Vol. 5 : 57-72 A preliminary account of the Auchenorrhyncha of the Maltese Islands (Hemiptera) Vera D’URSO1 & David MIFSUD2 ABSTRACT. A total of 46 species of Auchenorrhyncha are reported from the Maltese Islands. They belong to the following families: Cixiidae (3 species), Delphacidae (7 species), Meenoplidae (1 species), Dictyopharidae (1 species), Tettigometridae (2 species), Issidae (2 species), Cicadidae (1 species), Aphrophoridae (2 species) and Cicadellidae (27 species). Since the Auchenorrhyncha fauna of Malta was never studied as such, 40 species reported in this work represent new records for this country and of these, Tamaricella complicata, an eastern Mediterranean species, is confirmed for the European territory. One species, Balclutha brevis is an established alien associated with the invasive Fontain Grass, Pennisetum setaceum. From a biogeographical perspective, the most interesting species are represented by Falcidius ebejeri which is endemic to Malta and Tachycixius remanei, a sub-endemic species so far known only from Italy and Malta. Three species recorded from Malta in the Fauna Europaea database were not found during the present study. KEY WORDS. Malta, Mediterranean, Planthoppers, Leafhoppers, new records. INTRODUCTION The Auchenorrhyncha is represented by a large group of plant sap feeding insects commonly referred to as leafhoppers, planthoppers, cicadas, etc. They occur in all terrestrial ecosystems where plants are present. Some species can transmit plant pathogens (viruses, bacteria and phytoplasmas) and this is often a problem if the host-plant happens to be a cultivated plant. -

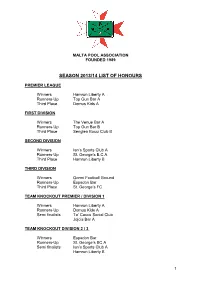

2013/14 List of Honours

MALTA POOL ASSOCIATION FOUNDED 1989 SEASON 2013/14 LIST OF HONOURS PREMIER LEAGUE Winners Hamrun Liberty A Runners-Up Top Gun Bar A Third Place Domus Kids A FIRST DIVISION Winners The Venue Bar A Runners-Up Top Gun Bar B Third Place Senglea Bocci Club B SECOND DIVISION Winners Ian’s Sports Club A Runners-Up St. George’s B.C A Third Place Hamrun Liberty B THIRD DIVISION Winners Qormi Football Ground Runners-Up Espadon Bar Third Place St. George’s FC TEAM KNOCKOUT PREMIER / DIVISION 1 Winners Hamrun Liberty A Runners-Up Domus Kids A Semi finalists Ta’ Caccu Social Club Jojo’s Bar A TEAM KNOCKOUT DIVISION 2 / 3 Winners Espadon Bar Runners-Up St. George’s BC A Semi finalists Ian’s Sports Club A Hamrun Liberty B 1 CHRISTMAS CUP 2013 Winners Hamrun Liberty A Runners-Up Domus Kids A Semi-finalists The Venue Bar A Top Gun Bar B SUPER CUP Winners Hamrun Liberty A MENS RANKING TOURNAMENT NO. 1 Winners Clayton Attard (Top Gun Bar) Runner-Up Anton Cuschieri (Hamrun Liberty) Semi-finalists Johan Attard (Cospicua Rangers) Miguel Falzon (Top Gun Bar) MENS RANKING TOURNAMENT NO. 2 Winner Kevin Mercieca (Hamrun Liberty) Runner-Up Mario Cutajar (Domus Kids) Semi- finalists Malcolm Azzopardi (Top Gun Bar) Antione Aquilina (Domus Kids) MENS RANKING TOURNAMENT NO. 3 Winner Mario Vassallo (Domus Kids) Runner-Up Christ Tabone (Jojo’s Bar) Semi – finalists Anton Cuschieri (Hamrun Liberty) Ray Caruana (Hamrun Liberty) MENS RANKING TOURNAMENT NO. 4 Winner Johan Attard (Cospicua Rangers) Runner-Up Miguel Falzon (Top Gun Bar) Semi – finalists Christ Tabone (Jojo’s -

Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome MALTA • SICILY • ITALY Led by Dr

Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome MALTA • SICILY • ITALY Led by Dr. Carl Rasmussen MAY 11-22, 2021 organized by Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome / May 11-22, 2021 Malta Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome MAY 11-22, 2021 Fri 14 May Ferry to POZZALLO (SICILY) - SYRACUSE – Ferry to REGGIO CALABRIA Early check out, pick up our box breakfasts, meet the English-speaking assistant at our hotel and transfer to the port of Malta. 06:30am Take a ferry VR-100 from Malta to Pozzallo (Sicily) 08:15am Drive to Syracuse (where Paul stayed for three days, Acts 28.12). Meet our guide and visit the archeological park of Syracuse. Drive to Messina (approx. 165km) and take the ferry to Reggio Calabria on the Italian mainland (= Rhegium; Acts 28:13, where Paul stopped). Meet our guide and visit the Museum of Magna Grecia. Check-in to our hotel in Reggio Calabria. Dr. Carl and Mary Rasmussen Dinner at our hotel and overnight. Greetings! Mary and I are excited to invite you to join our handcrafted adult “study” trip entitled Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Sat 15 May PAESTUM - to POMPEII Martyrdom in Rome. We begin our tour on Malta where we will explore the Breakfast and checkout. Drive to Paestum (435km). Visit the archeological bays where the shipwreck of Paul may have occurred as well as the Island of area and the museum of Paestum. Paestum was a major ancient Greek city Malta. Mark Gatt, who discovered an anchor that may have been jettisoned on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea in Magna Graecia (southern Italy). -

L-4 Ta' Diċembru, 2019

L-4 ta’ Diċembru, 2019 25,349 PROĊESS SĦIĦ FULL PROCESS Applikazzjonijiet għal Żvilupp Sħiħ Full Development Applications Din hija lista sħiħa ta’ applikazzjonijiet li waslu għand This is a list of complete applications received by the l-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar. L-applikazzjonijiet huma mqassmin Planning Authority. The applications are set out by locality. bil-lokalità. Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq dawn l-applikazzjonijiet Any representations on these applications should be sent in għandhom isiru bil-miktub u jintbagħtu fl-uffiċini tal-Awtorità writing and received at the Planning Authority offices or tal-Ippjanar jew fl-indirizz elettroniku ([email protected]. through e-mail address ([email protected]) within mt) fil-perjodu ta’ żmien speċifikat hawn taħt, u għandu the period specified below, quoting the reference number. jiġi kkwotat in-numru ta’ referenza. Rappreżentazzjonijiet Representations may also be submitted anonymously. jistgħu jkunu sottomessi anonimament. Is-sottomissjonijiet kollha lill-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar, All submissions to the Planning Authority, submitted sottomessi fiż-żmien speċifikat, jiġu kkunsidrati u magħmula within the specified period, will be taken into consideration pubbliċi. and will be made public. L-avviżi li ġejjin qed jiġu ppubblikati skont Regolamenti The following notices are being published in accordance 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a) u 11(3) tar-Regolamenti dwar l-Ippjanar with Regulations 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a), and 11(3) of the tal-Iżvilupp, 2016 (Proċedura ta’ Applikazzjonijiet u Development Planning (Procedure for Applications and d-Deċiżjoni Relattiva) (A.L.162 tal-2016). their Determination) Regulations, 2016 (L.N.162 of 2016). Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq l-applikazzjonijiet li ġejjin Any representations on the following applications should għandhom isiru sat-13 ta’ Jannar, 2020. -

The Company Publishes the Financial Analysis Summary

Hal Mann Vella Group plc The Factory Mosta Road Lija LJA 9016 Tel: 21433636 Fax: 21412499 COMPANY ANNOUNCEMENT Hal Mann Vella Group plc (the “Company”) The Company publishes the Financial Analysis Summary Date: 28 July 2015 Reference: 03/2015 In Terms of Chapter 5 of the Listing Rules The company announces publication of the Financial Analysis Summary as per attached document. Louis de Gabriele Company Secretary VAT No: MT 1490 0220 – Co. Reg: C5067 Hal Mann Vella Group p.l.c. Financial Analysis Summary 27 July 2015 The Directors Hal Mann Vella Group p.l.c. The Factory Mosta Road Lija LJA 9016 27 July 2015 Dear Sirs Hal Mann Vella Group p.l.c. Financial Analysis Summary In accordance with your instructions, and in line with the requirements of the Listing Authority Policies, we have compiled the Financial Analysis Summary set out on the following pages and which is being forwarded to you together with this letter. The purpose of the financial analysis is that of summarising key financial data appertaining to Hal Mann Vella Group p.l.c. (the “Group ” or the “Company ”). The data is derived from various sources or is based on our own computations as follows: (a) Historical financial data for the four years ended 31 December 2011 to 31 December 2014 has been extracted from the audited consolidated financial statements of the Company. (b) The forecast data of the Group for the years ending 31 December 2015 and 31 December 2016 has been provided by management of the Company. (c) Our commentary on the results of the Group and on its financial position is based on the explanations provided by the Company. -

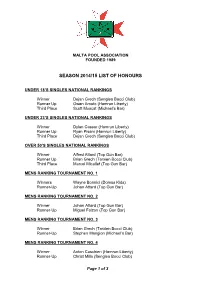

2014/15 List of Honours

MALTA POOL ASSOCIATION FOUNDED 1989 SEASON 2014/15 LIST OF HONOURS UNDER 18’S SINGLES NATIONAL RANKINGS Winner Dejan Grech (Senglea Bocci Club) Runner Up Owen Amato (Hamrun Liberty) Third Place Scott Muscat (Michael’s Bar) UNDER 23’S SINGLES NATIONAL RANKINGS Winner Dylan Cassar (Hamrun Liberty) Runner Up Ryan Pisani (Hamrun Liberty) Third Place Dejan Grech (Senglea Bocci Club) OVER 50’S SINGLES NATIONAL RANKINGS Winner Alfred Attard (Top Gun Bar) Runner Up Brian Grech (Tarxien Bocci Club) Third Place Marcel Micallef (Top Gun Bar) MENS RANKING TOURNAMENT NO. 1 Winners Wayne Bonnici (Domus Kids) Runner-Up Johan Attard (Top Gun Bar) MENS RANKING TOURNAMENT NO. 2 Winner Johan Attard (Top Gun Bar) Runner-Up Miguel Falzon (Top Gun Bar) MENS RANKING TOURNAMENT NO. 3 Winner Brian Grech (Tarxien Bocci Club) Runner-Up Stephen Mangion (Michael’s Bar) MENS RANKING TOURNAMENT NO. 4 Winner Anton Cuschieri (Hamrun Liberty) Runner-Up Christ Mills (Senglea Bocci Club) Page 1 of 3 MENS RANKING TOURNAMENT NO. 5 Winner Christ Tabone (Jojo’s Bar) Runner-Up Clayton Attard (Hamrun Liberty) MENS WORLD QUALIFIER TOURNAMENT 1 Winner Johan Attard (Top Gun Bar) Runner-Up Ray Caruana (Hamrun Liberty) MENS WORLD QUALIFIER TOURNAMENT 2 Winner Clayton Attard (Hamrun Liberty) Runner-Up Christ Mills (Senglea Bocci Club) MENS SINGLES CHAMPIONSHIPS Winner Ryan Pisani (Hamrun Liberty) Runner-Up Antione Aquilina (Domus Kids) CHRISTMAS CUP TOURNAMENT Winners Hamrun Liberty A Runners-Up Domus Kids A EASTER CUP TOURNAMENT Winners Hamrun Liberty A Runners-Up Top Gun Bar A TEAM KNOCKOUT DIVISION 2 / 3 Winners Michael’s Bar Runners-Up Qormi Football Ground A TEAM KNOCKOUT PREMIER / DIVISION 1 Winners Hamrun Liberty A Runners-Up Top Gun Bar A THIRD DIVISION Winners Michael’s Bar Runners-Up St. -

Searching for Maltese Forebearers

Journal of Maltese History, volume 3, number 2, 2013 Guide to searching Maltese Ancestors H.V. Wyatt* For much social, historical and medical research, a basic tool is the availability of data about the people. Malta is fortunate in the time-span and details of its records. Church records in Malta began in the sixteenth century and the government Public Registry [PR] started in 1863 so that searching for ancestors is possible. The records are complementary, but are also incomplete and frustrating. While in the past much historical research has looked at earlier times, I have assumed that the most useful period is from 1863 when the PR records give the occupation of the parties. The church records give details of consanguinity. Some Background The records are very dependent on the handwriting of the priest who wrote the certificates for the PR as well as the parish registry. One priest at Qormi had very bad handwriting and many of the names in the parish records and the certificates in the PR cannot be deciphered eg. Zammit or Sammut. He lived for a long time and may well have celebrated some marriages too well, as on several occasions he reversed the parental names of the married couple. Several surnames imply the bearers came from a particular place (eg. Attard, Catania from Sicily and Genovese from Genoa). There is no telling whether people with a particular surname are related – it is likely that unrelated people came at different times to different places, but received the same names. Over the years some surnames have changed eg: Armenio to Armeni about 1869, Cipirott to Chipiotte (Sliema), Degabriele to Gabriele (Vittoriosa), Destefano to Distefano (Sliema), Genius became Genovese (Florianna, Cospicua and Hamrun) with other versions – Genovise, Genuis, Genarus in Valletta, Sliema, Senglea, etc., Mummery to Memory (Senglea), Mackay to Mackey in Valletta and vice versa there and in Hamrun Monsigner and Monsigneur in Valletta, Monsinieur and Musunier (Valletta) Pizzuto to Pezzuto (Cospicua) , Sanchez and Sanges (Valletta), Steer to Stur (Valletta). -

Annual Report 2017 Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 CONTENTS 3 4 9 CEO Water Water Report Resources Quality 14 20 32 Compliance Network Corporate Infrastructure Services Directorate 38 45 48 Strategic Human Unaudited Information Resources Financial Directorate Statement 2017 ANNUAL REPORT CEO REPORT CEO Report 2017 was a busy year for the Water Services quality across Malta. Secondly, RO plants will be Corporation, during which it worked hard to become upgraded to further improve energy efficiency and more efficient without compromising the high quality production capacity. Furthermore, a new RO plant service we offer our customers. will be commissioned in Gozo. This RO will ensure self-sufficiency in water production for the whole During a year, in which the Corporation celebrated island of Gozo. The potable water supply network to its 25th anniversary, it proudly inaugurated the North remote areas near Siġġiewi, Qrendi and Haż-Żebbuġ Wastewater Treatment Polishing Plant in Mellieħa. will be extended. Moreover, ground water galleries This is allowing farmers in the Northern region to will also be upgraded to prevent saline intrusion. benefit from highly polished water, also known as The project also includes the extension of the sewer ‘New Water’. network to remote areas that are currently not WSC also had the opportunity to establish a number connected to the network. Areas with performance of key performance indicator dashboards, produced issues will also be addressed. inhouse, to ensure guaranteed improvement. These Having only been recently appointed to lead the dashboards allow the Corporation to be more Water Services Corporation, I fully recognize that the efficient, both in terms of performance as well as privileges of running Malta’s water company come customer service. -

Of 4 Funeral of the Former Prime Minister and Leader of the Labo

Funeral of the former Prime Minister and Leader of the Labour Party Mr Dom Mintoff Thursday 23rd August 1515 hrs Hearse to leave Mater Dei Hospital to Xintill Str Tarxien. 1530 hrs The coffin will be placed in family Mintoff’s private residence in Xintill Str Tarxien where the family convenes. 1600 hrs The coffin of the late Mr. Dom Mintoff will be carried from his residence to the hearse. The hearse leaves towards Tarxien Parish Church, where the Mayor Mr. Paul Farrugia, the Local Council members and PL committee will pay tribute. Thereafter, the funeral proceeds to Senglea. 1630 hrs Arrival of the hearse in front of Senglea Parish Church where Mayor of Senglea Mr. Justin Camilleri, the Local Council Members, PL Senglea Committee and Band La Vincitrice will lead the funeral cortege, through Victory street next to Senglea Band Club. 1650 hrs The hearse, leaves through Victory Street to Triq ix-Xatt, towards il-Macina, proceeding to Vittoriosa Xatt ir-Risq. 1705 hrs Arrival of the hearse in front of Freedom Monument Vittoriosa where, Mary Spiteri pays tribute, by singing Tema’ 79. Page 1 of 4 1710 hrs Cortege accompanied by Vittoriosa Mayor Mr. John Boxall and the Local Council members, Vittoriosa PL Committee and St. Lawrence Band, where it proceeds to Victory Square. 1725 hrs Cortege proceeds from Victory Square to Maingate Street, accompanied by the Prince of Wales Own Band. 1740 hrs The hearse leaves from Vittoriosa to Cospicua, accompanied by Kalkara Mayor Mr. Michael Cohen, local council members, Kalkara PL committee and Kalkara band clubs i.e.