On Dennis Oppenheim's Marionette Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARTIST - DENNIS OPPENHEIM Born in Electric City, WA, USA, in 1938 Died in New York, NY, USA, in 2011

ARTIST - DENNIS OPPENHEIM Born in Electric City, WA, USA, in 1938 Died in New York, NY, USA, in 2011 EDUCATION - 1964 : Beaux Arts of California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, CA, USA 1967 : Beaux Arts of Stantford University, Palo Alto, CA, US SOLO SHOWS (SELECTION) - 2020 Dennis Oppenheim, Galerie Mitterrand, Paris, France 2019 Dennis Oppenheim, Le dessin hors papier, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Caen, FR 2018 Broken Record Blues, Peder Lund, Oslo NO Violations, Marlborough Contemporary, New York US Straight Red Trees. Alternative Landscape Components, Guild Hall, East Hampton, NY, US 2016 Terrestrial Studio, Storm King Art Center, New Windsor US Three Projections, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, US 2015 Collection, MAMCO, Geneva, CH Launching Structure #3. An Armature for Projections, Halle-Nord, Geneva CH Dennis Oppenheim, Wooson Gallery, Daegu, KR 2014 Dennis Oppenheim, MOT International, London, UK 2013 Thought Collision Factories, Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, UK Sculpture 1979/2006, Galleria Fumagalli & Spazio Borgogno, Milano, IT Alternative Landscape Components, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Bretton, UK 2012 Electric City, Kunst Merano Arte, Merano, IT 1968: Earthworks and Ground Systems, Haines Gallery, San Francisco US HaBeer, Beersheba, ISR Selected Works, Palacio Almudi, Murcia, ES 2011 Dennis Oppenheim, Musee d'Art Moderne et Contemporain, Saint-Etienne, FR Eaton Fine Arts, West Palm Beach, Florida, US Galerie Samuel Lallouz, Montreal, CA Salutations to the Sky, Museo Fundacion Gabarron, New York, US 79 RUE DU TEMPLE -

Zhiyuan Yang Dennis Oppenheim

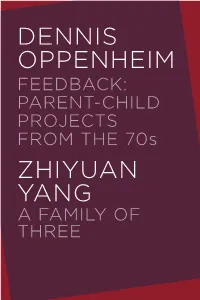

DENNIS OPPENHEIM FEEDBACK: PARENT-CHILD PROJECTS FROM THE 70s ZHIYUAN YANG A FAMILY OF THREE DENNIS OPPENHEIM FEEDBACK: PARENT-CHILD PROJECTS FROM THE 70s ZHIYUAN YANG A FAMILY OF THREE SHIRLEY FITERMAN ART CENTER BOROUGH OF MANHATTAN COMMUNITY COLLEGE, CUNY IN HIS PIONEERING WORK OF THE LATE 1960s AND EARLY 70s , Dennis Oppenheim (1938-2011) went beyond the strictures of Minimalism to investigate and act in the actual world through explorations that engage both the landscape and the body. Perhaps best known for his Land Art works that transcended the confines of traditional sculpture, as well as the limits of the gallery context, Oppenheim’s performance works also pushed multiple boundaries.1 His artistic experimentation unfolded against a tumultuous historical backdrop that was branded by social and political unrest. The United States was enmeshed in a deeply unpopular war in Vietnam, one that provoked massive anti-war demonstrations through the early 70s. Concurrently, a widespread counterculture movement, led by the country’s youth, swept the nation. The turmoil continued with the Watergate scandal, which resulted in a vote by the House of Representatives to impeach then-President Richard Nixon, who resigned in summer 1974. The period was also defined by high unemployment, gas shortages, and rampant inflation. This same moment is marked artistically by a shift away from the strict tenets of Minimalism toward Post-Minimalism, which encompassed a more expansive approach to artmaking and a broad range of visual experimentation, including Process, Conceptual, and Performance Art. Leaving behind the specificity of the object, these practices presented art as encounters subject to physical and temporal conditions. -

Size, Scale and the Imaginary in the Work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim

Larger than life: size, scale and the imaginary in the work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim © Michael Albert Hedger A thesis in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Art History and Art Education UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES | Art & Design August 2014 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Hedger First name: Michael Other name/s: Albert Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: Ph.D. School: Art History and Education Faculty: Art & Design Title: Larger than life: size, scale and the imaginary in the work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Conventionally understood to be gigantic interventions in remote sites such as the deserts of Utah and Nevada, and packed with characteristics of "romance", "adventure" and "masculinity", Land Art (as this thesis shows) is a far more nuanced phenomenon. Through an examination of the work of three seminal artists: Michael Heizer (b. 1944), Dennis Oppenheim (1938-2011) and Walter De Maria (1935-2013), the thesis argues for an expanded reading of Land Art; one that recognizes the significance of size and scale but which takes a new view of these essential elements. This is achieved first by the introduction of the "imaginary" into the discourse on Land Art through two major literary texts, Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726) and Shelley's sonnet Ozymandias (1818)- works that, in addition to size and scale, negotiate presence and absence, the whimsical and fantastic, longevity and death, in ways that strongly resonate with Heizer, De Maria and especially Oppenheim. -

Marlborough Gallery

Marlborough DENNIS OPPENHEIM 1938 — Born in Electric City, Washington 2011 — Died in New York, New York The artist lived and worked in New York, New York. Education 1965 — B.F.A., the School of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, California 1966 — M.F.A., Stanford University, Palo Alto, California Solo Exhibitions 2020 — Dennis Oppenheim, Galerie Mitterand, Paris, France 2019 — Feedback: Parent Child Projects from the 70s, Shirley Fiterman Art Center, The City University of New York, BMCC, New York, New York 2018 — Violations, 1971 — 1972, Marlborough Contemporary, New York, New York Broken Record Blues, Peder Lund, Oslo, Sweden 2016 — Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois Storm King Art Center, New Windsor, New York 2015 — Wooson Gallery, Daegu, Korea MAMCO, Geneva, Switzerland Halle Nord, Geneva, Switzerland 2014 — MOT International, London, United Kingdom Museo Magi'900, Pieve di Cento, Italy 2013 — Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, United Kingdom Museo Pecci Milano, Milan, Italy Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Yorkshire, United Kingdom Marlborough 2012 — Centro de Arte Palacio, Selected Works, Murcia, Spain Kunst Merano Arte, Merano, Italy Haines Gallery, San Francisco, California HaBeer, Beersheba, Israel 2011 — Musée d'Art moderne Saint-Etienne Metropole, Saint-Priest-en-Jarez, France Eaton Fine Arts, West Palm Beach, Florida Galerie Samuel Lallouz, Quebec, Canada The Carriage House, Gabarron Foundation, New York, New York 2010 — Thomas Solomon Gallery, Los Angeles, California Royale Projects, Indian Wells, California Buschlen Mowatt Galleries, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Galleria Fumagalli, Bergamo, Italy Gallerie d'arts Orler, Venice, Italy 2009 — Marta Museum, Herford, Germany Scolacium Park, Catanzaro, Italy Museo Marca, Catanzarto, Italy Eaton Fine Art, West Palm Beach, Florida Janos Gat Gallery, New York, New York 2008 — Ace Gallery, Beverly Hills, California 4 Culture Gallery, Seattle, Washington Edelman Arts, New York, New York D.O. -

Bibliography (Pdf/63Kb)

2006 • Connecting Worlds, Shikata Yukiko, NTT InterCommunication Center, Tokyo, Japan • Escritos de Artistas, Jorge Zahar, Jorge Zahar Editor Ltda., Rio de Janerio, Brazil • Ethics and the Visual Arts, E.A. King and G. Levin, Eds, Allworth Press, New York • Art Metropole: the Top 100, K. Scott and J. Shaughnesy, National Gallery of Art, Ottawa, Canada • Art and Video in the 70s, Silvana Editoriale Spa, Milan, Italy • Collection of the Fondation Cartier at MOT, Foil Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan 2005 • Slideshow: Projected images in Contemporary Art, Darcie Alexander, Baltimore Museum of Art, American University Presses, Pennsylvania • Odd Lots: Revisiting Gordon Matta-Clark‘s Fake Estates, Jeffrey Kastner, Sina Najafi and Frances Richard, Eds. Cabinet Books, New York • 40 years at the ICA, Johanna Plummer, Ed. Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, PA • Superstars: Warhol to Madonna, Sigrid Mittersteiner, Ed., Hatje Cantz Verlag, Germany • Comme le reve, le dessin, Centre Pompidou , Paris, France • Dennis Oppenheim: Project Drawings, Demetrio Paparoni, In Arco Books, Torino, Italy • La Poetica de lo Neutro, Victoria Combalia, Debolsillo, Barcelona, Spain • Domicile: prive/public, Lorand Hegyi, Somogy Editions d‘Art, Paris 2004 • The Context of Art/ The Art of Context, Seth Siegelaub, Marion Fricke and Roswitha Fricke, Navado Press, Trieste, Italy • Ana Mendieta Earth Body, Olga M. Vison, Hirshhorn Museum and Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany • Ready to Shoot Fernsehgalerie Gerry Schum, Ulrike Groos, Snoek Verlagsgesellschaft, Cologne, Germany • Art in Transit, Pallas Lombardi, Charlotte Area Transit System, Charlotte, North Carolina, U.S.A. • The Museum: Conditions and Spaces, Andrea Douglas, University of Virginia Art Museum, Charlottesville, Virginia, U.S.A. -

Minimal Art and Body Politics in New York City, 1961-1975 By

Minimal Art and Body Politics in New York City, 1961-1975 by Christopher M. Ketcham M.A. Art History, Tufts University, 2009 B.A. Art History, The George Washington University, 1998 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ARCHITECTURE: HISTORY AND THEORY OF ART AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER 2018 © 2018 Christopher M. Ketcham. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author:__________________________________________________ Department of Architecture August 10, 2018 Certified by:________________________________________________________ Caroline A. Jones Professor of the History of Art Thesis Supervisor Accepted by:_______________________________________________________ Professor Sheila Kennedy Chair of the Committee on Graduate Students Department of Architecture 2 Dissertation Committee: Caroline A. Jones, PhD Professor of the History of Art Massachusetts Institute of Technology Chair Mark Jarzombek, PhD Professor of the History and Theory of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Tom McDonough, PhD Associate Professor of Art History Binghamton University 3 4 Minimal Art and Body Politics in New York City, 1961-1975 by Christopher M. Ketcham Submitted to the Department of Architecture on August 10, 2018 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture: History and Theory of Art ABSTRACT In the mid-1960s, the artists who would come to occupy the center of minimal art’s canon were engaged with the city as a site and source of work. -

Dennis Oppenheim

! DENNIS OPPENHEIM BIOGRAFIA Nato nel 1938 a Electric City, Washington US Morto nel 2011 a New York US FORMAZIONE 1964 Laurea in Belle Arti presso California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland US 1967 laurea magistrale in Belle Arti presso Stanford University, Palo Alto US MOSTRE PERSONALI 2019 Dennis Oppenheim, Le dessin hors papier, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Caen FR 2018 Broken Record Blues, Peder Lund, Oslo NO Violations, Marlborough Contemporary, New York US Straight Red Trees. Alternative Landscape Components, Guild Hall, East Hampton, New York US 2016 Terrestrial Studio, Storm King Art Center, New Windsor US Three Projections, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago US 2015 Collection, MAMCO, Geneva CH Launching Structure #3. An Armature for Projections, Halle-Nord, Geneva CH Dennis Oppenheim, Wooson Gallery, Daegu KR 2014 Dennis Oppenheim, MOT International, London UK 2013 Thought Collision Factories, Henry Moore Institute, Leeds UK Sculpture 1979/2006, Galleria Fumagalli & Spazio Borgogno, Milano IT Alternative Landscape Components, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Breton UK 2012 Electric City, Kunst Merano Arte, Merano IT 1968: Earthworks and Ground Systems, Haines Gallery, San Francisco US HaBeer, Beersheba ISR Selected Works, Palacio Almudi, Murcia ES ! ! ! 2011 Dennis Oppenheim, Musee d'Art Moderne et Contemporain, Saint-Etienne FR Eaton Fine Arts, West Palm Beach, Florida US Galerie Samuel Lallouz, Montreal CA Salutations to the Sky, Museo Fundacion Gabarron, New York US 2010 Thomas Solomon Gallery, Los Angeles US Royale Projects, Indian -

Press Release

ALICE AYCOCK DENNIS OPPENHEIM PRESS RELEASE on view from 10 December 2020 For press inquiries please contact Appointments encouraged, mask required for entry Lukas Hall at (212) 541-4900 or [email protected] NEW YORK. The Directors of Marlborough Gallery are pleased to present a special exhibition featuring several large- scale works by Alice Aycock alongside an installation by Dennis Oppenheim. The exhibition will be viewable on the ground floor of our newly renovated space located at 545 West 25th Street. This two-person exhibition follows Aycock’s highly successful summer exhibition in Stockholm at the Royal Djurgården hosted by the Princess Estelle Cultural Foundation. With memories of the Mudd Club, the Odeon, Debby Harry and ‘Heart of Glass,’ we take a moment to reunite two kindred spirits in a play of synergistic works that have long and deep histories of particular resonance with the downtown scene in New York. ALICE AYCOCK’s works are intriguing because of their resistance to easy explanations. An early influence was Rem Koolhaas’s Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan. She studied with Robert Morris and the art historian Leo Steinberg at Hunter College where she received her MA. Aycock’s first large-scale architectural work Maze (1972) was created upon finishing her studies at Hunter College in 1971. Her subsequent early show at 112 Greene Street and her association with Gordon Matta-Clark put her solidly in touch with many of the prominent downtown artists of the seventies, such as Mary Miss and Jackie Winsor. Aycock entered into an intense relationship with Dennis Oppenheim and remained lifelong friends, and along with Vito Acconci, were frequently associated by their mutual interests and even greater differences, as shown in the 1979 three-person exhibition at the ICA in Philadelphia entitled ‘Machineworks.’ For a brief time, they even shared a common visual repertoire. -

Dennis Oppenheim: Terrestrial Studio on View at Storm King Through November 13, 2016

DENNIS OPPENHEIM: TERRESTRIAL STUDIO ON VIEW AT STORM KING THROUGH NOVEMBER 13, 2016 Exhibition Traces the Artist’s Lifelong Engagement with Outdoor Space Through Such Major Installations as Dead Furrow and Entrance to a Garden Dead Furrow. 1967/2016. Wood surfaced with organic pigment, PVC pipe. Fabricated at Storm King Art Center. 10 x 40 x 35’ (3 x 12.2 x 10.7m). © Dennis Oppenheim. Courtesy Dennis Oppenheim Estate. Photograph by Jerry L. Thompson. Mountainville, NY, September 8, 2016—Dennis Oppenheim: Terrestrial Studio is currently on view at Storm King Art Center through November 13, 2016. The major exhibition features outdoor and indoor sculpture, installation, sound, film, and photography as well as two major earthworks conceived by the artist, but never fully realized in his lifetime. Terrestrial Studio is organized in close collaboration with the Dennis Oppenheim Estate and includes works on loan and in Storm King’s collection. The exhibition is installed in several locations across Storm King’s landscape including the South Fields, Meadows, and Museum Hill, as well as inside the Museum Building. It is organized by Storm King Director and Chief Curator, David R. Collens; Curator Nora Lawrence, and Assistant Curator Theresa Choi. Also on view is the fourth installment of Storm King’s Outlooks series, featuring site-specific outdoor installations by Josephine Halvorson. Dennis Oppenheim: Terrestrial Studio includes work by Dennis Oppenheim (1938-2011) from different points in his diverse and substantial career. First rising to prominence for earthworks in the late 1960s, Oppenheim ventured outdoors not only to transcend the physical confines of the exhibition space, but also to work beyond the limitations of the gallery setting. -

DENNIS OPPENHEIM 29 MAY > 1St AUG 2020 PRESS RELEASE

DENNIS OPPENHEIM 29 MAY > 1st AUG 2020 PRESS RELEASE OPENING 30 MAY The Galerie Mitterrand is pleased to announce the start of its collaboration with the estate of American artist Dennis Oppenheim in France. For the occasion, a first exhibition devoted to the artist will be held at the gallery from 29 May to 1st August 2020 and will feature a selection of works created by the artist between 1973 and 2008. Dennis Oppenheim’s work is characterized by a multitude of approaches ranging from Land Art to Body Art and includes practices like video, sculpture, installation and even photography. A pioneer of Earth art, alongside Robert Smithson, Walter De Maria, Michael Heizer, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Dennis Oppenheim sought to situate his works in a natural environment by integrating the particularities of the landscape. Earth art originated in the United States in the 1960s. Works associated with the movement would later be grouped under the more generic term Land Art. The artists of the Earth art movement voluntarily positioned their works away from institutional venues and channels by favouring the production of in-situ pieces. Dennis Oppenheim stood out for his conceptual approach, integrating an explicitly social and political dimension. From the start of his career, in order to keep a record of his interventions, Dennis Oppenheim used photography and or film, that became works in their own right. This is the case with Whirlpool-Eye of the Storm, a series of seven photographs documenting a project carried out in the summer of 1973 in the El Mirage (Dry) Lake in the Mojave Desert in California, during which an airplane drew a spiral of white smoke in the sky. -

Oral History Interview with Dennis Oppenheim, 2009 June 23-24

Oral history interview with Dennis Oppenheim, 2009 June 23-24 Funding for this interview provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a digitally recorded interview with Dennis Oppenheim on June 23 and 24, 2009. The interview took place at the artist's studio in New York, New York, and was conducted by Judith O. Richards for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Funding for this interview was provided by a grant from the Terra Foundation for American Art. Dennis Oppenheim and Judith O. Richards have reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview JUDITH O. RICHARDS: This is Judith Richards on June 23, 2009, interviewing Dennis Oppenheim, at 54 Franklin Street, New York City. Disc one, session one. Okay, Dennis, I wanted to first note that this interview is going to pick up where, more or less, the last Archives of American Art interview ended, which was in August 1995. DENNIS OPPENHEIM: Mm-hmm. [Affirmative.] MS. RICHARDS: So mainly we'll be covering the time from then to now. MR. OPPENHEIM: Mm-hmm. [Affirmative.] MS. RICHARDS: Which is a good time. -

Jean-Noel Archive.Qxp.Qxp

THE JEAN-NOËL HERLIN ARCHIVE PROJECT Jean-Noël Herlin New York City 2005 Table of Contents Introduction i Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups 1 Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups. Selections A-D 77 Group events and clippings by title 109 Group events without title / Organizations 129 Periodicals 149 Introduction In the context of my activity as an antiquarian bookseller I began in 1973 to acquire exhibition invitations/announcements and poster/mailers on painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance, and video. I was motivated by the quasi-neglect in which these ephemeral primary sources in art history were held by American commercial channels, and the project to create a database towards the bibliographic recording of largely ignored material. Documentary value and thinness were my only criteria of inclusion. Sources of material were random. Material was acquired as funds could be diverted from my bookshop. With the rapid increase in number and diversity of sources, my initial concept evolved from a documentary to a study archive project on international visual and performing arts, reflecting the appearance of new media and art making/producing practices, globalization, the blurring of lines between high and low, and the challenges to originality and quality as authoritative criteria of classification and appreciation. In addition to painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance and video, the Jean-Noël Herlin Archive Project includes material on architecture, design, caricature, comics, animation, mail art, music, dance, theater, photography, film, textiles and the arts of fire. It also contains material on galleries, collectors, museums, foundations, alternative spaces, and clubs.