Oral History Interview with Dennis Oppenheim, 2009 June 23-24

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Dennis Oppenheim's Marionette Theatre

On Dennis Oppenheim’s marionette theatre Robert Slifkin Figure 1 Dennis Oppenheim, Attempt to Raise Hell, 1974. Seated motorized figure in the image of the artist, cloth and felt suit, wood and steel base, spotlight. Timing device triggers cast head in the image of the artist to lunge forward striking the suspended silver plated bell every sixty seconds. 78.4 x 121 x 91.1 cm. Collection Radchovsky House, Dallas. Photo: Ace Contemporary, Los Angeles. Courtesy Dennis Oppenheim Estate. Dennis Oppenheim’s Attempt to Raise Hell (Figure 1), a motorized effigy of the artist set upon a white plinth that violently bangs its aluminium head upon a large brass bell every three minutes, portrays, in a most striking manner, the romantic theme of artistic creation through bodily and mental suffering. The violent clang of metal on metal produced by the piece resonates loudly and long after the jerky mechanical collision, sounding something like an alarm in the gallery in which the work is exhibited. The work’s sonic resonance imparts its ambition to draw attention to itself and to produce effects beyond its material limits, not only in the space but in the minds and bodies of beholders. The masochistic gesture portrayed by the mechanical figure is capable of engendering powerful feelings in its viewers. One might say that Attempt to Raise Hell dramatizes a foundational conceit of expressionism, in which a sensory experience of a work of art’s creator is vividly conveyed to a beholder through affective means. The use of an inanimate and mechanical surrogate ironizes this dynamic, suggesting how the techniques of such experiential transference are typically more technical than natural. -

ARTIST - DENNIS OPPENHEIM Born in Electric City, WA, USA, in 1938 Died in New York, NY, USA, in 2011

ARTIST - DENNIS OPPENHEIM Born in Electric City, WA, USA, in 1938 Died in New York, NY, USA, in 2011 EDUCATION - 1964 : Beaux Arts of California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, CA, USA 1967 : Beaux Arts of Stantford University, Palo Alto, CA, US SOLO SHOWS (SELECTION) - 2020 Dennis Oppenheim, Galerie Mitterrand, Paris, France 2019 Dennis Oppenheim, Le dessin hors papier, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Caen, FR 2018 Broken Record Blues, Peder Lund, Oslo NO Violations, Marlborough Contemporary, New York US Straight Red Trees. Alternative Landscape Components, Guild Hall, East Hampton, NY, US 2016 Terrestrial Studio, Storm King Art Center, New Windsor US Three Projections, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, US 2015 Collection, MAMCO, Geneva, CH Launching Structure #3. An Armature for Projections, Halle-Nord, Geneva CH Dennis Oppenheim, Wooson Gallery, Daegu, KR 2014 Dennis Oppenheim, MOT International, London, UK 2013 Thought Collision Factories, Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, UK Sculpture 1979/2006, Galleria Fumagalli & Spazio Borgogno, Milano, IT Alternative Landscape Components, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Bretton, UK 2012 Electric City, Kunst Merano Arte, Merano, IT 1968: Earthworks and Ground Systems, Haines Gallery, San Francisco US HaBeer, Beersheba, ISR Selected Works, Palacio Almudi, Murcia, ES 2011 Dennis Oppenheim, Musee d'Art Moderne et Contemporain, Saint-Etienne, FR Eaton Fine Arts, West Palm Beach, Florida, US Galerie Samuel Lallouz, Montreal, CA Salutations to the Sky, Museo Fundacion Gabarron, New York, US 79 RUE DU TEMPLE -

Joel Shapiro Press Release FINAL

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DOMINIQUE LÉVY TO PRESENT THE FIRST COMPREHENSIVE SURVEY OF JOEL SHAPIRO’S EARLY WOOD WALL RELIEF SCULPTURES ALONGSIDE A MAJOR NEW INSTALLATION Joel Shapiro October 28, 2016 – January 7, 2017 Dominique Lévy 909 Madison Avenue, New York New York … Dominique Lévy is pleased to present the first survey of early wood reliefs by the American sculptor Joel Shapiro, organized with Olivier Renaud-Clément. These works, created between 1978 and 1980, will be on view alongside a new site-specific installation. The exhibition will foreground work from the late 1970s, demonstrating the trajectory of Shapiro’s career, over the course of which the artist has continually pursued ideas of color and mass, culminating in a recent body of room-size sculptural installations. Dominique Lévy will publish a monograph in conjunction with the exhibition featuring texts by David Raskin and Phyllida Barlow and poems by Peter Cole and Ange Mlinko, as well as full documentation of the wood reliefs. This marks the Untitled, 1978. Wood and paint. 5 1/4 x 5 1/4 x 3 inches (13.3 x 13.3 x 7.6 cm). © 2016 Joel Shapiro first time the series will be comprehensively surveyed. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Shapiro has worked with the idea of form collapsing since 2002; he views his work until this point as building up to this “moment of discovery that I can get the work off the floor and be more playful in the air.”1 He describes these large-scale installations as being “the projection of thought into space without the constraint of architecture.” Shapiro will create a new site-specific installation for the exhibition, which will occupy the second floor of Dominique Lévy Gallery. -

Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 1988 The Politics of Experience: Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960s Maurice Berger Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1646 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Dick Polich in Art History

ww 12 DICK POLICH THE CONDUCTOR: DICK POLICH IN ART HISTORY BY DANIEL BELASCO > Louise Bourgeois’ 25 x 35 x 17 foot bronze Fountain at Polich Art Works, in collaboration with Bob Spring and Modern Art Foundry, 1999, Courtesy Dick Polich © Louise Bourgeois Estate / Licensed by VAGA, New York (cat. 40) ww TRANSFORMING METAL INTO ART 13 THE CONDUCTOR: DICK POLICH IN ART HISTORY 14 DICK POLICH Art foundry owner and metallurgist Dick Polich is one of those rare skeleton keys that unlocks the doors of modern and contemporary art. Since opening his first art foundry in the late 1960s, Polich has worked closely with the most significant artists of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. His foundries—Tallix (1970–2006), Polich of Polich’s energy and invention, Art Works (1995–2006), and Polich dedication to craft, and Tallix (2006–present)—have produced entrepreneurial acumen on the renowned artworks like Jeff Koons’ work of artists. As an art fabricator, gleaming stainless steel Rabbit (1986) and Polich remains behind the scenes, Louise Bourgeois’ imposing 30-foot tall his work subsumed into the careers spider Maman (2003), to name just two. of the artists. In recent years, They have also produced major public however, postmodernist artistic monuments, like the Korean War practices have discredited the myth Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC of the artist as solitary creator, and (1995), and the Leonardo da Vinci horse the public is increasingly curious in Milan (1999). His current business, to know how elaborately crafted Polich Tallix, is one of the largest and works of art are made.2 The best-regarded art foundries in the following essay, which corresponds world, a leader in the integration to the exhibition, interweaves a of technological and metallurgical history of Polich’s foundry know-how with the highest quality leadership with analysis of craftsmanship. -

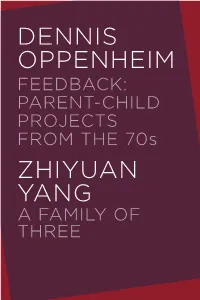

Zhiyuan Yang Dennis Oppenheim

DENNIS OPPENHEIM FEEDBACK: PARENT-CHILD PROJECTS FROM THE 70s ZHIYUAN YANG A FAMILY OF THREE DENNIS OPPENHEIM FEEDBACK: PARENT-CHILD PROJECTS FROM THE 70s ZHIYUAN YANG A FAMILY OF THREE SHIRLEY FITERMAN ART CENTER BOROUGH OF MANHATTAN COMMUNITY COLLEGE, CUNY IN HIS PIONEERING WORK OF THE LATE 1960s AND EARLY 70s , Dennis Oppenheim (1938-2011) went beyond the strictures of Minimalism to investigate and act in the actual world through explorations that engage both the landscape and the body. Perhaps best known for his Land Art works that transcended the confines of traditional sculpture, as well as the limits of the gallery context, Oppenheim’s performance works also pushed multiple boundaries.1 His artistic experimentation unfolded against a tumultuous historical backdrop that was branded by social and political unrest. The United States was enmeshed in a deeply unpopular war in Vietnam, one that provoked massive anti-war demonstrations through the early 70s. Concurrently, a widespread counterculture movement, led by the country’s youth, swept the nation. The turmoil continued with the Watergate scandal, which resulted in a vote by the House of Representatives to impeach then-President Richard Nixon, who resigned in summer 1974. The period was also defined by high unemployment, gas shortages, and rampant inflation. This same moment is marked artistically by a shift away from the strict tenets of Minimalism toward Post-Minimalism, which encompassed a more expansive approach to artmaking and a broad range of visual experimentation, including Process, Conceptual, and Performance Art. Leaving behind the specificity of the object, these practices presented art as encounters subject to physical and temporal conditions. -

Size, Scale and the Imaginary in the Work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim

Larger than life: size, scale and the imaginary in the work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim © Michael Albert Hedger A thesis in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Art History and Art Education UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES | Art & Design August 2014 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Hedger First name: Michael Other name/s: Albert Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: Ph.D. School: Art History and Education Faculty: Art & Design Title: Larger than life: size, scale and the imaginary in the work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Conventionally understood to be gigantic interventions in remote sites such as the deserts of Utah and Nevada, and packed with characteristics of "romance", "adventure" and "masculinity", Land Art (as this thesis shows) is a far more nuanced phenomenon. Through an examination of the work of three seminal artists: Michael Heizer (b. 1944), Dennis Oppenheim (1938-2011) and Walter De Maria (1935-2013), the thesis argues for an expanded reading of Land Art; one that recognizes the significance of size and scale but which takes a new view of these essential elements. This is achieved first by the introduction of the "imaginary" into the discourse on Land Art through two major literary texts, Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726) and Shelley's sonnet Ozymandias (1818)- works that, in addition to size and scale, negotiate presence and absence, the whimsical and fantastic, longevity and death, in ways that strongly resonate with Heizer, De Maria and especially Oppenheim. -

THE SHAPE-SHIFTER How Lynda Benglis Left the Bayou and Messed with with the Establishment

THE SHAPE-SHIFTER How Lynda Benglis left the bayou and messed with with the establishment BY M.H. MILLER Senior Editor You notice her face first. This is odd, because she’s nude, her body bronzed and oiled, with one wiry arm holding a large dou- ble-sided dildo between her legs. Her eyes aren’t even in play; a pair of white sunglasses covers them. The focus is really on her face, framed by an androgynous hairstyle that could have been cut and pasted from the cover of David Bowie’s Aladdin Sane. Her eyebrows are shaved. Her expression, to the extent that it’s readable, rests somewhere between a smirk and a grimace. Lynda Benglis was about to turn 33, and she wanted her nude self-portrait to run alongside a feature article about her by Robert Pincus-Witten in the November 1974 issue of Artforum. John Coplans, Artfo- rum’s editor, wouldn’t allow that, so her dealer at the time, Paula Cooper Gallery, took out an ad, which cost $2,436. Benglis paid for it, which involved a certain amount of panic. In the middle of October, as the issue was getting ready to go to the printer, she reached out to Cooper, frantically trying to track down collectors with outstanding payments so she could put the money toward the ad. “Everyone seems out to get me,” she wrote. Benglis’s ad might have been written off as a quirky footnote for an artist who would go on to become a pioneer of contemporary art in numerous guises, from video to sculpture to painting and beyond. -

Joel Shapiro: Sculpture and Drawings 1969-1972 to Be Exhibited at Craig F

CRAIG F. STARR GALLERY FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: CONTACT: Emily Larson + 1 (212) 570 1793 [email protected] Joel Shapiro: Sculpture and Drawings 1969-1972 To be exhibited at Craig F. Starr Gallery February 1 – March 23, 2013 NEW YORK – Craig F. Starr Gallery is pleased to announce an exhibition of early works by Joel Shapiro. On view from February 1 through March 23, the exhibition includes a selection of sculpture and drawings from 1969 through 1972. A fully illustrated catalogue accompanies the show with an essay by art historian Richard Shiff, Effie Marie Cain Regents Chair in Art at The University of Texas at Austin. Joel Shapiro began working in the late 1960s at a time when traditional notions of sculpture were being radically redefined by Minimalism and Conceptual Art. Between 1968 and 1973, he was interested in creating art that explored the passage of time and the accumulation of marks and materials. In his drawings, he investigated these ideas through the repeated gesture of mark-making with fingerprints on paper, and in sculpture, by amassing conical and spherical shapes which he hand formed in clay and porcelain. The works exhibited are primarily on loan from private collections across the country. Four sculptures and 13 drawings will be on view, including the large-scale Fingerprint Drawing (1969) from The Museum of Modern Art. Joel Shapiro (born 1941, New York City) received B.A. and M.A. degrees from New York University. Shapiro’s work has been the subject of more than 160 solo exhibitions and retrospectives internationally. He has executed over thirty commissions and publicly sited sculptures in major cities across the globe. -

Marlborough Gallery

Marlborough DENNIS OPPENHEIM 1938 — Born in Electric City, Washington 2011 — Died in New York, New York The artist lived and worked in New York, New York. Education 1965 — B.F.A., the School of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, California 1966 — M.F.A., Stanford University, Palo Alto, California Solo Exhibitions 2020 — Dennis Oppenheim, Galerie Mitterand, Paris, France 2019 — Feedback: Parent Child Projects from the 70s, Shirley Fiterman Art Center, The City University of New York, BMCC, New York, New York 2018 — Violations, 1971 — 1972, Marlborough Contemporary, New York, New York Broken Record Blues, Peder Lund, Oslo, Sweden 2016 — Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois Storm King Art Center, New Windsor, New York 2015 — Wooson Gallery, Daegu, Korea MAMCO, Geneva, Switzerland Halle Nord, Geneva, Switzerland 2014 — MOT International, London, United Kingdom Museo Magi'900, Pieve di Cento, Italy 2013 — Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, United Kingdom Museo Pecci Milano, Milan, Italy Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Yorkshire, United Kingdom Marlborough 2012 — Centro de Arte Palacio, Selected Works, Murcia, Spain Kunst Merano Arte, Merano, Italy Haines Gallery, San Francisco, California HaBeer, Beersheba, Israel 2011 — Musée d'Art moderne Saint-Etienne Metropole, Saint-Priest-en-Jarez, France Eaton Fine Arts, West Palm Beach, Florida Galerie Samuel Lallouz, Quebec, Canada The Carriage House, Gabarron Foundation, New York, New York 2010 — Thomas Solomon Gallery, Los Angeles, California Royale Projects, Indian Wells, California Buschlen Mowatt Galleries, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Galleria Fumagalli, Bergamo, Italy Gallerie d'arts Orler, Venice, Italy 2009 — Marta Museum, Herford, Germany Scolacium Park, Catanzaro, Italy Museo Marca, Catanzarto, Italy Eaton Fine Art, West Palm Beach, Florida Janos Gat Gallery, New York, New York 2008 — Ace Gallery, Beverly Hills, California 4 Culture Gallery, Seattle, Washington Edelman Arts, New York, New York D.O. -

Bibliography (Pdf/63Kb)

2006 • Connecting Worlds, Shikata Yukiko, NTT InterCommunication Center, Tokyo, Japan • Escritos de Artistas, Jorge Zahar, Jorge Zahar Editor Ltda., Rio de Janerio, Brazil • Ethics and the Visual Arts, E.A. King and G. Levin, Eds, Allworth Press, New York • Art Metropole: the Top 100, K. Scott and J. Shaughnesy, National Gallery of Art, Ottawa, Canada • Art and Video in the 70s, Silvana Editoriale Spa, Milan, Italy • Collection of the Fondation Cartier at MOT, Foil Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan 2005 • Slideshow: Projected images in Contemporary Art, Darcie Alexander, Baltimore Museum of Art, American University Presses, Pennsylvania • Odd Lots: Revisiting Gordon Matta-Clark‘s Fake Estates, Jeffrey Kastner, Sina Najafi and Frances Richard, Eds. Cabinet Books, New York • 40 years at the ICA, Johanna Plummer, Ed. Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, PA • Superstars: Warhol to Madonna, Sigrid Mittersteiner, Ed., Hatje Cantz Verlag, Germany • Comme le reve, le dessin, Centre Pompidou , Paris, France • Dennis Oppenheim: Project Drawings, Demetrio Paparoni, In Arco Books, Torino, Italy • La Poetica de lo Neutro, Victoria Combalia, Debolsillo, Barcelona, Spain • Domicile: prive/public, Lorand Hegyi, Somogy Editions d‘Art, Paris 2004 • The Context of Art/ The Art of Context, Seth Siegelaub, Marion Fricke and Roswitha Fricke, Navado Press, Trieste, Italy • Ana Mendieta Earth Body, Olga M. Vison, Hirshhorn Museum and Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany • Ready to Shoot Fernsehgalerie Gerry Schum, Ulrike Groos, Snoek Verlagsgesellschaft, Cologne, Germany • Art in Transit, Pallas Lombardi, Charlotte Area Transit System, Charlotte, North Carolina, U.S.A. • The Museum: Conditions and Spaces, Andrea Douglas, University of Virginia Art Museum, Charlottesville, Virginia, U.S.A. -

Minimal Art and Body Politics in New York City, 1961-1975 By

Minimal Art and Body Politics in New York City, 1961-1975 by Christopher M. Ketcham M.A. Art History, Tufts University, 2009 B.A. Art History, The George Washington University, 1998 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ARCHITECTURE: HISTORY AND THEORY OF ART AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER 2018 © 2018 Christopher M. Ketcham. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author:__________________________________________________ Department of Architecture August 10, 2018 Certified by:________________________________________________________ Caroline A. Jones Professor of the History of Art Thesis Supervisor Accepted by:_______________________________________________________ Professor Sheila Kennedy Chair of the Committee on Graduate Students Department of Architecture 2 Dissertation Committee: Caroline A. Jones, PhD Professor of the History of Art Massachusetts Institute of Technology Chair Mark Jarzombek, PhD Professor of the History and Theory of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Tom McDonough, PhD Associate Professor of Art History Binghamton University 3 4 Minimal Art and Body Politics in New York City, 1961-1975 by Christopher M. Ketcham Submitted to the Department of Architecture on August 10, 2018 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture: History and Theory of Art ABSTRACT In the mid-1960s, the artists who would come to occupy the center of minimal art’s canon were engaged with the city as a site and source of work.