A Station Formed at Tongala’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MELBOURNE - BARMAH VIA HEATHCOTE & SHEPPARTON Bus Time Schedule & Line Map

MELBOURNE - BARMAH VIA HEATHCOTE & SHEPPARTON bus time schedule & line map MELBOURNE - BARMAH VIA HE… Barmah View In Website Mode The MELBOURNE - BARMAH VIA HEATHCOTE & SHEPPARTON bus line (Barmah) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Barmah: 3:20 PM - 3:24 PM (2) Melbourne: 5:10 AM - 11:38 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest MELBOURNE - BARMAH VIA HEATHCOTE & SHEPPARTON bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next MELBOURNE - BARMAH VIA HEATHCOTE & SHEPPARTON bus arriving. Direction: Barmah MELBOURNE - BARMAH VIA HEATHCOTE & 25 stops SHEPPARTON bus Time Schedule VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Barmah Route Timetable: Sunday 5:00 PM Southern Cross Coach Terminal/Spencer St Monday 3:20 PM - 3:24 PM (Melbourne City) 201 Spencer Street, Docklands Tuesday 3:20 PM - 3:24 PM Coburg Ps/Bell St (Coburg) Wednesday 3:20 PM - 3:24 PM 81D Bell Street, Coburg Thursday 3:20 PM - 3:24 PM Camp Rd/Sydney Rd (Campbellƒeld) Friday 3:20 PM - 3:24 PM 1443 Sydney Road, Broadmeadows Saturday 5:00 PM Hadƒeld Park/High St (Wallan) 59 High Street, Wallan Hudson Park/Sydney St (Kilmore) 9 Sydney Street, Kilmore MELBOURNE - BARMAH VIA HEATHCOTE & SHEPPARTON bus Info Power St/High St (Pyalong) Direction: Barmah High Street, Pyalong Stops: 25 Trip Duration: 335 min General Store/Northern Hwy (Tooborac) Line Summary: Southern Cross Coach 5045 Northern Highway, Tooborac Terminal/Spencer St (Melbourne City), Coburg Ps/Bell St (Coburg), Camp Rd/Sydney Rd Jennings St/Northern Hwy (Heathcote) (Campbellƒeld), Hadƒeld Park/High St (Wallan), 68 High -

Edward M. Curr and the Tide of History

5. Decline and Fall In Recollections of Squatting in Victoria Edward M. Curr gives only a vague explanation for his leaving Victoria in February 1851, noting that he was ‘desirous of a change’ and wanted to travel through some of the countries ‘about which I had interested myself from boyhood’.1 There seems little doubt, however, that his father’s death three months earlier was a major catalyst in his decision; for a decade he had worked at the behest of his overbearing father, but was now free to pursue his own interests. Before he departed, arrangements were made regarding the runs he and his brothers had inherited. Richard Curr leased the southern squatting runs from his brothers and based himself at the Colbinabbin station. The northern runs (including Tongala) were let to a Mr Hodgson, although it appears that one or more of the younger Curr brothers might have assisted him with station management.2 Meanwhile, Edward, Charles and Walter departed the colony only a few months before the discovery of gold threw the pastoral industry into turmoil. Curr’s younger sister Florence recorded in a memoir that Richard established a home for his mother and younger siblings at Colbinabbin. As the closest station to Melbourne, Colbinabbin had occasionally been a winter residence for the wider Curr family. Richard’s principal challenge was maintaining his labour force, as the station was only 40 miles from the Bendigo goldfields. Eleven-year-old Florence later recalled that she had a marvellous time at Colbinabbin, blissfully unaffected by ‘the troubles of Richard in finding and still more in keeping shepherds’.3 The labour shortage is the principal reason why Richard, in consultation with his mother, decided to sell the squatting runs in 1852. -

To Download Your Copy of the Northern Regional Touring

ECHUCA FARMERS MARKET GIRGARRE PRODUCE & CRAFT Fresh produce MARKET Experience RUSHWORTH MARKET & farmers ROCHESTER TOWN MARKET fun for all History & market fun STANHOPE MONSTER GARAGE SALE Visit www.echucamoama.com for a full list of ages heritage market dates and times There is nothing quite as delicious as the fresh, crunchy taste of fruit and vegetables. BILLABONG RANCH TORRUMBARRY WEIR ROCHESTER SPORTS MUSEUM twistED Secure a unique piece of art and crafts and enjoy 30min from Echuca 20min from Echuca 2 Radcliffe St, Echuca 17min from Echuca live music – all while supporting local business! Glanville and Tehan Rd’s, Echuca Torrumbarry Weir Rd, Torrumbarry Rochester Railway Station, Northern Hwy 1300 984 823 www.twistedscience.com.au/echuca (03) 5483 5122 www.billabongranch.com.au (03) 5487 7221 Open Thursday to Sunday 10am-4pm, all public & Campaspe Shire’s small towns and villages host school holidays or by appointment regular farmers markets that have developed not- An award winning family tourist destination in the A great place to spend a few hours, regardless of The Torrumbarry Interpretive Centre features /rochestersportsmuseum to-be-missed reputations. heart of town. Experience a new way to play using your age! a photographic exhibition highlighting the your inner scientist. Choose from a range of activities, watch the importance of the loch systems to the Murray A collection of sporting memorabilia, which takes Long Paddock live show and enjoy an outback River, and to water conservation. you on a journey through a wide range of sports. experience like no other. Torrumbarry is also a popular spot for fishing, The collection includes items from Shane Warne, NATIONAL HOLDEN MUSEUM camping and all water sports, particularly skiing. -

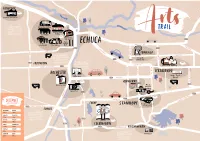

Map-Art-2021.Pdf

GUNBOWER MU R Gunbower Hotel Mural RA Y RIVER WHISTLE STOP GOUL Whistlestop Gallery BUR N RIVER TRAIL Customs House Port Atelier Gallery The Foundry Arts Space B400 River Redgum Port ECHUCA MURRAY VALLEY HWY Blacksmith Alton Gallery Wall HENDERSON ROAD ECHUCA ROAD B75 C359 MCKENZIE ROAD LOCKINGTONN ROAD JOHN ALLAN ROAD ECHUCA ROAD TONGALA FINLAY ROAD Tongala C351 C352 Street Art C342 LOCKINGTON GRAHAM ROAD C341 Town Hall Gallery MCEWEN ROAD WATSON ROAD PRAIRIE - ROCHESTER ROAD CURR ROAD KYABRAM BYRNESIDE ROAD ROCHESTER KYABRAM Iddles Lane Water Tank C362 WEBB ROAD Mural GIRGARRE C348 C354 GrainCorp Silos Many Sound Makers Walk Gallery Mural Park C347 Shaque-A C356 -Taque NORTHERN HWY WELCOME TO STANHOPE A300 MIDLAND HWY GIRGARRE ROAD DISTANCE RUSHWORTH TATURA ROAD From Echuca (Kms) COROP STANHOPE Fonterra Mural C357 C337 ELMORE - RAYWOOD ROAD & Art Space COLBINABBIN GIRGARRE ELMORE NORTHERN HWY 60Kms 41Kms ROCHESTER RUSHWORTH 27Kms 61Kms MIDLAND HWY C347 HEATHCOTE KYABRAM Silo Art 93Kms 38Kms B75 TONGALA TORRUMBARRY COLBINABBIN 26Kms 25Kms C345 BENDIGO MURCHISON ROAD RUSHWORTH GUNBOWER STANHOPE 41Kms 46Kms LOCKINGTON WHROO Art Depot 32Kms 68Kms ECHUCA ECHUCA ECHUCA ECHUCA ECHUCA KYABRAM Dairy & fruit growing town in the heart of the Goulburn Valley ‘food TOWNS bowl.’ TONGALA A vibrant community- TRAIL driven town undergoing an artistic facelift. ECHUCA Indulge all of the senses in the RUSHWORTH Steeped in rich goldfields jewel of Campaspe’s crown. history, the town boasts /thefoundryartsspace /customshousegalleryechuca altongalleryechuca.com /The-Port-Atelier /Port-of-Echuca-Blacksmithing historical buildings set emai.org.au/foundry-arts-space ROCHESTER Located on the banks of the Open Thursday – Monday Open Friday 10am – 3pm Open Thursday – Monday Open Friday – Monday Campaspe – a home of sport by a significant ironbark Open daily 10am – 4pm 10am – 4pm Saturday 10am – 1pm 10am – 4pm 10am – 3.30pm & growing arts scene. -

Lockington District Seniors Club Bamawm War Memorial Park

ISSUE #914 – April 30, 2021 Locky News Lockington’s Priceless Paper _ $ FREE Lockington District Bamawm War Memorial Park Unveiled. Seniors Club On Sunday, April 18 a wall depicting the site of Bamawm’s War Memorial Members who wish to attend the was unveiled by WGCDR John Glover RFD, and Margaret Davis, President 52nd anniversary of the club, of Bamawm CWA. Recreation Reserve President Garry Mundie welcomed to be held on Friday May 7th all present. Shire of Campaspe Mayor, Cr. Chrissy Weller expressed her at the Community Centre. pride in what the local community had done, then Tom Davis gave a history commencing at 1pm. of the site. ‘In 1911 3 acres were annexed off from the Recreation Reserve Please RSVP by May 1st for the RSL. In 1922 a memorial was dedicated followed by an evening To BEV BRERETON service in the hall. This was updated in 1995 to include the 2nd World War. Phone 5486 2331 The memorial wall was a vision by the Bamawm CWA’. John Glover in his dedication listed our local heroes whose names are listed on the memorial, detailing when they died, and where they are buried, if known. He said, ‘Since time immemorial women have borne the brunt of domestic tasks when their men have gone to war. No-where was this more apparent than in agricultural communities. Their greatest task, though, was managing the immeasurable grief when formal telegrams were delivered conveying the most dreadful of news: killed in action, missing believed killed or wounded in action. Many succumbed to the grief whilst others stoically tried to cope. -

UN/LOCODE) for Australia

United Nations Code for Trade and Transport Locations (UN/LOCODE) for Australia N.B. To check the official, current database of UN/LOCODEs see: https://www.unece.org/cefact/locode/service/location.html UN/LOCODE Location Name State Functionality Status Coordinatesi AU 2CO Tyabb VIC Road terminal; Recognised location 3815S 14511E AU 2IC Tarneit VIC Road terminal; Recognised location 3752S 14440E AU 2SN Yarrawarrah NSW Road terminal; Recognised location 3403S 15102E AU 2TO Wollert VIC Road terminal; Recognised location 3735S 14502E AU 2UA Woolooware NSW Road terminal; Recognised location 3403S 15108E AU 2VC Springvale South VIC Road terminal; Recognised location 3758S 14509E AU 2WS Brooklyn NSW Road terminal; Recognised location 3333S 15114E AU 32S Seaford SA Road terminal; Recognised location 3511S 13828E AU 3CI Rythdale VIC Road terminal; Recognised location 3808S 14526E AU 3CO Upwey VIC Road terminal; Recognised location 3754S 14520E AU 3WS Yowie Bay NSW Road terminal; Recognised location 3403S 15106E AU 4VC Strathewen VIC Road terminal; Recognised location 3733S 14516E AU 5CI Selby VIC Port; Multimodal function, ICD etc.; Recognised location 3755S 14523E AU 5CO Wantirna VIC Road terminal; Recognised location 3751S 14513E AU 5RC Werribee South VIC Road terminal; Recognised location 3756S 14443E AU 5TO Yan Yean VIC Road terminal; Recognised location 3734S 14506E AU 5WA Pilbara WA Road terminal; Recognised location 2115S 11818E AU 6CO Warrandyte VIC Road terminal; Recognised location 3745S 14514E AU 6DF West Hoxton NSW Road terminal; Recognised -

Barmah AD Effective 31/01/2021 Melbourne to Barmah Via Heathcote and Shepparton

Barmah AD Effective 31/01/2021 Melbourne to Barmah via Heathcote and Shepparton Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Service TRAIN COACH TRAIN COACH TRAIN COACH TRAIN Service Information VSƒç ∑ VSƒç ∑ VSƒç ∑ VSƒç SOUTHERN CROSS dep 12.36 15.20 16.07 17.00 18.36 17.00 18.36 Coburg – 15.47u – 17.20u – 17.20u – Campbellfield – 16.00u – 17.30u – 17.30u – Wallan Public Hall – 16.28 – 17.55 – 17.55 – Kilmore – 16.40 – 18.05 – 18.05 – Pyalong – 16.55 – 18.20 – 18.20 – Tooborac – 17.04 – 18.30 – 18.30 – HEATHCOTE (1) arr – 17.20 – 18.40 – 18.40 – HEATHCOTE (1) dep – 17.23 – 18.40T – 18.40 – Heathcote (2) – 17.24 – 18.42 – 18.42 – Colbinabbin – 17.52 – 19.10 – 19.10 – Rushworth – 18.07 – 19.25 – 19.25 – Stanhope – 18.22 – 19.40 – 19.40 – Girgarre – 18.27 – 19.45 – 19.45 – Kyabram – 18.42 – 20.00 – 20.00 – Merrigum – 18.57 – 20.15 – 20.15 – Tatura – 19.12 – 20.30 – 20.30 – Mooroopna Coach Stop – 19.27 – 20.45 – 20.45 – Mooroopna 15.06 – 18.50 – 21.05 – 21.05 SHEPPARTON arr 15.14 19.35 18.57 20.55 21.13 20.55 21.13 Change Service COACH COACH COACH COACH Service Information ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ SHEPPARTON dep 15.24 20.15 20.15 21.35 21.35 21.35 21.35 Shepparton (1) 15.26 20.17 20.17 21.37 21.37 21.37 21.37 Goulburn Valley Hospital 15.29 – – – – – – Zeerust 15.42 20.28 20.28 21.48 21.48 21.48 21.48 Bunbartha 15.48 20.34 20.34 21.54 21.54 21.54 21.54 Kaarimba 15.54 20.41 20.41 22.01 22.01 22.01 22.01 Nathalia 16.04 20.52 20.52 22.12 22.12 22.12 22.12 Picola 16.14 21.06 21.06 22.26 22.26 22.26 22.26 BARMAH arr 16.24 21.15 21.15 22.35 22.35 22.35 22.35 ƒ – First Class / ç – Catering / ∑ – Wheelchair accessible / u – Pick up only / T – Connects at Heathcote to Melbourne Airport / VS – Via Seymour / Coach services shown in red / £ Reservations required Altered timetables may apply on public holidays. -

[email protected] - Phone: 58 561 230 - Fax: 58 561 940 Website

Email: [email protected] - Phone: 58 561 230 - Fax: 58 561 940 Website: www.rushworthp-12.vic.edu.au Issue No. 4 24 March 2017 What a wonderful community celebration we took part in this week…. More inside. Be Respectful, Be Responsible, Be Resilient PAGE 2 RUSHWORTH P-12 COLLEGE NEWSLETTER ISSUE 4 27 28 29 30 31 CFA Excursion Family/Student/ Family/Student/ Teacher interviews Teacher interviews School banking day 4.00 - 8.00pm 8.30am - 2.00pm NO SCHEDULED CLASSES Term 1 finishes Early dismissal 2.30 pm 17 18 18 20 21 EASTER MONDAY TERM 2 COMMENCES School banking day Newsletter home PUBLIC HOLIDAY Staff Learning Day - STUDENT FREE DAY 24 25 26 27 28 College ANZAC ANZAC DAY School banking day ceremony 2.30pm PUBLIC HOLIDAY College Council 7.00pm 1 2 3 4 5 P-12 Assembly 9.00am School banking day P-12 College Athletics Primary Athletics Carnival Carnival (Year 3-6) Shepparton Newsletter home 8 9 10 11 12 NAPLAN NAPLAN NAPLAN P-12 Assembly 9.00am School banking day Be Respectful, Be Responsible, Be Resilient ISSUE 4 RUSHWORTH P-12 COLLEGE NEWSLETTER PAGE 3 News from the Principal…. At last year’s presentation night, I mentioned how proud I was to be the principal of Rushworth P-12 College. This is mostly due to it being such a great school with wonderful student, staff, family and community members making it a place full of promise. There is another reason, however, why I feel so proud to be a teacher and school leader at Rushworth. -

Community-Newsletter-July-2020.Pdf

In this issue Echuca Riverfront Campaspe Times Newsletter redevelopment 2 Waste news 3 July 2020 Project update - roads 4 Love where you live – Colbinabbin Silo Art 5 Facing challenges head on Rabbit control program 5 With COVID-19 restrictions continuing of what’s to occur and timeframes. The to impact services across Campaspe, information also links back to interactive Kyabram Drainage Basin it has been pleasing to see our mapping on the home page, so you can project 6 community following government see what is planned near you. Campaspe Animal Shelter directions and supporting each other. One of the most rewarding aspects of upgrades 6 I encourage the community to keep my role as Mayor is the conferring and Parking in Campaspe 7 up to date with changes as they are welcoming of new Australians to the announced and hopefully, we can soon Service profile – Library Campaspe community. We recently see services returning to some level of Services 8 celebrated 11 new Australian citizens normality. in a modified manner. With gathering Campaspe Libraries responded to the numbers restricted, the citizenship limitations of the number of people ceremony was recorded so friends and Get social and allowed in each building by expanding relatives did not have to miss out on the stay updated their online presence with a multitude of momentous occasion. Congratulations free resources available and continuing to all our new Australian Citizens and @CampaspeShireCouncil to be available. You can read more their families. about this on page eight. @campaspeshire Winter is in full swing and with the wet #campaspeshire As the financial year ended, many weather upon us, please take care on projects both large and small were the roads and drive to conditions. -

Victorian Heritage Database Place Details - 2/10/2021 COLBINABBIN HOMESTEAD

Victorian Heritage Database place details - 2/10/2021 COLBINABBIN HOMESTEAD Location: 87 OSMENT ROAD COLBINABBIN, Campaspe Shire Victorian Heritage Register (VHR) Number: H1730 Listing Authority: VHR Extent of Registration: NOTICE OF REGISTRATION As Executive Director for the purpose of the Heritage Act 1995, I give notice under section 46 that the Victorian Heritage Register is amended by including the Heritage Register Number 1730 in the categories described as a Heritage Place, Archaeological Place: Colbinabbin Homestead, Osment Road, Colbinabbin, Campaspe Shire Council. EXTENT: 1. All of the buildings and features marked as follows on Diagrams 1730a, 1730b & 1730c held by the Executive Director. B1 House B2 Bakehouse B3 Woolshed F1 Cattle Dip F2 Cemetery 1 2. All the land marked L1, L2 & L3 on Diagrams 1730a, 1730b & 1730c held by the Executive Director. 3. All the archaeological remains on the land on Diagrams 1730a, 1730b & 1730c. Dated 20 October 2006 RAY TONKIN Executive Director Victoria Government Gazette G 43 26 October 2006 2305] Statement of Significance: Colbinabbin Homestead, an Italianate style single storey solid brick and stucco house with a cast iron a verandah with concave galvanised iron roof, was designed by Bendigo based architect, Robert Alexander Love, was and built for John Irving Winter in 1867. The Irving Winter Family owned large pastoral interests throughout Victoria , New South Wales and Queensland which were established with the proceeds of gold discovered on their land near Ballarat. The Colbinabbin run was established by William Curr in 1843 and was bought by John Winter for his four sons in 1857. John [Jock] Winter, the son of a blacksmith, arrived in Australia with his family from Scotland in 1841 and settled near Ballarat. -

05 Shire of Campaspe.Pdf 4.03 Mb

Flood Mitigation Infrastructure Submission Shire of Campaspe – Inquiry into Flood Mitigation Infrastructure in Victoria - July 2011 Table of Contents SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................2 SECTION 2: THE MUNICIPAL AREA ..............................................................................3 SECTION 3: FLOOD HISTORY ......................................................................................6 3.1 SEPTEMBER 2010 ........................................................................................................ 7 3.2 NOVEMBER /D ECEMBER 2010........................................................................................ 8 3.3 JANUARY 2011........................................................................................................... 10 3.4 FEBRUARY 2011 ....................................................................................................... 11 SECTION 4: TERMS OF REFERENCE ........................................................................... 12 SECTION 4.1: BEST PRACTICE FLOOD MITIGATION AND MONITORING INFRASTRUCTURE 13 4.1.1 FLOOD MITIGATION ................................................................................................. 13 4.1.2 FLOOD MONITORING INFRASTRUCTURE .................................................................... 20 RESPONSE .......................................................................................................................... 22 SECTION 4.2: MANAGEMENT -

Directory Health & Community Services in Campaspe

DIRECTORY Health & Community Services in Campaspe Directory of Health and Community Services in Campaspe This directory includes service contact details and service descriptions to help you find the services you need. The directory provides a list of publicly funded providers – for private providers please refer to your local telephone directories. Acknowledgements This directory is an initiative of the Campaspe Primary Care Partnership (PCP), funded by the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services. This directory was developed with input from the Campaspe PCP Service Integration Steering Committee. For further service information go to www.nhsd.com.au which provides a nation-wide directory of services accessible to both consumers and professionals. For e-secure messaging www.connectingcare.com supports secure transfer of referrals and other messages whilst complying with all health information privacy legislation. The Better Heath Channel is a reliable health information access point for consumers, and professionals to use at www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au. Please note that fees apply to some services - check with your service provider. Produced November 2019. Acknowledgement of Country Campaspe PCP respectfully acknowledges the traditional Aboriginal owners of country and pay our respects to them, their living culture and Elders past, present and future. The Campaspe Shire Council is the traditional lands of the Dja Dja Wurrung, Taungurung and Yorta Yorta Peoples. Index ABORIGINAL SERVICES 2 - 3 AGED CARE SERVICES 4 - 6 ALCOHOL