WIDER Working Paper 2021/21-Can Information Dissemination Reduce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11536/SIC-MNR/2018 Date: 22-01-2021

TELANGANA STATE INFORMATION COMMISSION (Under Right to Information Act, 2005) Samachara Hakku Bhavan, D.No.5-4-399, ‘4’ Storied Commercial Complex, Housing Board Building, Mojam Jahi Market, Hyderabad – 500 001. Phone Nos: 040-24740666 (O); 040-24740592(F) N O T I C E Appeal No.11536/SIC-MNR/2018 Date: 22-01-2021 Ref:- 1. 6(1) Application dated 17-03-2018 filed before the Public Information Officer. 2. 19(1) 1st Appeal dated 29-05-2018 filed before the 1st Appellate Authority. &&& Whereas Ms. V. Uma Parvathi has filed an appeal U/s 19(3) of the RTI Act, 2005 before this Commission against the Public Authority; and whereas the said appeal is posted for hearing on the 17th Day of February, 2021 at 10.30 AM. A. The Respondents are hereby directed to appear in person before the Commission at 10.30 AM on 17th Day of February, 2021 along with written affidavits containing: (i) The action taken (point wise) on 6(1) application / 19(1) appeal. (ii) Copies of information furnished to the appellant and proof of dispatch / receipt / acknowledgement by the appellant. (iii) Point wise counter on the 2nd appeal along with enclosed affidavit duly filled in all respects; and (iv) The Respondent shall produce a copy of the 4(1) (b) data for the perusal of State Information Commission. B. The Appellant to attend the hearing on the said date and time along with affidavits containing the: (i) Points for which information is not furnished; and (ii). Points for which information furnished is unsatisfactory / incorrect / false giving complete justification in support of his claim. -

4754/SIC-SK/2019 Date: 11-02-2021

Telangana State Information Commission (Under Right to Information Act, 2005) D.No.5-4-399, Samachara Hakku Bhavan (Old ACB Building), Mojam-jahi-Market, Hyderabad – 500001. Phone: 24740155 Fax: 247405928 Complaint No: 4754/SIC-SK/2019 Date: 11-02-2021 Complainant : Sri. B. Narayana, Hyderabad. Respondent : Public Information Officer (U/RTI Act, 2005) O/o the Tahsildar, Makthal, Kamath Narva Village, Mahabubnagar District. Order Sri. B. Narayana, Hyderabad has filed a Complaint dated: 22-04-2019 which was received by this Commission on 23-04-2019 for not complying the Commission order in appeal No: 10704/CIC-(peshi-2)/2018 dated: 11-03-2019 and for not getting the information sought by him through his 6(1) application dated: 16-07-2017 from the Public Information Officer / O/o the Tahsildar, Makthal, Kamath Narva Village, Mahabubnagar District. In view of the above, the Complaint may be taken on file and Notices issued to both the parties for hearing on 11-02-2021 at 10.30 A.M. The case is called on 11-02-2021. The complainant is present and stated that the PIO has not furnished the information. The PIO / Sri. M. Kalappa, Deputy Tahsildar, Makthal Mandal, Narayanpet District is present and stated that the available information was furnished to the complainant vide letter No: A/2128/2017 dated: 22-07-2017. Heard both the parties and perused the material papers available on record. After a prolonged discussion, the Commission directs the PIO to allow the complainantTSIC for verification of records on a mutually fixed date & time by issuing prior intimation to the complainant to enable him to obtain the required information and to report compliance to the Commission. -

Pg. 1 M.No.: 9963674099

State: Telangana District Indic Weav Techni ate, if e/s que of Name of it is practi produc Name of Photo S. Awardee/ Award GI ced in t Product Complete address, M.No. Photo of exclusive s of N weaver/ received, prod the weavin descripti e.mail Weaver handloom prod o. Co-op Society if any uct handl g on products ucts etc. oom produ ct The base of fabric is plain. Patterns are transfor med on Padma Pochampalli to yarns Shri – 2011 Tie & dye raw Puttapaka, in silk fabric Dist: Nalgonda Yarn different Shri Gajam National Plain Telangana Tie & colours Govardhana Award- Pochampalli weav Enclo 1. M.No.: Nalgonda yes Dye by tying 9963674099 1983 Tie & dye e sed (Ikat) (resisting) e.mail: Cotton Bed and [email protected] UNESCO sheet dyeing m Award- the 2006 exposed area repeate dly before weaving. pg. 1 The base of fabric is plain. Patterns are transfor med on to yarns in PadmasriA different Office address: H.No.11-7- ward- colours 140/3 A, Huda Colony 2013, by tying Saroornagar, Hyderabad (resisting) Traditional Yarn Sant Kabir Plain and Permanent address: TeliaRumalSaree Tie & Shri Award- weav Enclo dyeing 2. Puttapaka, Nalgonda with Vegetable yes Dye GajamAnjaiah 2010 e sed the Dist: Nalgonda Colours (Ikat) exposed Telangana National area M.No.: 944041683 award- repeate e.mail:kaladhanalakshmi 1987 dly @gmail.com before weaving. Gingelly oil is used to make the fabric soft. Patterns are transfor med on to yarns in Puttapaka, different Dist: Nalgonda colours Yarn Telangana Plain by tying National Tie & Shri Pochampalli weav Enclo (resisting) 3. -

32-Narayanpet.Pdf

GOVERNMENT OF TELANGANA ABSTRACT Child Protection - Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 (Central Act No.2 of 2016) - Constitution of Child Welfare Committee in the - Narayanpet District - Notification - lssued. DEPARTMENT FOR WOMEN, CHILDREN, DISABLED AND SENIOR ClTrzENS (SCHEMES-r) G.O.Ms.No.32, Dated:05.02.2021 . Read the followinq: 1 . The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 (Act No.2 of 2016). 2. G.O.Rt.No.73, Dept., forWCD&SC Dated: 29.10.2019. o-O-o ORDER: ln the G.O.2nd read above, the Selection Committee has been constituted under the Chairmanship of Dr.Justice Motilal B.Naik Judge (Retired), High Court, Hyderabad for selection of Chairperson/Members of Child Welfare Committee and Social Workers of Juvenile Justice Boards as required under Rule 87 of Model Rules,2016 under JJ(CPC) Act,2015. The Selection Commiftee has submitted its recommendations to Government based on the process laid down as per rule BB(4) of JJ Modal Rules, 2016. 2. Government after careful examination of the said recommendation and in order to implement the provisions of the Juvenile Jusilce (cpc) Act, 2015 hereby constitutes the child welfare committee for the Districts in the State with respective district as their jurisdiction. 3. Accordingly, the following Notification shall be published in the Extra_ ordinary issue of the Telangana State Gazette on 05.02.2021: NOTIFICATI ON ln exercise of the powers conferred under sub-section 1 of section 27 of Juvenile Justice (cPC) Act, 201S(central Act 2 ot 2016), Government hereby constitutes the child welfare committee for Narayanpet tjistrict as mentioned in the table below for a period of (3) years from the'date of issue of notification for exercising the powers and to discharge the duties conferred on such committee in relation to children in need of care and protection under the Act. -

CGR Newsletter July 2020.Pdf

CGR’S CNN NATURE NEWS Vol. 2, No.10 July 2020 Editorial Health, education, justice and a wholesome environment are the most important sustainable development goals. Progress in these goals will positively impact the other goals. As time moves by, any society, or a nation, needs periodical introspection, new thought of reform, restructuring, and paradigm shifts in critical development sectors. And the thought must come from a collective conscience of the wider horizon of society. The relative slow down of the rush of life due to the prevailing Covid pandemic has provided a space for contemplation. Given the scope and need, CGR has launched two competitions seeking essays and articles with suggestions to improve - rural primary health, and environmental laws. And this month we are launching a competition on school education. The best articles will be honoured and selected articles will be compiled into vision documents and will be shared with the concerned policymakers and made available in the public domain. Digital earth reel is another ongoing short films competition, Inside… which received a huge response nationally. We Webinar on village biodiversity 2 wish all these competitions reach a large number World Environment Day 3 Webinar with singers 4 of people to participate. Webinar on green village 5 Webinar on green village 5 In June 2020, CGR has intensively conducted Webinar on green village 5 webinars and began its annual plantation activity Webinar on green village 7 th on 20 June 2020 by planting saplings in 60 Webinar on youth for environment 8 villages. This year CGR has made an MoU with Green village plantation 9 Mahabubnagar district administration to take up MoU on Palamuru Vanachaitanya Yatra 16 Palamuru Vanachaitanya Yatra - massive tree Digital Earth Reel 17 plantation all over the district through Cmopetetion on Rural Primary Health 18 involvement of children from government schools. -

11536/SIC-MNR/2018 Date: - 17-02-2021

Telangana State Information Commission (Under Right to Information Act, 2005) D.No.5-4-399, Samachara Hakku Bhavan (Old ACB Building), Mojam-jahi-Market, Hyderabad – 500 001 Phone: 24740666 Fax: 24740592 Appeal No:11536/SIC-MNR/2018 Date: - 17-02-2021 Appellant : Ms.V.Uma Parvathi, H.No.20-43, Nakrekal, Nalgonda District. Respondents : Public Information Officer (U/RTI Act, 2005) The Medical Officer, PHC, Kotakonda, Narayanpet District. First Appellate Authority (U/RTI Act, 2005) The DM&HO., Narayanpet District. Order Ms. V. Uma Parvathi has filed second appeal dated 08-08-2018 which was received by this Commission on 09-08-2018 for not getting the information sought by him from the Public Information Officer/ The Medical Officer, PHC, Kotakonda, Narayanpet, District and the First Appellate Authority/ The DM&HO., Narayanpet District. The brief facts of the case as per the appeal and other records received along with it are that the appellant herein filed an application dated 17-03-2018 before the Public Information Officer requesting to furnish the information under Sec. 6(1) of the RTI Act,TSIC 2005 on the following points mentioned: Stating that the appellant did not get any response from the Public Information Officer, she filed 1st appeal dated 29-05-2018 before the First Appellate Authority requesting him to furnish the information sought by her u/s 19(1) of the RTI Act, 2005. Stating that the appellant did not get any response from the First Appellate Authority, she preferred this 2nd appeal before this Commission requesting to arrange to furnish the information sought by her u/s 19(3) of the RTI Act, 2005. -

Forest-Dept-Contact-List

A. ESSENTIAL SERVICES AIRLINE SERVICES PARTICULARS CONTACT NOS Rajiv Gandhi International Airport 040 – 66764000 (O) Toll Free 66546370 (O) 1800-102-2008 (O) Air India 040 – 23389711/12 (O) 1800-180-1407 (O) Indigo Airlines 09212783838 (M) Jet Airways 040 – 39893333 (O) 1800-22-5522 (O) Go Air 09223222111 (M) 040 – 66546370 (O) Spice Jet 09654003333 (M) 040 – 27004793/94 (O) T.S.R.T.C / TOURISM SERVICES MGBS – Enquiry 08330933537 (M) 040 – 24614406 (O) MGBS – Reservation 040 – 24613955 (O) Dilsukhnagar - Enquiry & Reservation 040 – 30102829 (O) Koti Bus Station 040 – 65577774 (O) JBS Enquiry & Reservation 040 – 27802203 (O) T.S. Tourism, Himayathnagar 040 - 23262151 (O) Garuda Tourism 09866128399 (M) India Tourism 040-23409199 & 200 (O) Charminar Bus Station 09959226157 (M) 040 – 23443317 (O) Secunderabad Bus Station 9959226154 (M) 040 – 23443399 (O) Secretariat Bus Station 040-23236656 (O) Medchal Bus Station 9959226158 (M) Sanathnagar Bus Station 9959226159 (M) BLOOD BANKS & EYE BANKS NIMS Blood Bank, Punjagutta 040 – 23489000 (O) Gandhi Hospital 040 – 27505566 (O) 27722222 (O) St. Theresas Blood Bank 040 – 23802255 (O) Chiranjeevi Blood Bank & Eye Bank 040 – 23555005 (O) Lions Club Blood & Eye Bank 040 – 23226624 (O) 27802124 (O) L.V. Prasad Eye Institute 040 – 30612345 (O) Kishore Chand Chordia Eye Centre 040 – 24610995 (O) Sarojini Devi Eye Hospital 040 – 23317274 (O) CAB SERVICES Orange Cabs 040 – 44454647 (O) Meru Cabs 040 – 40520000(O) Dot Cabs 040 – 24242424 (O) ~ 1 ~ PARTICULARS CONTACT NOS Yellow Cabs 040 – 46464646 (O) City -

Dôfcet*Cuiafc-G)Tt. V a L I 1938

Spume»*« ©mtfemtce pi^tijoùiat CîpiBCOpnl (CljUfClr 'T'i ■'< rj)irtcentl) Jlnnwal Cession ìH4AK w Dôfcet*cUiafc-g)tt. v a l i 1938. THE ANNUAL REPORTS AND MINUTES of the THIRTEENTH ANNUAL SESSION of the Hyderabad Wcn?etj’s Cotjferepce of the METHODIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH Held in Hyderabad, Deccan. Nov. 23 to 28, 1938. Printed at Moses & Co., Secunderabad. 1938. ROLL OF MEMBERS ON THE FIELD. "Na m e . A d d r e ss . Pickett, Mrs. J. W. Bombay. Christdas, Miss C. Vikarabad. öoleman, Miss M. Hyderabad. David, Mrs. O. Narayanpet. DeLima, Miss K Hyderabad. Ernsberger, Mrs. M. C. ... Bidar. Garden. Mrs. G. B. Hyderabad. Harrod, Miss A. Tandur. Huibregtse, Miss M. Bidar. Jacob, Mrs. J. Ranjol. Low, Miss N. M. Hyderabad. Luke, Miss A. Bidar. McEldowney, Mrs. J. E. Hyderabad. Morgan, Miss Mabel Vikarabad, Morgan, Miss Margaret. Hyderabad. Partridge, Miss R A. ... Zaheerabad. Patterson, Mrs. J. Vikarabad. Ross, Mrs. M. D. Bidar. Shanthappa, Mrs. E., l .m .p . Bidar. Simonds, Miss M. Tandur. Sunderam, Mrs. G. Hyderabad. Webb, Miss G. Hyderabad. Woodbridge, Miss L. V ikarabad. ROLL OF ASSOCIATE MEMBERS. Andrew, Miss P. ... ... ... ... Hyderabad. ROLL OF MEMBERS ON LEAVE. Metsker, Miss K. Wells, Miss E. J. RETIRED MEMBERS. Mrs. M. Tindale. Mrs. S. Parker. Mrs. K. E. Anderson. Miss G. Patterson. Miss M. Smith. WOMEN’S APPOINTMENTS. BIDAR DISTRICT. Bidar Girls’ School: Principal, until June 1st..................................................Mrs. Ernsberger. Principal, after June 1st................................................ Miss Ada Luke. Superintendent of the Hostel, and Headmistress of the Primary Department, after June 1st.................. Miss Minnie Huibregtse. On Language Study, until June 1st Miss Minnie Huibregtse. -

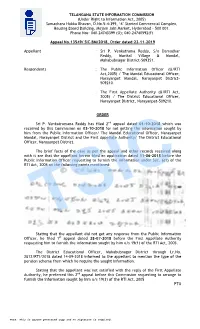

Under Right to Information Act, 2005

TELANGANA STATE INFORMATION COMMISSION (Under Right to Information Act, 2005) Samachara Hakku Bhavan, D.No.5-4-399, ‘4’ Storied Commercial Complex, Housing Board Building, Mojam Jahi Market, Hyderabad – 500 001. Phone Nos: 040-24743399 (O); 040-24740592(F) Appeal No.13549/ SIC-BM/2018, Order dated:22-11-2019 Appellant : Sri P. Venkatrama Reddy, S/o Damodhar Reddy, Marikal Village & Mandal, Mahabubnagar District-509351. Respondents : The Public Information Officer (U/RTI Act,2005) / The Mandal Educational Officer, Narayanpet Mandal, Narayanpet District- 509210. : The First Appellate Authority (U/RTI Act, 2005) / The District Educational Officer, Narayanpet District, Narayanpet-509210. ORDER Sri P. Venkatramana Reddy has filed 2nd appeal dated 01-10-2018 which was received by this Commission on 03-10-2018 for not getting the information sought by him from the Public Information Officer/ The Mandal Educational Officer, Narayanpet Mandal, Narayanpet District and the First Appellate Authority/ The District Educational Officer, Narayanpet District. The brief facts of the case as per the appeal and other records received along with it are that the appellant herein filed an application dated 11-06-2018 before the Public Information Officer requesting to furnish the information under Sec. 6(1) of the RTI Act, 2005TSIC on the following points mentioned: Stating that the appellant did not get any response from the Public Information Officer, he filed 1st appeal dated 28-07-2018 before the First Appellate Authority requesting him to furnish the information sought by him u/s 19(1) of the RTI Act, 2005. The District Educational Officer, Mahabubnagar District through Lr.No. -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1984, 25/01/2021

Trade Marks Journal No: 1984, 25/01/2021 Reg. No. TECH/47-714/MBI/2000 Registered as News Paper p`kaSana : Baart sarkar vyaapar icanh rijasT/I esa.ema.raoD eMTa^p ihla ko pasa paosT Aa^ifsa ko pasa vaDalaa mauMba[- 400037 durBaaYa : 022 24101144 ,24101177 ,24148251 ,24112211. Published by: The Government of India, Office of The Trade Marks Registry, Baudhik Sampada Bhavan (I.P. Bhavan) Near Antop Hill, Head Post Office, S.M. Road, Mumbai-400037. Tel: 022 24101144, 24101177, 24148251, 24112211. 1 Trade Marks Journal No: 1984, 25/01/2021 Anauk/maiNaka INDEX AiQakairk saucanaaeM Official Notes vyaapar icanh rijasT/IkrNa kayaa-laya ka AiQakar xao~ Jurisdiction of Offices of the Trade Marks Registry sauiBannata ko baaro maoM rijaYT/ar kao p`arMiBak salaah AaoOr Kaoja ko ilayao inavaodna Preliminary advice by Registrar as to distinctiveness and request for search saMbaw icanh Associated Marks ivaraoQa Opposition ivaiQak p`maaNa p`~ iT.ema.46 pr AnauraoQa Legal Certificate/ Request on Form TM-46 k^apIra[T p`maaNa p`~ Copyright Certificate t%kala kaya- Operation Tatkal saava-jainak saucanaaeM Public Notices iva&aipt Aavaodna Applications advertised class-wise: 2 Trade Marks Journal No: 1984, 25/01/2021 vagavagavaga-vaga--- /// Class - 1 11-92 vagavagavaga-vaga--- /// Class - 2 92-125 vagavagavaga-vaga--- /// Class - 3 126-407 vagavagavaga-vaga--- /// Class - 4 408-448 vagavagavaga-vaga--- / Class - 5 449-1224 vagavagavaga-vaga--- /// Class - 6 1225-1307 vagavagavaga-vaga--- /// Class - 7 1308-1423 vagavagavaga-vaga--- /// Class - 8 1424-1453 vagavagavaga-vaga--- -

Cnn Cgr's Nature News

CGR’S CNN NATURE NEWS Vol. 2, No. 1 October 2019 Editorial It is the season of Seetaphal, the custard apple. These are extensively found in rural wilderness and villages relish it on the trees or ripen it and eat. Going out in the village for seetaphal in villages wilderness is one of memory of most who comes from villages. The flesh is fragrant and sweet, creamy white through light yellow, and resembles and tastes like custard hence we call it widely as custard apple in English. It is also known as sugar-apple, or sweetsop. The plant (Annona squamosa) is native of the tropical Americas and West Indies. The Spanish traders introduced it to Asia. It is one of the important nutritious seasonal diets in our country and other countries which is high in energy, an Patience is bitter, but its fruit is sweet- excellent source of vitamin C and Jeen Jacques Rousseau manganese, a good source of thiamine and vitamin B6, and provides vitamin B2, Inside… B B , B , iron, magnesium, phosphorus 3 5 9 JC Bose Memorial Gardens 2 and potassium in fair quantities. Green village plantation 3 Climate Emergency Meet 5 Due to expansion of farming and other Training on Earth leadership 7 pressures this fruit species is declining in Other Updates 8 a rapid manner. We need to leaves the parts of nature to protect this species which enriches the seasonal diet of village. 1 JC Bose Memorial Gardens As part of Krishna-Bheema Vanachaitanya Yatra massive tree plantation drive in Narayanpet district, CGR has initiated JC Bose Memorial Gardens Programme. -

India 2019 Human Rights Report

INDIA 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY India is a multiparty, federal, parliamentary democracy with a bicameral legislature. The president, elected by an electoral college composed of the state assemblies and parliament, is the head of state, and the prime minister is the head of government. Under the constitution, the country’s 28 states and nine union territories have a high degree of autonomy and have primary responsibility for law and order. Electors chose President Ram Nath Kovind in 2017 to serve a five-year term, and Narendra Modi became prime minister for the second time following the victory of the National Democratic Alliance coalition led by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in the 2019 general election. Observers considered the parliamentary elections, which included more than 600 million voters, to be free and fair, although with isolated instances of violence. The states and union territories have primary responsibility for maintaining law and order, with policy oversight from the central government. Police are under state jurisdiction. The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) controls most paramilitary forces, the internal intelligence bureaus and national law enforcement agencies, and provides training for senior officials from state police forces. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. Significant human rights issues included: unlawful and arbitrary killings, including extrajudicial killings perpetrated by police; torture by prison officials; arbitrary arrest and detention by government