Exploring the Role of Humor and Music in Radio Advertisement: a Quasi-Experimental Study on Domestic Tourist Attitudes and Behav

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![But[T]... the Federal Communications Commission Will Not Let](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1148/but-t-the-federal-communications-commission-will-not-let-1501148.webp)

But[T]... the Federal Communications Commission Will Not Let

WLR45-2_QUALE_EIC2_SAC_12_16_08_CQ_FINAL_REVIEW 12/18/2008 11:35:12 AM HEAR AN [EXPLETIVE], THERE AN [EXPLETIVE], BUT[T] . THE FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION WILL NOT LET YOU SAY AN [EXPLETIVE] COURTNEY LIVINGSTON QUALE∗ I. AN OVERVIEW Broadcast television and broadcast radio2 are integral parts of American society. So integral, in fact, that often these mediums are taken for granted. To many Americans, broadcast television and broadcast radio are one of the few free things left in life. Anyone who owns a ten dollar radio or a fifty dollar television can watch their favorite new episode of Grey’s Anatomy, Sixty Minutes, or Lost and listen to their favorite songs or commentary on KNRK, Z100, or NPR. Because broadcast television and broadcast radio are typically taken for granted, hardly anyone questions the conditions that a regulatory governmental agency places upon the organizations that ∗ J.D. Willamette University College of Law, May 2008; B.S. University of Miami, May 2005. I would like to thank those who not only have helped me with this article, but also those who have helped me reach this point in my life—a point at which my thoughts are of a publishable quality. I thank you all most kindly. From the University of Miami I want to thank Professors S.L. Harrison and Robert Stahr Hosmon, who initially cultivated any writing talent I may have. Also from Miami, I would like to thank Professors Cynthia Cordes and Danny Paskin, who have unabashedly encouraged me over years. From Willamette University College of Law I want to thank Professor Ed Harri and Rachael Rogers, again for helping me learn how to write, think, and analyze. -

INTRODUCTION Communication Is Always One of the Most Important

INTRODUCTION Communication is always one of the most important and vital strategic areas of an organization's success. You can have the best or most innovative products or services, but if your internal and external communications are weak, then the demand for your products or services raises a personal flag of concern. When communicating the value of your products or services, you want to focus on how they will benefit your clients. When planning your strategy for Integrated Marketing Communication or IMC, you want to have dialogue with your customers by inviting interaction through the coordinated efforts of content, timing and delivery of your products or services. By ensuring direction, clarity, consistency, timing and appearance of your messages, conveyed to your targeted audience, these factors will help avoid any confusion about the benefits of your brand, through the connection of instant product recognition. When looking at your marketing mix, you're examining price, distribution, advertising and promotion, along with customer service. Integrated marketing communication is part of that marketing mix included in your marketing plan. IMC strategies define your target audience, establishes objectives and budgets, analyzes any social, competitive, cultural or technological issues, and conducts research to evaluate the effectiveness of your promotional strategies. If companies are ethically planning, communicating, and following industry guidelines, they will most likely earn the trust of their customers and target audience. There are five basic tools of integrated marketing communication: Advertising, Sales Promotion, Public Relations, Direct Marketing and Personal Selling. ADVERTISING Advertising is a form of communication used to persuade an audience (viewers, readers or listeners) to take some action with respect to products, ideas, or services. -

Successful Marketing Strategies Employed by Traditional AM/FM Radio Stations Shaquilla Nicole Smith Walden University

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2018 Successful Marketing Strategies Employed by Traditional AM/FM Radio Stations Shaquilla Nicole Smith Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, and the Marketing Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Management and Technology This is to certify that the doctoral study by Shaquilla N. Smith has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Michael Lavelle, Committee Chairperson, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. Timothy Malone, Committee Member, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. Rocky Dwyer, University Reviewer, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2018 Abstract Successful Marketing Strategies Employed by Traditional AM/FM Radio Stations by Shaquilla N. Smith MBA, University of Phoenix, 2011 BA, University of West Florida, 2001 Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Business Administration Walden University December 2018 Abstract An increase in Internet radio adverting spending is negatively affecting the revenue of traditional radio stations. Some general managers and sales directors at traditional radio stations lack marketing strategies to compete effectively with Internet radio. -

Music in Advertising: an Analytic Paradigm

Music in Advertising: An Analytic Paradigm DAVID HURON DVERTISING is the means by which one party attempts to A convince or entice another into purchasing a particular product or service. It differs from the sort of one-on-one sales pitch an individual might encounter at the point of sale in that it addresses a larger, more general audience. Advertising therefore differs substantially from persuasive conversation insofar as it relies entirely on mass media and consequently on widespread social meanings rather than personal or idiosyncratic motivations for purchasing. Historically, advertising was first introduced in print media. Early newspapers were short broadsheets entirely filled with news text; newspaper revenues came only through reader subscription. The advent of newspaper advertising created a dual revenue system in which income was gathered from both subscribers and advertisers. The advertising message was "piggybacked" on the news stories. Newspapers consequently sold two commodities: to the subscriber, they sold news stories; to the advertiser, they sold access to a market of a certain sort. With the advent of photography and photolithography, the "illustrated news" broadsheets gave birth to the modern magazine. While retaining a partial news orientation, the magazine fostered review, biographical pieces, analytic "features," and photo spreads. More important, technical innovations permitted more sophisticated advertising—employing eye-catching full-page photographs. Approximately two-thirds of newspaper and magazine revenues are now generated from the advertising. A magazine's primary market has thus shifted from readers to advertisers. 557 558 The Musical Quarterly Most publishers openly acknowledge the changed nature of their products—the Toronto Globe and Mail, for example, has noted that The definition of the product of a modern newspaper . -

Unit 9 Advertising on Radio

UNIT 9 ADVERTISING ON RADIO Structure Introduction Objectives Advertising Media 9.2.1 The Print Medium 9.2.2 Television 9.2.3 Outdoor Media 9.2.4 Radio Types of Advertising 9.3.1 Commercial Advertising 9.3.2 Social Advertising Strengths and Limitations of Advertising on Radio Types of Radio Commercials 9.5.1 Spots 9.5.2 Sponsored Programmes Creating Effective Comnlercials 9.6.1 Developing Adveitisiilg Brief 9.6.2 Advertising Techniques Advertising Research 9.7.1 Pre-testing 9.7.2 Post-testing Advertising Code Let Us Sum Up Glossary Check Your Progress: Possible Answers - -- 9.0 INTRODUCTION Adverbsing often dictates what we do- the clothes we wear, scooters we drive, soaps we buy, toothpaste we use, etc. Advertising is inextricably Interwoven into our daily lives as the commercial breaks have become an integral part of the programme fare. No wonder, when a little girl went to buy a soap and the shopkeeper asked which brand she wanted, she replied: "I can hum the commerc~alfor you." Advertising has been defined as 'a paid form of impersonal presentation of ideas, goods, or services by an identified sponsor' by the American Marketing Association. Advertising is an activity that is aimed at creating awareness and thereby arousing interest in a product, a service or an idea to elicit the desired sales responses from the target audience. It gives a competitive edge to the product by presenting it to the prospective buyers in the most absorbing way possible. The marketing environment has undergone rapid changes as a result of the transition of the Indian economy from a controlled t6 a free market economy, from protection to competition, from isolation to globalisation and from obsolescence to innovation. -

Advertising Theory

ADVERTISING THEORY EDITED BY SHELLY RODGERS AND ESTHER THORSON Advertising Theory Advertising Theory provides detailed and current explorations of key theories in the advertising discipline. The volume gives a working knowledge of the primary theoretical approaches of advertising, offering a comprehensive syn- thesis of the vast literature in the area. Editors Shelly Rodgers and Esther Thorson have developed this volume as a forum in which to compare, contrast, and evaluate advertising theories in a comprehensive and structured presenta- tion. Chapters provide concrete examples, case studies, and readings written by leading advertising scholars and educators. Utilizing McGuire’s persuasion matrix as the structural model for each chapter, the text offers a wider lens through which to view the phenomenon of advertising as it operates within various environments. Within each area of advertising theory—and across advertising contexts—both traditional and non- traditional approaches are addressed, including electronic word-of-mouth advertising, user-generated advertising, and social media advertising contexts. As a benchmark for the current state of advertising theory, this text will facilitate a deeper understanding for advertising students, and will be required reading for advertising theory coursework. Shelly Rodgers is Associate Professor of Strategic Communication at the Mis- souri School of Journalism. Her research focuses on advertising, health com- munication, and new technology. She is Past President of the American Academy of Advertising. Esther Thorson is Associate Dean for Graduate Studies and Research and Director of Research for the Donald W. Reynolds Journalism Institute. She has more than 100 publications on advertising, media economics, and health com- munication. She is a Fellow of the American Academy of Advertising. -

40 3. Sales Promotion. Such Shares Are Characterized by the Fact That

3. Sales promotion. Such shares are characterized by the fact that companies deduct a portion of the revenues, income, percentage of sales to social problems [1]. The important element of social marketing is to assess the results. Social marketing programs require tracking of each item in the program in order to identify gaps and unexpected obstacles, which allow you to adjust the program en route. Comparative evaluation of the costs and the results will help to choose a way forward in the field of social marketing and how to determine the most and least effective way to implement it. Currently, social marketing demonstrates its ability to enhance the effectiveness of the changes in society. So it is a relatively new approach, only a few people get trained to practice social marketing. With the development of social marketing programs in this area will appear more experienced professionals. With the emergence of new scientific discoveries social marketing can play a role in informing and encouraging people to change their behavior in a changing world. References 1. Vagina E. Marketing&Charity // BTL-magazine. – 2007. – № 5. 2. http://uadeti.com 3. http://www.marketing.spb.ru 4. http://www.marketch.ru 5. http://www.adme.ru RADIO ADVERTISEMENT Lipatova A.V., student National Research Tomsk Polytechnic University A radio advertisement is a type of commercial created for the radio broadcasting medium. Typically 30- 60 seconds long, radio advertisements often rely on memorable audio cues, such as jingles or catch phrases, to grab audience attention. With a low production cost and the ability to target specific demographics through station selection, a radio advertisement can be an excellent way to get the word out about a product or company [1]. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 02-575 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States NIKE, INC., et al., Petitioners, v. MARC KASKY, _______________________________ Respondent. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF CALIFORNIA BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE THE ASSOCIATION OF NATIONAL ADVERTISING, INC., THE AMERICAN ADVERTISING FEDERATION, AND THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF ADVERTISING AGENCIES IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS HOWARD J. RUBIN Counsel of Record RONALD R. URBACH JOSEPH J. LEWCZAK MARC J. RACHMAN CORY GREENBERG DAVIS & GILBERT LLP 1740 Broadway New York, NY 10019 (212) 468-4800 Counsel for Amici Curiae 179329 A ((800) 274-3321 • (800) 359-6859 i QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Does the California Supreme Court’s “limited- purpose” test for determining whether speech by a corporation is commercial or noncommercial speech violate the First Amendment? 2. If Nike’s speech is deemed commercial speech, did the California Supreme Court violate the First Amendment by failing to properly apply the Central Hudson test? 3. Are Sections 17204 and 17535 of the California Business and Professions Code unconstitutional as applied by the court below because the statutes are vague and overbroad and allow a private party to sue without showing any harm from the speech in question? ii TABLECited OF Authorities CONTENTS Page Questions Presented . i Table of Contents . ii Table of Cited Authorities . iv Interest of Amici Curiae . 1 Summary of Argument . 1 I. The California Supreme Court’s “Limited- Purpose” Test Violates The First Amendment Because Nike’s Speech Is Fully Protected Noncommercial Speech . 5 A. This Court’s Decisions In Thornhill And Thomas Held That Speech Like Nike’s Is Protected By The First Amendment . -

The Effectiveness of Radio Marketing in Branding – Perceptions of Smes

The effectiveness of radio marketing in branding – perceptions of SMEs Jarkko Pitkänen Master’s thesis October 2019 School of Business Master of Business Administration, Degree Programme in Entrepreneurship and Business Competence Description Author(s) Type of publication Date Pitkänen, Jarkko Master’s thesis October, 2019 Number of pages Language of publication: 71 English Permission for web publication: x Title of publication The effectiveness of radio marketing in branding – perceptions of SMEs Degree programme Master of Business Administration, Degree Programme in Entrepreneurship and Business Competence Supervisor(s) Kujala, Irene Assigned by JAMK Centre for Competitiveness Abstract The radio and media overall have been researched by radio organizations and media agencies, but this research has paid little attention to SMEs and their local effectiveness. For locally operating SMEs, competition with big national and international corporations means focusing on building a strong brand on the desired market. Digital marketing has gained a great deal of publicity, which often includes misconceptions regarding the effectiveness of various media. The objective of the study was to understand the impact of radio advertising on SMEs’ brands and to determine how they perceived brands and branding through radio advertising and whether there was something specific that had worked and not worked. The study was conducted by interviewing seven SMEs that had been using radio advertising annually about their perceptions and experiences of radio advertising on a local market. The answers were compared to the pre-existing theories of customer-based brand equity and studies of media performance. According to the results, the radio was a strong media for SME brand building. -

Advertising Assignment

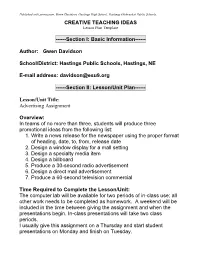

Published with permission, Gwen Davidson, Hastings High School, Hastings (Nebraska) Public Schools. CREATIVE TEACHING IDEAS Lesson Plan Template ------Section I: Basic Information------ Author: Gwen Davidson School/District: Hastings Public Schools, Hastings, NE E-mail address: [email protected] ------Section II: Lesson/Unit Plan------ Lesson/Unit Title: Advertising Assignment Overview: In teams of no more than three, students will produce three promotional ideas from the following list: 1. Write a news release for the newspaper using the proper format of heading, date, to, from, release date 2. Design a window display for a mall setting 3. Design a specialty media item 4. Design a billboard 5. Produce a 30-second radio advertisement 6. Design a direct mail advertisement 7. Produce a 60-second television commercial Time Required to Complete the Lesson/Unit: The computer lab will be available for two periods of in-class use; all other work needs to be completed as homework. A weekend will be included in the time between giving the assignment and when the presentations begin. In-class presentations will take two class periods. I usually give this assignment on a Thursday and start student presentations on Monday and finish on Tuesday. Grade Level: 11/12 Course: Beginning Marketing or Entrepreneurship Targeted NBEA Standards: Students will be able to demonstrate their knowledge of the promotional mix including sales promotion, personal selling, advertising, and publicity. Students will be able to define the differences between promotional media formats and design/produce an example of three different forms of promotion. Students will be able to demonstrate their understanding of the promotion function of marketing. -

Marketing Affects of Noodles by Radio Advertisement on the Consumption of Noodles (Rum Pum) in Nepal

Journal of Research in Business, Economics and Management (JRBEM) ISSN: 2395-2210 SCITECH Volume 8, Issue 4 RESEARCH ORGANISATION April 23, 2017 Journal of Research in Business, Economics and Management www.scitecresearch.com Marketing Affects of Noodles by Radio Advertisement on the Consumption of Noodles (Rum Pum) In Nepal Shailendra Siwakoti Faculty of Management,T.U.M.M.A.M.Campus,Biratnagar,Nepal. Abstract This paper is projected brunt of advertising burning up of noodles in Nepal. Advertising is a part of everyday life for everyone, hence it is difficult to escape them even if we never go through the television program or listen to the FM[Frequency Modulation] radios or read newspaper or magazines. We would still by bombared with the advertisements through billboards at the highways shopping complex, Bus Park, crossway posters in the shops and offices and pamphlets in the wall. More than that advertising is in the form of the leaflets too. The sponsor is notorious by his company’s name or brand name or both. By an aid, the sponsor is not identified and it is not paid for its use of media in which it has appeared then the significance point is considered to be publicity by qualitative and quantatively study too. Keywords: Advertisement; Qualitative; Quantative; Crossway; Sponsor. Introduction Marketing has been developing together with every other development in human civilization. It covers the very wide area now has not been developed at once. If we go several centuries back to the history of human civilization, we find the contemporary marketing as used today. -

Consumer Perception of Modern and Traditional Forms of Advertising

sustainability Article Consumer Perception of Modern and Traditional Forms of Advertising Marcela Korenkova , Milan Maros * , Michal Levicky and Milan Fila Faculty of Natural Sciences, Institute of Economics and Management, Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra, Tr. A. Hlinku 1, 949 01 Nitra, Slovakia; [email protected] (M.K.); [email protected] (M.L.); mfi[email protected] (M.F.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 25 September 2020; Accepted: 26 November 2020; Published: 30 November 2020 Abstract: If a company wants to succeed in a tough competitive environment, it must consider all the options to be more visible. One of these possibilities is advertising, which exists in a considerable variety of forms. Therefore, our goal was to conduct a survey on the attitude of customers in Slovakia to several modern and traditional forms of advertising, which are used by companies for their visibility. Data were obtained from the questionnaires filled in by 244 respondents. We were interested in opinions on advertising oversaturation, the influence of advertising, annoyance by advertising, and credibility of advertising. In each of four topics, we investigated opinions on 21 different types of advertising, using non-parametric tests to determine the significance of differences, which means we used inductive statistics. According to respondents, the advertising on social networks has a higher influence than most other types of advertising. At the same time, it is not one of the most trusted forms, nor one of the most bothering forms. The right marketing strategy choice concerning time, money, form, and efficiency is a key factor to companies. Therefore, it is important for companies to use the right form or combination of forms of advertising to make themselves known depending on the type of product and its target group.