Defending SEC and DOJ FCPA Investigations and Conducting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ICAC Annual Report 2006-2007 Independent Commission Against Corruption

Annual report Annual 2006-2007 ICAC Annual report 2006-2007 Independent Commission Against Corruption Against Commission Independent Independent Commission Against Corruption ADDRESS Level 21, Piccadilly Centre, 133 Castlereagh Street, Sydney NSW 2000 POSTAL GPo Box 500, Sydney NSW 2001 EMAIL [email protected] TELEPHONE (02) 8281 5999 or 1800 463 909 (toll-free for callers outside metropolitan Sydney) TTY (02) 8281 5773 (for hearing-impaired callers only) FACSIMILE (02) 9264 5364 WEBSITE www.icac.nsw.gov.au BUSINESS HOURS 9.00 am – 5.00 pm Monday to Friday This publication is available in other formats for the vision-impaired upon request. Please advise of format needed, for example large print or as an ASCII file. ISSN 1033-9973 © October 2007 – Copyright in this work is held by the Independent Commission Against Corruption. Division 3 of the Commonwealth Copyright Act 1968 recognises that limited further use of this material can occur for the purposes of ‘fair dealing’, for example for study, research or criticism etc. However, if you wish to make use of this material other than as permitted by the Copyright Act 1968, please write to the ICAC at GPO Box 500, Sydney NSW 2001. This report was produced in print and electronic formats for a total cost of $29,654. 800 copies of the report were printed and the report is also available on the ICAC website www.icac.nsw.gov.au. Independent Commission Against Corruption ADDRESS Level 21, Piccadilly Centre, 133 Castlereagh Street, Sydney NSW 2000 POSTAL GPo Box 500, Sydney NSW 2001 EMAIL [email protected] -

Book and Is Not Responsible for the Web: Content of the External Sources, Including External Websites Referenced in This Publication

2020 12th International Conference on Cyber Conflict 20/20 Vision: The Next Decade T. Jančárková, L. Lindström, M. Signoretti, I. Tolga, G. Visky (Eds.) 2020 12TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CYBER CONFLicT 20/20 VISION: THE NEXT DECADE Copyright © 2020 by NATO CCDCOE Publications. All rights reserved. IEEE Catalog Number: CFP2026N-PRT ISBN (print): 978-9949-9904-6-7 ISBN (pdf): 978-9949-9904-7-4 COPYRIGHT AND REPRINT PERMissiONS No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence ([email protected]). This restriction does not apply to making digital or hard copies of this publication for internal use within NATO, or for personal or educational use when for non-profit or non-commercial purposes, providing that copies bear this notice and a full citation on the first page as follows: [Article author(s)], [full article title] 2020 12th International Conference on Cyber Conflict 20/20 Vision: The Next Decade T. Jančárková, L. Lindström, M. Signoretti, I. Tolga, G. Visky (Eds.) 2020 © NATO CCDCOE Publications NATO CCDCOE Publications LEGAL NOTICE: This publication contains the opinions of the respective authors only. They do not Filtri tee 12, 10132 Tallinn, Estonia necessarily reflect the policy or the opinion of NATO Phone: +372 717 6800 CCDCOE, NATO, or any agency or any government. NATO CCDCOE may not be held responsible for Fax: +372 717 6308 any loss or harm arising from the use of information E-mail: [email protected] contained in this book and is not responsible for the Web: www.ccdcoe.org content of the external sources, including external websites referenced in this publication. -

Development Centre Studies : the World Economy

Development Centre Studies «Development Centre Studies The World Economy A MILLENNIAL PERSPECTIVE The World Angus Maddison provides a comprehensive view of the growth and levels of world population since the year 1000. In this period, world population rose 22-fold, per capita GDP 13-fold and world GDP nearly 300-fold. The biggest gains occurred in the rich countries of Economy today (Western Europe, North America, Australasia and Japan). The gap between the world leader – the United States – and the poorest region – Africa – is now 20:1. In the year 1000, the rich countries of today were poorer than Asia and Africa. A MILLENNIAL PERSPECTIVE The book has several objectives. The first is a pioneering effort to quantify the economic performance of nations over the very long term. The second is to identify the forces which explain the success of the rich countries, and explore the obstacles which hindered advance in regions which lagged behind. The third is to scrutinise the interaction between the rich and the rest to assess the degree to which this relationship was exploitative. The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective is a “must” for all scholars of economics and economic history, while the casual reader will find much of fascinating interest. It is also a monumental work of reference. The book is a sequel to the author’s 1995 Monitoring the Economy: A Millennial Perspective The World World Economy: 1820-1992 and his 1998 Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run, both published by the OECD Development Centre. All OECD books and periodicals are now available on line www.SourceOECD.org www.oecd.org ANGUS MADDISON This work is published under the auspices of the OECD Development Centre. -

ICAC Annual Report 2006-2007 Independent Commission Against Corruption

Annual report Annual 2006-2007 ICAC Annual report 2006-2007 Independent Commission Against Corruption Against Commission Independent Independent Commission Against Corruption ADDRESS Level 21, Piccadilly Centre, 133 Castlereagh Street, Sydney NSW 2000 POSTAL GPo Box 500, Sydney NSW 2001 EMAIL [email protected] TELEPHONE (02) 8281 5999 or 1800 463 909 (toll-free for callers outside metropolitan Sydney) TTY (02) 8281 5773 (for hearing-impaired callers only) FACSIMILE (02) 9264 5364 WEBSITE www.icac.nsw.gov.au BUSINESS HOURS 9.00 am – 5.00 pm Monday to Friday This publication is available in other formats for the vision-impaired upon request. Please advise of format needed, for example large print or as an ASCII file. ISSN 1033-9973 © October 2007 – Copyright in this work is held by the Independent Commission Against Corruption. Division 3 of the Commonwealth Copyright Act 1968 recognises that limited further use of this material can occur for the purposes of ‘fair dealing’, for example for study, research or criticism etc. However, if you wish to make use of this material other than as permitted by the Copyright Act 1968, please write to the ICAC at GPO Box 500, Sydney NSW 2001. This report was produced in print and electronic formats for a total cost of $29,654. 800 copies of the report were printed and the report is also available on the ICAC website www.icac.nsw.gov.au. Independent Commission Against Corruption ADDRESS Level 21, Piccadilly Centre, 133 Castlereagh Street, Sydney NSW 2000 POSTAL GPo Box 500, Sydney NSW 2001 EMAIL [email protected] -

2019 Social Responsibility Report Table of Contents

(HONG KONG STOCK CODE: 1913) 2019 SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER TO STAKEHOLDERS 3 4. HUMAN CAPITAL 42 4.1 Workforce 43 1. THE PRADA GROUP 4 4.2 Diversity and equal opportunity 45 1.1 History 5 4.3 Diversity and Inclusion Advisory Council 46 1.2 Value chain 8 4.4 Prada Academy and skills development 46 1.3 Creativity and excellence 11 4.5 Talent attraction and retention 49 1.4 Customer centricity 12 4.6 Worker safety 51 1.5 2019 Highlights 13 4.7 Group’s qualified vendor list procedure 52 2. RESPONSIBLE MANAGEMENT 16 5. CULTURAL INITIATIVES 54 2.1 Governance model and institutional 5.1 Shaping a Sustainable Future Society 55 compliance 17 5.2 Fondazione Prada 56 2.2 The Group’s ethical values 19 5.3 Prada Mode and “Conversations” 2.3 Risk management 22 projects 60 2.4 Trademark protection 24 2.5 Collaborations and cooperations 28 6. NOTES ON THE METHODOLOGY 62 2.6 Ties with the community 31 6.1 The material aspects identification 62 6.2 The reporting process 66 3. ENVIRONMENT 33 3.1 Preservation of the territory 34 7. GRI CONTENT INDEX FOR 3.2 Environmental impact mitigation 35 "IN ACCORDANCE" CORE OPTION 68 3.3 Responsible sourcing and use of resources 38 LETTER TO STAKEHOLDERS Nowadays sustainability topics, particularly environmental and social ones, are shared at every level, ranging from individuals to institutions. Even more significant, they represent sound values that transcend all cultures. Corporations, a basic component of civil society, as well as families and public institutions must share full responsibility for the profound change underway and must contribute to an improvement in the living conditions of the future generations. -

Annual Report 2003-2004

03-04 Annual report 2003–2004 03-04 Annual report Annual What is the ICAC and what do we do? 2003–2004 The Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) is a New South Wales public sector organisation, created by the Independent Commission Against Corruption Act 1988 (ICAC Act). Although a public authority, it is independent of the government of the day, and is accountable to the people of NSW through the NSW Parliament. In order to build and sustain integrity in the NSW public sector, the ICAC: assesses and profiles complaints made by individuals and reports made by Chief Executive Officers of public authorities investigates corrupt conduct not just to make findings about individuals, but to examine the circumstances that allowed the corruption to occur. Recommendations are made and guidance is given to prevent these circumstances recurring builds corruption resistance by providing advice, information and training to remedy potential or real problems, by tailoring solutions to address major risks or assist targeted sectors and by working with the public sector to build their capacity to identify and deal with corruption risks. Independent Commission Against Corruption To ensure the proper and effective performance of these functions, the ICAC: is accountable to the people of NSW, through the Parliament, and meets statutory and other reporting requirements manages, supports and develops its staff in support of these activities. The Annual Report is structured around the five key functions outlined above. Independent Commission Against -

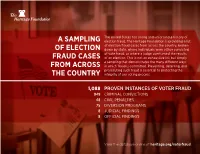

A Sampling of Election Fraud Cases

The United States has a long and unfortunate history of A SAMPLING election fraud. The Heritage Foundation is providing a list of election fraud cases from across the country, broken OF ELECTION down by state, where individuals were either convicted of vote fraud, or where a judge overturned the results FRAUD CASES of an election. This is not an exhaustive list but simply a sampling that demonstrates the many different ways FROM ACROSS in which fraud is committed. Preventing, deterring, and prosecuting such fraud is essential to protecting the THE COUNTRY integrity of our voting process. 1,088 PROVEN INSTANCES OF VOTER FRAUD 949 CRIMINAL CONVICTIONS 48 CIVIL PENALTIES 75 DIVERSION PROGRAMS 8 JUDICIAL FINDINGS 8 OFFICIAL FINDINGS View the database online at heritage.org/voterfraud. KEY Types of Cases Types of Voter Fraud CRIMINAL CONVICTION: Any case that results in a defendant IMPERSONATION FRAUD AT THE POLLS: Voting in the name entering a plea of guilty or no contest, or being found guilty in court of other legitimate voters and voters who have died, moved away, or of election-related offenses. lost their right to vote because they are felons, but remain registered. CIVIL PENALTY: Any civil case resulting in fines or other penalties FALSE REGISTRATIONS: Voting under fraudulent voter imposed for a violation of election laws. registrations that either use a phony name and a real or fake address or claim residence in a particular jurisdiction where the registered DIVERSION PROGRAM: Any criminal case in which a judge voter does not actually live and is not entitled to vote. -

Annual Report 2004–2005 This Publication Is Available in Other Formats for the Vision-Impaired Upon Request

Annual report 2004–2005 This publication is available in other formats for the vision-impaired upon request. Please advise of format needed, for example large print or as an ASCII file. ISSN 1033-9973 © October 2005 – Copyright in this work is held by the Independent Commission Against Corruption. Division 3 of the Commonwealth Copyright Act 1968 recognises that limited further use of this material can occur for the purposes of ‘fair dealing’, for example for study, research or criticism etc. However, if you wish to make use of this material other than as permitted by the Copyright Act 1968, please write to the ICAC at GPO Box 500, Sydney NSW 2001. This report was produced in print and electronic formats for a total cost of $25,080. 800 copies of the report were printed and the report is also available on the ICAC website www.icac.nsw.gov.au Independent Commission Against Corruption ADDRESS Level 21, Piccadilly Centre, 133 Castlereagh Street, Sydney NSW 2000 POSTAL GPO Box 500 Sydney NSW 2001 EMAIL [email protected] TELEPHONE (02) 8281 5999 or 1800 463 909 (toll free) TTY (02) 8281 5773 FACSIMILE (02) 9264 5364 WEBSITE www.icac.nsw.gov.au BUSINESS HOURS 9am–5pm Monday to Friday ICAC Annual Report 2004–2005 1 The Hon. Dr Meredith Burgmann MLC The Hon. John Aquilina MP President Speaker Legislative Council Legislative Assembly Parliament House Parliament House Sydney NSW 2000 Sydney NSW 2000 31 October 2005 Madam President Mr Speaker The ICAC’s Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2005 has been published in accordance with the Independent Commission Against Corruption Act 1988, and the Annual Reports (Departments) Act 1985. -

Countering Corruption Through U.S. Foreign Assistance

Countering Corruption Through U.S. Foreign Assistance May 27, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46373 SUMMARY R46373 Countering Corruption Through U.S. May 27, 2020 Foreign Assistance Michael A. Weber Foreign corruption has been a growing U.S. foreign policy concern in recent decades and is Analyst in Foreign Affairs viewed as intersecting with a variety of issues that are of congressional interest, including promoting democracy and human rights, deterring transnational crime and terrorism, and Katarina C. O'Regan advancing economic development. This report focuses on one tool that the United States uses to Analyst in Foreign Policy combat corruption: foreign assistance. As a component of U.S. efforts to foster transparent and accountable governance overseas, the United States seeks to utilize foreign assistance to address corruption both within target countries and transnationally. Congress has expressed particular Nick M. Brown interest in these issues as the United States reflects on the arguable role of corruption in Analyst in Foreign undermining U.S. efforts to rebuild Afghanistan, and as corruption continues to afflict major U.S. Assistance and Foreign aid recipients, such as Ukraine and Haiti. Several bills proposed in the 116th Congress articulate Policy the interests of Members in corruption issues related to foreign assistance, such as preventing the corrupt misappropriation of aid, ensuring greater coordination of good governance and anti- corruption assistance, combating corruption in particular countries, and broader anti-corruption foreign policy issues. The executive branch implements several approaches to address corruption through foreign assistance. Programs dedicated to promoting democracy and good governance, such as those overseen by the U.S. -

The Threat of Russian Organized Crime

01-Covers 7/30/01 3:38 PM Page 1 U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice The Threat of Russian Organized Crime James O. Finckenauer and Yuri A.Voronin Issues in International Crime 01-Covers 7/30/01 3:38 PM Page 2 U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs 810 Seventh Street N.W. Washington, DC 20531 John Ashcroft Attorney General Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice World Wide Web Site World Wide Web Site http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/nij 02-Inside 7/30/01 3:38 PM Page i The Threat of Russian Organized Crime James O. Finckenauer and Yuri A.Voronin June 2001 NCJ 187085 Issues in International Crime 02-Inside 7/30/01 3:38 PM Page ii National Institute of Justice James O. Finckenauer is director of the International Center of the National Institute of Justice, which is the research arm of the U.S. Department of Justice. He is on leave from the Rutgers University School of Criminal Justice, where he is a professor of criminal justice. Professor Finckenauer is the author or coauthor of six books as well as numerous articles and reports. His latest books are Russian Mafia in America (Northeastern University Press, 1998) and Scared Straight and the Panacea Phenomenon Revisited (Waveland Press, 1999). Yuri A. Voronin served as a visiting international fellow with the National Institute of Justice from March 1, 1999, to March 1, 2000. At the time of his fellowship, he was both a full professor at the Urals State Law Academy and director of the Organized Crime Study Center at the Urals State Law Academy. -

Corruption Matters Issue 36

Corruption Matters November 2010 || Number 36 || ISSN 1326 432X Contents Corruption Matters is also available to download from the ICAC Who cares about value for website www.icac.nsw.gov.au money when it’s not your 2 money? Commissioner’s editorial by Dr Robert Waldersee, ICAC Executive Director, 3 Corruption Prevention, Education and Research Who cares about value for money when it’s not your money? Cont. from p.1 Division In-house procurement training on offer In classic markets where procurement negotiations take place on almost identical goods and services, individuals are motivated 4 by self interest; that is, the seller won’t sell for less than they Lessons from recent ICAC investigations have to, and the buyer won’t buy for more than they have to. A public sector code of conduct: an important The result is a system that regulates itself. But in organisational symbol procurement of somewhat unique goods and services, this individual motivation becomes less of a natural regulator of the 5 procurement transaction. Corruption prevention tools that address diversity In response, the private sector employs a variety of mechanisms to align the goals of the individual with those of the organisation (the basis 6 of Prinicpal-Agent models), such as offering employees stock options, Recruitment: making better employment decisions bonuses, promotions, and a share of the profits. This alignment of New guidelines for referred investigations individual motivation tends to be absent in much of the public sector. As US economist Milton Freidman once said, government is about spending someone else’s money on someone else.