Qigong (Also Spelled Qi Gong and Chi-Kung)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Falun Gong in China: a Sociological Perspective*

The Falun Gong in China: A Sociological Perspective* Cheris Shun-ching Chan ABSTRACT This article offers a sociological perspective on the rise of and crackdown on the falun gong in relation to the social, cultural and political context of China. I specify from a sociological perspective that the falun gong is categorically not a sect but a cult-like new religious movement. Its popularity, I suggest, is related to the unresolved secular problems, normative breakdown and ideological vacuum in China in the 1980s and 1990s. Before the crackdown, the falun gong represented a successful new religious movement, from a Euro-American perspective. However, most of its strengths as a movement have become adversarial to its survival in the specific historical and political condition of China. The phenomenal growth and overseas expansion of the falun gong (FLG; also known as the falun dafa) surprised the Chinese leadership. On the other hand, the heavy-handed crackdown launched by the Chinese government on this group startled world-wide observers. This article attempts to understand the rise and fall of the FLG from a sociological perspective. Applying theoretical insights from the sociology of new religious movements (NRM), it explores how the contemporary socio- cultural context of China contributed to the popularity of religious and quasi-religious qigong movements like the FLG and why the Chinese government launched a severe crackdown on this particular group. In the late 1980s there were already many religious and quasi-religious qigong groups in mainland China.1 A sociological analysis of the popular- ity of the FLG will contribute to an understanding of the “qigong fever” phenomenon in China. -

Falun Gong in the United States: an Ethnographic Study Noah Porter University of South Florida

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 7-18-2003 Falun Gong in the United States: An Ethnographic Study Noah Porter University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Porter, Noah, "Falun Gong in the United States: An Ethnographic Study" (2003). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/1451 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FALUN GONG IN THE UNITED STATES: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY by NOAH PORTER A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: S. Elizabeth Bird, Ph.D. Michael Angrosino, Ph.D. Kevin Yelvington, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 18, 2003 Keywords: falungong, human rights, media, religion, China © Copyright 2003, Noah Porter TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES...................................................................................................................................iii LIST OF FIGURES................................................................................................................................. iv ABSTRACT........................................................................................................................................... -

Jiang Zemin and the Falun Gong Crackdown: a Bibliography Michael J

International Journal of Legal Information the Official Journal of the International Association of Law Libraries Volume 34 Article 9 Issue 3 Winter 2006 1-1-2006 A King Who Devours His People: Jiang Zemin and the Falun Gong Crackdown: A Bibliography Michael J. Greenlee University of Idaho College of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/ijli The International Journal of Legal Information is produced by The nI ternational Association of Law Libraries. Recommended Citation Greenlee, Michael J. (2006) "A King Who Devours His People: Jiang Zemin and the Falun Gong Crackdown: A Bibliography," International Journal of Legal Information: Vol. 34: Iss. 3, Article 9. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/ijli/vol34/iss3/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Legal Information by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A King Who Devours His People+: Jiang Zemin and the Falun Gong Crackdown: A Bibliography MICHAEL J. GREENLEE∗ Introduction In July 1999, the government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) began an official crackdown against the qigong cultivation1 group known as Falun Gong.2 Intended to quickly contain and eliminate what the PRC considers an evil or heretical cult (xiejiao), the suppression has instead created the longest sustained and, since the Tiananmen Square protests of June 1989, most widely known human rights protest conducted in the PRC. -

China Perspectives, 2009/4 | 2009 David A

China Perspectives 2009/4 | 2009 Religious Reconfigurations in the People’s Republic of China David A. Palmer, Qigong Fever: Body, Science, and Utopia in China / La Fièvre du Quigong: guérison, religion, et politique en Chine, 1949-1999 New York, Columbia University Press, 2007, 356 pp. / Paris, Editions de l'EHESS, 2005, 512 pp. Georges Favraud Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/4949 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.4949 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 31 December 2009 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Georges Favraud, « David A. Palmer, Qigong Fever: Body, Science, and Utopia in China / La Fièvre du Quigong: guérison, religion, et politique en Chine, 1949-1999 », China Perspectives [Online], 2009/4 | 2009, Online since 13 January 2010, connection on 24 September 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/4949 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives. 4949 This text was automatically generated on 24 September 2020. © All rights reserved David A. Palmer, Qigong Fever: Body, Science, and Utopia in China / La Fièvre... 1 David A. Palmer, Qigong Fever: Body, Science, and Utopia in China / La Fièvre du Quigong: guérison, religion, et politique en Chine, 1949-1999 New York, Columbia University Press, 2007, 356 pp. / Paris, Editions de l'EHESS, 2005, 512 pp. Georges Favraud 1 Qigong Fever is the English version of David Palmer's thesis (supervised by Kristofer Schipper and submitted for oral examination in 2002), which was previously published in French in 2005 by the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales. This work relates how Chinese breathing control techniques, or qigong, were initially "launched from within socialist state institutions in the 1950s, before becoming the carriers of urban China's most popular form of religious expression in the 1980s, and later a powerful and enduring challenge to the legitimacy of China's political leadership in the late 1990s" (p. -

Ecole De Qi Gong Chuan Ecole De Qi Gong Chuan

ECOLE DE QI GONG CHUANCHUAN----SHUSHU èreèreère ème bilan et planification ‘cursus 1 et 2 année Programme global réalisé > 1 ère année. Qi Gong 63 heures Joaquim Fernandez PierrePierre----AlainAlain Buck Qi Gong Chuan-Shu - concept méthodologique en cinq phases Qi Gong structure de base – Qi Gong thérapeutique 1). Méditation Taoïste bases fondamentales et explications générales 2). Auto-massages (facial et tout le corps) 3). 15 mouvements conventionnels ‘traditionnel’ 4). les huit mouvements de la soie ’Ba Duan Jin’ Méditation de l’Orbite microcosmique – Qi Gong spirituel (forme ‘Shaolin’ - Henan) la petite circulation céleste 5). Le casque d’énergie (mouvement d’interphases) méthodologie et explications globales du Qi Gong Qi Gong d’assouplissement – Qi Gong thérapeutique mouvements avec respiration et synchronisation du suivi mental Qi Gong des animaux – Qi Gong populaire 21 mouvements traditionnels (forme ‘Shaolin’ - Henan ) ce Tao est adaptable en Qi Gong wai jia (externe) Qi Gong du ballon d’énergie – Tao Badeshuan Itchuan Qi Gong thérapeutique et curatif Qi Gong Sun Cun Yé – Qi Gong Thérapeutique 8 mouvements doubles (forme de Tian Jin) Qi Gong des os ‘Nei Gong de la moelle des os’ – thérapeutique préparatoire au Qi Gong martial, des organes et curatif interne Méditation Chantée ––– Qi Gong Spirituel procédé par la tradition du Qi Gong bouddhiste Yann Delmonico Sidaï Qi Gong – Qi Gong Martial Qi Gong Zhang Guang De – Qi Gong thérapeutique pour nour- (forme ‘Shaolin’ – Henan) rir le Sang et faire circuler le Qi ; de Maître Zhang Guang De travail de renforcement corporel s’accordant au climat Qi Gong du Soleil –Qi Gong Spirituel et thérapeutique Tao de l’Aigle – Qi Gong Dur ce tao peut-être employé de manière chamanique (forme de Chongquing - Sichuan) travail du renforcement corporel s’accordant à la casse Tai Ji Quan 15 heures Yann Delmonico Tai Ji Quan – style Yang. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: the ANTI-CONFUCIAN CAMPAIGN

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE ANTI-CONFUCIAN CAMPAIGN DURING THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION, AUGUST 1966-JANUARY 1967 Zehao Zhou, Doctor of Philosophy, 2011 Directed By: Professor James Gao, Department of History This dissertation examines the attacks on the Three Kong Sites (Confucius Temple, Confucius Mansion, Confucius Cemetery) in Confucius’s birthplace Qufu, Shandong Province at the start of the Cultural Revolution. During the height of the campaign against the Four Olds in August 1966, Qufu’s local Red Guards attempted to raid the Three Kong Sites but failed. In November 1966, Beijing Red Guards came to Qufu and succeeded in attacking the Three Kong Sites and leveling Confucius’s tomb. In January 1967, Qufu peasants thoroughly plundered the Confucius Cemetery for buried treasures. This case study takes into consideration all related participants and circumstances and explores the complicated events that interwove dictatorship with anarchy, physical violence with ideological abuse, party conspiracy with mass mobilization, cultural destruction with revolutionary indo ctrination, ideological vandalism with acquisitive vandalism, and state violence with popular violence. This study argues that the violence against the Three Kong Sites was not a typical episode of the campaign against the Four Olds with outside Red Guards as the principal actors but a complex process involving multiple players, intraparty strife, Red Guard factionalism, bureaucratic plight, peasant opportunism, social ecology, and ever- evolving state-society relations. This study also maintains that Qufu locals’ initial protection of the Three Kong Sites and resistance to the Red Guards were driven more by their bureaucratic obligations and self-interest rather than by their pride in their cultural heritage. -

Glosario De Artes Internas Glosario De Artes Internas

GLOSARIO DE ARTES INTERNAS www.taichichuan.com.es GLOSARIO DE ARTES INTERNAS Este glosario de artes internas chinas se empezó a elaborar en 2001 para chenretiro.com y a partir de 2004 lo seguimos editando y ampliando la redacción y los colaboradores de TAI-CHI CHUAN con los términos que van apareciendo en los artículos publicados. Esta versión incluye los términos aparecidos hasta el nº 19. Los términos chinos aparecen en primer lugar en negrita en transcripción pinyin (Taijiquan, Qigong), y a continuación en Wade-Giles (T'ai chi chüan, Ch'i kung) y / o en transcripción "castellanizada" (Tai chi chuan, Chi kung). Cuando en una entrada aparecen dos transcripciones en chino ( ), la primera es en caracteres tradicionales y la segunda en caracteres simplificados. A Almohada de jade (Yu Zhen) - Punto situado en el cruce del borde occipital con la línea central de la cabeza. Es uno de los tres puntos de la espalda donde el Qi tiende a bloquearse, y el más difícil de abrir. Por eso se conoce también por el nombre de "La puerta de hierro". An - Empujar. Una de las Ocho fuerzas. Se usa la palma de una o ambas manos para empujar al oponente con la intención de que la fuerza penetre en su cuerpo más allá del punto de contacto. Se relaciona con el trigrama Dui (lago/metal), beneficia los pulmones. An jin (An Chin) - Energía oculta. B Ba duan jin (Pa tuan chin) - Ocho piezas de un brocado de seda. Esta conocida forma de Qigong se compone de ocho ejercicios que trabajan sobre estiramientos para fortalecer músculos, tendones y todo el sistema de órganos internos y meridianos. -

Qigong and the Birth of Falun Gong

Modernity and Millenialism in China: Qigong and the Birth of Falun Gong David A. Palmer1 PRE-PUBLICATION VERSION. Article published in Asian Anthropology 2[2003]: 79-110. In the 1980’s and 90’s, China experienced the booming popularity of traditional breathing, gymnastic and meditation techniques, described by media chroniclers as “qigong fever”. At its height, the qigong movement attracted over one hundred million practitioners, making it the most widespread form of popular religiosity in post-Maoist urban China. During this period, breathing and meditation techniques were disseminated to a degree perhaps never before seen in Chinese history. Initially sponsored by Chinese state health institutions in the early days of the Peoples’ Republic to extract useful body techniques from their traditional religious setting, qigong became a conduit for the transmission, modernization and legitimization of religious concepts and practices within the Communist regime. In this article, I suggest that this legitimization was made possible by the elaboration of a utopian discourse of qigong which dovetailed with the millenialist strands of the Party’s official ideology. In a sense, the qigong movement was the fruit of a strange union between popular sectarianism and Chinese communist eschatology. The history of qigong is one of the gradual shift of a medicalized and secularized category towards practices and beliefs which marked an increasing return to the Chinese sectarian tradition, culminating in the emergence of Falun Gong. This article will describe the development of the qigong category from the late 1940’s to the end of the 1990’s, tracing the shifting combinations of practices and concepts which came to be associated with qigong in an evolving ideological and political context, and ending with an analysis of Falun Gong’s rupture with qigong groups. -

Table of Contents 1. Introduction

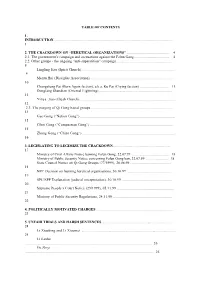

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................ 1 2. THE CRACKDOWN ON “HERETICAL ORGANIZATIONS” .......................................... 4 2.1. The government’s campaign and accusations against the Falun Gong...................................... 4 2.2. Other groups - the ongoing “anti-superstition” campaign........................................................... 8 Lingling Jiao (Spirit Church) ............................................................................................... 9 Mentu Hui (Disciples Association) ..................................................................................... 10 Chongsheng Pai (Born Again faction), a.k.a. Ku Pai (Crying faction) ............................... 11 Dongfang Shandian (Oriental Lightning) ............................................................................ 12 Yiliya Jiao (Elijah Church) ................................................................................................. 12 2.3. The purging of Qi Gong based groups ..................................................................................... 13 Guo Gong (“Nation Gong”) ................................................................................................ 15 Cibei Gong (“Compassion Gong”) ..................................................................................... 15 Zhong Gong (“China Gong”) ............................................................................................. -

Chapter 1 Introduction ------1

Copyright Warning Use of this thesis/dissertation/project is for the purpose of private study or scholarly research only. Users must comply with the Copyright Ordinance. Anyone who consults this thesis/dissertation/project is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no part of it may be reproduced without the author’s prior written consent. CITY UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG 香港城市大學 CHINESE TRADITIONAL SECTS IN MODERN SOCIETY: A CASE STUDY OF YIGUAN DAO 當代社會中的中國傳統教派:一貫道研究 Submitted to Department of Applied Social Studies 應用社會科學系 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 哲學博士學位 by Yunfeng Lu 盧云峰 January 2005 二零零五年一月 i ABSTRACT This study extends the religious economy model to analyzing the operation of Yiguan Dao, a modern successor of Chinese traditional sects. At the individual level, this thesis proposes that the reasons for people’s conversion to Yiguan Dao are a complex of individual rationality, missionary efforts and state suppression. This study also finds that religious experiences, which are deeply personal phenomena, are also influenced by competition in the religious markets. At the group level, this research reveals that Yiguan Dao tried its best to fight against schismatic tendencies, update its theological explanations, and reform its organizational structure to make the sect more theology- centered and more organizationally stabilized, after the sect gained its legal status in 1987. On the macro level, this research analyzes the Chinese religious markets in which Yiguan Dao is located, arguing that Chinese sects bridge, and at the same time are shaped by, the popular religion and the three religions, namely Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism. -

The Red, Black, and Gray Markets of Religion in China

Blackwell Publishing Ltd.Oxford, UK and Malden, USATSQThe Sociological Quarterly0038-02532006 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.200647193122CHINESE MARKETS: ECONOMIC AND RELIGIOUSTriple Religious Markets in ChinaFenggang Yang The Sociological Quarterly ISSN 0038-0253 THE RED, BLACK, AND GRAY MARKETS OF RELIGION IN CHINA Fenggang Yang* Purdue University The economic approach to religion has confined its application to Christendom in spite of the ambition of the core theorists for its universal applicability. Moreover, the supply-side market the- ory focuses on one type of religiosity—religious participation (membership and attendance) in formal religious organizations. In an attempt to analyze the religious situation in contemporary China, a country with religious traditions and regulations drastically different from Europe and the Americas, I propose a triple-market model: a red market (officially permitted religions), a black market (officially banned religions), and a gray market (religions with an ambiguous legal/illegal status). The gray market concept accentuates noninstitutionalized religiosity. The triple-market model is useful to understand the complex religious situation in China, and it may be extendable to other societies as well. Ongoing social change has attracted many sociologists to conduct original research in China (see Bian 2002), but religious change in Chinese society has, with rare exceptions (e.g., Madsen 1998), been neglected. This article seeks to make a twofold contribution: It offers a broad overview of the complex religious situation in contemporary China, and it develops a triple-market model, which may be extendable to other societies, especially to those with heavy regulation of religion. Religion has been reviving in China despite restrictive regulations imposed by the rul- ing Chinese Communist Party (CCP). -

China (Includes Tibet, Hong Kong, Macau) Page 1 of 28

China (Includes Tibet, Hong Kong, Macau) Page 1 of 28 Home » Under Secretary for Democracy and Global Affairs » Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor » Releases » International Religious Freedom » July-December, 2010 International Religious Freedom Report » East Asia and Pacific » China Includes Tibet, Hong Kong, Macau China (Includes Tibet, Hong Kong, Macau) BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR July-December, 2010 International Religious Freedom Report Report September 13, 2011 Reports on Tibet, Hong Kong and Macau are appended at the end of this report. The constitution protects religious freedom for all citizens but, in practice, the government generally enforced other laws and policies that restrict religious freedom. The constitution states that Chinese citizens "enjoy freedom of religious belief" and "normal religious activities," but does not define "normal." It also bans the state, public organizations, and individuals from compelling citizens to believe in, or not believe in, any religion. Only religious groups belonging to one of the five state-sanctioned "patriotic religious associations" (Buddhist, Taoist, Muslim, Catholic, and Protestant) are permitted to register and to hold worship services. Religious groups, such as Protestant groups unaffiliated with a patriotic religious association, or Catholics professing loyalty to the Vatican, are not permitted to register as legal entities. In some parts of the country, authorities charged religious believers unaffiliated with a patriotic religious association with various crimes, including "illegal religious activities" or "disrupting social stability." Proselytizing in public or unregistered places of worship is not permitted. Some religious and spiritual groups are outlawed. Tibetan Buddhists in China are not free to openly venerate the Dalai Lama and encounter severe government interference in religious practice (see Tibet section).