Moray's Lithics – Impressions from Local Museums and Excavations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of the Epidemic in Scotland (9Th April 2021)

th State of the Epidemic in Scotland (9 April 2021) Background This report summarises the current situation on the COVID-19 epidemic in Scotland. It brings together the different sources of evidence and data about the epidemic in Scotland at this point in time, why we are at that place, and what is likely to happen next. This summarises the data up to and including the 8 April 2021 on COVID-19 in Scotland. This updates the previous publication published on 1 April 20211. The information in this document helps the Scottish Government, the health service and the wider public sector respond to the epidemic and put in place what is needed to keep us safe and treat people who have the virus. This edition of the state of the epidemic, summarises current data on COVID-19 at a national level, at a local level and how Scotland currently compares to the rest of the UK. It looks at the vaccination program in Scotland and the effects which are beginning to be seen from this. Information is provided about variants of concern and what impact these may have. Bringing this information together in one place gives the opportunity to better understand the current state of the epidemic in Scotland. Key Points • The reproduction rate R in Scotland is currently estimated as being between 0.8 and 1.0. This is unchanged from the estimate of R as of 31 March. • An average of 331 cases were reported per day in the 7 days to 8 April, which is a 28% decrease in reported cases since the 1 April. -

Local Police Plan 2020 - 23

OFFICIAL Local Police Plan 2020 - 23 Our commitment to the safety and wellbeing of the people and communities of the Lothians and Scottish Borders The Lothians and Scottish Borders OFFICIAL OFFICIAL Planning framework The Chief Constable has responsibility for the policing of Scotland OFFICIAL Page | 1 OFFICIAL Contents Page Foreword 3 The Lothians & Scottish Borders Divisional Context 4 How we Identified the Police Plan Priorities 6 Policing on a Page: The Lothians & Scottish Borders 8 Priority: Protecting the Most Vulnerable People 9 Priority: Reducing Violence & Anti-Social Behaviour 10 Priority: Reducing Acquisitive Crime 11 Priority: Improving Road Safety 12 Priority: Tackling Serious & Organised Crime 13 Performance and Accountability 14 Equality, Diversity and Ethics 15 Local Contact Details 16 OFFICIAL Page | 2 OFFICIAL In pursuit of this aim, the shared outcomes documented within Local Outcome Improvement Plans (LOIPs), as per the Foreword requirement under the terms of the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015, are reflected in this document and outline As Divisional Commander, I am pleased to present the 2020 - our commitment to a collaborative approach with 2023 Local Police Plan for the Lothians & Scottish Borders Policing communities, partners and stakeholders. Division. Police Scotland and by extension the policing team of the The Police and Fire Reform (Scotland) Act 2012 sets out the Lothians and Scottish Borders is committed to providing the statutory framework for Police Scotland, with the mission of highest possible service to East Lothian, Midlothian, Scottish policing being to improve the safety and well-being of persons, Borders and West Lothian by ensuring local teams, supported by localities and communities in Scotland. -

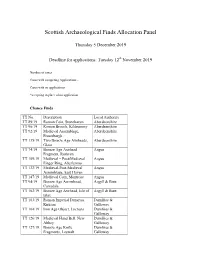

Scottish Archaeological Finds Allocation Panel

Scottish Archaeological Finds Allocation Panel Thursday 5 December 2019 Deadline for applications: Tuesday 12th November 2019 Number of cases – Cases with competing Applications - Cases with no applications – *accepting in place of no application Chance Finds TT No. Description Local Authority TT 89/19 Roman Coin, Stonehaven Aberdeenshire TT 90/19 Roman Brooch, Kildrummy Aberdeenshire TT 92/19 Medieval Assemblage, Aberdeenshire Fraserburgh TT 135/19 Two Bronze Age Axeheads, Aberdeenshire Glass TT 74/19 Bronze Age Axehead Angus Fragment, Ruthven TT 109/19 Medieval – Post-Medieval Angus Finger Ring, Aberlemno TT 132/19 Medieval-Post-Medieval Angus Assemblage, East Haven TT 147/19 Medieval Coin, Montrose Angus TT 94/19 Bronze Age Arrowhead, Argyll & Bute Carradale TT 102/19 Bronze Age Axehead, Isle of Argyll & Bute Islay TT 103/19 Roman Imperial Denarius, Dumfries & Kirkton Galloway TT 104/19 Iron Age Object, Lochans Dumfries & Galloway TT 126/19 Medieval Hand Bell, New Dumfries & Abbey Galloway TT 127/19 Bronze Age Knife Dumfries & Fragments, Leswalt Galloway TT 146/19 Iron Age/Roman Brooch, Falkirk Stenhousemuir TT 79/19 Medieval Mount, Newburgh Fife TT 81/19 Late Bronze Age Socketed Fife Gouge, Aberdour TT 99/19 Early Medieval Coin, Fife Lindores TT 100/19 Medieval Harness Pendant, Fife St Andrews TT 101/19 Late Medieval/Post-Medieval Fife Seal Matrix, St Andrews TT 111/19 Iron Age Button and Loop Fife Fastener, Kingsbarns TT 128/19 Bronze Age Spearhead Fife Fragment, Lindores TT 112/19 Medieval Harness Pendant, Highland Muir of Ord TT -

20Mph Speed Limits Report By

Agenda 16 Item Report ECI/25/2021 No HIGHLAND COUNCIL Committee: Economy and Infrastructure Date: 5 May 2021 Report Title: 20mph Speed Limits Report By: Executive Chief Officer Infrastructure and Environment 1. Purpose/Executive Summary 1.1 This report is brought to the Economy and Infrastructure Committee to provide information and background on the preparation and introduction of 20mph speed limits, and now that the Proposed Restricted Roads (20mph Limit) (Scotland) Bill will not come into force provide a direction going forward for the implementation of 20mph limit schemes in the Highland Council Area. 2. Recommendations 2.1 Members are asked to:- i. Agree that up to £200,000 of the Council’s Cycling, Walking and Safer Routes 2021/22 grant award is allocated to the delivery of a new Council 20mph programme and 10% of this annual budget is used in future years; ii. Approve that an appropriate Assessment Criteria, similar to that detailed in Appendices B and C, for the prioritisation of schemes for a new Council wide 20mph programme is used; iii. Agree that the outstanding 4 schemes from the previous Council programme, namely Invergordon, Tain, Kingussie and Maryburgh, are reassessed using the new criteria as this will include utilisation of recent collision data; iv. Agree that Highland Council continue to lobby through CoSLA for the implementation of the National 20mph Restricted Roads Bill; and v. Agree that Highland Council adopts a policy of supporting 20mph limits in all urban and rural areas in line with current guidance set out in 4.1, with the focus being on benefitting active travel users. -

Volume of Minutes

1 The Highland Council No. 14 2020/2021 Minutes of Meeting of the Highland Council held REMOTELY on Thursday, 10 September 2020 at 10.35am and adjourned/resumed on Friday, 11 September 2020 at 9.00am. 1. Calling of the Roll and Apologies for Absence A’ Gairm a’ Chlàir agus Leisgeulan Present: Mr G Adam Mrs D Mackay Mr B Allan Mr D Mackay Mr R Balfour Mr W MacKay Mrs J Barclay Mr G MacKenzie Mr A Baxter Mrs I MacKenzie Mr B Boyd Mr S Mackie Mr R Bremner Mr A Mackinnon Mr I Brown Ms A MacLean Mr J Bruce Mr C MacLeod Mrs C Caddick Mr D MacLeod Mrs I Campbell Mr D Macpherson Miss J Campbell Mr R MacWilliam Mrs G Campbell-Sinclair Mrs B McAllister Mrs H Carmichael Mr J McGillivray Mr A Christie Mr H Morrison Mr I Cockburn Mr C Munro Mrs M Cockburn Ms L Munro Mrs M Davidson Ms P Munro Mr J Finlayson Mrs M Paterson Mr M Finlayson Mr I Ramon Mr C Fraser Mr M Reiss Mr L Fraser Mr A Rhind Mr R Gale Mr D Rixson Mr J Gordon Mrs F Robertson Mr K Gowans Mrs T Robertson Mr A Graham Ms E Roddick Mr J Gray Mr K Rosie Mrs P Hadley Mr G Ross Mr T Heggie Mr P Saggers Mr A Henderson Mr A Sinclair Mr A Jarvie Ms N Sinclair Ms E Knox Mr C Smith Mr B Lobban Ms M Smith Mr D Louden Mr B Thompson Mrs L MacDonald Mrs C Wilson Mr A MacInnes In Attendance: Chief Executive Executive Chief Officer, Infrastructure & Executive Chief Officer, Communities & Environment Place Executive Chief Officer, Performance & Executive Chief Officer, Education & Governance Learning Executive Chief Officer, Property & Housing Executive Chief Officer, Health & Social Care Executive Chief Officer, Resources & Finance Executive Chief Officer, Economy Mr B Lobban in the Chair 2 Apologies for absence were intimated on behalf of Ms K Currie and Mr N McLean. -

South of Scotland Indicative Regional Spatial Strategy Contents

SOUTH OF SCOTLAND INDICATIVE REGIONAL SPATIAL STRATEGY CONTENTS Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Context ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Ambition ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Strategic Themes and Aims ..........................................................................................................10 Appendix - Strategic Development Projects ..........................................................................16 2 SOUTH OF SCOTLAND | indicative Regional Spatial Strategy Introduction This document presents the indicative Regional Spatial optimum connectivity to, from and throughout our the need for a paradigm-shift towards a greener, net- Strategy (iRSS) for the South of Scotland, a region region. The timescale for the programme set out in zero and wellbeing economy which is why the South which comprises the local authority areas of Dumfries this iRSS is to 2050, with a 10-year review. of Scotland’s role and response to climate change is a and Galloway and the Scottish Borders. In doing so, it cornerstone of this iRSS. seeks to respond to the opportunity presented by the Over the next 30 years, the potential for change is review of the National Planning Framework (NPF) for significant, -

Scottish Borders Dumfries Galloway Migration Report

General Register Office for S C O T L A N D information about Scotland’s people Scottish Borders and Dumfries & Galloway Migration Report Published August 2010 Crown copyright © General Register Office for Scotland (2010) Scottish Borders and Dumfries & Galloway Migration Report General Register Office for Scotland Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Background.................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Research into improving Migration and Population Statistics....................... 3 2. General Register Office for Scotland (GROS) migration data ............................. 5 2.1 Scottish Borders and Dumfries & Galloway recent migration summary - mid-2007 to mid-2008 ............................................................... 5 2.2 Historical net total migration......................................................................... 7 2.3 Migration outside Scotland – net and gross migration flows ........................ 9 2.4 Overseas migration flows........................................................................... 11 2.5 Age-profile of migrants............................................................................... 13 3. Other data that inform on migration................................................................... 14 3.1 NHS registrations from overseas ............................................................... 14 3.2 Country of birth ......................................................................................... -

Borders Railway Business Guide You’Re on the Right Tracks to Develop Your Business

BORDERS RAILWAY BUSINESS GUIDE You’re on the right traCKS TO DEVELOP YOUR BUSINESS You’re on the right traCKS TO DEVELOP YOUR BUSINESS 1 2 BORDERS RAILWAY BUSINESS GUIDE CONTENTS Introduction 3 All On Track 4 Midlothian & Borders: Great Destinations to Visit 5 Opportunities for Business 7 Be Inspired: Case Studies 11 Next Steps: Making the Most of the Opportunities 14 Support and Resources 15 INTRODUCTION Tourism is key to the economic development of Midlothian and the Scottish Borders Tourism is central to to the Midlothian and Scottish Borders’ economies and the opening of the Borders Railway offers an exciting opportunity for tourism businesses to benefit. The investment in the Borders Railway supports the ambitions for growth and will be a catalyst for attracting visitors with the promise of compelling experiences and immersion in Borders’ and Midlothian’s history, heritage, culture and landscape. How can you make the most of the Borders Railway and use it to benefit your business? This guide has been created to help you find out. It is packed with ideas and tips that will give you a competitive edge. It will also help you identify opportunities to drive new custom and enhance the quality of your visitors’ experience. “We are very excited about the Borders Railway. For commuters and tourists alike, the line will provide opportunities to enjoy the beautiful scenery and many attractions on offer between Edinburgh and the Borders.” Gillian Rankin, Marketing & Events Officer National Mining Museum Scotland “The opening of the Borders Railway in 2015 presents exciting opportunities for the Borders region and for Abbotsford. -

1 Nobel Autobiography Angus Deaton, Princeton, February 2016 Scotland

Nobel Autobiography Angus Deaton, Princeton, February 2016 Scotland I was born in Edinburgh, in Scotland, a few days after the end of the Second World War. Both my parents had left school at a very young age, unwillingly in my father’s case. Yet both had deep effects on my education, my father influencing me toward measurement and mathematics, and my mother toward writing and history. The school in the Yorkshire mining village in which my father grew up in the 1920s and 1930s allowed only a few children to go to high school, and my father was not one of them. He spent much of his time as a young man repairing this deprivation, mostly at night school. In his village, teenagers could go to evening classes to learn basic surveying and measurement techniques that were useful in the mine. In Edinburgh, later, he went to technical school in the evening, caught up on high school, and after many years and much difficulty, qualified as a civil engineer. He was determined that I would have the advantages that he had been denied. My mother was the daughter of William Wood, who owned a small woodworking business in the town of Galashiels in the Scottish Borders. Although not well-educated, and less of an advocate for education than my father, she was a great story-teller (though it was sometimes hard to tell the stories from gossip), and a prodigious letter- writer. She was proud of being Scottish (I could make her angry by saying that I was British, and apoplectic by saying that I was English), and she loved the Borders, where her family had been builders and carpenters for many generations. -

Alternative Service Delivery Models in Scottish Local Authorities 2017

Alternative service delivery models in place in Scottish local authorities: summary report May 2017 Authors This report was published by the Improvement Service’s Change Management Team. 2 | Alternative service delivery models in place in Scottish local authorities: Summary report - May 2017 Contents Introduction 5 Context 6 Key findings 9 Current picture 10 Benefits realised 13 Case studies 16 Areas to address 18 Conclusions 19 Alternative service delivery models in place in Scottish local authorities: Summary report - May 2017 | 3 4 | Alternative service delivery models in place in Scottish local authorities: Summary report - May 2017 Introduction In December 2016, the Improvement Service (IS) circulated a survey to all 32 council Chief Executives around the development, implementation and proposed arrangements for Alternative Service Delivery Models (ASDM) across Scotland. The survey was also intended to provide a picture around the scale and scope of ASDMs and how they are being used to assist councils in the design and delivery of services. Furthermore, a core element of the survey was to identify whether councils could quantify the benefits from implementing ASDMs and, if not, what progress was being made towards realising any perceived benefit. Returns were received from the following 15 councils: • Argyll and Bute • Aberdeenshire • Comhairle nan Eilean Siar • East Renfrewshire • Falkirk • Highland • Midlothian • North Ayrshire • Perth and Kinross • Scottish Borders • South Ayrshire • South Lanarkshire • Stirling • West Dunbartonshire • West Lothian. Councils were asked to complete a template to provide the relevant information. In some cases, reports and briefing notes were also supplied. With this in mind, where percentages are identified throughout the report, they are approximations based on the information provided. -

Table 1 Settlements in Alphabetical Order Name Council Area 2004 Population Estimate Revised Aberchirder Aberdeenshire 1,230

Table 1 Settlements in alphabetical order 2004 Population Name Council Area Estimate Revised Aberchirder Aberdeenshire 1,230 Aberdeen, Settlement of Aberdeen City 188,760 r Aberdour Fife 1,690 r Aberfeldy Perth & Kinross 1,950 Aberfoyle Stirling 640 Aberlady East Lothian 1,100 Aberlour Moray 900 Abernethy Perth & Kinross 1,020 Aboyne Aberdeenshire 2,240 Airth Falkirk 1,460 Alford Aberdeenshire 1,950 Allanton North Lanarkshire 1,240 Alloa, Settlement of Clackmannanshire 26,350 Almondbank Perth & Kinross 1,070 Alness Highland 4,960 Alva Clackmannanshire 5,100 Alyth Perth & Kinross 2,370 r Annan Dumfries & Galloway 8,240 Annbank South Ayrshire 850 Anstruther, Settlement of Fife 5,270 Arbroath Angus 22,460 r Ardersier Highland 990 Ardrishaig Argyll & Bute 1,210 Ardrossan, Settlement of North Ayrshire 31,320 Armadale West Lothian 9,890 Auchinleck East Ayrshire 3,450 Auchterarder Perth & Kinross 3,960 Auchtermuchty Fife 2,110 Auldearn Highland 570 Aviemore Highland 2,290 Avoch Highland 1,020 Avonbridge Falkirk 660 Ayr, Settlement of South Ayrshire 60,920 Ayton Scottish Borders 570 Balfron Stirling 1,730 Balintore Highland 1,080 Ballachulish Highland 610 Ballater Aberdeenshire 1,500 Ballingry Fife 5,740 Balmedie Aberdeenshire 2,020 Balmullo Fife 1,370 Banchory Aberdeenshire 6,270 Banff Aberdeenshire 3,920 Settlements in alphabetical order 2004 Population Name Council Area Estimate Revised Bankfoot Perth & Kinross 1,220 Banknock, Settlement of Falkirk 3,220 Bathgate West Lothian 15,650 Beauly Highland 1,140 Beith North Ayrshire 6,250 Bellsbank -

Local Police Plan 2020-23 the Scottish Borders; Police Scotland

OFFICIAL Local Police Plan 2020 - 23 Our commitment to the safety and wellbeing of the people and communities of the Lothians and Scottish Borders The Scottish Borders OFFICIAL OFFICIAL Planning framework The Chief Constable has responsibility for the policing of Scotland OFFICIAL OFFICIAL Contents Page Foreword 3 The Scottish Borders Context 4 How we Identified the Police Plan Priorities 6 Policing on a Page: The Lothians & Scottish Borders 8 Priority: Protecting the Most Vulnerable People 9 Priority: Reducing Violence & Anti-Social Behaviour 10 Priority: Reducing Acquisitive Crime 11 Priority: Improving Road Safety 12 Priority: Tackling Serious & Organised Crime 13 Performance and Accountability 14 Equality, Diversity and Ethics 15 Local Contact Details 16 OFFICIAL Page | 2 OFFICIAL In pursuit of this aim, the shared outcomes documented within the Scottish Borders Community Plan (Local Outcome Foreword Improvement Plan - LOIP), as per the requirement under the terms of the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015, are As Divisional Commander, I am pleased to present the 2020 - reflected in this document and outline our commitment to a 2023 Local Police Plan for the Scottish Borders local authority collaborative approach with communities, partners and area of the Lothians & Scottish Borders Policing Division. stakeholders. The Police and Fire Reform (Scotland) Act 2012 sets out the Police Scotland and by extension the policing team of the statutory framework for Police Scotland, with the mission of Lothians and Scottish Borders is committed to providing the policing being to improve the safety and well-being of persons, highest possible service to the Scottish Borders by ensuring local localities and communities in Scotland.