LUTSF Awardee: Dr Elena Catalano Project Title: Nrityagram Intensive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLIMATRANS Case City Report Bengaluru

CLIMATRANS Case City Presentation Bengaluru Dr. Ashish Verma Assistant Professor Transportation Engineering Dept. of Civil Engg. and CiSTUP Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bangalore, India [email protected] 1 PARTNERS : 2 Key Insights 7th most urbanized State Bangalore is the Capital 5th largest metropolitan city in India in terms of population ‘ Silicon Valley ’ of India District Population: 96, 21,551 District area: 2196 sq. km Density: 6,851 persons/Sq.km City added about 2 million people in just last decade Most urbanized district with 90.94% in Urban areas Figure.1: Bangalore Map Mobility: 4 Long travel times Peak hour travel speed in the city is 17 km/hr Poor road safety, inadequate infrastructure and environmental pollution Over 0.4million new vehicles were registered between 2013 and 2014 Public transport in suburban areas has not developed in pace with urban expansion. Fig.2: Peak hour traffic at Commercial Street Household Growth Households 2377056 5 2500000 2000000 1500000 1278333 859188 1000000 549627 500000 0 1981 1991 2001 2011 Households Area 7 City 1 Town Karnataka State Municipal Municipal Government Notification, Council’s Council January 2007 100 wards of Bangalore 111 villages Mahanagara Around City Palike Bruhat Bangalore Mahanagara Palike 7 Total Metropolitan Urban Surface Area Urban Surface Area (sq.km) 1400 700 1241 741 0 2007 2011 Urban Expansion 8 Figure.4: Map showing urban expansion of Bangalore Economy 9 Initially driven by Public Sector Undertakings and the textile industry. Shifted to high-technology service industries in the last decade. Bangalore Urban District contributes 33.8% to GSDP at Current Prices. -

An Empirical Study of Urban Infrastructure in Bengaluru

International Journal of Applied Research 2016; 2(7): 559-562 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Impact Factor: 5.2 An empirical study of urban infrastructure in IJAR 2016; 2(7): 559-562 www.allresearchjournal.com Bengaluru Received: 01-05-2016 Accepted: 19-06-2016 Mallikarjun Chanmal and Uma TG. Mallikarjun Chanmal Associate Professor and HOD of Commerce, HKES’s Sree Abstract Veerendra Patil Degree There is a strong positive link between national levels of human development and urbanization levels, College, Sadashiva Nagar, while cities spearhead their countries’ economic development, transforming society through Bengaluru-560 080 extraordinary growth in the productivity of labour and promising to liberate the masses from poverty, hunger, disease and premature death. However, the implications of rapid urban growth include Uma TG. increasing unemployment, lack of urban services, overburdening of existing infrastructure and lack of Assistant Professor, access to land, finance and adequate shelter, increasing violent crime and sexually transmitted diseases, Department of Commerce and and environmental degradation. Even as national output is rising, a decline in the quality of life for a Management, Maharani majority of population that offsets the benefit of national economic growth is often witnessed. Women’s Arts, Commerce and Urbanization thus imposes significant burden to sustainable development. Management College, Seshadri Road, Bengaluru-560 001 Keywords: Urban infrastructure, Health, Economic Growth, Waste Collection, Urbanization -

Registered Office Address: Mindtree Ltd, Global Village, RVCE Post, Mysore Road, Bengaluru-560059, Karnataka, India

Registered Office Address: Mindtree Ltd, Global Village, RVCE Post, Mysore Road, Bengaluru-560059, Karnataka, India. CIN: L72200KA1999PLC025564 E-mail: [email protected] Ref: MT/STAT/CS/20-21/02 April 14, 2020 BSE Limited National Stock Exchange of India Limited Phiroze Jeejeebhoy Towers, Exchange Plaza, Bandra Kurla Complex, Dalal Street, Mumbai 400 001 Bandra East, Mumbai 400 051 BSE: fax : 022 2272 3121/2041/ 61 NSE : fax: 022 2659 8237 / 38 Phone: 022-22721233/4 Phone: (022) 2659 8235 / 36 email: [email protected] email : [email protected] Dear Sirs, Sub: Reconciliation of Share Capital Audit Report for the quarter ended March 31, 2020 Kindly find enclosed the Reconciliation of Share Capital Audit Certificate for the quarter ended March 31, 2020 issued by Practicing Company Secretary under Regulation 76 of the SEBI (Depositories and Participants) Regulations, 2018. Please take the above intimation on records. Thanking you, Yours sincerely, for Mindtree Limited Vedavalli S Company Secretary Mindtree Ltd Global Village RVCE Post, Mysore Road Bengaluru – 560059 T +9180 6706 4000 F +9180 6706 4100 W: www.mindtree.com · G.SHANKER PRASAD ACS ACMA PRACTISING COMPANY SECRETARY # 10, AG’s Colony, Anandnagar, Bangalore-560 024, Tel: 42146796 e-mail: [email protected] RECONCILIATION OF SHARE CAPITAL AUDIT REPORT (As per Regulation 76 of SEBI (Depositories & Participants) Regulations, 2018) 1 For the Quarter Ended March 31, 2020 2 ISIN INE018I01017 3 Face Value per Share Rs.10/- 4 Name of the Company MINDTREE LIMITED 5 Registered Office Address Global Village, RVCE Post, Mysore Road, Bengaluru – 560 059. 6 Correspondence Address Global Village, RVCE Post, Mysore Road, Bengaluru – 560 059. -

IPL 2014 Schedule

Page: 1/6 IPL 2014 Schedule Mumbai Indians vs Kolkata Knight Riders 1st IPL Sheikh Zayed Stadium, Abu Dhabi Apr 16, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Delhi Daredevils vs Royal Challengers Bangalore 2nd IPL Sharjah Cricket Association Stadium, Sharjah Apr 17, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Chennai Super Kings vs Kings XI Punjab 3rd IPL Sheikh Zayed Stadium, Abu Dhabi Apr 18, 2014 | 14:30 local | 10:30 GMT Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Rajasthan Royals 4th IPL Sheikh Zayed Stadium, Abu Dhabi Apr 18, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Royal Challengers Bangalore vs Mumbai Indians 5th IPL Dubai International Cricket Stadium, Dubai Apr 19, 2014 | 14:30 local | 10:30 GMT Kolkata Knight Riders vs Delhi Daredevils 6th IPL Dubai International Cricket Stadium, Dubai Apr 19, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Rajasthan Royals vs Kings XI Punjab 7th IPL Sharjah Cricket Association Stadium, Sharjah Apr 20, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Chennai Super Kings vs Delhi Daredevils 8th IPL Sheikh Zayed Stadium, Abu Dhabi Apr 21, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Kings XI Punjab vs Sunrisers Hyderabad 9th IPL Sharjah Cricket Association Stadium, Sharjah Apr 22, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Rajasthan Royals vs Chennai Super Kings 10th IPL Dubai International Cricket Stadium, Dubai Apr 23, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Royal Challengers Bangalore vs Kolkata Knight Riders Page: 2/6 11th IPL Sharjah Cricket Association Stadium, Sharjah Apr 24, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Delhi Daredevils 12th IPL Dubai International Cricket Stadium, Dubai Apr 25, 2014 -

Measures for the Effective Implementation of the Bangalore

MEASURES FOR THE EFFECTIVE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE BANGALORE PRINCIPLES OF JUDICIAL CONDUCT (The Implementation Measures) Adopted by the Judicial Integrity Group at its Meeting held in Lusaka, Zambia 21 and 22 January 2010 CONTENTS Introduction … 3 Part One Responsibilities of the Judiciary 1. Formulation of a Statement of Principles of Judicial Conduct … 6 2. Application and Enforcement of Principles of Judicial Conduct… 6 3. Assignment of Cases … 7 4. Court Administration … 7 5. Access to Justice … 8 6. Transparency in the Exercise of Judicial Office … 8 7. Judicial Training … 10 8. Advisory Opinions … 11 9. Immunity of Judges … 11 Part Two Responsibilities of the State 10. Constitutional Guarantee of Judicial Independence … 12 11. Qualifications for Judicial Office … 13 12. Appointment of Judges … 13 13. Tenure of Judges … 14 14. Remuneration of Judges … 15 15. Discipline of Judges … 15 16. Removal of Judges from Office … 16 17. Budget of the Judiciary … 16 Definitions … 17 2 INTRODUCTION The Bangalore Principles of Judicial Conduct identify six core values of the judiciary – Independence, Impartiality, Integrity, Propriety, Equality, Competence and Diligence. They are intended to establish standards of ethical conduct for judges. They are designed to provide guidance to judges in the performance of their judicial duties and to afford the judiciary a framework for regulating judicial conduct. They are also intended to assist members of the executive and the legislature, and lawyers and the public in general, to better understand the judicial role, and to offer the community a standard by which to measure and evaluate the performance of the judicial sector. The Commentary on the Bangalore Principles is intended to contribute to a better understanding of these Principles. -

Plan Bengaluru 2020

www.•bldebe!IPIUN.In PI an Vffit,})fn\ BENGALURu_i(lj8 {lj Bringing back a Bengaluru of Kempe Gowda's dreams JANUARY 2010 Agenda for Bengaturu With hlnding & support of Infrastructure and Namma Benpluru Foundation Devetopement Task force -.Mmi'I'IIH!enJIIIIUru.ln BENGA~~0 1010 Bringing ba1k a Bengaluru of Kempe Gowda's dreams BE ASTAKEHOLDER OF PLANBENGALURU20201 1. PlanBengaluru2020 marks a significant deliverable for the Abide Task force - following the various reports and recommendations already made. 2. For the first time, there is a comprehensive blueprint and reforms to solve the city's problems and residents' various difficulties. This is a dynamic document that will continuously evolve, since there will be tremendous scope for expansion and improvement, as people read it and contribute to it 3. PlanBengaluru2020 is a powerful enabler for RWAs 1 residents and citizens. It will enable RWAs 1 residents to engage with their elected representatives and administrators on specific solutions and is a real vision for the challenges of the city. 4. The PlanBengaluru2020 suggests governance reforms that will legally ensure involvement of citizens 1 RWAs through Neighbourhood Area Committee and Ward Committee to decide and influence the future/ development of the Neighbourhoods, Wards and City 5. This plan is the basis on which administrators and elected representatives must debate growth, overall and inclusive development and future of Bangalore. 6. The report will be reviewed by an Annual City Report-Card and an Annual State of City Debate/conference where the Plan, its implementation and any new challenges are discussed and reviewed. 7. PlanBengaluru2020 represents the hard work, commitment and suggestions from many volunteers and citizens. -

Bangalore for the Visitor

Bangalore For the Visitor PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 12 Dec 2011 08:58:04 UTC Contents Articles The City 11 BBaannggaalloorree 11 HHiissttoorryoofBB aann ggaalloorree 1188 KKaarrnnaattaakkaa 2233 KKaarrnnaattaakkaGGoovv eerrnnmmeenntt 4466 Geography 5151 LLaakkeesiinBB aanngg aalloorree 5511 HHeebbbbaalllaakkee 6611 SSaannkkeeyttaannkk 6644 MMaaddiiwwaallaLLaakkee 6677 Key Landmarks 6868 BBaannggaalloorreCCaann ttoonnmmeenntt 6688 BBaannggaalloorreFFoorrtt 7700 CCuubbbboonPPaarrkk 7711 LLaalBBaagghh 7777 Transportation 8282 BBaannggaalloorreMM eettrrooppoolliittaanTT rraannssppoorrtCC oorrppoorraattiioonn 8822 BBeennggaalluurruIInn tteerrnnaattiioonnaalAA iirrppoorrtt 8866 Culture 9595 Economy 9696 Notable people 9797 LLiisstoof ppee oopplleffrroo mBBaa nnggaalloorree 9977 Bangalore Brands 101 KKiinnggffiisshheerAAiirrll iinneess 110011 References AArrttiicclleSSoo uurrcceesaann dCC oonnttrriibbuuttoorrss 111155 IImmaaggeSS oouurrcceess,LL iicceennsseesaa nndCC oonnttrriibbuuttoorrss 111188 Article Licenses LLiicceennssee 112211 11 The City Bangalore Bengaluru (ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು)) Bangalore — — metropolitan city — — Clockwise from top: UB City, Infosys, Glass house at Lal Bagh, Vidhana Soudha, Shiva statue, Bagmane Tech Park Bengaluru (ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು)) Location of Bengaluru (ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು)) in Karnataka and India Coordinates 12°58′′00″″N 77°34′′00″″EE Country India Region Bayaluseeme Bangalore 22 State Karnataka District(s) Bangalore Urban [1][1] Mayor Sharadamma [2][2] Commissioner Shankarlinge Gowda [3][3] Population 8425970 (3rd) (2011) •• Density •• 11371 /km22 (29451 /sq mi) [4][4] •• Metro •• 8499399 (5th) (2011) Time zone IST (UTC+05:30) [5][5] Area 741.0 square kilometres (286.1 sq mi) •• Elevation •• 920 metres (3020 ft) [6][6] Website Bengaluru ? Bangalore English pronunciation: / / ˈˈbæŋɡəɡəllɔəɔər, bæŋɡəˈllɔəɔər/, also called Bengaluru (Kannada: ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು,, Bengaḷūru [[ˈˈbeŋɡəɭ uuːːru]ru] (( listen)) is the capital of the Indian state of Karnataka. -

Financial Results – Consolidated

SASKEN COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGIES LIMITED 139/25, RING ROAD, DOMLUR, BANGALORE 560 071 AUDITED CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL RESULTS FOR THE QUARTER AND YEAR ENDED MARCH 31, 2013 (Rs. in Lakhs) PART I Quarter ended Year ended Sl. No. Particulars March 31, December 31, March 31, March 31, March 31, 2013 2012 2012 2013 2012 1 Net Sales/Income from Operations 11,332.25 11,675.89 13,027.38 47,483.08 51,995.83 2 Expenditure a. Cost of materials consumed 2.01 3.38 149.30 57.83 380.06 b. Purchases of stock-in-trade 7.60 - 54.73 7.60 54.73 c. Changes in work-in-progress and stock-in-trade (80.68) (26.57) (50.03) (74.43) 39.82 d. Employee benefit expense 7,614.78 7,772.17 7,816.47 32,431.63 33,281.38 e. Depreciation & amortisation expense 538.65 608.11 513.62 1,941.45 2,235.43 f. Other expenses 2,530.74 2,637.60 2,521.80 10,869.12 10,590.25 Total 10,613.10 10,994.69 11,005.89 45,233.20 46,581.67 Profit/(Loss) from Operations before Other Income, Finance costs and 3 719.15 681.20 2,021.49 2,249.88 5,414.16 Exceptional Items (1-2) 4 Other Income 96.41 540.32 334.74 1,764.33 2,640.99 5 Profit before finance costs and Exceptional Items (3+4) 815.56 1,221.52 2,356.23 4,014.21 8,055.15 6 Finance costs 8.39 9.80 13.34 41.34 60.36 7 Profit after finance costs but before Exceptional Items (5-6) 807.17 1,211.72 2,342.89 3,972.87 7,994.79 8 Exceptional items - - - - - 9 Profit from Ordinary Activities before tax (7-8) 807.17 1,211.72 2,342.89 3,972.87 7,994.79 10 Tax expense 104.86 160.23 569.38 776.94 1,593.99 11 Net Profit from Ordinary Activities after tax (9-10) -

Assetz Titan APG Abode Homes Pvt. Ltd. Environment Clearance Page

Assetz Titan APG Abode Homes Pvt. Ltd. FORM-1 A 1. LAND ENVIRONMENT (Attach panoramic view of the project site and the vicinity) 1.1. Will the existing land-use get significantly altered from the project that is not consistent with the surroundings? (Proposed land-use must conform to the approved Master Plan / Development Plan of the area. Change of land-use if any and the statutory approval from the competent authority be submitted). Attach Maps of (i) site location, (ii) surrounding features of the proposed site (within 500 meters) and (iii) the site (indicating levels & contours) to appropriate scales. If not available attach only conceptual plans. Fig: Location Map Environment Clearance Page | 1 Assetz Titan APG Abode Homes Pvt. Ltd. Fig: Extract from BDA Master Plan 2015 Showing Proposed Project Site The project site can be accessed from T C Palya Main Road off NH 4 and from Ramamurthy Nagar off Outer Ring Road. The proposed project site is abutting a proposed 24m wide Road (T C Palya Main Road) Figure shows the project site overlapped on the BDA Revised Master Plan 2015 of Bangalore City. The land-use of proposed project site is earmarked as Residential. The land use of the part of the proposed project site is Public and Semi Public, where residential activity is permitted. Environment Clearance Page | 2 Assetz Titan APG Abode Homes Pvt. Ltd. Fig: Google Image of the Project Site Schedule of the Proposed Property East : 24m Road West : Private Property (Kristu Jothi College) North : Private Property South : T C Palya Main Road and Private Property The proposed project site is abutting 24m wide T C Palya Main Road on to the South and East, Kristu Jothi College on the West and Private property on the North. -

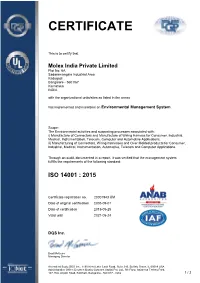

20001943 UM Date of Original Certification 2005-09-01 Date of Certification 2018-05-25 Valid Until 2021-05-24

CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Molex India Private Limited Plot No. 6A Sadaramangala Industrial Area Kadugodi Bangalore - 560 067 Karnataka INDIA with the organizational units/sites as listed in the annex has implemented and maintains an Environmental Management System. Scope: The Environmental activities and supporting processes associated with: i) Manufacture of Connectors and Manufacture of Wiring Harness for Consumer, Industrial, Medical, Instrumentation, Telecom, Computer and Automotive Applications. ii) Manufacturing of Connectors, Wiring harnesses and Over Molded products for Consumer, Industrial, Medical, Instrumentation, Automotive, Telecom and Computer Applications. Through an audit, documented in a report, it was verified that the management system fulfills the requirements of the following standard: ISO 14001 : 2015 Certificate registration no. 20001943 UM Date of original certification 2005-09-01 Date of certification 2018-05-25 Valid until 2021-05-24 DQS Inc. Brad McGuire Managing Director Accredited Body: DQS Inc., 1130 West Lake Cook Road, Suite 340, Buffalo Grove, IL 60089 USA Administrative Office: Deutsch Quality Systems (India) Pvt. Ltd., 5th Floor, Anjaneya Techno Park, 147, HAL Airport Road, Kodihalli, Bangalore - 560 017 - India 1 / 2 Annex to certificate Registration No. 20001943 UM Molex India Private Limited Plot No. 6A Sadaramangala Industrial Area Kadugodi Bangalore - 560 067 Karnataka INDIA Business Location Scope Relation # 20006122 Molex India Private Limited Assembly of Electronic Connectors Unit - 2, Plot # 2A2 and Wiring Harness. Devasandra Industrial Area Whitefield Main Road Mahadevapura Post Bangalore – 560 048 Karnataka INDIA 20001945 Molex (India) Private Limited The Environmental activities and C 7 & 8, G.I.D.C. Electronics Estate supporting processes associated with K- Road, Sector 25 the Manufacture of Consumer, Gandhinagar – 382 044 Industrial, Medical, Instrumentation, Gujarat Telecom, Computer and Automotive INDIA Connectors. -

Pourakarmika Details

ಬೃಹ ೆ೦ಗಳರು ಮಾನಗರ ಾೆ BRUHAT BANGALORE MAHANAGARA PALIKE POURAKARMIKA DETAILS Ward No:100 Sl Pourakarm Date of Name / Employee Type / Gender PF NO ESIC No Designation Photo No ika Reg No joining Address Emp.No PENCHALAMMA / Contract 1 71005967 01/01/1997 h 38 main road shivanagar Female 1083 5030979042 / 0 bangalore 10 ROOPA / Contract 2 71005985 01/01/1996 18 khb Qtrs arundatinagar Female 1084 5020979049 / 0 srirampura bangalore 21 NAGALAKSHMI / Contract 3 71006006 01/01/1996 105 3rd cross arundatinagar Female 1086 5020979055 / 0 srirampur bangalore 21 ANJINAMMA / NO 1514 2nd main Contract 4 71006317 01/01/1996 Female 1106 5020979056 sannakkibayalu kamakshipalya / 0 bangalore 560079 VENKATALAKSHMI / no 19 2 khb quarters Contract 5 71006322 01/01/1996 Female 1105 5020979058 arundhatinagar srirampuram / 0 bangalore 560021 KASTHURI. L / No203, 3rd cross, Contract 6 71006347 01/01/1996 Female 1085 5342325968 Near Govt. school / 0 kurubarahalli, Bangalore-560086 MANGAMMA / No. 357, J C nagar Slum, Contract 7 71006354 01/01/1996 Female 1099 5020979048 Basaveshwaranagar / 0 Bangalore-560079 NAGAMMA / No. 648, 1st cross, Contract 8 71006359 01/01/1996 Female 1087 5020979052 Indiranagar,Rajajinagar / 0 Bangalore-560010 NAGAMMA / No. 648, 1st cross, Contract 9 71006362 01/01/1996 Female 1087 5020979052 Indiranagar,Rajajinagar / 0 Bangalore-560010 NAGAMMA / No. 648, 1st cross, Contract 10 71006365 01/01/1996 Female 1087 5020979052 Indiranagar,Rajajinagar / 0 Bangalore-560010 1 Report Generation on 7/12/2017 12:13:39 PM ಬೃಹ ೆ೦ಗಳರು ಮಾನಗರ ಾೆ BRUHAT BANGALORE MAHANAGARA PALIKE POURAKARMIKA DETAILS Ward No:100 Sl Pourakarm Date of Name / Employee Type / Gender PF NO ESIC No Designation Photo No ika Reg No joining Address Emp.No NAGAMMA / No. -

Lkaldfrd CULTURAL Leca/K RELATIONS Ifj"Kn~

INDIAN Hkkjrh; ` COUNCIL FOR lkaLdfrd CULTURAL lEca/k RELATIONS ifj"kn~ SCHOLARSHIPS FOR FOREIGN NATIONALS Name of Scholarship Scheme AZAD BHAVAN, INDRAPRASTHA ESTATE, NEW DELHI-110 002 TEL: 23379309, 23379310, 23379315, Fax: 00-91-11-23378783, 23378639, 23378647, 23370732 Website : http://www.iccrindia.org Email: [email protected] - 1 - GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS TO APPLICANTS 1) Five complete sets of application forms are to be submitted to the Indian Mission. 2) Candidate should clearly mention the course and university to which he/she is seeking admission. The applicants are advised to go through the “Universities Handbook” available with our Mission before giving these details. ICCR would not be able to entertain a subsequent change in course of study or University once admission of a scholar is confirmed and the scholar has arrived to join the course. 3) Certified copies of all documents should be accompanied with English translations. A syllabus of the last qualifying exam application. NOTE: a) Students applying for doctoral/post doctoral courses or architecture should include a synopsis of the proposed area of research. b) Students wishing to study performing arts should, if possible, enclose Video/audio cassettes of their recorded performances. 4) Candidates must pass English Proficiency Test conducted by Indian Mission. 5) ICCR will not entertain applications which are sent to ICCR directly by the students or which are sent by local Embassy/High Commissions in New Delhi. 6) Priority will be given to students who have never studied in India before. 7) No application will be accepted for admission to courses in medicine or dentistry. 8) Candidates may note that Indian universities/educational institutions are autonomous and independent and hence have their own eligibility criteria.