An Archaeological Strategy for the Historic Centre of St Albans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hertfordshire Archaeology and History Hertfordshire Archaeology And

Hertfordshire Archaeology and History Hertfordshire Archaeology and History is the Society’s Journal. It is published in partnership with the East Herts Archaeological Society. We will have stock of the current (Vol. 17) and recent editions (Vols. 12-16) on sale at the conference at the following prices: • Volume 17: £12.00 as a ‘conference special’ price (normally £20.00); £5.00 to SAHAAS members • Volume 14 combined with the Sopwell Excavation Supplement: £7.00, or £5.00 each when sold separately • All other volumes: £5.00 Older volumes are also available at £5.00. If you see any of interest in the following contents listing, please email [email protected] by 11am on Friday 28 June and we will ensure stock is available at the conference to peruse and purchase. Please note: copies of some older volumes may be ex libris but otherwise in good condition. Volume 11 is out of stock. Copies of the Supplement to Volume 15 will not be available at the conference. If you have any general questions about the Journal, please email Christine McDermott via [email protected]. June 2019 Herts Archaeology and History - list of articles Please note: Volume 11 is out of stock; the Supplement to Volume 15 is not available at the conference Title Authors Pub Date Vol Pages Two Prehistoric Axes from Welwyn Garden City Fitzpatrick-Matthews, K 2009-15 17 1-5 A Late Bronze Age & Medieval site at Stocks Golf Hunn, J 2009-15 17 7-34 Course, Aldbury A Middle Iron Age Roundhouse and later Remains Grassam, A 2009-15 17 35-54 at Manor Estate, -

St Albans and District Tourism Profile and Strategic Action Plan

St Albans and District Tourism Profile and Strategic Action Plan Prepared by Planning Solutions Consulting Ltd March 2021 www.pslplan.co.uk 1 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Setting the Scene 3. Support infrastructure and marketing 4. Business survey 5. Benchmarking: comparator review 6. Tourism profile: challenges and priorities 7. Strategic priorities and actions Key contact David Howells Planning Solutions Consulting Limited 9 Leigh Road, Havant, Hampshire PO9 2ES 07969 788 835 [email protected] www.pslplan.co.uk 2 1. Introduction 1.1 Background This report sets out a Tourism Profile for St Albans and District and outlines strategic priorities and actions to develop the visitor economy in the city and the wider district. The aim is to deliver a comprehensive Tourism Strategic Action Plan for St Albans to provide a roadmap for the district to move forward as a visitor destination with the engagement and support of key stakeholders. Delivery of the plan will be a collaborative process involving key stakeholders representing the private and public sectors leading to deliverable actions to guide management and investment in St Albans and key performance indicators to help leverage the uniqueness of St Albans to create a credible and distinct visitor offering. Destination management and planning is a process of coordinating the management of all aspects of a destination that contribute to a visitor’s experience, taking account of the needs of the visitors themselves, local residents, businesses and the environment. It is a systematic and holistic approach to making a visitor destination work efficiently and effectively so the benefits of tourism can be maximised and any negative impacts minimised. -

The Art of Great Hospitality

The Art of Great Hospitality 2018 Britain’s leading luxury and boutique hotel collection. Pride of Britain Hotel of the Year 2017 Rockliffe Hall, The North. Page 108 Bookings & Enquiries - Call FREEPHONE: 0800 089 3929 - Book online: www.prideofbritainhotels.com - Phone from outside the UK: +44 1666 824 666 - Call the hotel direct GDS Codes for Travel Agents All Pride of Britain member hotels that are not contracted to other consortia can be found on Amadeus, Worldspan, Sabre and Galileo under the prefix YX. Stay up to date with the latest news and offers Join us on Follow us on Watch us on Find us on Follow us on Follow us on FACEBOOK TWITTER YOUTUBE GOOGLE+ PINTEREST INSTAGRAM 01 5698.002_ClassicSinglePage_ART.indd 3 29/08/2017 15:03 London The Cotswolds The Arch London 04 Barnsley House Hotel and Spa 68 Introduction The Capital 06 Calcot & Spa 70 The Goring 08 Ellenborough Park 72 Welcome to our collection of independent 124 Pride of Britain Farncombe Estate 74 luxury and boutique hotels throughout this hotel locations The South East Lucknam Park 76 beautiful country. Thirty six years since Pride Bailiffscourt Hotel and Spa 14 Whatley Manor 78 of Britain was formed, our mission remains Numbers relate to page numbers where Bedford Lodge 16 unchanged: to effectively market and support hotels appear Gravetye Manor 18 Central England a collection of the finest privately owned hotels Hartwell House and Spa 20 Hambleton Hall 84 in Britain. 118 122 Maison Talbooth 22 Kilworth House Hotel and Theatre 86 Each hotel is unique but all are run by people Ockenden Manor Hotel and Spa 24 Stapleford Park 88 with a passion for delivering great hospitality, Sopwell House 26 The North so if you have enjoyed any of our member South Lodge 28 properties already we feel sure you will like the Armathwaite Hall Hotel and Spa 94 120 The Montagu Arms 30 others too. -

Planning and Tree Works Applications and Decisions

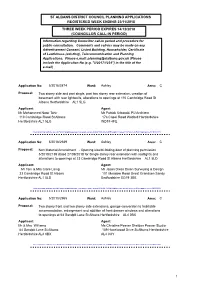

ST ALBANS DISTRICT COUNCIL PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED WEEK ENDING 23/11/2018 THREE WEEK PERIOD EXPIRES 14/12/2018 (COUNCILLOR CALL-IN PERIOD) Information regarding Councillor call-in period and procedure for public consultation. Comments and call-ins may be made on any Advertisement Consent, Listed Building, Householder, Certificate of Lawfulness (existing), Telecommunication and Planning Applications. Please e.mail: [email protected] (Please include the Application No (e.g. "5/2017/1234") in the title of the e.mail) Application No: 5/2018/2874 Ward: Ashley Area: C Proposal: Two storey side and part single, part two storey rear extension, creation of basement with rear lightwells, alterations to openings at 110 Cambridge Road St Albans Hertfordshire AL1 5LG Applicant: Agent: Mr Mohammed Nasir Tahir Mr Patrick Urbanski PU Architect 110 Cambridge Road St Albans 17a Capel Road Watford Hertfordshire Hertfordshire AL1 5LG WD19 4FE http://planning.stalbans.gov.uk/Planning/lg/dialog.page?org.apache.shale.dialog.DIALOG_NAME=gfplanningsearch&Param=lg.Planning&ref_no=5/2018/2874 Application No: 5/2018/2939 Ward: Ashley Area: C Proposal: Non Material Amendment - Opening size/bi-folding door of planning permission 5/2018/2139 dated 27/09/2018 for Single storey rear extension with rooflights and alterations to openings at 33 Cambridge Road St Albans Hertfordshire AL1 5LD Applicant: Agent: Mr Tom & Mrs Clare Laing Mr Jason Dixon Dixon Surveying & Design 33 Cambridge Road St Albans 101 Meadow Road Great Grandsen Sandy Hertfordshire AL1 -

The Cocktail Lounge Menu

THE COCKTAIL LOUNGE MENU Take time to sample our delicious cocktails at what we consider to be the finest Cocktail Lounge in Hertfordshire. The modern Cocktail Lounge is a very comfortable space for meetings, catching up with friends or just relaxing. It’s the perfect place to enjoy a cold beverage or Afternoon Tea by day, or a classic cocktail by night. We also offer free WiFi, enabling you to work, shop and stay connected online. 1 Food served Sunday to Thursday 12.00pm to 11.00pm, Friday and Saturday 12.00pm to 1.00am SHARING PLATES INDIVIDUAL PLATE 5.95 SELECT THREE 14.95 SELECT SIX 26.95 ITALIAN OLIVES (VE) HUMMUS & PITTA BREAD (VE) (GL,SS) AVOCADO, MANGO & QUINOA MINI TACOS, CHIPOTLE MAYONNAISE (V) (EG) TOMATO ARANCINI, AIOLI (V) (DA,EG,GL) GRILLED TIGER PRAWNS, COCKTAIL DIP (CR,EG,SD) MINI BEEF SLIDER, TOMATO RELISH, SMOKED APPLEWOOD, TRUFFLE MAYONNAISE (DA,EG,GL,MU) PERI PERI CHICKEN SKEWERS, CHIVE CRÈME FRAÎCHE (DA) CRISPY WHITE-BAIT, HARISSA MAYONNAISE, COCONUT & CORIANDER SALAD (EG,FI,GL) TRUFFLE FRIES (V) SWEET POTATO FRIES (V) SOPWELL SELECTION STARTER MAIN CLASSIC CAESAR SALAD (DA,EG,FI,GL,SD) 7.50 11.50 Baby gem lettuce, anchovies, parmesan, garlic croutons WITH GRILLED CHICKEN or 9.50 14.50 WITH SMOKED SALMON (FI) or 11.50 14.50 ENGLISH CURED HAM & 9.50 CANTALOUPE MELON (MU,SD) Toasted pumpkin seed dressing SOPWELL HOUSE BURGER (DA,EG,GL,MU,SD,S0) 16.50 Dedham Vale beef burger, smoked apple wood cheese, streaky bacon, bbq sauce, brioche bun, fries VEGAN BURGER (VE) (GL,SD) 14.50 Avocado & chilli crush, beetroot remoulade, grilled sourdough bun, fries 2 SANDWICHES & WRAPS SOPWELL CLUB SANDWICH (DA,EG,GL,SD) 13.50 Grilled chicken, streaky bacon, iceberg lettuce, mayonnaise, tomato, gherkins, toasted white or wholemeal bread All below sandwiches are served with house salad & kettle crisps. -

NEWSLETTER Founded 1845 No

STALBANS AND HERTFORDSHIRE ARCHITECTURALAND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY www.stalbanshistory.org NEWSLETTER Founded 1845 No. 159 November 2005 Registered Charity No. 226912 Hon. Sec: Bryan Hanlon, 24 Monks Horton Way, St Albans AL1 4HA SAHAAS H O S T S 2005 HALH SY M P O S I U M IN T H I S I S S U E Each year one of the members of the in stagecoach design, such as new Trifels revisited 2 Hertfordshire Association for Local springs. Improvements at 2 History hosts a symposium on a In the pre-lunch spot we had our very Sopwell selected topic agreed with HALH. own David Dean on ‘St Albans: inns and New Members’ party 2 This year, for the first time since 1996, the thoroughfare town’. Although this Second hand books 2 SAHAAS were asked to act as hosts. will have been familiar material to many The 1996 symposium was highly SAHAAS members he brought alive St Obituary: Anne Kaloczi 3 successful so a hard act to follow. Albans’ history in a very vivid way to Obituary: Dr John Lunn 3 other attendees. Our thanks go to the organising Field names of 4 committee (David Dean, Clare Ellis and After an excellent lunch, most efficiently Verulamium Park Pat Howe), to Ann Dean and Doreen organised by the caterers assisted by St Pancras Chambers 4 Bratby and their catering our own band of ladies, we heard from team (Margaret Dr Alan Thomson (Lecturer in History Archaeology and Local 5 Amsdon, Diane at the University of Hertfordshire) on History Group Ayerst, Rita ‘Kings, carts and composition: St Amphibalus Shrine 5 Cadish, Gill Charles, the early Stuarts and Symposium Irene Cowan and Hertfordshire roads’. -

Hawkins Jillian

UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES The significance of the place-name element *funta in the early middle ages. JILLIAN PATRICIA HAWKINS Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2011 UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The significance of the place-name element *funta in the early middle ages. Jillian Patricia Hawkins The Old English place-name element *funta derives from Late Latin fontāna, “spring”, and is found today in 21 place-names in England. It is one of a small group of such Latin-derived elements, which testify to a strand of linguistic continuity between Roman Britain and early Anglo- Saxon England. *funta has never previously been the subject of this type of detailed study. The continued use of the element indicates that it had a special significance in the interaction, during the fifth and sixth centuries, between speakers of British Latin and speakers of Old English, and this study sets out to assess this significance by examining the composition of each name and the area around each *funta site. Any combined element is always Old English. The distribution of the element is in the central part of the south- east lowland region of England. It does not occur in East Anglia, East Kent, west of Warwickshire or mid-Wiltshire or north of Peterborough. Seven of the places whose names contain the element occur singly, the remaining fourteen appearing to lie in groups. The areas where *funta names occur may also have other pre-English names close by. -

Handlist of Maps, Plans, Illustrations and Other Large-Format Single-Sheet Material in the Society's Library

Handlist of maps, plans, illustrations and other large-format single-sheet material in the Society’s library This is the fourth edition of the Handlist covering the Society’s map collection. The key updates since the last edition are the inclusion of new digital and printed copies of Benjamin Hare’s 1634 map of the town. Our extensive and eclectic collection also includes architectural drawings, auction notices and posters. The earliest map is Hare’s 1634 map referred to above; we have a unique set of copies of three St Albans parish maps from around 1810; and copies of the 1879 1:500 scale Ordnance Survey maps of St Albans town centre. Some material has not yet been included in this listing. For example, we have digital copies of the early Victorian tithe maps for the four St Albans parishes as well as Sandridge. We also have a digital copy of a rare map of the town in the late 1850s. All are available to view on computer. The listing was collated by Library volunteers Tony Cooper, Frank Iddiols and Jonathan Mein. If you want to know more about the library then please have a look at the society’s web site or contact the library team by email. Donald Munro Society Librarian April 2018 [email protected] www.stalbanshistory.org www.stalbanshistory.org Handlist of maps, illustrations and over-sized material etc. in the Society's Library April 2018 Publisher / Author Title Type Scale Date Location Notes - St Albans pageant, 1948 Poster - 1948 A1/1/a 6 copies, 3 damaged Poster advertising London-Taunton stagecoach Photocopy; laminated -

The Impact of Agricultural Depression and Land

THE IMPACT OF AGRICULTURAL DEPRESSION AND LAND OWNERSHIP CHANGE ON THE COUNTY OF HERTFORDSHIRE, c.1870-1914 Julie Patricia Moore Submitted to the University of Hertfordshire in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of PhD September 2010 2 ABSTRACT The focus of this research has been on how the county of Hertfordshire negotiated the economic, social and political changes of the late nineteenth century. A rural county sitting within just twenty miles of the nation’s capital, Hertfordshire experienced agricultural depression and a falling rural population, whilst at the same time seeing the arrival of growing numbers of wealthy, professional people whose economic focus was on London but who sought their own little patch of the rural experience. The question of just what constituted that rural experience was played out in the local newspapers and these give a valuable insight into how the farmers of the county sought to establish their own claim to be at the heart of the rural, in the face of an alternative interpretation which was grounded in urban assumptions of the social value of the countryside as the stable heart of the nation. The widening of the franchise, increased levels of food imports and fears over the depopulation of the villages reduced the influence of farmers in directing the debate over the future of the countryside. This study is unusual in that it builds a comprehensive picture of how agricultural depression was experienced in one farming community, before considering how farmers’ attempts to claim ownership of the ‘special’ place of the rural were unsuccessful economically, socially and politically. -

The Watermeadow Walk Sopwell House Hotel Park Street: the Falcon and the Overdraught Public Houses

Teas, buns, pints and pies: Clock Tower: The Boot and The Fleur de Lys Public Houses, plus numerous cafés and restaurants. Ver ValleY WALK 7 Verulamium Park: The Fighting Cocks Public House, Café at the Abbey, plus ice-cream vans. Holywell Hill: The Peahen, Duke of Marlborough and The White Hart Public Houses plus Café Rouge restaurant and café. The Watermeadow Walk Sopwell House Hotel Park Street: The Falcon and The Overdraught Public Houses. Explore the beautiful rolling countryside How to get there: of this river valley By road: The Clock Tower is situated in Market Place, St Albans. Leave Junction 21a of the M25 or Junction 6 of the M1 and take the A405, followed by the A5183 direction St Albans. There are several car parks within the city centre but the closest are at Westminster Lodge and Christopher Place. For more information on car parks see www.stalbans.gov.uk By public transport: St Albans is served by transport links from London as well as surrounding villages and towns. Regular trains run from London to the City Station, as well as the Abbey Station from Watford, for further details visit www.nationalrail.co.uk. For details of coach and bus services contact Traveline on 0871 200 2233 or visit www.intalink.org.uk Parts of this walk can be muddy or wet underfoot. This is one of a series of 8 circular walks on the River Ver and part of the 17 mile long linear, River Ver Trail. You can also use the OS Explorer Map 182 to find your way around the Valley. -

St Albans District Council Planning Applications Registered Week Ending 28Th April 2017 Three Week Period Expires 19Th May 2017 (Councillor Call-In Period)

ST ALBANS DISTRICT COUNCIL PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED WEEK ENDING 28TH APRIL 2017 THREE WEEK PERIOD EXPIRES 19TH MAY 2017 (COUNCILLOR CALL-IN PERIOD) Information regarding Councillor call-in period and procedure for public consultation. Comments and call-ins may be made on any Advertisement Consent, Listed Building, Conservation Area, Householder, Certificate of Lawfulness (existing), Telecommunication and Planning Applications please e.mail: [email protected] (Please include the Application No (e.g. "5/2009/1234") in the title of the e.mail) Application No: 5/2017/0988 Ward: Ashley Area: C Proposal: Two storey side and part single, part two storey rear extensions following demolition of existing garage, new patio and roof canopy to rear elevation, demolition of boundary wall and lowering level of front garden area beneath bay window at 1 Ely Road St Albans Hertfordshire AL1 5NA Applicant: Agent: Mr & Mrs Hodge 1 Ely Road St Albans Mr Mark Biddiss 36 Charlesworth Close Hertfordshire AL1 5NA Hemel Hempstead Hertfordshire HP3 9EW http://planning.stalbans.gov.uk/Planning/lg/dialog.page?org.apache.shale.dialog.DIALOG_NAME=gfplanningsearch&Param=lg.Planning&ref_no=5/2017/0988 Application No: 5/2017/1052 Ward: Ashley Area: C Proposal: Single storey front extension, first floor side extension and pitched roof to porch at 49 Cedarwood Drive St Albans Hertfordshire AL4 0DN Applicant: Agent: Mr Steven Johnson 49 Cedarwood C J Cowie Associates Mr Chris Cowie 10 Drive St Albans Hertfordshire AL4 0DN Regent Close Kings Langley Hertfordshire -

Hertfordshire Archaeology Index to Vols

Hertfordshire Archaeology Index to vols. Volume 1, 1968 Foreword 1 The Date of Saint Alban John Morris, B.A., Ph.D. 9 Excavations in Verulam Hills Field, St Albans, Ilid E Anthony, M.A., Ph.D., F.S.A. 1963-4 51 Investigation of a Belgic Occupation Site at A G Rook, B.Sc. Crookhams, Welwyn Garden City 66 The Ermine Street at Cheshunt, Herts. G R Gillam 68 Sidelights on Brasses in Herts. Churches, XXXI: R J Busby Furneaux Pelham 76 The Peryents of Hertfordshire Henry W Gray 89 Decorated Brick Window Lintels Gordon Moodey 92 The Building of St Albans Town Hall, 1829-31 H C F Lansberry, M.A., Ph.D. 98 Some Evidence of Two Mesolithic Sites at A V B Gibson Bishop's Stortford 103 A late Bronze Age and Romano-British Site at Wing-Commander T W Ellcock, Thorley Hill M.B.E. 110 Hertfordshire Drawings of Thomas Fisher Lieut-Col. J H Busby, M.B.E. 117 A Romano-British Well at Welwyn A G Rook, B.Sc. 119 A Neolithic Axe from Redbourn F D Stageman 120 An Early Vestry at St Stephen's Church, St Peter Curnow, B.Sc., F.S.A. Albans 121 A Belgic Ditched Enclosure at Nutfield, Welwyn A G Rook, B.Sc. Garden City 122 Graffiti at the Old Tannery House, Whitwell Doris W J Baker, M.A. 124 Further Finds of Medieval Pottery from Elstree: D F Renn, F.S.A. with a Survey of Unglazed Thumb-pressed Jugs 127 Medieval Pottery from High Cross and Potters Gordon Moodey Green 132 The Sixteenth-century Cottages, now Raban Gordon Moodey House, Baldock 139 The Kentish Family Monument in St Mary Lieut-Col.