India's Fight Against Health Emergencies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jingoism Will Not Be Able to Surmount the Deep Discontent, Says Manish Tewari

Interview Jingoism will not be able to surmount the deep discontent, says Manish Tewari SMITA GUPTA Former Union Minister Manish Tewari. FIle photo: K. Murali Kumar The Balakot bombings that followed the terror strike in Pulwama have given an edge to the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP)’s election plank of muscular nationalism and has, for the moment, at least, taken the spotlight off the failures of the Narendra Modi government. In this interview, former Information and Broadcasting Minister Manish Tewari — who is also a Distinguished Senior Fellow at The Atlantic Council’s South Asia Centre — talks to Smita Gupta, Senior Fellow, The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy, New Delhi,about the impact of the BJP’s nationalism card in the upcoming general elections, the role of the media in amplifying the BJP’s message, why the Congress has been circumspect on the subject and whether it is appropriate to use national security as an election issue. He also points out that while the Balakot bombings appeased public opinion to some extent, it has also created a new strategic dynamic on the sub-continent that will make it tougher for future governments to deal with incidents of terror. Excerpts: ill the Pulwama attack, the opposition’s narrative of unemployment being at a 45-year high, rural distress, the negative impact of T demonetisation, etc appeared to be gaining ground in the public discourse. But after the Balakot air strikes, that narrative appears to have changed. Pakistan, war, terrorism appear to be the preferred subjects. Does this not give the advantage back to the BJP? There are two parallel discourses: there is a discourse in the ether which is about Pakistan, Kashmir and war hanging low over the subcontinent. -

Events; Appointments; Etc - August 2013

Events; Appointments; Etc - August 2013 BACK APPOINTED; ELECTED; Etc. Hassan Rowhani: He has been elected as the President of Iran. Raghuram Rajan: Chief Economic Adviser to UPA government, he has been appointed as the Governor of Reserve Bank Of India (RBI). Dilip Trivedi: Senior IPS officer, he has been appointed as the Chief of the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF). DISTINGUISHED VISITORS G.L. Peiris: External Affairs Minister of Sri Lanka. He came to invite Prime Minister Manmohan Singh for the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meet in Colombo in November. Prime Minister Singh, during his talk with Mr Peiris, asked Sri Lanka to stand by its commitment not to dilute the 13th Amendment on devolution of powers to the provinces and sought an early repatriation of Indian fishermen presently in the custody of the Lankan authorities. Mohammad Karim Khalili: Vice President o Afghanistan. During his three-day visit security issues and trade and other bilateral issues were discussed. Nuri al-Maliki: Prime Minister of Iraq. The visit was the first high-level bilateral trip in 38 years. Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had visited Iraq in 1975. Maliki’s trip saw India and Iraq sign an agreement on energy cooperation. Tshering Tobgay: Prime Minister of Bhutan. This was his first overseas visit after assuming office in July 2013. He briefed New Delhi on the talks between his country and China over their boundary dispute, which has strategic implications for India’s security. DIED Pandit Raghunath Panigrahi: Eminent Indian classical singer and music director from Odisha, better known as a noted vocalist of Jayadeva’s ‘Gita Govind’, he died on 25 August 2013. -

Standing Committee on External Affairs (2012-2013)

STANDING COMMITTEE 18 ON EXTERNAL AFFAIRS (2012-2013) FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA MINISTRY OF OVERSEAS INDIAN AFFAIRS [Action Taken on the recommendations contained in the Thirteenth Report (15th Lok Sabha) on Demands for Grants of the Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs for the year 2012-13] EIGHTEENTH REPORT LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI March, 2013/Phalguna, 1934 (Saka) EIGHTEENTH REPORT STANDING COMMITTEE ON EXTERNAL AFFAIRS (2012-2013) (FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA) MINISTRY OF OVERSEAS INDIAN AFFAIRS [Action Taken on the observations/recommendations contained in the Thirteenth Report (15th Lok Sabha) on Demands for Grants of the Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs for the year 2012-13] Presented to Lok Sabha on14th March, 2013 Laid in Rajya Sabha on 14th March,, 2013 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI March, 2013/Phalguna,1934 (Saka) COEA NO. 101_ Price : Rs. ................. © 2013 by Lok Sabha Secretariat Published under Rule 382 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha (Thirteenth Edition) and Printed by CONTENTS PAGE COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE 2012-2013……………………… (iii) INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………… (v) Chapter I Report…………………………………………………………. 1 Chapter II Recommendations/Observations which have been accepted by the Government………………………………... 17 Chapter III Recommendations/Observations which the Committee do not desire to pursue in view of the Government’s Replies...… 27 Chapter IV Recommendations/Observations in respect of which Replies of Government have not been accepted by the Committee and require reiteration…………………………..…………… 28 Chapter V Recommendations/Observations in respect of which Final Replies of the Government are still awaited……………… 31 APPENDICES I. Minutes of the sitting of the Committee 33 held on 12.03.2013……………………………………………… II. -

Resume of Work Done by Lok Sabha

RESUME OF WORK DONE BY LOK SABHA FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA EIGHTH SESSION, 2011 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT, NEW DELHI November, 2011/Kartika, 1933 (Saka) RESUMÉ OF WORK DONE BY LOK SABHA FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA—EIGHTH SESSION 1 August, 2011 to 8 September, 2011 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI November, 2011/Kartika, 1933 (Saka) T.O. No. 3/15 LS Vol. VIII © 2011 BY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT Published under Rule 382 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha (Fourteenth Edition) and Printed by the General Manager, Government of India Press, Minto Road, New Delhi. PREFACE This Publication contains a brief resume of work done in the Fifteenth Lok Sabha during the Eighth Session i.e. from the 1 August, 2011 to 8 September, 2011. NEW DELHI; T.K. VISWANATHAN, November, 2011 Secretary-General. Kartika, 1933 (Saka) CONTENTS PAGE(S) 1. DURATION OF SESSION . 1 2. BILLS (i) Government Bills . 2 (ii) Bills referred to Standing Committees . 6 (iii) Private Members' Bills . 11 3. CALLING A TTENTION . 19 4. COMMITTEES (i) Financial Committees . 20 (ii) Standing Committees . 21 (iii) Committees other than Financial and Standing Committees . 23 5. DIVISIONS . 26 6. FINANCIAL BUSINESS General Budget . 27 7. MEMBERS ELECTED IN BYE-ELECTION . 28 8. MOTIONS (i) Motions under Rules 191 and 342 . 29 (ii) Motions under Rule 388 . 31 9. OATH/AFFIRMATION . 32 10. OBITUARY AND OTHER REFERENCES . 33 11. PAPERS LAID ON THE TABLE . 37 12. PETITIONS . 38 (iii) (iv) PAGE(S) 13. QUESTIONS (i) Starred . 39 (ii) Short Notice . 39 (iii) Unstarred . 39 (iv) Half-an-Hour Discussion . -

Standing Committee on Finance (2019-20)

10 STANDING COMMITTEE ON FINANCE (2019-20) SEVENTEENTH LOK SABHA MINISTRY OF PLANNING DEMANDS FOR GRANTS (2020-21) TENTH REPORT LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI March, 2020 / Phalguna, 1941 (Saka) TENTH REPORT STANDING COMMITTEE ON FINANCE (2019-20) (SEVENTEENTH LOK SABHA) MINISTRY OF PLANNING DEMANDS FOR GRANTS (2020-21) Presented to Lok Sabha on March, 2020 Laid in Rajya Sabha on March, 2020 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI March, 2020 / Phalguna, 1941 (Saka) CONTENTS Page Nos. COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE....................... (iii) INTRODUCTION...................................................... (iv) PART - I Chapter-I Introductory 1 Chapter-II Analysis of Demands for Grants (2020-21) 3 Chapter-III Development Monitoring And Evaluation Office (DMEO) 11 Chapter-IV Atal Innovation Mission (AIM) & Self-Employment and Talent Utilisation (SETU) 16 Chapter-V Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 19 PART - II Observations / Recommendations of the Committee 22-26 ANNEXURE Minutes of the Sittings held on 03 March, 2020 and 06 March, 2020 COMPOSITION OF STANDING COMMITTEE ON FINANCE (2019-20) Shri Jayant Sinha - Chairperson MEMBERS LOK SABHA 2. Shri S.S. Ahluwalia 3. Shri Subhash Chandra Baheria 4. Shri Vallabhaneni Balashowry 5. Shri Shrirang Appa Barne 6. Dr. Subhash Ramrao Bhamre 7. Smt. Sunita Duggal 8. Shri Gaurav Gogoi 9. Shri Sudheer Gupta 10. Smt. Darshana Vikram Jardosh 11. Shri Manoj Kishorbhai Kotak 12. Shri Pinaki Misra 13. Shri P.V Midhun Reddy 14. Prof. Saugata Roy 15. Shri Gopal Chinayya Shetty 16. Dr. (Prof.) Kirit Premjibhai Solanki 17. Shri Manish Tewari 18. Shri P. Velusamy 19. Shri Parvesh Sahib Singh Verma 20. Shri Rajesh Verma 21 Shri Giridhari Yadav RAJYA SABHA 22. -

Rajya Sabha 45

PARLIAMENT OF INDIA RAJYA SABHA 45 DEPARTMENT RELATED PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON PERSONNEL, PUBLIC GRIEVANCES, LAW AND JUSTICE FORTY FIFTH REPORT ON THE MARRIAGE LAWS (AMENDMENT) BILL, 2010 ________________________________________________________________________ (PRESENTED TO THE RAJYA SABHA ON 1ST MARCH, 2011) (LAID ON THE TABLE OF THE LOK SABHA ON 1ST MARCH, 2011) RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI MARCH, 2011 / PHALGUNA 1932 (SAKA) CS (P & L) - .... PARLIAMENT OF INDIA RAJYA SABHA DEPARTMENT RELATED PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON PERSONNEL, PUBLIC GRIEVANCES, LAW AND JUSTICE FORTY FIFTH REPORT ON THE MARRIAGE LAWS (AMENDMENT) BILL, 2010 (PRESENTED TO THE RAJYA SABHA ON 1ST MARCH, 2011) (LAID ON THE TABLE OF THE LOK SABHA ON 1ST MARCH, 2011) RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI MARCH, 2011 / PHALGUNA 1932 (SAKA) C O N T E N T S PAGES 1. COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE (i) 2. INTRODUCTION (ii)-(iii) 3. REPORT 1 - 30 * 4. RELEVANT Minutes OF THE MEETINGS OF THE COMMITTEE ….. *5. ANNEXURE – A. THE MARRIAGE LAWS (AMENDMENT) BILL, 2010 B. COMMENTS OF THE MINISTRY OF LAW AND JUSTICE (LEGISLATIVE DEPARTMENT) ON THE VIEWS/SUGGESTIONS CONTAINED IN MEMORANDA SUBMITTED BY INDIVIDUALS/ORGANISATIONS/EXPERTS ON THE PROVISIONS OF THE BILL. * To be appended at printing stage. COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE 1. Smt. Jayanthi Natarajan Chairperson RAJYA SABHA 2. Shri Shantaram Laxman Naik 3. Dr. Abhishek Manu Singhvi 4. Shri Balavant alias Bal Apte 5. Shri Ram Jethmalani 6. Shri Parimal Nathwani 7. Shri Amar Singh 8. Shri Ram Vilas Paswan 9. Shri O.T. Lepcha 10. Vacant* LOK SABHA 11. Shri N.S.V. Chitthan 12. Smt. Deepa Dasmunsi 13. -

Union Cabinet Minister, India.Pdf

India gk World gk Misc Q&A English IT Current Affairs TIH Uninon Cabinet Minister of India Sl No Portfolio Name Cabinet Minister 1 Prime Minister Minister of Atomic Energy Minister of Space Manmohan Singh Minister of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions Ministry of Planning 2 Minister of Finance P. Chidambaram 3 Minister of External Affairs Salman Khurshid 4 Minister of Home Affairs Sushil Kumar Shinde 5 Minister of Defence A. K. Antony 6 Minister of Agriculture Sharad Pawar Minister of Food Processing Industries 7 Minister of Communications and Information Technology Kapil Sibal Minister of Law and Justice 8 Minister of Human Resource Development Dr. Pallam Raju 9 Ministry of Mines Dinsha J. Patel 10 Minister of Civil Aviation Ajit Singh 11 Minister of Commerce and Industry Anand Sharma Minister of Textiles 12 Minister of Petroleum and Natural Gas Veerappa Moily 13 Minister of Rural Development Jairam Ramesh 14 Minister of Culture Chandresh Kumari Katoch 15 Minister of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation Ajay Maken 16 Minister of Water Resources Harish Rawat 17 Minister of Urban Development Kamal Nath Minister of Parliamentary Affairs 18 Minister of Overseas Indian Affairs Vayalar Ravi 19 Minister of Health and Family Welfare Ghulam Nabi Azad 20 Minister of Labour and Employment Mallikarjun Kharge 21 Minister of Road Transport and Highways Dr. C. P. Joshi Minister of Railway 22 Minister of Heavy Industries and Public Enterprises Praful Manoharbhai Patel 23 Minister of New and Renewable Energy Farooq Abdullah 24 Minister of Panchayati Raj Kishore Chandra Deo Minister of Tribal Affairs 25 Minister of Science and Technology Jaipal Reddy Minister of Earth Sciences 26 Ministry of Coal Prakash Jaiswal 27 Minister of Steel Beni Prasad Verma 28 Minister of Shipping G. -

Now, Papers to Be Laid. Shri S. Jaipal Reddy. ...(Interruptions) MADAM SPEAKER: Nothing Else Will Go on Record

> Title: Papers laid on the Table of the House by Ministers/members. MADAM SPEAKER: Now, Papers to be laid. Shri S. Jaipal Reddy. ...(Interruptions) MADAM SPEAKER: Nothing else will go on record. (Interruptions) … * THE MINISTER OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY AND MINISTER OF EARTH SCIENCES (SHRI S. JAIPAL REDDY): I beg to lay on the table:- (1) (i) A copy of the Annual Report (Hindi and English versions) of the Technology Development Board, New Delhi, for the year 2010-2011, along with Audited Accounts. (ii) Statement regarding Review (Hindi and English versions) by the Government of the working of the Technology Development Board, New Delhi, for the year 2010-2011. (2) Statement (Hindi and English versions) showing reasons for delay in laying the papers mentioned at (1) above. [Placed in Library. See No. LT 9616/15/13] ...(Interruptions) THE MINISTER OF HEAVY INDUSTRIES AND PUBLIC ENTERPRISES (SHRI PRAFUL PATEL): I beg to lay on the Table:- (1) A copy each of the following papers (Hindi and English versions) under sub- section (1) of Section 619A of the Companies Act, 1956:- (a) Annual Report of the Tungabhadra Steel Products Limited, Hospet, for the year 2011-2012, alongwith Audited Accounts and comments of the Comptroller and Auditor General thereon. [Placed in Library. See No. LT 9617/15/13] (b) Annual Report of the Richardson & Cruddas (1972) Limited, Mumbai, for the year 2011-2012, alongwith Audited Accounts and comments of the Comptroller and Auditor General thereon. (2) Two statements (Hindi and English versions) showing reasons for delay in laying the papers mentioned at (1) above. -

As on 30-09-2020

GRAPH-PERCENTAGE UTILISATION OF FUNDS UPTO 30.09.2020 SITTING/EX MPs BOTH LS AND RS SINCE INCEPTION(1993-94)(ITEM 2.1) 1 2 5 100.00 9 9 . 3 5 9 7 . 3 4 9 7 . 3 0 9 6 . 8 5 1 0 0 9 5 . 4 5 9 4 . 4 7 9 4 . 1 4 9 4 . 1 0 9 3 . 9 5 9 3 . 6 9 9 2 . 4 9 9 2 . 1 5 9 1 . 8 8 9 1 . 7 6 9 1 . 5 0 8 6 . 5 9 75 % UTILISATION % 50 25 0 ITEM 1.1 : INSTALLMENTS DUE - 16TH LS MPs As on 30/09/2020 SN Districts 2017-18 (1st) 2017-18 (2nd) 2018-19 (1st) 2018-19(2nd) Total 1 Amritsar-Gurjeet Singh ----0 2 Bathinda-Smt. Harsimrat Kaur Badal ----0 3 Faridkot-Sh. Sadhu Singh (SC) ----0 4 Ferozepur-Sh. Sher Singh Ghubaya ----0 Gurdaspur- Sunil Jakhar 5 --112 6 Hoshiarpur-Sh. Vijay Sampla (SC) ---11 7 Jalandhar-Sh. Santokh Singh Chaudhary ----0 8 Ludhiana-Sh. Ravneet Singh Bittu ----0 9 Patiala-Sh. Dharam Vira Gandhi ----0 10 Sangrur-Sh. Bhagwant Mann ----0 11 Ludhiana-Sh. Harinder Singh khalsa( Fatehgarh Sahib) ----0 12 Ajitgarh-Sh.Prem Singh Chandumajra (Anandpur Sahib) ----0 13 Tarn Taran-Sh. Ranjit Singh Brahmpura (Khadoor Sahib) ----0 Grand Total 00123 MPR 30-09-2020.xls ITEM 1.1 ITEM 1.1 A INSTALLMENTS DUE- 17TH LS MPs As on 30/09/2020 SN Nodal District 2019-20 (1st) 2019-20(2nd) Total 1 Amritsar-Sh. Gurjeet Singh Aujla 011 2 Bathinda-Smt. -

Science and Technology on Environment: Lok Sabha 2012-13

Science and Technology on Environment: Lok Sabha 2012-13 Q. No. Q. Type Date Ans by Ministry Members Title of the Subject Specific Political State Questions Party Representative 29.03.2012 Environmental Science and Sardar Partap Singh Mapping of Education, NGOs and 2533 Unstarred Technology Bajwa Himalayan Region Media INC Punjab 2750 29.03.2012 Science and Shri Ashok Tanwar Status of Bio- INC Haryana Unstarred Technology Diesel Research Agriculture Climate Change and Meteorology Energy Studies Environmental Education, NGOs and Media Science and Shri Rangaswamy Plantation of 3456 Unstarred 26.04.2012 Technology Dhruvanarayana Permanent Pillars Disaster Management INC Karnataka Health and Sanitation Environmental Science and Shri Kotla Jaya Surya Radiation from Education, NGOs and Andhra 3467 Unstarred 26.04.2012 Technology Prakash Reddy Mobile Towers Media INC Pradesh Health and Sanitation Pollution Survey in the Field Science and Shri Marotrao Sainuji of Forest and Hilly 3484 Unstarred 26.04.2012 Technology Kowase Areas Agriculture INC Maharashtra Forest Conservation Medicinal Plants National Mission for Sustaining Science and Himalayan Eco- Environmental 3556 Unstarred 26.04.2012 Technology Shri Manish Tewari system Conservation INC Punjab Environmental Education, NGOs and Media Science and Shri Sameer Magan Budgetary 3562 Unstarred 26.04.2012 Technology Bhujbal Allocation for Bio- Agriculture NCP Maharashtra safety Research of GMOs Biosafety Environmental Education, NGOs and Media Nano Technology Science and Smt. Deepa for Purification/ -

LIST of FUNCTIONAL GROUPS of MINISTERS (Goms) As on 03.04.2014

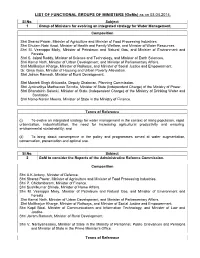

LIST OF FUNCTIONAL GROUPS OF MINISTERS (GoMs) as on 03.04.2014. Sl.No. Subject 1 Group of Ministers for evolving an integrated strategy for Water Management. Composition Shri Sharad Pawar, Minister of Agriculture and Minister of Food Processing Industries. Shri Ghulam Nabi Azad, Minister of Health and Family Welfare, and Minister of Water Resources. Shri M. Veerappa Moily, Minister of Petroleum and Natural Gas, and Minister of Environment and Forests. Shri S. Jaipal Reddy, Minister of Science and Technology, and Minister of Earth Sciences. Shri Kamal Nath, Minister of Urban Development, and Minister of Parliamentary Affairs. Shri Mallikarjun Kharge, Minister of Railways, and Minister of Social Justice and Empowerment. Dr. Girija Vyas, Minister of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation. Shri Jairam Ramesh, Minister of Rural Development. Shri Montek Singh Ahluwalia, Deputy Chairman, Planning Commission. Shri Jyotiraditya Madhavrao Scindia, Minister of State (Independent Charge) of the Ministry of Power. Shri Bharatsinh Solanki, Minister of State (Independent Charge) of the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation. Shri Namo Narain Meena, Minister of State in the Ministry of Finance. Terms of Reference (i) To evolve an integrated strategy for water management in the context of rising population, rapid urbanization, industrialization, the need for increasing agricultural productivity and ensuring environmental sustainability; and (ii) To bring about convergence in the policy and programmes aimed at water augmentation, conservation, preservation and optimal use. Sl.No. Subject 2 GoM to consider the Reports of the Administrative Reforms Commission. Composition Shri A.K.Antony, Minister of Defence. Shri Sharad Pawar, Minister of Agriculture and Minister of Food Processing Industries. -

Page7.Qxd (Page 1)

DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU FRIDAY, APRIL 26, 2019 (PAGE 7) Only BJP did justice with Fire damages standing wheat India needs decisive Ladakh region: Jamyang crop on 250 kanals of land PM like Modi: Kavinder Excelsior Correspondent of Ladakh region. “Under Prime Minister, Narendra Modi led BJP Excelsior Correspondent was also damaged in fire belong- Excelsior Correspondent tion parties `Mahagathbandhan' KARGIL (LADAKH), Apr ing to Sardari Lal, resident of vil- to defeat Modi in the 2019 gen- Government, Ladakh has seen KATHUA/ SAMBA, Apr 25: 25: Only Bharatiya Janata Party lage Changal in Kathua. JAMMU, Apr 25: Prime eral elections. unprecedented development with Fire broke out in wheat fields in a Minister, Narendra Modi is a (BJP) did justice with the Ladakh the liberal fundings from the The farmers asked the district In Jammu and Kashmir, a region by taking cognition of the vast area in Kathua and Samba administration to assess the loss "decisive" leader under whose Central Government. districts today damaging the `Mahamilawat' of NC, PDP and aspirations of nationalist popula- Hitting out at Congress party, and issue ex-gratia relief for the leadership the country has sus- Congress has been made to play tion of the Himalayan region. This standing crops worth several families for their sustenance as tained high average growth Jamyang said Congress lakhs of rupees belonging to vari- with the sentiments of Jammu was stated by Jamyang Tsering Governments always backstabbed except agriculture they have no without stoking inflation. and Ladakh regions just to send Namgyal, BJP's MP candidate for ous farmers of the twin districts.