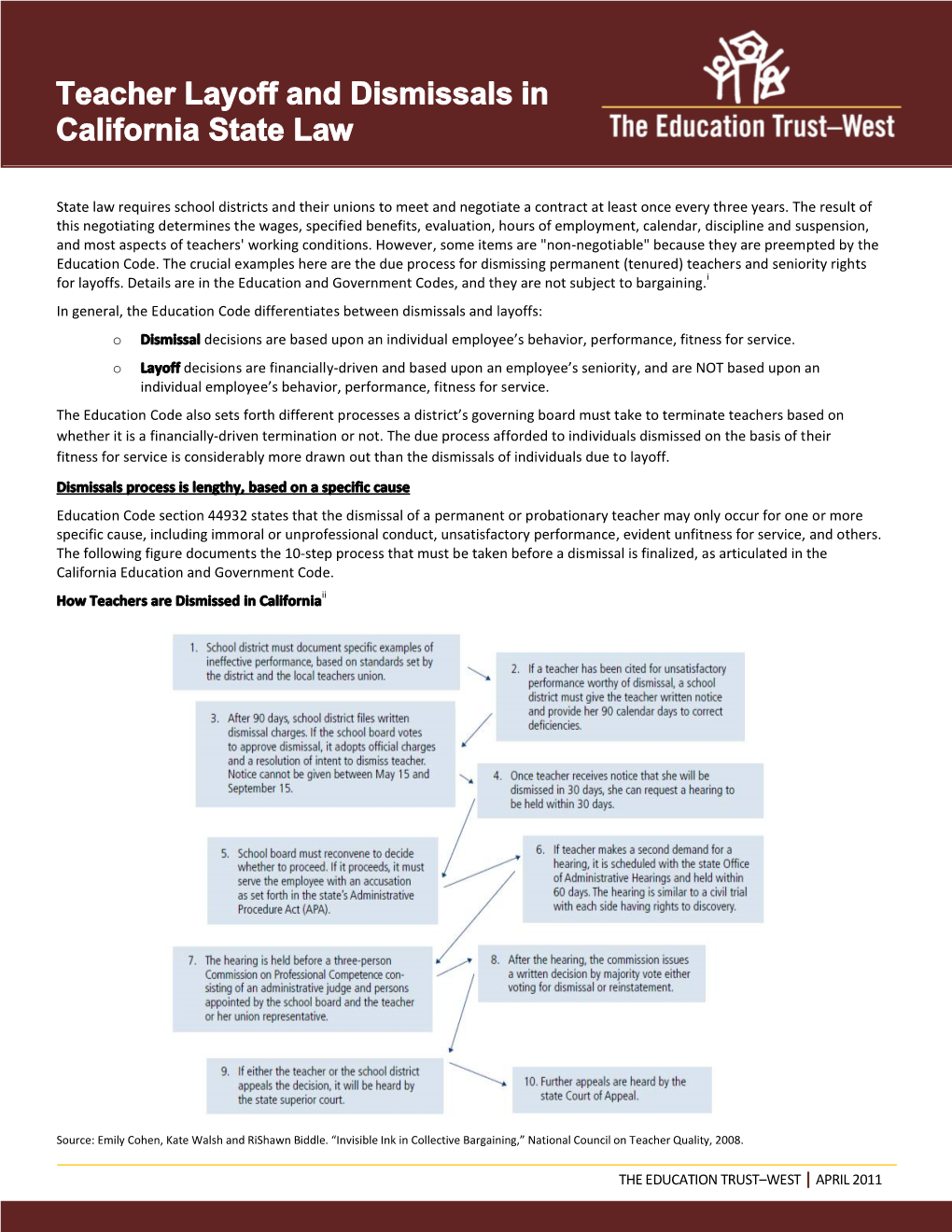

Teacher Layoff and Dismissals in California State Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Background - EMPLOYEE DISMISSAL

Background - EMPLOYEE DISMISSAL The dismissal of an employee is never an easy or pleasant task and is also one that, if not handled properly, can result in future costly and time consuming problems. However if a few simple rules are followed, the potential problems of cost and time may be avoided. Any employee (other than a unionized employee covered by a Collective Agreement)* can be released at any time, with or without just cause, if the relevant rules and regulations of the applicable provincial or territorial Employment Standards Legislation are adhered too. *(A Collective Agreement covering unionized employees will contain provisions concerning discipline, suspension, discharge and an arbitration procedure which must be followed in an employee dismissal process). The applicable Employment Standards Legislation will include a required notice period (a number of weeks based on length of employment) that must be provided to an employee whose employment is to be terminated. The employer has the unilateral right to provide pay in lieu of the notice period which is the usual choice in the case of an employee dismissal. An employer is not required to provide any notice, or pay in lieu of notice, if an employee is dismissed for what is commonly referred to as “Just Cause”. What is “Just Cause”? Jurisprudence, in the case of an employee dismissal, considers it as follows. “If an employee has been guilty of serious misconduct, habitual neglect of duty, incompetence, or conduct incompatible with his duties, or prejudicial to the employer’s business, or if he has been guilty of willful disobedience to the employer’s orders in a matter of substance, the law recognizes the employer’s right summarily to dismiss the delinquent employee”. -

M.D. Handbook and Policies

M.D. Handbook and Policies 1 Please note that information contained herein is subject to change during the course of any academic year. Wayne State University School of Medicine (WSUSOM) reserves the right to make changes including, but not limited to, changes in policies, course offerings, and student requirements. This document should not be construed in any way as forming the basis of a contract. The WSUSOM Medicine M.D. Handbook and Policies is typically updated yearly, although periodic mid-year updates may occur when deemed necessary. Unlike degree requirements, changes in regulations, policies and procedures are immediate and supersede those in any prior Medical Student Handbook. The most current version of the WSUSOM of Medicine M.D. Handbook and Policies can always be found on the School of Medicine website. UPDATED 09.15.2021 UNDERGRADUATE MEDICAL EDUCATION MAJOR COMMITTEES • Admissions Committee • Curriculum Committee • Institutional Effectiveness Committee • Professionalism Committee • Promotions Committee 2 DOCUMENT OUTLINE 1. GENERAL STANDARDS 1.1 NEW INSTITUTIONAL DOMAINS OF COMPETENCY AND COMPETENCIES • Domain 1: Knowledge for Practice (KP) • Domain 2: Patient Care (PC) • Domain 3: Practice-Based Learning and Improvement (PBLI) • Domain 4: Interpersonal and Communication Skills (ICS) • Domain 5: Professionalism (P) • Domain 6: Systems-Based Practice (SBP) • Domain 7: Interprofessional Collaboration (IPC) • Domain 8: Personal and Professional Development (PPD) • Domain 13: Entrustable Professional Activities for Entering -

Unemployment Insurance: Effect of Receipt of Dismissal Payments At

Hastings Law Journal Volume 8 | Issue 2 Article 10 1-1957 Unemployment Insurance: Effect of Receipt of Dismissal Payments at Time of Discharge from Employment Upon Eligibility for State Unemployment Insurance Benefits Robert P. Long Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert P. Long, Unemployment Insurance: Effect of Receipt of Dismissal Payments at Time of Discharge from Employment Upon Eligibility for State Unemployment Insurance Benefits, 8 Hastings L.J. 233 (1957). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol8/iss2/10 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. MYarch, 1957 NOTES March, 1957 NOTES of the motorist to use the highway unobstructed by obstacles. Viewing this situa- tion from a different plane, as if literally turning the highway over on its side, the problem is still the same and the substitution of an aircraft for the automobile does not present a new factor. The duty of each party should remain constant. With the development of extensive modem air travel over heavily populated areas, the duties of the aviators and the landowners should be clearly defined. The aviator aloft in his aircraft is no longer considered an interloper as to the normal social and business activities of those on the ground. He is no longer a trespasser as a matter of law for operating below certain altitudes.19 The duty of the landowner to the aircraft above is not an unbearable burden. -

Preventing Wrongful Dismissal Claims

Preventing Wrongful Dismissal claims Agenda • Employment “At will” • Termination: What is fair and legal • What is “Wrongful Dismissal” • Beware of Constructive Dismissal • Preventing Wrongful Dismissal claims: 1) ALWAYS consult an employment lawyer 2) Include a Termination Clause 3) Follow your own disciplinary policy 4) Use termination as a last resort 5) NEVER terminate “for cause” • Termination as a last resort • What to do if a claim is made Employment “At Will” • Legal environment in Canada for employment contract is one called: “Employment At Will” • In essence, the employment contract is “at the will of the employer” • Employers can terminate employment at any time, without any reason • Employers also have legal obligations to their employees, to prevent abuse of employees: – At the core of these obligations, your legal duty is to treat employees fairly and in good faith 1 Employment “At Will” • Employers have legal obligations to their employees to prevent abuse such as: – Provide a safe work environment – Provide competent servants – Provide proper tools with which to perform their duties – To warn them of inherent dangers in their work process, particularly those that are not open and/or apparent – To make reasonable rules for the safe performance of said work – To provide reasonable notice that the employment will be terminated Termination of Employment • The law requires you to give an employee proper notice that their employment will end at a specific date • The law requires you to pay the employee during this notice period • You are not obligated to have the employee report to work during this notice period, but payments are required • You do not have any obligations to give the employee any reasons 2 Termination of Employment • It is strongly recommended to NEVER give a reason for termination, because: – Not required by law – Reason or reasons can be used against you to allege discrimination – Provide a platform for the employee to debate with you why he/she should not be terminated – The moment of termination is emotionally charged. -

Notice of Dismissal, Layoff Or Termination 1

Employment Standards Notice of Dismissal, Layoff or Termination 1. How are the terms dismissal, layoff, termination, 3. What are the requirements should an employer choose to suspension, and period of employment defined in the New terminate or layoff an employee? Brunswick Employment Standards Act? Where an employee has been employed with an dismissal – the termination of the employment employer for less than six months, the employer is not relationship for cause at the direction of the required to give the employee advance notice of the employer. termination or layoff. layoff – a temporary interruption of the employment Where an employee has been employed with an relationship at the direction of the employer because employer for a period of at least six months but less of lack of work. than five years, the employer must give the employee at least two weeks written notice of the termination or termination – the unilateral severance of the layoff. employment relationship at the direction of the employer. Where an employee has been employed with an employer for a period of five years or more, the suspension – a temporary interruption of the employer must give the employee at least four weeks employment relationship other than a layoff at the written notice of the termination or layoff. direction of the employer. The employer may choose to pay the employee the period of employment – the period of time from the wages the employee would have earned during the last hiring of an employee by an employer to the applicable two or four week notice period instead of termination of his/her employment, and includes any providing a written notice. -

Bullying and Harassment of Doctors in the Workplace Report

Health Policy & Economic Research Unit Bullying and harassment of doctors in the workplace Report May 2006 improving health Health Policy & Economic Research Unit Contents List of tables and figures . 2 Executive summary . 3 Introduction. 5 Defining workplace bullying and harassment . 6 Types of bullying and harassment . 7 Incidence of workplace bullying and harassment . 9 Who are the bullies? . 12 Reporting bullying behaviour . 14 Impacts of workplace bullying and harassment . 16 Identifying good practice. 18 Areas for further attention . 20 Suggested ways forward. 21 Useful contacts . 22 References. 24 Bullying and harassment of doctors in the workplace 1 Health Policy & Economic Research Unit List of tables and figures Table 1 Reported experience of bullying, harassment or abuse by NHS medical and dental staff in the previous 12 months, 2005 Table 2 Respondents who have been a victim of bullying/intimidation or discrimination while at medical school or on placement Table 3 Course of action taken by SAS doctors in response to bullying behaviour experienced at work (n=168) Figure 1 Source of bullying behaviour according to SAS doctors, 2005 Figure 2 Whether NHS trust takes effective action if staff are bullied and harassed according to medical and dental staff, 2005 2 Bullying and harassment of doctors in the workplace Health Policy & Economic Research Unit Executive summary • Bullying and harassment in the workplace is not a new problem and has been recognised in all sectors of the workforce. It has been estimated that workplace bullying affects up to 50 per cent of the UK workforce at some time in their working lives and costs employers 80 million lost working days and up to £2 billion in lost revenue each year. -

In Re African-American Slave Descendants Litig

In the United States Court of Appeals For the Seventh Circuit ____________ Nos. 05-3265, 05-3266, 05-3305 IN RE: AFRICAN-AMERICAN SLAVE DESCENDANTS LITIGATION. APPEALS OF: DEADRIA FARMER-PAELLMANN, et al., and TIMOTHY HURDLE, et al. ____________ Appeals from the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, Eastern District. No. 02 C 7764—Charles R. Norgle, Sr., Judge. ____________ ARGUED SEPTEMBER 27, 2006—DECIDED DECEMBER 13, 2006 ____________ Before EASTERBROOK, Chief Judge, and POSNER and MANION, Circuit Judges. POSNER, Circuit Judge. Nine suits were filed in federal district courts around the country seeking monetary relief under both federal and state law for harms stemming from the enslavement of black people in Amer- ica. A tenth suit, by the Hurdle group of plaintiffs, makes similar claims but was filed in a state court and then removed by the defendants to a federal district court. The Multidistrict Litigation Panel consolidated all the suits in the district court in Chicago for pretrial proceedings. 28 2 Nos. 05-3265, 05-3266, 05-3305 U.S.C. § 1407. Once there, the plaintiffs (all but the Hurdle plaintiffs, about whom more shortly) filed a consoli- dated complaint, and since venue in Chicago was proper and in any event not objected to by the parties (other than the Hurdle group, whose objection we consider later in the opinion), the district court was unquestionably autho- rized, notwithstanding Lexecon Inc. v. Milberg Weiss Bershad Hynes & Lerach, 523 U.S. 26, 28 (1998), to determine the merits of the suit. In re Carbon Dioxide Industry Antitrust Litigation, 229 F.3d 1321, 1325-27 (11th Cir. -

Teachers Have Rights, Too. What Educators Should Know ERIC

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 199 144 SO 013 200 AUTHOR Stelzer, Leigh: Banthin, Joanna TITLE Teachers Have Rights, Too. What Educators ShouldKnow About School Law. INSTITUTICN ERIC Clearinghouse for Social Studies/SocialScience Education, Boulder, Colo.: ERIC Clearinghouseon Educational Management, Eugene, Oreg.: SocialScience Education Consortium, Inc., Boulder, Colo- SPCNS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, D.C.: National Inst. of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. DEPORT NO ISBN-0-86552-075-5: ISBN-0-89994-24:.-0 FOB CATE BO CONTRACT 400-78 -0006: 400-78-0007 NOTE 176p. AVAILABLE FPOM Social Science Education Consortium,855 Broadway, Boulder, CO 80802 (S7.95). EDFS PRICE ME01/PCOB Plus Postage. CESCRIPTCPS Academic Freedom: Discipline: *Educational Legislation: Elementary Secondary Education:Ereedom of Speech: Life Style: Malpractice;Reduction in Force: *School Law: Teacher Dismissal:Tenure IDENTIFIERS *Teacher Fights ABSTRACT This book addresses the law-relatedconcerns of school teachers. Much of the datacn which the book is based was collected during a four year stlzdy, conducted bythe American Bar Association with the support of the Ford Foundation.Court cases are cited. Chapter one examines "Tenure." Sincetenure gives teachers the right to their jobs, tenured teachers cannotbe dismissed without due process cf law or without cause. They are entitled to noticeof charges and a fair hearing, with the opportunityto present a defense. The burden is on school authoritiesto show that there are good and lawful reasons for dismissal. "ReductionIn Force (RIF)" is the topic cf chapter two. Many school districtsare facing declining enrollments and rising costs for diminishedservices. EIF begins with a decision that a school district has too many teachers.Laws vary from state to state. -

Section VII– Personnel Table of Contents

Section VII– Personnel Table of Contents Article I – General Provisions 7-1.1 Equal Employment Opportunity ......................................................................................... 4 7-1.2 Harassment – School Personnel .......................................................................................... 5 7-1.3 Board-Staff Communications ........................................................................................... 11 7-1.4 Personnel Records ............................................................................................................. 11 7-1.5 Personnel – Statement of Ethics ....................................................................................... 13 7-1.6 Official Status as School Division Employee ................................................................... 13 Article II – Hiring, Appointment and Transfer 7-2.1 Posting of Vacancies and Recruitment ............................................................................. 14 7-2.2 Application for Positions .................................................................................................. 14 7-2.3 Hiring: Health Issues......................................................................................................... 14 7-2.4 Hiring: Criminal Background Checks and Fingerprinting ................................................ 16 7-2.5 Hiring: Nepotism and Conflict of Interest Prohibitions .................................................... 19 7-2.6 Hiring: Temporary Personnel, Part-Time and -

Individual Dismissal

Individual Dismissal India VITTE Oualid EL FAGROUCHI François SAID Géraldine PILARD-MURRAY EWL 2018 EWL 2018 – French Report Table of contents I. Introductory statements p. 4 1) The definition of “dismissal” p. 4 2) The grounds of dismissals p. 4 II. Factors for allowing dismissals p. 7 III. Sources of law regarding dismissals p. 7 IV. Criteria for allowing dismissals p. 10 1) The need of a lawful reason for dismissal p. 10 a) Criterion allowing the dismissal p. 10 b) Disciplinary and non-disciplinary reasons p. 10 c) Unlawful reasons p. 12 2) Dismissal, a management tool? P. 13 V. Formal and procedural requirements p. 15 1) The letter of invitation to a preliminary interview p. 15 2) Preliminary interview p. 15 3) The dismissal letter p. 16 4) Notice period p. 17 5) Consequence of a breach of procedure p. 17 VI. The role of the labour authority, workers’ representatives, and/or collective agreements in dismissal p. 18 Page | 2 EWL 2018 – French Report VII. Judicial control of dismissal p. 19 1) Control of the preliminary interview p. 19 2) Control of the letter of dismissal p. 19 3) Control of the real and serious motive p. 20 4) Matter of the control p. 20 5) Admissibility of the remedy p. 21 6) Control exercised on the employee’s evidence p. 21 7) Investigative measures p. 22 VIII. The consequences and effects of a lawful and unlawful p. 23 dismissal 1) The amount of compensation p. 23 2) The enforcement of the sentence p. 24 3) Error of qualification p. -

Good Practice in Whistleblowing Protection Legislation (WPL)

www.transparency.org www.cmi.no Good Practice in Whistleblowing Protection Legislation (WPL) Query: “I am interested in good practices in law and practice for the protection of whistleblowers as provided for in UNCAC Art. 8.4, 32 and 33. Could you give some indications regarding model legislation or aspects to be considered for the development of whistle blower protection legislation? Further, do you know about good practices to implement such legislation especially from developing countries?” Purpose: An increasing number of countries is adopting I am working in Bangladesh on UNCAC Whistleblowing Protection Legislation (WPL), to protect implementation. One national priority is to develop whistleblowers from both the private and public sector from occupational detriment such as dismissal, sound legislation and mechanisms for whistle- suspension, demotion, forced or refused transfers, blower protection. So far, they are non existent ostracism, reprisals, threats, or petty harassment. apart from money laundering offences. Good practice WPL includes adopting comprehensive free standing laws that have a broad scope and Content: coverage, provide adequate alternative channels of reporting both internally and externally, protect as far as Part 1: Best Practice Whistleblowing possible the whistleblower’s confidentiality and provide for legal remedies and compensation. As WPL is still in Protection Legislation its infancy, little is known yet on its impact and the Part 2: Good Practice in Implementing conditions of effective implementation. Whistleblowing -

Constructive Dismissal – a Primer

CONSTRUCTIVE DISMISSAL – A PRIMER By Ernest A. Schirru & Jody Brown of Koskie Minsky LLP Introduction Employment relationships may end in a variety of different ways: (i) the employer terminates the relationship for cause with no notice, (ii) the employer terminates the relationship without cause by giving notice or payment in lieu of notice, (iii) the employee terminates the relationship, (iv) the relationship comes to an end due to frustration, (v) the relationship comes to an end due to job abandonment, (vi) the relationship comes to an following the completion of a fixed term contract, and (vi) constructive dismissal. Constructive dismissal claims are premised on long standing principles of general contract law. Constructive dismissal occurs when the employer commits a “repudiatory” breach of the employment contract which either demonstrates that it no longer intends to observe the terms of the employment agreement or whose consequences deprive the employee of substantially all of the benefits the employee bargained for, thus allowing the employee to terminate the employment contract and recover damages.1 In the modern leading constructive dismissal case of Farber v. Royal Trust Co., the Supreme Court described constructive dismissal as follows: Where an employer decides unilaterally to make substantial changes to the essential terms of an employee’s contract of employment and the employee does not agree to the changes and leaves his or her job, the employee has not resigned, but has been dismissed. Since the employer has not formally dismissed the employee, this is referred to as “constructive dismissal”. By unilaterally seeking to make substantial changes to the essential terms of the employment contract, the employer is ceasing to meet its obligations and is therefore terminating the contract.