Corso Di Laurea (Vecchio Ordinamento, Ante D.M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Grimston Rectors by Stephanie Hall © 2021

Our Grimston Rectors By Stephanie Hall © 2021 Contents Page Our Medieval Rectors ............................................................................................................................. 2 Rev Thomas Hare .................................................................................................................................... 5 Rev Nicholas Carr- died 1530 .................................................................................................................. 6 Rev Richard (or Edward) Rochester died in 1560 ................................................................................... 7 Rev Rochester , 1530 – 1560 ................................................................................................................... 8 Rev William Pordage (Porridge) - died 1585 .......................................................................................... 9 Reverend William Thorowgood , 1544 – 1625 ..................................................................................... 10 Reverend Thomas Thorowgood, 1588 -1669........................................................................................ 12 Rev John Brockett 1613-1664 ............................................................................................................... 14 Reverend Thomas Cremer 1635 - 1694 ................................................................................................ 16 Reverend John Cremer 1663 - 1743 .................................................................................................... -

Norfolk. Bishopric. Sonmdn: Yarii'outh Lynn Tmn'rl'oimfl

11 0RF0LK LISTS W 1 Q THE PRESENT TIME; ‘ . n uu lj, of wuum JRTRAITS BLISHED, vE L l s T 0 F ' V INCIAL HALFPENNIES ' - R N ORFOLK LIS TS FROM THE REFORMATION To THE PRESENT TIME ; COMPRIS ING Ll" OP L ORD LIEUTEN ANT BARONET S , S , HIG HERIFF H S S , E B ER O F P A R L IA EN T M M S M , 0 ! THE COUNTY of N ORFOLK ; BIS HOPS DEA S CHA CELLORS ARCHDEAC S , N , N , ON , PREBE DA I N R ES , MEMBERS F PARLIAME T O N , MAYORS SHERIFFS RECORDERS STEWARDS , , , , 0 ? THE CITY OF N ORWIC H ; MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT AND MAYORS 0 ? THE BOROUGHS OP MOUTH LYN N T T R YAR , , HE FO D, AN D C ASTL E RIS IN G f Persons connected with th e Coun Also a List o ty, of whom ENGRAVED PORTRAITS I HAV E B EEN PUBL SHED, A N D A D B S C R I P 'I‘ I V E L I S T O F TRADES MENS ’ TOKIBNS PROV INCIAL HA LFPENNIES ISS UED I” THE Y COUNT OF NORFOLK . + 9 NORWICH ‘ V ' PRINTED BY HATCHB IT, STE ENSON , AN D MATCHB", HARKBT PLACI. I NDEX . Lord Lieutenants ' High Sherifl s Members f or the County Nonw xcH o o o o o o o 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Prebendaries Members f or th e City Ym ou'rn Mayors LYNN Members of Parliament Mayors Membersof Parliament CASTLERISING Members of Parliament Engraved Portraits ’ Tradesmans Tok ens ProvincialHalf pennles County and B orough Members elected in 1 837 L O RD L I EUT EN A N T S NORFOLK) “ ' L r Ratcli e Ea rl of us e h re d Hen y fl n S s x , e si ed at Attle borou h uc eded to th e Ea r d m1 1 g , s ce l o 542 , ch . -

I 'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': a NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF

'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': A NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF JUSTICES OF THE PEACE IN MID-TUDOR ENGLAND, 1547-1582 _____________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _____________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _____________ By Clarissa Elisabeth Hinojosa May 2014 i 'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': A NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF JUSTICES OF THE PEACE IN MID-TUDOR ENGLAND, 1547-1582 _____________ An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _____________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _____________ By Clarissa Elisabeth Hinojosa May 2014 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is a national study of English justices of the peace (JPs) in the mid- Tudor era. It incorporates comparable data from the reigns of Edward VI, Mary I, and the Elizabeth I. Much of the analysis is quantitative in nature: chapters compare the appointments of justices of the peace during the reigns of Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I, and reveal that purges of the commissions of the peace were far more common than is generally believed. Furthermore, purges appear to have been religiously- based, especially during the reign of Elizabeth I. There is a gap in the quantitative data beginning in 1569, only eleven years into Elizabeth I’s reign, which continues until 1584. In an effort to compensate for the loss of quantitative data, this dissertation analyzes a different primary source, William Lambarde’s guidebook for JPs, Eirenarcha. The fourth chapter makes particular use of Eirenarcha, exploring required duties both in and out of session, what technical and personal qualities were expected of JPs, and how well they lived up to them. -

The Canterbury Association

The Canterbury Association (1848-1852): A Study of Its Members’ Connections By the Reverend Michael Blain Note: This is a revised edition prepared during 2019, of material included in the book published in 2000 by the archives committee of the Anglican diocese of Christchurch to mark the 150th anniversary of the Canterbury settlement. In 1850 the first Canterbury Association ships sailed into the new settlement of Lyttelton, New Zealand. From that fulcrum year I have examined the lives of the eighty-four members of the Canterbury Association. Backwards into their origins, and forwards in their subsequent careers. I looked for connections. The story of the Association’s plans and the settlement of colonial Canterbury has been told often enough. (For instance, see A History of Canterbury volume 1, pp135-233, edited James Hight and CR Straubel.) Names and titles of many of these men still feature in the Canterbury landscape as mountains, lakes, and rivers. But who were the people? What brought these eighty-four together between the initial meeting on 27 March 1848 and the close of their operations in September 1852? What were the connections between them? In November 1847 Edward Gibbon Wakefield had convinced an idealistic young Irishman John Robert Godley that in partnership they could put together the best of all emigration plans. Wakefield’s experience, and Godley’s contacts brought together an association to promote a special colony in New Zealand, an English society free of industrial slums and revolutionary spirit, an ideal English society sustained by an ideal church of England. Each member of these eighty-four members has his biographical entry. -

C78/70-79 C78/70

C78/70-79 C78/70 1. 21 Nov. 14 Eliz William Gratewood of Adderley, Salop esq and Alice Corbett, widow v. John Prestland. Manors of Spurstow, Peckforton and Bunbury, Ches, conveyed to Gratewood, and manors of Malpas and Oldcastle, Ches, conveyed to Reynold Corbett by Sir Roland Hill of London, dec. 2. 22 Nov. 14 Eliz Robert Gardiner and wife Anne, daughter of Christopher Hussey, gent v. Thomas Lovell, gent and wife, Elizabeth Manor and advowson of Winterborne Tomson and manors of Edmondsham, Shapwick, Vinters, Kingston, Stourpaine, Duller, Bowood and Peggs, Dors, and Charlton and Bowden, Som, with appurtenances in Dors and Som, late of Thomas Hussey, dec. 3. 14 Nov. 15 Eliz Nicholas Downes, husbandman v. John Crockett and William Unwyn. Customary holding in Burston, held of the manor of Tunstall, Staffs. Redemption of a mortgage of the same for 200 marks. 4. 27 Oct. 15 Eliz George Alsopp of London, cordwainer v. William Crosse and wife Ellen. Messuages and lands in Ashborne and Yeaveley, Derb late of John Alsopp of Woodhouse, Staffs, dec. Defendant claims he holds the premises by courtesy of England. Case previously heard in the court of the Duchy Chamber. Dismission. 5. 14 June 16 Eliz Humphrey Frye v. John Knight. Customary holding in Froxfield, Hants held of the Bishop of Winchester's manor of East Meon, and a lease of the same. 6. 30 Jan. 16 Eliz Thomas Bordfield and John Trumpe v. Ralph Richards. Estate of Phillipa Ridgeway of Exminster, Devon, widow,who died intestate temp Edward VI. 7. 13 June 17 Eliz John Smith, gent and wife Elizabeth v. -

Negotiating Religious Change Final Version.Pdf

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Le Baigue, Anne Catherine (2019) Negotiating Religious Change: The Later Reformation in East Kent Parishes 1559-1625. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent,. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/76084/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Negotiating Religious Change:the Later Reformation in East Kent Parishes 1559-1625 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Studies University of Kent April 2019 Word Count: 97,200 Anne Catherine Le Baigue Contents Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements...…………………………………………………………….……………. 3 Notes …………………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Abbreviations ……………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Maps ……..……….……………………………………………………………………………….…. 4 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Chapter 1: Introduction to the diocese with a focus on patronage …….. 34 Chapter 2: The city of Canterbury ……………………………………………………… 67 Chapter 3: The influence of the cathedral …………………………………………. -

Church Plate in Kent. Parochial Inventories: Acrise to Canterbury

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 17 1887 ( 241 ) CHURCH PLATE IN KENT. BY CANON SCOTT ROBERTSON. PAET II. PAROCHIAL INVENTORIES. ACEISE. PBOM information furnished by the Eev. Edward Newenham Hoare, Eector of Acrise, I learn that the Communion. Vessels used in St. Martin's Church, at Aerise, are (i.) An Elizabethan Cup (1562) of Silver, with Cover; (ii.) A Silver Paten (1702) ; (iii.) An old Alms- plate of Pewter; (iv.) A modern Magon of Glass; and (v.) a mo- dern Alms-dish of Wood. The CUP is 6 inches high, and 3J inches in diameter at the- mouth. Upon its bell-shaped bowl are engraved two horizontal belts, each formed of sprigs of woodbine running between two fillets which interlace three times, at points equi-distant from each other. The fillets are filled with plain JP"-Kke chasing. The stem has a knop, formed of one large round moulding between two smaller ones. Immediately above and below the stem is a moulding of small con- tiguous lozenges. The foot is simply moulded. Near the mouth of the cup, in the upper belt of engraving, are four SALL-HARKS— (i.) badly impressed; perhaps a star; (ii.) leopard's head crowned; (iii.) lion passant; (iv.) date letter $ for A.D. 1562-8. The COVER to this cup has but one MASK, which appears upon its rim. It seems to be L.O. with a small cross or mullet beneath it. The cup and cover together weigh 9-| ounces avoirdupois. The PATEN, 5£ inches in diameter, is of the purer quality of silver called New Sterling, and stands on a central conical foot. -

Local Government and Society in Early Modern England: Hertfordshire and Essex, C

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Local government and society in early modern England: Hertfordshire and Essex, C. 1590-- 1630 Jeffery R. Hankins Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hankins, Jeffery R., "Local government and society in early modern England: Hertfordshire and Essex, C. 1590-- 1630" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 336. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/336 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND SOCIETY IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND: HERTFORDSHIRE AND ESSEX, C. 1590--1630 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of History By Jeffery R. Hankins B.A., University of Texas at Austin, 1975 M.A., Southwest Texas State University, 1998 December 2003 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor Dr. Victor Stater for his guidance in this dissertation. Dr. Stater has always helped me to keep the larger picture in mind, which is invaluable when conducting a local government study such as this. He has also impressed upon me the importance of bringing out individual stories in history; this has contributed greatly to the interest and relevance of this study. -

Bristol, Africa and the Eighteenth Century Slave Trade to America, Vol 1

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY'S PUBLICATIONS General Editor: PROFESSOR PATRICK MCGRATH, M.A. Assistant General Editor: MISS ELIZABETH RALPH, M.A., F.S.A. VOL. XXXVIII BRISTOL, AFRICA AND THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SLAVE TRADE TO AMERICA VOL. 1 THE YEARS OF EXPANSION 1698--1729 BRISTOL, AFRICA AND THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SLAVE TRADE TO AMERICA VOL. 1 THE YEARS OF EXPANSION 1698-1729 EDITED BY DAVID RICHARDSON Printed for the BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 1986 ISBN 0 901583 00 00 ISSN 0305 8730 © David Richardson Produced for the Society by Alan Sutton Publishing Limited, Gloucester Printed in Great Britain CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements vi Introduction vii Note on transcription xxix List of Abbreviations xxix Text 1 Index 193 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the process of compiling and editing the information on Bristol trading voyages to Africa contained in this volume I have been fortunate to receive assistance and encouragement from a number of groups and individuals. The task of collecting the material was made much easier from the outset by the generous help and advice given to me by the staffs of the Public Record Office, the Bristol Record Office, the Bristol Central Library and the Bristol Society of Mer chant Venturers. I am grateful to the Society of Merchant Venturers for permission to consult its records and to use material from them. My thanks are due also to the British Academy for its generosity in providing me with a grant in order to allow me to complete my research on Bristol voyages to Africa. Finally I am indebted to Miss Mary Williams, the City Archivist in Bristol, and Professor Patrick McGrath, the General Editor of the Bristol Record Society, for their warm response to my initial proposal for this volume and for their guidance and help in bringing it to fruition. -

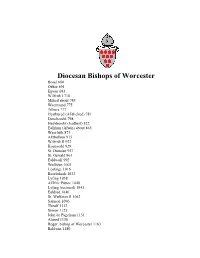

Diocesan Bishops of Worcester

Diocesan Bishops of Worcester Bosel 680 Oftfor 691 Egwin 693 Wilfrith I 718 Milred about 743 Waermund 775 Tilhere 777 Heathured (AEthelred) 781 Denebeorht 798 Heahbeorht (Eadbert) 822 Ealhhun (Alwin) about 845 Waerfrith 873 AEthelhun 915 Wilfrith II 922 Koenwald 929 St. Dunstan 957 St. Oswald 961 Ealdwulf 992 Wulfstan 1003 Leofsige 1016 Beorhtheah 1033 Lyfing 1038 AElfric Puttoc 1040 Lyfing (restored) 1041 Ealdred 1046 St. Wulfstan II 1062 Samson 1096 Theulf 1113 Simon 1125 John de Pageham 1151 Alured 1158 Roger, bishop of Worcester 1163 Baldwin 1180 William de Narhale 1185 Robert Fitz-Ralph 1191 Henry de Soilli 1193 John de Constantiis 1195 Mauger of Worcester 1198 Walter de Grey 1214 Silvester de Evesham 1216 William de Blois 1218 Walter de Cantilupe 1237 Nicholas of Ely 1266 Godfrey de Giffard 1268 William de Gainsborough 1301 Walter Reynolds 1307 Walter de Maydenston 1313 Thomas Cobham 1317 Adam de Orlton 1327 Simon de Montecute 1333 Thomas Hemenhale 1337 Wolstan de Braunsford 1339 John de Thoresby 1349 Reginald Brian 1352 John Barnet 1362 William Wittlesey 1363 William Lynn 1368 Henry Wakefield 1375 Tideman de Winchcomb 1394 Richard Clifford 1401 Thomas Peverell 1407 Philip Morgan 1419 Thomas Poulton 1425 Thomas Bourchier 1434 John Carpenter 1443 John Alcock 1476-1486 Robert Morton 1486-1497 Giovanni De Gigli 1497-1498 Silvestro De Gigli 1498-1521 Geronimo De Ghinucci 1523-1533 Hugh Latimer resigned title 1535-1539 John Bell 1539-1543 Nicholas Heath 1543-1551 John Hooper deprived of title 1552-1554 Nicholas Heath restored to title -

The Antitheatrical Body: Puritans and Performance in Early Modern England, 1577-1620

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE ANTITHEATRICAL BODY: PURITANS AND PERFORMANCE IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND, 1577-1620 Simon W. du Toit, Ph.D., 2008 Directed By: Dr. Franklin J. Hildy, Theatre and Performance Studies The antitheatrical pamphlets published in Shakespeare’s England provide an excellent view of the early modern religious engagement with the stage. However, critics have discussed the antitheatrical pamphlets most often by examining the theology or psychology they seem to represent. This study offers an interdisciplinary approach, as it stands at the shifting boundaries between performance studies, religious studies, and theatre historiography. It offers a close reading of puritan religious experience in the “ethnographic grain,”1 reading the struggle between the puritan and the stage through the lens of a contemporary discourse of embodiment: early modern humoral theory. Puritan practitioners of “spiritual physick” appropriated humoral physiology and integrated it with Calvinist theology to produce the embodied authority of prophetic performative speech. This study’s central claim is 1Robert Darnton, The Great Cat Massacre, and Other Episodes in French Cultural History, (New York: Vintage, 1985). that the struggle between the antitheatrical writers and the stage was a social drama, in which each side fought for social control of the authority of performative speech. I suggest that performance of prophetic speech is the primary signifier of puritan identity in English puritan culture. What distinctively identifies the puritan body is not physiological difference, but cultural practice, visible in the bodily dispositions constructed in puritan culture. The puritan body performs a paradox: it is closed, bridled, contained, and ordered; and it is open, permeable, passionately disclosing, and subject to dangerous motions and disorder. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Post Reformation Catholicism in the Midlands of England Verner, Laura Anne Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 Abstract of a thesis entitled Post-Reformation Catholicism in the Midlands of England Submitted by Laura Anne Verner for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Hong Kong and King’s College London in August 2015 This dissertation examines the Catholic community of the Midlands counties during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603).