Chapter 9 The Economics of Valuation

The value of an asset is the risk adjusted presented value of all future net benefits. Whether or not the market price of an asset will always reflect its value is a source of contention among market participants and academics that study financial markets. Some participants and academics believe that financial markets are efficient in the sense of quickly eliminating mispricing (i.e., price deviating from value).1 We have seen how the adherents of the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) explain why any mispricings do not last long. The EMH provides much of the micro foundations for Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT), while the theory turns around and provides depth to the EMH (e.g., equality of risk adjusted rates of return according to CAPM). Even so, adherents of the EMH and MPT may still be active traders.2 The trading takes place in assets and markets where the assumptions of EMH and MPT are not likely to be fulfilled. Hence, the search for alpha tends to be a search for less efficient markets where more assets tend to be mispriced.

In recent years we have seen a renewed effort to empirically attack the EMH and offer explanations for certain anomalies identified in the markets. We have seen that much of this renewed effort has stemmed from participants and academics that fall under the category of Behavioral Finance. Thus far, we have identified only the investment strategy of technical analysis as being bolstered by Behavioral Finance. However, the new approach may also lend support to those following ‘Fundamental Analysis’ – or, in other words, attempting to determine the intrinsic value of assets. If market prices in financial markets are not governed by the dictums of the EMH, then excess profits (or, excess returns) are possible by identifying intrinsic value. The difficulty that arises for followers of fundamental analysis will be the patience required for market prices to eventually return to intrinsic value. The conundrum is that if one believes that market prices deviate from intrinsic value, then why should one believe also that prices will eventually return to this value? The technical analyst gets around this problem by throwing out intrinsic value all together and focusing on market psychology instead.

The current chapter introduces the basics of valuation – i.e., the soul of fundamental analysis. Although it is quite easy to make a general statement of what determines value (‘intrinsic value’), it is quite another to put this into practice. Even here, we will side-step many of the technical difficulties involved in order to provide an introduction to the approach. The subsequent chapter will present a framework for conducting a competitive analysis of the corporation’s market. It will be recalled from

1 It should be remembered that the terms ‘intrinsic value’, ‘true value’, and ‘fundamental value’ are all used to refer to the value of an asset. The important point being that it – whatever you want to call it – tends to regulate market price, even if the act of regulation takes a considerable amount of time. In this sense, one may also use the terms ‘equilibrium price’, ‘long-run price’, or ‘natural price’ to refer to value. However, the introduction of the word price may lead to some confusion. 2 Recall our previous distinction between ‘traders’ and ‘investors’. A trader has been defined as someone attempting to make abnormal profits in the short run by identify mispricing. An investor, on the other hand, is buying for the long-term and hopes to profit from the growth of the underlying asset. The term trader could be replaced by ‘speculator’ – but the latter terms carries with it negative connotation and requires far more discussion.

1 Chapter 3 that the classical economists assumed that competitive product markets would achieve equilibrium where firms earned equal risk adjusted rates of return. However, there was little discussion of how one should study actual competitive markets. We will focus on a framework developed by Michael Porter as a method of organizing our studies of actual market conditions.

Chapter 11 applies valuation techniques to a variety of situations. Valuation is not limited to stocks (or, equity). In fact, valuation techniques are applied to a variety of financial assets (e.g., bonds, etc.). Moreover, valuation becomes an important resource for attacking several types of questions that arise. Much of Chapter 11 will be devoted to valuing the entire firm. Firm valuation arises, for example, in take-over bids. The point of the chapter will be to introduce the wide variety of ways one may apply the techniques of valuation.

9.1 Cash is King – The Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Method

Considering the generic definition of the value of an asset we can classify the differences in valuation methods differ in terms of (i) what constitutes the net benefit, (ii) how to arrive at estimates of the future net benefits, and (iii) how to adjust for risk. In addition, valuing an asset will require a decision on how to ‘close’ the valuation. Closing the valuation requires a recognition that the further into the future one attempts to forecast, the more difficult – and, most likely, just plain wrong – the estimation will be. The following chapter will help us to come to grips with this difficulty.

Formally, we can demonstrate the differences in valuation methods in the following way.

NB1 NB2 NB3 (9.1) V0 1 2 3 ⋯ (1 k1 ) (1 k2 ) (1 k3 )

Where, V0 is the current value of the asset NBi is the net benefit in period (e.g., year) i ki is the ‘appropriate’ discount rate

Setting aside the question of the ‘appropriate’ discount rate, we must recognize that there are choices to make about what constitutes the net benefit. The Gordon Model was introduced in Chapter 3 as one way to define the net benefit for a stock. There, the net benefit was defined as the dividend paid to the holder of the stock. This was certainly a reasonable definition of net benefit – after all, the ultimate benefit from holding a stock was the dividend payment.3 However, what happens if a corporation chooses not to pay

3 Keep in mind that stock repurchases could be included as net benefits within the Gordon Model. In recent years, stock buybacks have been a favored way to return cash to shareholders by many corporations. An additional benefit occurs when corporations announce a buyback plan at a particular price. Hence, a shareholder has an idea of how far the price of the stock can fall – thus, minimizing the downside risk of owning shares in the corporation.

2 dividends? In fact, corporations that have investment opportunities more profitable than shareholders would do well to retain their earnings.

Given that not all corporations pay dividends, we may want a more general measure of net benefit. It may appear simplistic to replace dividends with earnings, however this gets at something that was actually missing previously. Dividends were direct benefits to the shareholder. However, we know that if a dividend is not paid, the shareholder may still benefit indirectly. The stock represents a claim on the equity of the corporation. Earnings can go one of two places. The earnings can either be paid out as dividends or be kept within the corporation as retained earnings thereby increasing the equity of the corporation. If one could trust the accountant’s measure of earnings, then this could take the place of dividends. We know, however, that the accountant’s measure of earnings – utilizing Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) – is dependent upon several assumptions and a general attempt to match expenses to the revenues they generate. Hence, one may want to adjust earnings to reflect only the cash flow generated and impacting the equity of the firm.

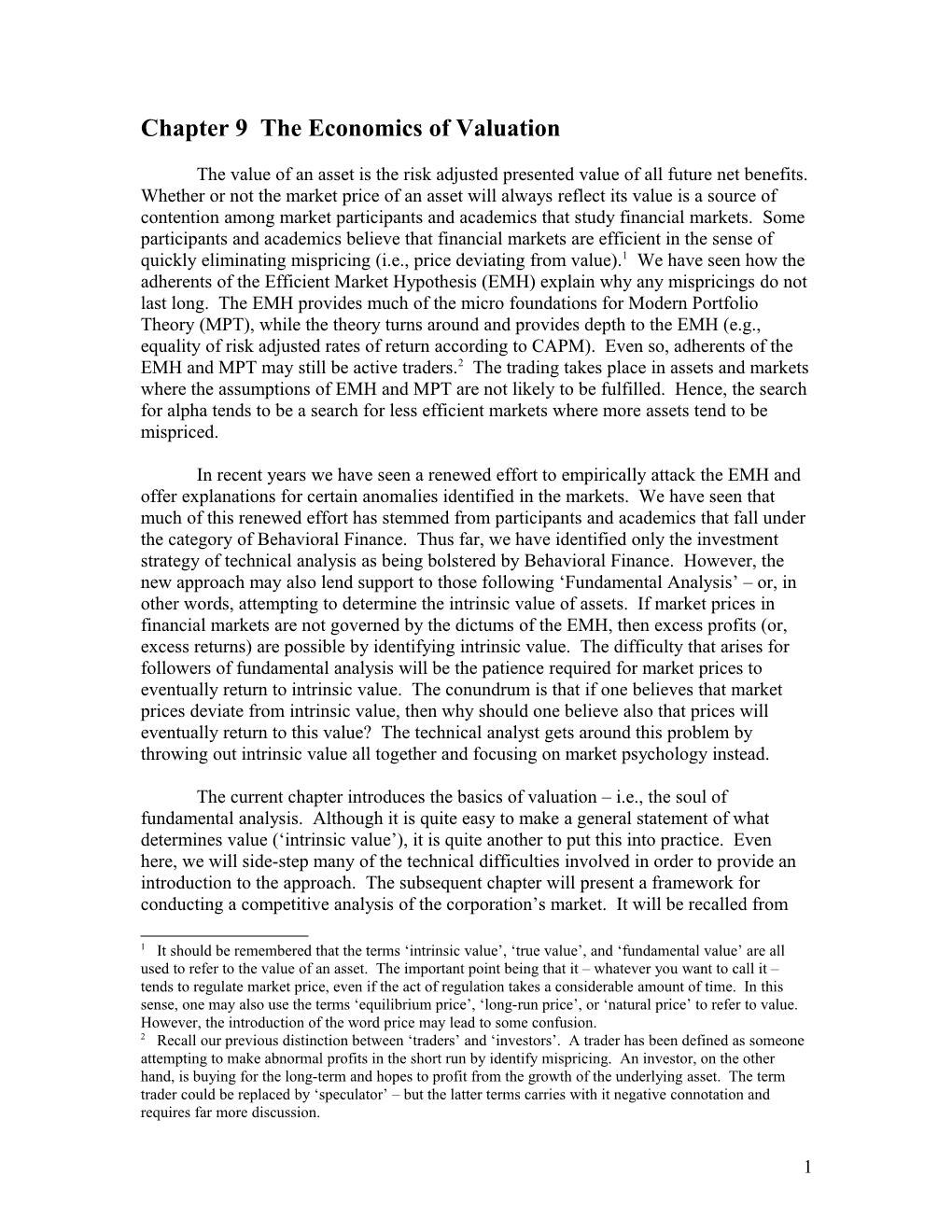

Free Cash Flow to the Firm (FCFF) can be viewed from the angle of its source or its use. FCFF is generated (i.e., source) by the difference between cash flow from operations and cash used to purchase operating assets (i.e., capital expenditures). The FCFF can be used to purchase financial assets, meet financial obligations, or make payments to shareholders (either in the form of dividends or stock buybacks). Figure 9.1 illustrates the generation and use of free cash flow. The cash flow from operations is labeled C, capital expenditures I, flows to and from debt holders or simply the net cash flow to debtholders and issuers F, and flows to and from shareholders or simply net cash flow to shareholders d. We can now state the definition of free cash flow as the following.4

FCFF = C – I = F + d

When the firm generates positive free cash flow, then the cash must end up somewhere. Thus, a positive free cash flow can go towards paying dividends or buying back shares from shareholders (d) or towards paying interest on financial obligations or purchasing financial assets in the form of either bank accounts or bonds (F). A negative free cash flow (C < I) will require the firm to sell some of its financial assets (e.g., decrease a bank account), issue new debt, or issue new equity.

4 The development of free cash flow here follows that of Penman (2007).

3 The Firm Financial Markets

Debtholders C F or Debt issuers Net Net Operating Financial Assets Assets (NOA) (NFA) d Shareholders I

Figure 9.1

Source: financial Statement Analysis and Security Valuation, 3rd edition, Stephen H. Penman, p. 246.

The valuation for a stock requires that only Free Cash Flow to Equity (FCFE) be used. This is the cash flow that could be used to pay dividends. Before deriving the FCFE it is worthwhile to follow the implications of the accounting identities. Suppose we subtract F from both sides.

C – I – F = d

Hence, net payments to shareholders must be the difference between free cash flow and net payments to debtholders and issuers. It is necessary to break into the F a bit in order to understand what is happening. The net cash flow to debtholders and issuers (F) is the difference between the change in net financial assets and net financial income. The net financial assets (NFA) is the difference between financial assets (e.g., bank deposits, bonds held, etc.) and financial obligations (e.g., bank loans, bonds issued, etc.).5 The

5 Financial obligations may include preferred stock as well. Preferred stock is a hybrid security of equity and debt. Preferred stock is equity promising to pay a particular dividend. The promise of the dividend

4 change in net financial assets during a period of time records the net effect of paying down obligations or issuing new obligations. Net financial income (NFI) is the difference between interest earned on financial assets and interest paid on financial obligations.

F = ΔNFA – NFI

Substituting the above definition back into the previous we arrive at a statement for the net payments made to shareholders.

C – I – ΔNFA + NFI = d

We are now ready to state the Free Cash Flow to Equity (FCFE). The change in net financial assets must be broken up into the change in Financial Assets (FA) and the change in Financial Obligations (FO).

ΔNFA = ΔFA – ΔFO

Upon substitution we arrive at the following.

C – I – (ΔFA – ΔFO) + NFI = d

By taking the change in financial assets to the right hand side we get the FCFE.

FCFE = C – I + ΔFO + NFI = d + ΔFA

The far right hand side records the total amount that could be paid to shareholders. If all is paid, then there will be no change in financial assets. If less than what could be paid to shareholders is actually paid, the cash must end up increasing the firm’s financial assets. A typical case might help to clarify the situation. Assume the following:

(1) The firm generates $120 in operating cash flow (2) The firm spends $20 on new operating assets (3) The firm pays down a bank loan by $30 (4) The firms pays $15 in interest (5) The firm receives $5 in interest from a bank account (6) The firm pays out $40 in dividends (7) The firm adds $20 to its bank account

The free cash flow to the firm (FCFF) amounts to $100 ($120 - $20 from 1 and 2). The reduction of the bank loan means that the firm’s financial obligations have been reduced by $30 – a negative change. The net financial income is the difference between the interest received ($5) and interest paid ($15), or -$10. The free cash flow to equity is $60.

makes preferred stock much more like a debt instrument.

5 FCFE = C – I + ΔFO + NFI = $120 - $100 -$30 - $10 = $60

This is the amount that could be paid out to shareholders. In this example only $40 is actually paid out to shareholders, what happens to the remaining $20? The remaining $20 is added to its bank account, thereby increasing its financial assets.

FCFE = d + ΔFA = $40 + $20

The $20 may eventually be used to make capital expenditures, pay off more debt, or anything else the firm chooses. For now, the $20 must be placed somewhere – here, it is in a bank account.6

The Free Cash Flow to Equity (FCFE) constitutes the net benefit in the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) method of valuation. The FCFE must be forecasted and the results discounted (i.e., present value) in order to arrive at the value of equity.

FCFE FCFE FCFE FCFE V 1 2 3 ⋯ i (9.2) 0 1 2 3 i (1 k1 ) (1 k2 ) (1 k3 ) i1 (1 ki )

Presumably, the further into the future the less confidence we will have in our forecasts. In order to avoid attempting to forecast far into the future, we will close the valuation by arriving at a terminal value. For example, suppose we believe forecasting 3 years into the future is best.

FCFE1 FCFE2 FCFE3 T (9.3) V0 1 2 3 3 (1 k1 ) (1 k2 ) (1 k3 ) (1 k3 )

The T stands for the terminal value. A common method of closing DCF valuation is to assume that the terminal value is based on a constant growth rate. For example, we may have chosen to forecast three years out because the firm has exceptional opportunities, which will lead to high growth in FCFE. However, after 3 years elapse, we believe that competition will eliminate the exceptional opportunities leaving FCFE to grow at a constant and sustainable rate. We know from the Gordon Model that an assumption of constant growth reduces to a simple mathematical expression.

FCFE (9.4) T 4 k g

The expression for value under the assumption of a 3 year forecast can now be stated completely.

6 The definition of FCFE given here is actually identical to that given in Darmodaran (p. 89). The apparent difference between the two is reconciled by noting that Net Income in Darmodaran has already been adjusted for the Net Financial Income (NFI) – in the example given, the $10 in net interest payments would have been already subtracted from free cash flow to arrive at net income.

6 FCFE FCFE FCFE 1 FCFE V 1 2 3 4 (9.4) 0 1 2 3 3 (1 k1 ) (1 k2 ) (1 k3 ) (1 k3 ) k g

Or, the DCF can be stated in general.

T FCFE 1 FCFE V i T 1 (9.5) 0 i T i1 (1 ki ) (1 kT ) k g

Example of DCF Valuation. Assume the firm expects that a new product line will generate excess growth in FCFE over the next 4 years. After the fourth year, the firm expects FCFE to grow at a constant 5%. The cost of (equity) capital – or, appropriate discount rate – is thought to be 12%. You have forecasted the FCFE for the next 5 years to be the following.

Year FCFE 1 $100 2 $150 3 $195 4 $225 5 $235

In order to value the equity in the firm, we simply apply equation (9.5)

T FCFE 1 FCFE V i T 1 0 i T i1 (1 ki ) (1 kT ) k g

100 150 195 225 1 235 (1.12)1 (1.12) 2 (1.12)3 (1.12) 4 (1.12)4 .12 .05

89 120 139 143 2134 2,624

In short, we have the equity portion of the firm at $2,624. If, for illustrative purposes, the firm had 100 shares outstanding, then we arrive at a $26.24 value per share.

The example points to a critical feature of a typical DCF valuation. Notice that nearly 80% of the value comes from the terminal value. In practice, the terminal value does in fact tend to explain much of the total valuation (70% is a fairly typical proportion). The assumption about the terminal value (e.g., constant growth rate) becomes extremely important – though often, this gets less attention due to all the hard work going into coming up with accurate forecasts of the FCFE. The DCF method is a rigorous approach to valuation. It has been favored by many for years. However, in practice, the method tends to get watered-down or

7 approximated.7 A complete DCF valuation requires one to not only estimate earnings but go further and estimate cash flows, then cash flows to equity. Estimating FCFE can be quite time consuming and requires a very in-depth knowledge of the inner workings of the firm. In arriving at our definition of FCFE we made a rather large leap at the very beginning when starting with cash flow from operations (C). If one were to begin by estimating earnings (i.e., net income) – which is typical – then several adjustments would need to be made to get to the cash generated in those earnings. For example, sales revenue comes in the form of cash sales and credit sales (appearing as accounts receivable). The credit sales will need to be taken out of the revenue – all non-cash forms of revenue will be subtracted from earnings. Expenses will include non-cash transactions as well. Typically, the two largest categories of non-cash expenses will be depreciation (i.e., expensed tangible assets) and amortization (i.e., expensed intangible assets). Because depreciation and amortization are non-cash expenses, they will need to be added to earnings. In short, if one begins by estimating earnings, then any accruals associated with revenues and expenses will need to be adjusted. The fun does not stop there. Recall, free cash flow deducts capital expenditures as well. Thus, in order to forecast FCFE, one will need to forecast capital expenditures. Often this is done by estimating the capital expenditures required to keep the existing capacity of the firm – unless there is an indication from management of some significant change in the future. Analysts will often produce full valuation models – forecasting each of the three financial statements – for the core stocks they cover, but use truncated versions for related stocks. Part of this is due to time constraints, but the other part is due to the level of knowledge one must have on a corporations to complete a full valuation.8

In practice most DCF models begin with net income (i.e., earnings) and make adjustments for accruals (i.e., non-cash transactions). Darmadaron (xxx – other, big, book) provides a practical and rigorous definition of Free Cash Flow to Equity (FCFE).

7 One may note that Darmodaran’s cash flow definition is likely a bit of a mix. Darmodaran begins his definition of FCFE with Net Income (then subtracts reinvestment and change in debt). By starting with Net Income, Darmodaran has let accrual based accounting seep into the cash flow definition (that is, unless he is making an implicit assumption that accruals have already been taken out – which he may, but he certainly does not draw attention to it). The significant point that Darmodaran seems to be in subtracting the reinvestment needs (i.e., planned capital expenditures), which is fine – kind of. In fact, if Darmodaran has not adjusted Net Income (specifically adding back in depreciation and amortization), then the firm will be penalized twice for making the same capital expenditure (once at the beginning and another time when depreciation gets expensed). 8 [[[NOTE: If Darmodaran will not be used next time, then DCF will need quite a bit of beefing-up. What is needed? 1. a “real” example – GIS might be a good one to use, but should also do one with a high growth corp. (maybe LULU); 2. Cover the various closures in more detail; 3. must cover the various definitions of FCFE in more detail; 4. the “real” example should show how to go from the actual financial statements to FCFE; 5. at some point it should be noted that the change in cash must equal the change in liab + change in equity – change in non-cash assets. 6. how much of this could be done in the previous chapter covering the financial statements and accounting principles? 7. at what point does this chapter get turned into two – one for DCF and one for AB? Would that mean adding even another chapter to just deal with the comparables? The comparables could be pushed into the competition chapter – might make sense anyway, could really draw out how the comparables method is subject to market sentiment (BF, charts, etc.) rather than intrinsic value – you actually get more of ‘relative’ intrinsic value and back to Samuelson’s comment on micro efficient/macro inefficient.]]]

8 FCFE = Net Income – (Capital Expenditures – Depreciation) – (Change in non-cash working capital) + (New Debt Issued – Debt Repayments)

The second line subtracts net capital transactions (notice, depreciation is really an addition to FCFE because it is a non-cash expense). The third line subtracts out the change in non-cash working capital – defined as current assets minus current liabilities – to capture short-term accruals. The last line adds net cash from additional financial obligations. This definition of FCFE does in fact match the previous definition. However, it has the advantage of using terms that appear on actual financial statements. Theoretically, one would need to forecast the income statement and balance sheet for the corporation in order to utilize the definition, as well as the capital expenditures. In practice, it is possible to obtain information on the net debt issued from the corporation’s annual report or conference call, or based on historical debt ratios. Forecasts of the change in non-cash working capital could certainly be made based on historical data. The depreciation during the coming years is obtainable from financial statements (though, this may require reading the footnotes). The capital expenditures would remain to be forecasted, which always presents difficulty for this valuation method. However, the work required to arrive at reasonable forecasts of capital expenditures would certainly be useful in understanding the competitive position and strategy of the corporation.

9.2 Normal Isn’t Good Enough - Abnormal Earnings (AE) Method

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF), with time permitting along with an in-depth knowledge of the corporation, is likely the most rigorous valuation method. Conceptually, there is still a bit of lingering doubt about notion of value creation. The DCF seems to identify value creation with the attainment of cash. Standard accounting practices, though certainly subject to manipulation, identifies value creation with its definition of earnings (or, net income). For valuation purposes, the notion that value is created when earnings occur seems intuitively appealing. The Abnormal Earnings (AE) approach presented here goes a step forward in defining value added as the key net benefit for the valuation model.

We can illustrate the basic insight of the Abnormal Earnings (AE) method with a simple example. Suppose you deposited $100 into a mutual fund account. You required a 5% rate of return on the deposit. At the end of one year, the account had grown to $105. Now, if you could go back in time prior to making the deposit, you may value the account at $100. However, suppose the account had grown to $108 by the end of the year. Again, if you could go back in time prior to making the deposit, what would the value of the account been? Of course, the answer is $102.86 (just finding the present value of $108 a year from now with a 5% discount rate). We can break up the process of determining value in the following way.

Actual Re quired $8 $5 V $100 $100 $100 $2.86 $102.86 (1 .05) (1 .05)

9 When the account earned just the required rate of return (i.e., 5%) then no additional value was created. However, when the account earned an excess (or, abnormal) rate of return, then value was in fact created and added to the original $100. We can think of the value of the equity in the corporation as a rather larger savings account. The book value of the equity (that is, the accountant’s definition of the value of equity as assets minus liabilities) will only increase if the corporation earns more than the required return.

The Book value (B) of a corporation’s shareholder’s equity can be treated much the same as a large savings account. The accountant’s measure of value is similar to the old classical treatment of value discussed in Chapter 3. The accountant measures most assets, liabilities, and shareholders’ equity at historical costs.9 That is, for example, the value of an asset is determined by what it cost at the time of purchase. The cost of a physical asset is at least partially dependent upon the costs of production of the asset (hence, the similarity to the classical approach). As stated in Chapter 3, from the perspective of financial economics, or finance, the value of an asset depends upon its future benefits. We have seen this already with the Discounted Cash Flow where the future benefit was defined in terms of the free cash flow to equity (FCFE). The abnormal earnings (AE) approach takes a similar view, but with a different definition of future benefit.

The abnormal earnings (AE) valuation method finds that the accountant’s definition of earnings is the best representation of value creation. As discussed previously, the accountant’s definition of earnings (or, net income) attempts to match revenue with the expenses associated with generating those revenues (i.e., the so-called matching principle of accrual accounting). However, like the saving account example, the creation of value (i.e., earnings or interest in the above example) does not necessarily translate in value added. Earnings will only lead to value added if those earnings exceed the required return. We can begin to develop the abnormal earnings (AE) by noting the clean surplus identity.

(9.6) B1 B0 E1 D1

Where Bi is the book value of equity in period i Ei is the earnings in period i Di is the dividend payment in period i.

The clean surplus assumes that the book value of equity will not change for any other reason than the difference between earnings and dividends (i.e., the retained earnings within the period). A dirty surplus would allow for changes in the book value of equity for some types of changes in market prices of financial assets, currency translations, and derivatives.10

9 Accounting principles do treat some assets and liabilities at market costs, implying of course that equity may change as well since by definition Equity = Assets – Liabilities.

10 The Abnormal Earnings (AE) approach was a variant of the Dividend Discount Model (DDM) in Chapter 3.11 We can rearrange equation (9.6) to solve for the dividend (D),

(9.7) D1 B0 E1 B1 E1 (B1 B0 ) and replace the dividend with (9.7).

D D E (B B ) E (B B ) V 1 2 ⋯ 1 1 0 2 2 1 ⋯ 0 (1 k)1 (1 k) 2 (1 k)1 (1 k) 2 (9.8) E (B B ) i i i1 i i1 (1 k)

We now use a little algebra trick (note, if you would rather not follow the algebraic manipulations feel free to skip down to the end result of equation 9.15). The following expression is a mere identity (you can check this for yourself by multiplying through be 1+k).12

B kB (9.9) 0 B 0 (1 k)1 0 (1 k)1

We can use this identity by substituting it into the first term on the far right hand side of (9.8).

E (B B ) E B B E B kB (9.10) 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 B 0 (1 k) (1 k) (1 k) (1 k) 0 (1 k)

Recall, the definition of Return on Equity (r) as the earnings (i.e., net income) divided by book value of equity at the beginning of the period. Rearranging the definition of Return on Equity (r) gives us a way to state earnings.

10 For large corporations, the types of changes listed in fact do occur quite often. Multinational corporations always face the issue of translating some of their accounts from one currency to another. Financial corporations nearly always have to adjust some of their financial assets, and therefore equity, for changes in market prices. The abnormal earnings approach to valuation can be done to allow for a dirty surplus. The mechanics merely require us to switch to comprehensive earnings and comprehensive income where these changes are accounted for. Most annual financial statements for large firms show what comprehensive income would be in the detailed shareholders’ equity statement. 11 The Gordon Model presented in Chapter 3 was simply another variation of the Dividend Discount Model. In order to go from the Dividend Discount Model to the Gordon Model one just assumes the dividend will grow at a constant rate forever. 12 It should be noted that we are following the derivation by James English in his excellent little book Applied Equity Analysis (2001). Similar derivations appear in other places – e.g., Penmann (2007) – though with less clarity.

11 (9.11) Ei ri B0

Using the definition of Return on Equity, we can arrange the last expression in (9.10).

E B kB r B kB B (9.12) 1 1 B 0 B 1 0 0 1 (1 k) 0 (1 k) 0 (1 k) (1 k)

We have arrived at an alternative expression for the first term on the far right hand side of (9.8).

E (B B ) E (B B ) V 1 1 0 2 2 1 ⋯ 0 (1 k)1 (1 k) 2 (9.8’) r B kB B E (B B ) B 1 0 0 1 2 2 1 ⋯ 0 (1 k)1 (1 k)1 (1 k) 2

If you have stuck with the derivation this far, then I assume you want to see the rest (it won’t take long now). We now apply the little algebra trick to the second period.

B B kB (9.13) 1 1 1 (1 k) 2 (1 k)1 (1 k) 2

We can substitute (9.13) into the last term expressed in (9.8’) after rearranging.

E (B B ) E B B E B B kB (9.14) 2 2 1 2 2 1 2 2 1 1 (1 k) 2 (1 k) 2 (1 k) 2 (1 k) 2 (1 k)1 (1 k)2

Substituting this back into equation (9.8’) and we find that something drops out.

r B kB B E B B kB V B 1 0 0 1 2 2 1 1 0 0 (1 k)1 (1 k)1 (1 k)2 (1 k)1 (1 k)2 (9.8’’) r B kB r B kB B B 1 0 0 2 1 1 2 ⋯ 0 (1 k)1 (1 k) 2 (1 k)3

Hopefully you see what will happen if we simply repeat this procedure for the third time period, then the fourth, the fifth, etc. The last expression of (9.8’’) keeps dropping out. Upon doing this for the infinite series, we finally arrive at our goal.

r B kB r B kB r B kB V B 1 0 0 2 1 1 ⋯ B i i1 i1 (9.15) 0 0 1 2 0 i (1 k) (1 k) i1 (1 k)

12 This is the Abnormal Earnings (AE) valuation model – we’ll start a new paragraph to discuss it.

The Abnormal Earnings (AE) model of (9.15) looks a bit like the expression we stated for our saving account at the beginning of this section. The value of the asset (e.g., stock) is equal to the book value of equity at the present time period plus the present value of any excess earnings. For any time period, we can state actual and required earnings as the following.

Actual Earnings = ri Bi1

Required Earning = kBi1

Thus, the difference between actual and required is the excess – or, in this case, abnormal – earnings. Of course, we can factor out the book value of equity at the beginning of each period to restate the model.

(r k)B V B i i1 (9.15’) 0 0 i i1 (1 k)

This expression shows us that in order for value to be added to equity, the firm must earn abnormal earnings. It is not enough, in other words, just to create value (or, have positive earnings) the firm must add value by achieving a return on equity exceeding the cost of capital.

The abnormal earnings valuation model has a certain intuitive appeal. Value is enhanced by growth and reinvestment (i.e., an increase in the book value, Bi-1), but only if excess returns (i.e, ROE>k) are being earned. In addition, the intuition of the AE model creates a conceptual bridge between the old classical backward looking view of value and the financial forwarding looking view from Chapter 3. Recall, the classical view was that value was determined by costs of production (or, in the extreme form, by the labor time required in production). The AE model recognizes that part of value is determined by the past. The current book value of equity depends upon costs and past decisions.13 However, the historical costs are only part of the story. Value should also depend upon what future benefits the asset will generate (i.e., forward looking valuation). Here again the classical view had something to offer. If market prices rose, for example, above the intrinsic value, then firms in that market would earn abnormal (or, excess) returns. Eventually, new competitors would enter the market, increasing supply and driving down the market price until the abnormal returns were eliminated. The AE model simply takes the classical view of the competitive process in product markets and draws out the implications for the value of the assets (thus, equity) operating in those markets. To illustrate, suppose two firms had identical balance sheets but one had exclusive rights to

13 Recall, equity is simply net assets (assets minus liabilities). Accounting principles require most assets and liabilities to be recorded at historical costs. Thus, the book value of equity ends up, for the most part, being a record of the historical costs of net assets.

13 produce a particular product, while the other operated in a fiercely competitive market. The classical economists would certainly see that the firm with exclusive rights would be able to earn abnormal returns, while the other firm would earn only the competitive rate of return (e.g., cost of capital). However, they did not seem to take the next step in seeing that this would mean the value of the assets and equity of the firm with exclusive rights would be greater than the other firm. The AE model rectifies this oversight of the classical economists.14

An additional appeal of the AE valuation model is in its application. The model utilizes financial statements prepared under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).15 Adjustments to accrual accounting are not required with this approach. On the other hand, this reminds us that the AE model is simply a rearrangement of the Dividend Discount Model (DDM). The rearrangement provides the intuition behind the DDM. In practice, both models require the same forecasting for a complete valuation. The additional intuition is most helpful when closing the model. Three cases can be used to illustrate bringing closure to the model.

Case 1. Competitive Equilibrium.

Assume that due to market conditions, the analyst believes the firm will achieve abnormal returns for the next two years after which it will just earn the cost of (equity) capital on any investments. The analyst will need to forecast earnings and the payout ratio (i.e., fraction of earnings paid out as dividends – the remaining will be retained within the firm and added to equity for next period) for two years only under the AE model.

AE AE V B 1 2 0 (1 k) (1 k)2

The assumption of reaching a competitive equilibrium in the product market implies that the return on equity (r) equals the cost of capital (k) and no abnormal earnings, thus the valuation stops.

14 We should not be too hard on the old classical economists. It has been accepted that one can define the term value as one likes. If one would like to define the term value as the number of labor hours required to produce a commodity, then so be it. The point is to determine whether the particular definition helps in economic analysis. For some types of analysis a cost of production definition of value may help very much. We are suggesting here that it only partially helps when the analysis concerns assets – both real (physical) and financial. In short, it is not mere semantics that are at stake here, but rather what definition of value helps shed light on understanding asset markets. 15 There are, however, ways in which a rearrangement of the financial statements could lead to better valuations. Analysts using AE may in fact reformulate all three of the main financial statements by grouping accounts in terms of net operating assets and net financial assets. This type of grouping can, and probably should, be used with all valuations models. Accountants have tended to group accounts according to time (e.g., current assets and long-term assets). This particular grouping may help those (e.g., a loan officer at a bank) most interested in understanding the credit worthiness of the firm and/or potential for bankruptcy. For valuation purposes, it is often more useful to understand the division between operating and financial activities. The cash flow statement comes close to this sort of group, but falls short with its definition of investing activities.

14 Case 2. Steady-State Abnormal Earnings

Assume the analyst believes that the firm’s position is quite strong even after the two years. The analyst may forecast out two years, then choose to capitalize a constant amount of abnormal earnings.

AE1 AE2 1 AE3 V B0 (1 k) (1 k)2 (1 k)2 k

This would be a case in which the firm has some permanent competitive advantage in its market. The competitive advantage may arise due to a patent, first-mover, or anything else. The discussion of competitive analysis in the next chapter will take up these issues.

Case 3. Abnormal Earnings Growth

The analyst may have reason to believe that after an extraordinary two year period, the competitive position will only increase for the firm. For example, abnormal earnings are projected to grow at a constant rate (g).

AE AE 1 AE V B 1 2 3 0 2 2 (1 k) (1 k) (1 k) k g

Keep in mind that abnormal earnings may continue to grow either because the return on capital increases or growth in book value (as long as r exceeds g).

A numerical example may help to solidify the ideas. Suppose you are given the following data and forecasts for a particular corporation.

Current Book Value of Equity = $1,000,0000,0000 Shares Outstanding = 10,000,000 Earnings Forecast for Year 1 = $250,000,000 Earnings Forecast for Year 2 = $200,000,000 Payout Ratio = 40% Cost of Capital = 10%

We may use the numbers as given or translate them into per share terms. In per share terms we have the following.

Book Value per share = $100 Earnings per share Year 1 = $25 Earnings per share Year 2 = $20

Thus, we are forecasting a 25% return on equity for the first year. What about the second year? It is not 20%! Given an assumed 40% payout ratio, we are assuming that 60% of

15 earnings (or, $15) will be retained within the corporation and added to the book value of equity. Thus, in year two, the book value per share will be $115 for a return on equity of 17.4%. Now, we can take the three cases in turn, making additional assumptions where necessary.

Case 1. Competitive Equilibrium

(.25 .10)100 (.174 .10)115 V 100 (1.10) (1.10) 2

100 13.63 7.03 $120.67

Case 2. Abnormal Earnings are a constant $4 per share.

15 8.51 1 4 V 100 (1.10) (1.10)2 (1.10)2 .10

100 13.63 7.03 33.06 $153.73

Case 3. Abnormal Earnings will grow at a constant rate of 3% after two years.

15 8.51 1 4 V 100 (1.10) (1.10)2 (1.10) 2 .10 .03

100 13.63 7.03 47.23 $167.89

The value of the stock is influenced by the assumptions made to close the model. However, compared with the DCF method, the AE closure assumptions carry significantly less weight for determination of value. The simple reason is that much of the value is already contained in the beginning book value.16

9.3 Down and Dirty Valuation – The Comparables Method

16 {{{Note: Kind of an abrupt ending to the section. Possible additions: 1. recap what would need to be forecasted. 2. show how to use the ratios to forecast. 3. big question is whether or not to show an example or three using actual corp data. No – need the competitive analysis stuff first in order to do forecasting; Yes – go back in time and use actual data, thus get a valuation from a previous year. 4. do a comparison with DCF/FCFE? Possible. Benefit would be to make clear that DCF/FCFE is in fact the best method. The previous section does not bring this out enough – saying it is the most rigorous doesn’t do it justice. The problem is once you say it’s the best, then why bother learning AE? Also, the way things stand it sounds as if these two are competing – they are, but not the way it sounds. Could show, by example, that the two come to the same valuation if applied consistently --- how messy would that get, and how far off would that take the discussion? The problem is that leaving things as is makes DCF come across as bs and AE is so much better. This is certainly the wrong impression to convey. What about doing an excess returns cash flow model? Could be done fairly quickly – but, so what? If you’re going to do excess returns then AE is simpler and more efficient.???}}}

16 The previous valuation methods avoid using market prices.17 The cost of these valuation methods is the time, information, and patience required. The use of comparables is (very) often used as an alternative method to a complete valuation. This method comes in a variety of forms. For example, Jim Cramer of CNBC’s Mad Money often employs a quick and dirty comparable method whereby value (or, sometimes, a price target) is found in the following way.

P V Em E E

Knowledge of the current, or expected, earnings is combined with some measure of what the market should be willing to pay for those earnings. If one believes, for example, that the corporations is average or above average in the sector or the market as a whole, then one could safely use the average price-earnings ratio in the sector or market to price the earnings. Several techniques have been introduced in order to make this method more rigorous. However, the general idea of this method can be seen quite clearly in Cramer’s use. The weakness of this method, always to be kept in mind, is that value is influenced by current market sentiment. We do not, therefore, arrive at a value of the asset (e.g., corporation) independent of current market prices.

The Gordon Model provides the most straightforward way to derive the various ratios typically employed in the comparables method.18 We will use only two of the possible ratios to illustrate the method, others can be derived similarly. Recall the Gordon Model is a special case of the Dividend Discount Model, whereby dividends are assumed to grow at a constant rate.

D (9.16) P 1 0 k g

Value (V) has been replaced with price (P) for ease of exposition only. The price- earnings ratio is found by simply noting that dividends are paid out of earnings and assuming a constant payout ratio (b).

D1 bE1 P0 b (9.17) P0 k g k g E1 k g

17 We will see that market prices may in fact seep into the valuation. We have avoided any attempts to identify where the actual number to be used for the cost of capital actually comes from. The following chapter takes up this question. One method of identifying the cost of (equity) capital to be used in the valuation models may in fact be influenced by market prices. 18 The price-book ratio can easily be derived from the AE model – simply divide thru by the book value. However, the important drivers for the ratio will be the same as in the Gordon Model. The price-earnings ratio can, with a certain amount of difficulty, be derived from AE as well. There is actually some benefit from deriving price-earnings from the model. In addition to the usual drivers, the AE model demonstrates that price-earnings depend significantly on the growth of abnormal earnings. This may in fact help to explain some of the odd empirical results obtained in using price-earnings.

17 It is possible to break the price-earnings ratio down further, but (9.17) will be far enough for now. We see that the drivers of the price-earnings ratio are the payout ratio (b), growth of dividends and earnings (b), and the cost of (equity) capital (k). The price-book ratio is derived by noting that earnings can be stated as the product of book value (B) and return on equity (r).

D1 bE1 b * rB0 P0 b * r (9.18) P0 k g k g k g B0 k g

The price-book ratio is driven by the same factors as the price-earnings ratio with the addition of the return on equity (r). Again, the drivers can be broken down further into various ratios.19

Intuitively, we can quickly compare a corporation’s ratio (either P/E or P/B) and drivers with others in the same sector or with corporations with similar attributes (e.g., risk factors, debt-levels, balance sheets, stage, etc.). A corporate with lower than average price-book but higher than average return on equity (other drivers being relatively similar) compared with others in its sector could be considered undervalued. A similar process could be conducted for price-earnings ratios. More rigorously, we could run a regression on the ratio with various drivers as independent variables. For example, General Mills operates within Processed & Prepackaged goods sector of the Consumer Goods industry. In November of 2007, General Mills traded at a price-book ratio of 4.16 while earning a return on equity of 23.82%. Choosing 15 related corporations within the sector and running a regression on price-book with only return on equity as the independent variable, we arrive at the following regression.

P 2.16 13.55* ROE B

General Mills’ return on equity can be put into the regression to arrive at a predicted price-book ratio of 5.39. Thus, General Mills is said to be undervalued because it is currently trading at a lower price-book than justified. It is certainly possible to extend this method to include more than one independent variable (e.g., growth, cost of capital, payout ratio). Though, the basic procedure would remain the same. A similar procedure could be conducted for the price-earnings ratio.

The method of comparables continues to be popular in practice. Partly, this is due to the ease of obtaining data and running regressions. Another reason for its popularity is that market sentiment is included in the valuation. The other valuation methods attempt to bypass any market prices and therefore market sentiment. For long term investors, or for many other purposes (e.g., banking), this is most likely preferable. However, if one is valuing for the short-term, then inclusion of current market conditions may in fact be superior (again, in certain type of banking activities – especially investment banking for 19 It is often useful to break-down the return on equity into at least the product of the net profit margin, asset turnover, and equity multiplier – each which could be broken down even further.

18 initial public offerings – the current state of the market should be included). A bull or bear market can last for several years (e.g., the last great bull market in the U.S. was from 1982-1999, the current one is in its fifth year) and not including the state of the market may mislead the analysis. Regardless, it must be recognized that the inclusion of market sentiment in the method of comparables is a departure from traditional valuation models.

9.4 Conclusion

{{{need to write. The comparables section was kept short because Darmadaron covers the same thing in greater detail.}}}

19