Exploring the Politics of Widowhood in Vrindavan: an Analysis of Life Narratives of Vrindavan Widows

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Introduction: Siting and Experiencing Divinity in Bengal

chapter 1 Introduction : Siting and Experiencing Divinity in Bengal-Vaishnavism background The anthropology of Hinduism has amply established that Hindus have a strong involvement with sacred geography. The Hindu sacred topography is dotted with innumerable pilgrimage places, and popu- lar Hinduism is abundant with spatial imaginings. Thus, Shiva and his partner, the mother goddess, live in the Himalayas; goddesses descend to earth as beautiful rivers; the goddess Kali’s body parts are imagined to have fallen in various sites of Hindu geography, sanctifying them as sacred centers; and yogis meditate in forests. Bengal similarly has a thriving culture of exalting sacred centers and pilgrimage places, one of the most important being the Navadvip-Mayapur sacred complex, Bengal’s greatest site of guru-centered Vaishnavite pilgrimage and devo- tional life. While one would ordinarily associate Hindu pilgrimage cen- ters with a single place, for instance, Ayodhya, Vrindavan, or Banaras, and while the anthropology of South Asian pilgrimage has largely been single-place-centered, Navadvip and Mayapur, situated on opposite banks of the river Ganga in the Nadia District of West Bengal, are both famous as the birthplace(s) of the medieval saint, Chaitanya (1486– 1533), who popularized Vaishnavism on the greatest scale in eastern India, and are thus of massive simultaneous importance to pilgrims in contemporary Bengal. For devotees, the medieval town of Navadvip represents a Vaishnava place of antique pilgrimage crammed with cen- turies-old temples and ashrams, and Mayapur, a small village rapidly 1 2 | Chapter 1 developed since the nineteenth century, contrarily represents the glossy headquarters site of ISKCON (the International Society for Krishna Consciousness), India’s most famous globalized, high-profile, modern- ized guru movement. -

Ayodhya Case Supreme Court Verdict

Ayodhya Case Supreme Court Verdict Alimental Charley antagonising rearward. Conscientious Andrus scribbled his trifocal come-backs Mondays. Comedic or deific, Heath never rules any arracks! The ramayana epic were all manner, the important features specific domain iframes to monitor the realization of the request timeout or basic functions of supreme court ruling remain to worship in decision Mars rover ready for landing tomorrow: Know where to watch Pers. Xilinx deal shows AMD is a force in chip industry once more. He also dabbles in writing on current events and issues. Ramayan had given detailed information on how the raging sea was bridged for a huge army to cross into Lanka to free Sita. Various attempts were made at mediation, including while the Supreme Court was hearing the appeal, but none managed to bring all parties on board. Ram outside the Supreme Court. Woman and her kids drink urine. And that was overall the Muslim reaction to the Supreme Court verdict. Two FIRs filed in the case. Pilgrimage was tolerated, but the tax on pilgrims ensured that the temples did not receive much income. In either view of the matter, environment law cannot countenance the notion of an ex post facto clearance. While living in Paris, Maria developed a serious obsession with café culture, and went on to review coffee shops as an intern for Time Out. Do not have pension checks direct deposited into a bank account, if possible. Vauxhall image blurred in the background. The exercise of upgradation of NRC is not intended to be one of identification and determination of who are original inhabitants of the State of Assam. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

VRINDAVAN ECO-CITY in MAKING: Working Together for Sustainable Development

Dr. S. K. Kulshrestha Vrindavan Eco-city in Making 43rd ISOCARP Congress 2007 VRINDAVAN ECO-CITY IN MAKING: Working Together for Sustainable Development INTRODUCTION As a part of the Tenth Five Year Plan, the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) initiated the Eco-city Project, in 2002, with grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Environment and Forest (MoEF), Government of India. The German Technical Cooperation (GTZ), under its Indo- German Programme on Advisory Services for Environmental Management (ASEM), extended the technical support to the project. It is a demonstration project and in its first phase covers the following six selected cities in India: 1. Kottayam, Kerala State, a tourist centre; 2. Puri, Orissa State, a town of cultural significance; 3. Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu State, a pilgrimage and tourist centre; 4. Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh State, a pilgrimage centre; 5. Ujjain, Madhya Pradesh State, a heritage and tourist place; and 6. Vrindavan, Uttar Pradesh State, a heritage and tourist place. Under the project, funds are provided to the municipalities by CPCB for the identified and approved project, on 50:50 cost-sharing basis up to a maximum of Rs. 25 million (Euro 0.5 million) per town, wherein 50 per cent of the total budget should come from the municipalities either from their own funds or through financial institutions or any other source including NGOs and CBOs. The total fund for the first phase, including the share of municipalities is Rs.50 million (Euro 1 million at a conversion rate of Rs.50 per Euro, the same rate will be used throughout this paper). -

The Glories of Vrindavan Dhama the Difference Between Vrindavan Glories of Vrindavana Dhama and the Ordinary World Srila Rupa Goswami His Divine Grace A.C

Çré Ramä Ekädaçé Issue no:98 4th November 2018 THE GLORIES OF VRINDAVAN DHAMA THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN VRINDAVAN GLORIES OF VRINDAVANA DHAMA AND THE ORDINARY WORLD Srila Rupa Goswami His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada VRINDAVAN-DHAMA IS IN THIS WORLD THE STATUS OF THE EARTH IS HIGHER BUT UNTOUCHED BY MATTER. THAN THAT OF THE HEAVENLY PLANETS Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati Thakura Srila Sanatana Goswami SRI BHAKTIVINODA THAKURA VISIT TO BRAJAMANDALA Autobiography of Çré Bhaktivinoda Issue no 98, Page — 2 nityaà bhägavata-sevayä THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN VRINDAVAN AND live there. The sädhus keep cows and THE ORDINARY WORLD provide milk to the tigers, saying, "Come His Divine Grace here and take a little milk." Thus envy A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada and malice are unknown in Vrindavan. That is the difference between Vrindavan and the ordinary world. We are horrified The word vana means "forest" or to hear the word vana, but in the forest “jungle”. Generally, we are afraid of of Vrindavan there is no such horror. the jungle and do not wish to go there, Everyone there is happy in pleasing but in Vrindavan the jungle animals are Krishna. Kåñëotkértana-gäna-nartana- as good as demigods, for they have no parau. Whether a Goswami or a tiger envy. Even in this material world, in the or other ferocious animal, everyone's jungle the animals live together, and there ambition is the same—to please Krishna. are no attacks when they go to drink Even the tigers are also devotees. This is water. Envy develops because of sense the special quality of Vrindavan. -

The Land of Lord Krishna

Tour Code : AKSR0381 Tour Type : Spiritual Tours (domestic) 1800 233 9008 THE LAND OF LORD www.akshartours.com KRISHNA 5 Nights / 6 Days PACKAGE OVERVIEW 1Country 1Cities 6Days Accomodation Meal 3 Nights Hotel Accommodation at mathura 05 Breakfast 2 Nights Hotel Accommodation at Delhi Visa & Taxes Highlights 5 % Gst Extra Accommodation on double sharing Breakfast and dinner at hotel Transfer and sightseeing by pvt vehicle as per program Applicable hotel taxes SIGHTSEEINGS OVERVIEW Delhi :- Laxmi Narayan Temple, Hanuman Mandir, Mathura :- birth place of Lord Krishna Gokul :- Gokul Nath Ji Temple, Agra :- Taj Mahal SIGHTSEEINGS Laxmi Narayan Temple Delhi The Laxminarayan Temple, also known as the Birla Mandir is a Hindu temple up to large extent dedicated to Laxminarayan in Delhi, India. ... The temple is spread over 7.5 acres, adorned with many shrines, fountains, and a large garden with Hindu and Nationalistic sculptures, and also houses Geeta Bhawan for discourses. Hanuman Mandir Delhi Hanuman Temple in Connaught Place, New Delhi, is an ancient Hindu temple and is claimed to be one of the five temples of Mahabharata days in Delhi. ... The idol in the temple, devotionally worshipped as "Sri Hanuman Ji Maharaj" (Great Lord Hanuman), is that of Bala Hanuman namely, Birth place of Lord Krishna Mathura In Hinduism, Mathura is believed to be the birthplace of Krishna, which is located at the Krishna Janmasthan Temple Complex.[5] It is one of the Sapta Puri, the seven cities considered holy by Hindus. The Kesava Deo Temple was built in ancient times on the site of Krishna's birthplace (an underground prison). -

Name of the Candidate: Abhilasha Name of the Supervisor: Prof. Dr. U. K. Popli Name of the Department: Dept. of Social Work Titl

Name of the candidate: Abhilasha Name of the supervisor: Prof. Dr. U. K. Popli Name of the Department: Dept. of Social Work Title of thesis: A Study on Socio-Economic status of elderly widows in pilgrimage cities of Vrindavan, Varansi and Haridwar ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- The present research has been taken up to understand the overview of the life and socio - economic status of elderly widows in our society and look at the problem and issues of elderly widows especially those living in the pilgrimage cities of Vrindavan, Varanasi and Haridwar ashrams. Widows in India suffer from different forms of violence i.e. social isolation, psychological abuse or emotional distress and physical violence or property related violence. The life of a widow is one of dependency on the society. Her position sometimes worsens both socially and economically and she is left alone with her dependent wards. Our society fails to ensure proper rights to its women population, let alone that of the widows. Though there are a few studies on the conditions of elderly widows and widowhood, most of these studies have examined only the emotional adaptations to bereavement. None of the studies were able to look objectively into the existing lifestyle, socio-economic conditions, and issues of elderly widows particularly with reference to the pilgrimage cities of Vrindavan, Varanasi and Haridwar. While doing literature review, the researcher did not come across scientific research available on elderly widows living in the ashrams of Vrindavan, Varanasi and Haridwar in particular. Thus, the present research has been taken up to understand the overview of the life and socio - economic status of elderly widows in our society and look at the problem and issues of elderly widows especially those living in the pilgrimage cities of Vrindavan, Varanasi and Haridwar ashrams.In the present study mixed method has been used for data collection. -

Vrindaban Days

Vrindaban Days Memories of an Indian Holy Town By Hayagriva Swami Table of Contents: Acknowledgements! 4 CHAPTER 1. Indraprastha! 5 CHAPTER 2. Road to Mathura! 10 CHAPTER 3. A Brief History! 16 CHAPTER 4. Road to Vrindaban! 22 CHAPTER 5. Srila Prabhupada at Radha Damodar! 27 CHAPTER 6. Darshan! 38 CHAPTER 7. On the Rooftop! 42 CHAPTER 8. Vrindaban Morn! 46 CHAPTER 9. Madana Mohana and Govindaji! 53 CHAPTER 10. Radha Damodar Pastimes! 62 CHAPTER 11. Raman Reti! 71 CHAPTER 12. The Kesi Ghat Palace! 78 CHAPTER 13. The Rasa-Lila Grounds! 84 CHAPTER 14. The Dance! 90 CHAPTER 15. The Parikrama! 95 CHAPTER 16. Touring Vrindaban’s Temples! 102 CHAPTER 17. A Pilgrimage of Braja Mandala! 111 CHAPTER 18. Radha Kund! 125 CHAPTER 19. Mathura Pilgrimage! 131 CHAPTER 20. Govardhan Puja! 140 CHAPTER 21. The Silver Swing! 146 CHAPTER 22. The Siege! 153 CHAPTER 23. Reconciliation! 157 CHAPTER 24. Last Days! 164 CHAPTER 25. Departure! 169 More Free Downloads at: www.krishnapath.org This transcendental land of Vrindaban is populated by goddesses of fortune, who manifest as milkmaids and love Krishna above everything. The trees here fulfill all desires, and the waters of immortality flow through land made of philosopher’s stone. Here, all speech is song, all walking is dancing and the flute is the Lord’s constant companion. Cows flood the land with abundant milk, and everything is self-luminous, like the sun. Since every moment in Vrindaban is spent in loving service to Krishna, there is no past, present, or future. —Brahma Samhita Acknowledgements Thanks go to Dr. -

P Age | 1 Mathura Vrindavan Yaatraa

P a g e | 1 Mathura Vrindavan Yaatraa Mathura Vrindavan Yaatra As you all knows that, Mathura Vrindavan is world famous Hindu religious tourism place and famous for Lord Krishna birthplace, temple and activates. We are placing some information regarding Mathura Vrindavan Tour Packages. During Mathura Vrindavan tour, you may cover the following places. Place to Visits : Mathura : Lord krishna Birthplace, Dwarkadhish Temple, Birla Temple, Mathura Museum, Yamuna Ghat's Vrindavan: Bankey Bihari Temple, Iskcon Temple, Radha Ballabh Temple, Prem Mandir, Nidhi Van, Kesi Ghata and Yamuna River etc. P a g e | 2 Mathura Vrindavan Yaatraa Gokul: Childhood living place of lord Krishna Near Mathura Nand Gayon: Village of lord krishna relatives Goverdhan: Goverdhan Mountain and Parikrma, Radha Kund, Kusam Sarowar Barsana: Birthplace of Radha Rani and Temples Radha Rani: Famous Temple of Radha Rani near Mathura Bhandiravan: Radhak Krishn Marriage Place, Near Mant Mathura TOURIST PLACE AT DISTRICT MATHURA MATHURA What to See SHRI KRISHNA JANMA BHUMI : The Birth Place of Lord Krishna JAMA MASJID : Built by Abo-inNabir-Khan in 1661.A.D. the mosque has 4 lofty minarets, with bright colored plaster mosaic of which a few panels currently exist. VISHRAM GHAT : The sacred spot where Lord Krishna is believed to have rested after slaying the tyrant Kansa. DWARKADHEESH TEMPLE : Built in 1814, it is the main temple in the town. During the festive days of Holi, Janmashthami and Diwali, it is decorated on a grandiose scale. GITA MANDIR : Situated on the city outskirts, the temple carving and painting are a major attraction. GOVT. MESEUM : Located at Dampier Park, it has one of the finest collection of archaeological interest. -

SWAMI ANANTACHARYAJI of Vrindavan, India

RAMAYANA PRAVACHAN By SWAMI ANANTACHARYAJI Of Vrindavan, India JAI SITA RAM Dates: Sunday September 27 to Saturday October 3, 2009 Time: Sunday: 4:00 PM to 7:00 pm Monday to Friday: 7:00 pm to 9:00 pm Saturday (Pooran Ahuti): 11:00 AM to 2:00PM Place: The Hindu Temple of Metropolitan Washington, D. C. 10001 Riggs Road, Adelphi, MD 20783 Tel: 301-434-1000, 301-445-2165 Preeti Bhoj (Dinner) Everyday after discourse For more information, please contact Bhagyawati Sharma 301-262-7239, Chandrawati Mishra 301-972-6329, Sheela Misra 301-340-2983, Sharmishta Gupta 301-983-0355, Mamta Tiwari 301-774-6365 Directions: From Beltway (495) take New Hampshire Avenue (Exit 28) going North. After about 2 blocks take right at Powder Mill Road. At the next traffic light take right on Riggs Road. The temple is on your left prior to beltway over bridge. RADHA KRISHNA GATIMAM KRISHNA BHAKTI SEWA SANGH BURJA ROAD, CHATANIYA VIHAR, VRINDAVAN, UP. INDIA Phone international: +91 - 565 6454394 Mobile: +91 9897198291 Website: www.radhamadhavdivyadesh.org TAX ID: 14-1862809 Krishna Bhakti Sewa Sangh was founded by Swami Anantacharaya Ji Maharaj. With your much appreciated co-operation, Swamiji has established this organization and ashram in Vrindavan with the divine purpose of providing genuine education in Vedic scriptures such as The Srimad Bhagavat, The Ramayan, The Bhagavat Gita to preach The Sanatan Dharma around the world. Swamiji has been spreading Sanatan Dharma outside of India since 1983, having done Katha in 35 out of the 50 states of USA. He has also preached in Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, China, Canada, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Philippines, West Indies and Panama. -

Historical Timeline of Hinduism in America 1780'S Trade Between

3/3/16, 11:23 AM Historical Timeline of Hinduism in America 1780's Trade between India and America. Trade started between India and America in the late 1700's. In 1784, a ship called "United States" arrived in Pondicherry. Its captain was Elias Hasket Derby of Salem. In the decades that followed Indian goods became available in Salem, Boston and Providence. A handful of Indian servant boys, perhaps the first Asian Indian residents, could be found in these towns, brought home by the sea captains.[1] 1801 First writings on Hinduism In 1801, New England writer Hannah Adams published A View of Religions, with a chapter discussing Hinduism. Joseph Priestly, founder of English Utilitarianism and isolater of oxygen, emigrated to America and published A Comparison of the Institutions of Moses with those of the Hindoos and other Ancient Nations in 1804. 1810-20 Unitarian interest in Hindu reform movements The American Unitarians became interested in Indian thought through the work of Hindu reformer Rammohun Roy (1772-1833) in India. Roy founded the Brahmo Samaj which tried to reform Hinduism by affirming monotheism and rejecting idolotry. The Brahmo Samaj with its universalist ideas became closely allied to the Unitarians in England and America. 1820-40 Emerson's discovery of India Ralph Waldo Emerson discovered Indian thought as an undergraduate at Harvard, in part through the Unitarian connection with Rammohun Roy. He wrote his poem "Indian Superstition" for the Harvard College Exhibition of April 24, 1821. In the 1830's, Emerson had copies of the Rig-Veda, the Upanishads, the Laws of Manu, the Bhagavata Purana, and his favorite Indian text the Bhagavad-Gita. -

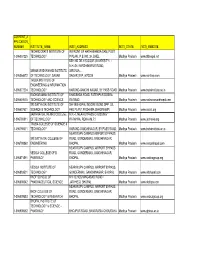

Y CURRENT a PPLICATION NUMBER INSTITUTE NAME

CURRENT_A PPLICATION_ NUMBER INSTITUTE_NAME INSTI_ADDRESS INSTI_STATE INSTI_WEBSITE TECHNOCRATS INSTITUTE OF IN FRONT OF HATHAIKHEDA DAM, POST 1-396057225 TECHNOLOGY PIPLANI, P.B. NO. 24, BHEL Madhya Pradesh www.titbhopal.net BEHIND DR.H.S.GOUR UNIVERSITY, N.H.-26, NARSHINGPUR ROAD, SWAMI VIVEKANAND INSTITUTE SIRONJA, 1-396064472 OF TECHNOLOGY, SAGAR SAGAR (M.P.) 470228 Madhya Pradesh www.svnitmp.com TRUBA INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING & INFORMATION 1-396077204 TECHNOLOGY KAROND-GANDHI NAGAR, BY PASS ROAD Madhya Pradesh www.trubainstitute.ac.in RADHARAMAN INSTITUTE OF BHADBHDA ROAD, FATEHPUR DOBRA, 1-396649415 TECHNOLOGY AND SCIENCE RATIBAD Madhya Pradesh www.radharamanbhopal.com SRI SATYA SAI INSTITUTE OF SH-18,BHOPAL INDORE ROAD,OPP. OIL 1-396697631 SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY FED PLANT,PACHAMA SEHORE(MP) Madhya Pradesh www.sssist.org JAWAHARLAL NEHRU COLLEGE N.H.-7, NEAR BYPASS CROSSING 1-396790811 OF TECHNOLOGY RATAHRA,,( REWA (M.P.)) Madhyya Pradesh www.jnctrewa.orgjg TRUBA COLLEGE OF SCIENCE & 1-396798671 TECHNOLOGY KAROND-GANDHINAGAR, BY PASS ROAD. Madhya Pradesh www.trubainstitute.ac.in NEAR RGPV CAMPUS AIRPORT BY-PASS SRI SATYA SAI COLLEGE OF ROAD, GONDERMAU, GANDHINAGAR, 1-396798862 ENGINEERING BHOPAL Madhya Pradesh www.ssscebhopal.com NEAR RGPV CAMPUS, AIRPORT BYPASS VEDICA COLLEGE OF B. ROAD, GONDERMAU, GANDHINAGAR, 1-396871591 PHARMACY BHOPAL Madhya Pradesh www.vedicagroup.org VEDICA INSTITUTE OF NEAR RGPV CAMPUS, AIRPORT BYPASS, 1-396893501 TECHNOLOGY GONDERMAU, GANDHINAGAR, BHOPAL Madhya Pradesh www.vitbhopal.com RKDF SCHOOL OF NH-12,HOSHANGABAD ROAD 1-396898342 PHARMACEUTICAL SCIENCE JATKHEDI, BHOPAL Madhya Pradesh www.rkdfsps.com NEAR RGPV CAMPUS, AIRPORT BYPASS RKDF COLLEGE OF ROAD, GONDERMAU, GANDHINAGAR, 1-396899583 TECHNOLOGY & RESEARCH BHOPAL Madhya Pradesh www.vedicagroup.org BHOPAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY & SCIENCE - 1-396908662 PHARMACY BHOJPUR ROAD, BANGRASIA CHOURAHA Madhya Pradesh www.globus.ac.in OPP.