Worst Midwest Drought in 17 Years Is Withering Crops, Slowing Cargo

By SCOTT KILMAN Staff Reporter of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL August 4, 2005; Page A1

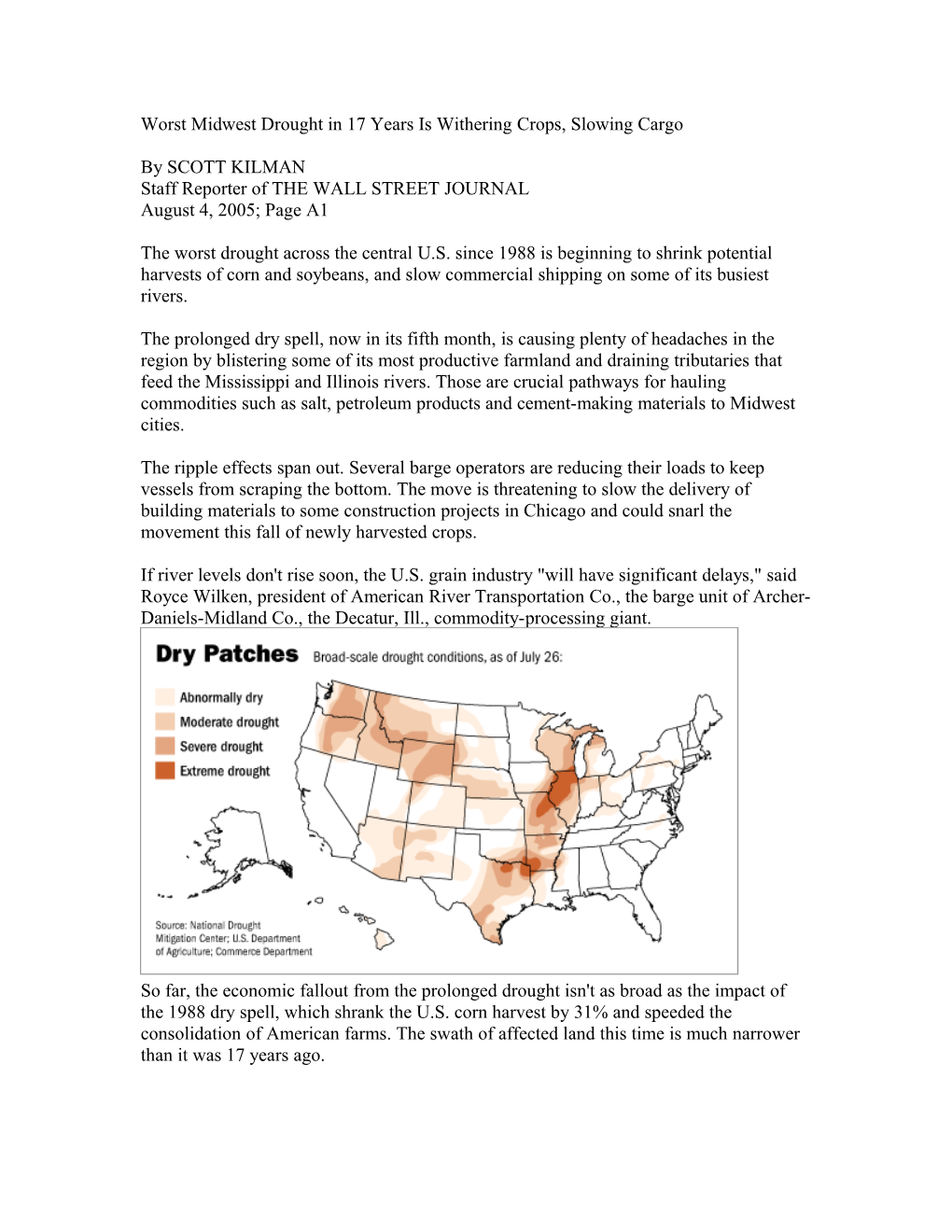

The worst drought across the central U.S. since 1988 is beginning to shrink potential harvests of corn and soybeans, and slow commercial shipping on some of its busiest rivers.

The prolonged dry spell, now in its fifth month, is causing plenty of headaches in the region by blistering some of its most productive farmland and draining tributaries that feed the Mississippi and Illinois rivers. Those are crucial pathways for hauling commodities such as salt, petroleum products and cement-making materials to Midwest cities.

The ripple effects span out. Several barge operators are reducing their loads to keep vessels from scraping the bottom. The move is threatening to slow the delivery of building materials to some construction projects in Chicago and could snarl the movement this fall of newly harvested crops.

If river levels don't rise soon, the U.S. grain industry "will have significant delays," said Royce Wilken, president of American River Transportation Co., the barge unit of Archer- Daniels-Midland Co., the Decatur, Ill., commodity-processing giant.

So far, the economic fallout from the prolonged drought isn't as broad as the impact of the 1988 dry spell, which shrank the U.S. corn harvest by 31% and speeded the consolidation of American farms. The swath of affected land this time is much narrower than it was 17 years ago. Moreover, the economic damage of the drought is being partly offset by a marked easing of a separate drought that has plagued farms and ranches across the Northern Plains for more than five years. Most economists, for example, expect the rate of overall food inflation to cool this year, largely due to weakening cattle prices.

The Midwest state hardest hit by the drought is Illinois, typically the nation's biggest producer of soybeans and the second-largest producer of corn, behind Iowa. Fields across much of Illinois have received less than half of their normal rainfall since March, making them the driest since the drought of 1988.

According to state authorities, tens of thousands of Illinois farmers already have lost one- third of their potential crops, which is spreading a chilling effect on merchants in farm towns across the state. A survey by the U.S. Department of Agriculture found 55% of the Illinois corn crop in very poor or poor condition the last week of July, as well as 34% of the soybean crop and 74% of Illinois pastures, upon which livestock graze.

"We're putting off as many spending plans as we can," said John Ackerman, a 44-year- old farmer in Morton, Ill., who had wanted to buy a chemical sprayer for his apple orchard but isn't. "It's amazing how one bad year can set you back."

Managers of many Illinois grain elevators, which buy crops from farmers and sell to processors, are resigning themselves to lower grain volumes -- and profits -- this year. Minier Cooperative Grain Co., in Minier, Ill., has tabled plans to invest in new grain storage tanks.

At the nearby Deere & Co. farm-equipment dealership, the sale of "new stuff is coming to a screeching halt," said Rick Cross, owner of Cross Implement Inc. in Minier.

Production of corn nationwide should fall 16% this year to 9.9 billion bushels from last year's record harvest of 11.8 billion bushels mostly due to drought damage in Illinois, eastern Iowa and Missouri, said Dan Basse, president of AgResource Co., a commodity forecasting concern in Chicago.

U.S. companies use corn to do everything from sweetening soda pop to making ethanol fuel to fattening hogs and chickens for slaughter.

Any return of rainfall now would do little to help the corn crop, which passed through its pollination period in July when it is the most sensitive to weather conditions. However, soybean plants continue to bloom through August, making it possible for that crop to recover somewhat if rains return.

Based on current conditions, Stewart Ramsey, an economist at Global Insight Inc., said he expects U.S. soybean production to fall 10.8% to 2.8 billion bushels from last year's record harvest of 3.14 billion bushels.

The shrinking harvest forecasts are fueling worry on Wall Street that Midwest-based grain processors will have fewer crops to process next year, and that meat companies such as Tyson Foods Inc. and Smithfield Foods Inc. will see their costs of feeding livestock climb.

A Smithfield spokesman said there aren't any drought-related problems so far at its hog farms. A Tyson spokesman declined to comment on the drought's effect on future costs, although he noted that the company's grain costs during the nine-month period ended July 2 were lower than the year-ago period.

Christine L. McCracken, an analyst at FTN Midwest Securities Corp., has shaved her earnings estimates for rival poultry processors Tyson and Sanderson Farms Inc. to reflect rising grain costs.

Mike Cockrell, chief financial officer of Sanderson Farms, Laurel, Miss., said corn and soybeans represent roughly 40% of the company's cost of producing chicken. "Most definitely, higher grain costs will impact the [chicken] industry and the company," he said.

Still, as crops in Illinois, Missouri and Wisconsin are wilting, many fields in places such as Nebraska, Minnesota and western Iowa, for example, are thriving.

What's more, the appearance of the Illinois-centered drought coincides with the fading of the five-year drought across the Northern Plains. Many Montana farmers, for example, are reaping record-large yields from their wheat fields this summer. Pasture conditions are improving enough there and across the Northern Plains for many ranchers to think about rebuilding their cattle herds. Likewise, the reservoirs in Montana and the Dakotas that feed the Missouri River are slowly refilling.

The upshot is that commodity analysts are projecting that corn and soybean harvests this year should still be relatively large but just not a repeat of last year's records.

Most economists expect food prices to climb at a slower rate than the 3.4% increase of last year, which was the biggest increase since 1990, when retail food prices climbed 5.8%.

Michael J. Swanson, an agricultural economist at bank Wells Fargo & Co., said he expects U.S. food prices to rise between 2.5% and 3% this year. Mr. Ramsey, the economist at Global Insight, said he expects a smaller increase of between 2% and 2.5%.

One of the biggest changes in the grocery bill from last year is the price of beef. The retail price of beef jumped nearly 12% last year amid strong consumer demand and tight supplies. This year, the USDA expects retail beef prices to climb just 1% to 2%. A beef shortage is easing in part because the U.S. in July ended a two-year-old, mad cow-related ban on importing live Canadian cattle. With the prospect of good crops in other parts of the country, crop prices aren't rising enough to compensate many Illinois grain farmers for their losses. Corn prices are flat compared with a year ago at this time, while soybean prices are up only 17% compared with the year ago.

Some exceptions are prices of organic grains, which are jumping because much of these crops are raised in the drought area -- and so supplies are tight. The price of organic corn, for example, is 60% higher than last year, increasing the cost of feeding organic livestock so much that some farmers are delaying plans to expand their herds.

Another crop suffering disproportionately from the drought is pumpkin. Most of the pumpkins used to make pie are grown around Morton, Ill., home to a Libby's pumpkin plant owned by Nestlé SA.

A Nestlé spokeswoman said it's "still too early to tell" how much pumpkin production will fall. But local sponsors of an October "Punkin Chuckin" contest -- in which machines are used to fling the fruit -- are already worried about their ammunition.

"We may be hurting for pumpkins," said Mike Badgerow, executive director of the Morton Chamber of Commerce.

Write to Scott Kilman at [email protected]