Invasion Biology – Assignment 2: A review of an Expert System for screening species introductions into the Fynbos Biome David Vaughan, 2651582

Introduction:

Expert systems are intended to be knowledge-based, in the form of a computer programme which contains specific knowledge on a subject or related subjects of one or more professionals who pioneered the information [42]. This type of programme was initially invented in the 1960s as a type of artificial intelligence, but became more commercial throughout the 1980s [42].

Generally an Expert system is made up of a set of rules, applied to specific information and problems to provide not only analysis but resolution in the form of recommended courses of action to take [42]. A related type of programme is the computer Wizard [42]…and something that many computer users find extremely irritating at the best of times.

As this is an assignment in the understanding and training of Expert systems, I have attempted to provide as much information as possible to answer the questions and fulfil the rules set out in “An Expert System for Screening Potentially Invasive Alien Plants in South African Fynbos (1995)” by K. C. Tucker and D. M. Richardson, published in the Journal of Environmental Management 44, 309 – 338.

Five plant species were randomly selected from a supplied list of plants of both Widespread and Narrow distribution. Two plant species selected were required to have a Widespread distribution.

Initially, the Expert system seemed to operate efficiently, however, as is mentioned in more detail in the conclusion of this document, it was found that the rigidity of the rules set out in the Expert system could not make effective provision for the flexibility of certain criteria which rely on several area, species and environmentally specific factors. In other words there was rarely one answer for the questions asked of the system, leading to personal interpretation of questions and answers-to-fit scenarios, which, can sway the rule outcomes to either extreme depending on the conservativeness of the user.

Additionally, rare and isolated plant species, like the Banksia spp. indicated in the random selection for this assignment, are extremely difficult to run through the Expert system on a species level, as information regarding biology, ecology and adaptations to fire may be incomplete or completely lacking, which was found to render the model prematurely insignificant, even if the future of these species reveals them to be invasive in similar Fynbos biomes in South Africa. Also, it is considered that protected species such as the two selected Banksia spp., would be governed by international law, prohibiting the legal sale of, or trade, reducing the risk of intentional introduction. It is therefore unlikely that such species would be introduced accidentally.

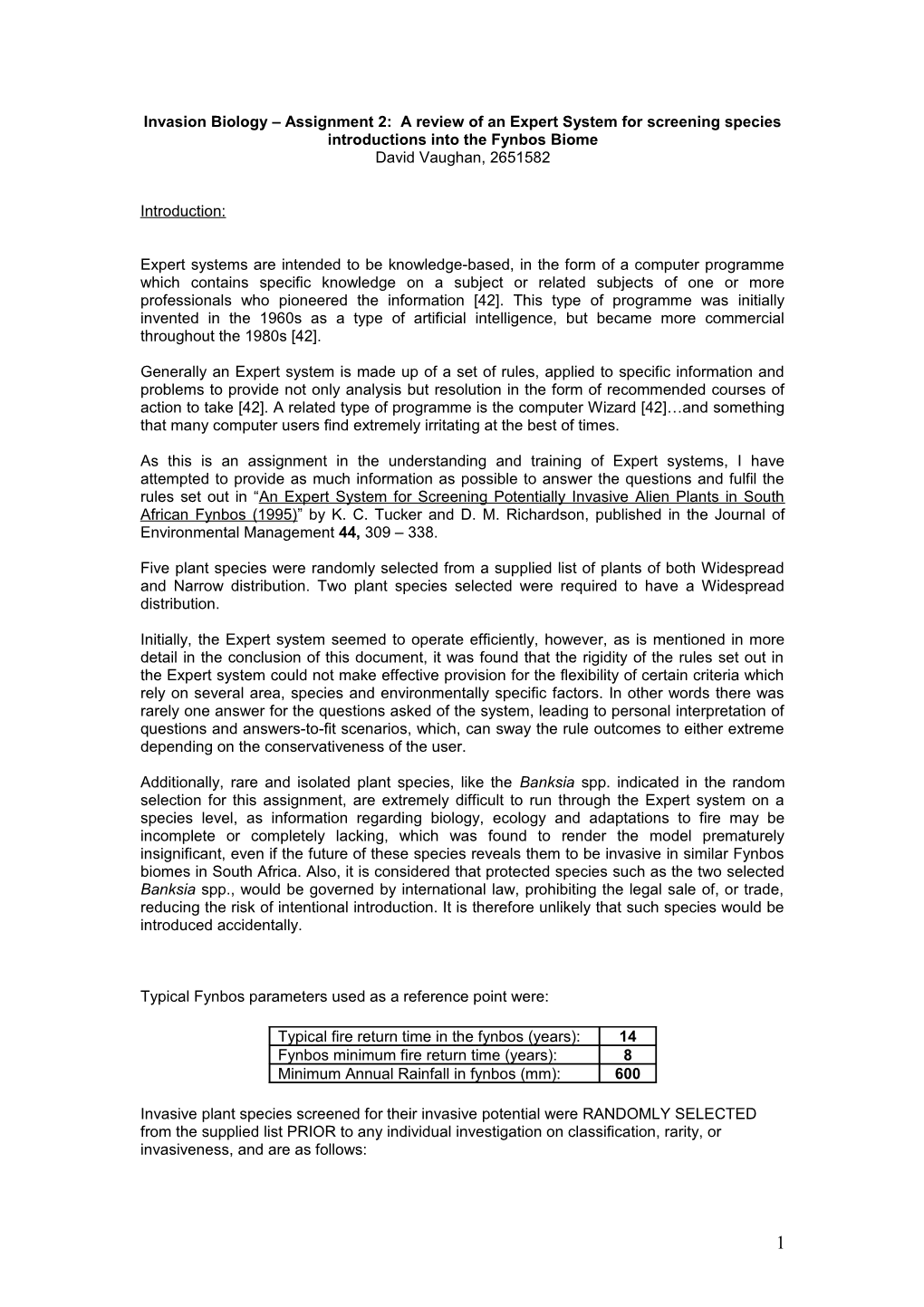

Typical Fynbos parameters used as a reference point were:

Typical fire return time in the fynbos (years): 14 Fynbos minimum fire return time (years): 8 Minimum Annual Rainfall in fynbos (mm): 600

Invasive plant species screened for their invasive potential were RANDOMLY SELECTED from the supplied list PRIOR to any individual investigation on classification, rarity, or invasiveness, and are as follows:

1 Species to screened Distribution Status Country 1) Acasia cyclops Widespread Western Australia 2) Acacia longifolia Widespread Eastern Australia 3) Atremisia californica Narrow distribution USA 4) Banksia scabrella Narrow distribution Western Australia 5) Banksia tricuspis Narrow distribution Western Australia

1) Acasia longifolia, The Sydney Golden Wattle.

[1] Form:

Acacia longifolia is a semi-erect perennial tree with an active growth period in Spring and Summer [1]. The foliage of A, longifolia is retained during Autumn, is green in colour [2], of relatively fine texture, yet dense in Winter as well as Summer [1]. Leaves are simple and between 5 and 15cm long, are linear-lanceolate (meaning symmetrical in length, long, ending at a point), and the 2 or 3 longitudinal veins are more prominent than the other smaller veins [1]. Growth is rapid and the tree grows multiple stems at a time [1]. Total height at a maturity of 20 years can be up to 6 meters tall. General height ranges from 3 to 7 meters tall [1]. Flowers grow in conspicuous spikes of between 2 and 4cm long, are yellow in colour [1,2] and can have a strong pollen smell. The fruits and seeds are usually a brown colour and are well disguised amongst the foliage [1].

Biology:

A. longifolia is not known to be toxic [1] and does not require a cold dormant period during Winter. A. longifolia is drought resistant, and adapted to course, medium and fine soil types with a pH range of an acidic 6.0 to an alkaline 8.3.[1] A. longifolia can tolerate a high planting density of up to a maximum of 1200 per Acre, and can withstand temperatures down to minus 10°C [1]. A. longifolia flowers in Summer and has a high fruit and seed abundance (up to 15 000 seeds per kilogram) from Summer to Autumn [1]. Seeds and fruits have a high persistence. Propagation is usually by seed, however cuttings are very successful, as is propagation by bare root, making A. longifolia difficult to eradicate once established [1]. A. longifolia also has the ability to sprout from its trunk and base once chopped down, if not correctly treated [1].

Habitat:

Acacia longifolia prefers sandy, coastal areas up to and altitude of 150 m and can be common along sandy river banks in the Western Cape in South Africa [1].

Question 1: Is intense fire a characteristic of the home environment and does the area have a fire-adapted biota? Yes, intense fire is a (relatively new) characteristic of the native environment of Acacia longifolia based on the historical fact that Australian Aboriginal people have used increasing burning practices over the last 50 000 years to affectively encourage an increased number of seed-producing plants such as A. longifolia as a food source [4]. The native area sustains a more fire-adapted biota as a result [4].

2 Acacia longifolia is not fire resistant, however has a medium fire tolerance [1] A total (100%) scorching of the tree canopy by fire is effective in killing adult trees [3]. Fewer A. longifolia seeds germinate under parent plants in the absence of fire, and up to 90% of the seed bank can germinate after the destruction of the parent plants after a fire [1], however, it is indicated that this depletion of the seed bank could be used as an integrated management strategy for its control [1,3]. If the fire turn over period in Fynbos systems is indicated as every 14 years, in addition to a fast maturation of the adult plants within a 20 year period, if many seeds and a successfully high intensity seed bank is establishes within the times between fires, this species could most certainly be seen as strengthened by the natural fire return periods.

Question 2: What is the expected fire return time in the home environment?

Fire-return intervals are dictated by the rate at which fuel accumulates, such as dry grass, leaf litter, twigs etc, not only at the site of study, but also other surrounding areas, as fire can spread rapidly from one area to another. Another factor is the source of possible ignition, including human intervention and accidental ignition [5].

Finding an exact known fire-return time for A. longifolia has been difficult, so it was opted for, to investigate the known or suggested fire-return times for the native environment where this plant is known to live in Eastern and South Eastern Australia. According to a study done by Watson & Wardell-Johnston 2004 [6], Study areas within one plant community within the Girraween National Park in South Eastern Queensland, Australia, showed a recent fire-return interval of between 4 to 9 years [6]. It is with this information that for this investigation using the expert system, the suggested 40 year conservative estimate replacement figure be replaced with the mode between the suggested 4 to 9 years, which would be 6.5 years.

Question 3: Is the home environment nutrient poor?

A. longifolia is adapted to a wide range of soil conditions and is a Nitrogen fixer [1]. Its home environment is particularly low in N and P, and is nutrient poor. By fixing nitrogen through the symbiotic relationship with Nitrogen-fixing bacteria, A. longifolia can easily adapt to a variety of soil types [7].

Question 4: What is the annual rainfall in the home environment?

Using the map supplied by Http://www.australiatravelsearch.com.au/trc/facts.html accessed on 2/7/06, 16:28, if the entire Eastern half of Australia is to be taken as the home range of A. longifolia, annual rainfall would include areas with 100mm, 400mm, 800mm, 1600mm, and 2400mm. If a mean of the total is calculated, then 1060mm is the average annual rainfall category for the entire Eastern half of Australia.

Question 5: In what type of vegetation does the species occur in its home range?

3 A. longifolia more often makes up the understory of coastal forest communities and dry- forest communities in Eastern and South Eastern Australia [8].

Question 6: In its home environment, the species typically occurs as…

Weedy [1].

Question 7: Is the species a habitat specialist?

Yes, A. longifolia is restricted to lower-lying areas, though is not necessarily dictated by the soil type [1].

Question 8: Is the habitat specialisation biotically determined?

Yes, as per above [1].

Question 9: Is it likely that any biotic agents will have the same effects in fynbos?

Yes. As A. longifolia is restricted by height above sea-level [1] but is adapted specifically to coastal forest areas, the affects of the location on the fynbos will be similar to the native areas where A. longifolia are found, though, higher-altitude fynbos areas are at lower risk of invasion [1].

Question 10: Is this habitat restricted in fynbos?

Yes. As mentioned above regarding high altitudes where fynbos is unlikely to be invaded.

Question 11: What is the principle dispersion vector?

A. longifolia is primarily dispersed by water and birds [1], although the seeds are known to be highly attractive to a wide range of animal vectors, [9] and can be passed successfully through the stomach of these animals [1]. Ants are also known as vectors of seed dispersal.

An interesting point raised by C. S. Blaney and P. M. Kotanen 2001 [10], is the importance of including the rates of attacks on seeds of potentially invasive species by their natural enemies or granivores. Seed dispersal success in areas devoid of the natural granivores however does not significantly contribute to invasion success but does play an important role. This is not indicated in the Expert System of Tucker and Richardson, used as a model for this assignment. Additionally, the rate of flower and fruit production, which has a direct impact on seed production, can increase the chances of invasion success. A. longifolia has an 8 times more successful total production of ripe viable seed in South Africa, than its native country Australia [11]. The effects of natural enemies on the production of seed also needs to be taken into account.

The following table is taken from Mack et al. 2000 [11]:

Question 12: Does the species require a specialist dispersal vector?

4 As already indicated, various vertebrate vectors could be responsible for dispersal [9], therefore no one specific specialist species is identified. For the function of this assignment, it is opted to choose “generalist” on these grounds.

Question 13: Is there an equivalent dispersal vector in fynbos?

Yes, though no specific reference to publication can be made. It is assumed that native bird species and ants are responsible. In addition, humans must be seen as vectors, chopping down A. longifolia on the Cape Flats to be used as firewood and in the process, while dragging bundles of fuel long distances, spread the seeds unknowingly.

Question 14: Does the seed have adaptations for dispersal over long distances by wind?

No [1].

Question 15: In its home environment, the annual seed production is (low/medium/high)?

High [11]. Question 20: Relative to the home environment, seed predation is likely to be …

Lower [11].

Question 22: The juvenile period of the species is…, shorter than the fynbos fire-return time?

Yes, 5 years [12].

Total = HR 1 (High Risk 1) – no discussion needed.

2. Acacia cyclops, the Rooikrans.

[15]

Form

Acacia cyclops A. Cunn. ex G. Don, or Rooikrans, is related to A. longifolia. A. cyclops is a dense multi-stemmed and evergreen bushy shrub or small tree between 3m and 8m tall with a more rounded crown appearance [13]. In coastal areas, such as areas along the South African Western Cape coast, it can form a dense hedge of 0.5m tall [13]. The seedpods do not fall from the tree when ripe, but remain to be optimally exposed to dispersal vectors such

5 as birds [13]. A. cyclops has phyllodes instead of true leaves [14]. Phyllodes are modified petioles or leaf stems [14]. The phyllodes are generally 4cm – 8cm long in A. cyclops, and about 6mm – 12mm wide [14]. Unlike other Acacia species, A. cyclops flowers over a long period of time, from Spring to Summer [14], but produces relatively small numbers of flower head-clusters.

Biology

A. cyclops can tolerate wind and drought as well as salt spray from coastal areas and sand commonly found in coastal sand dunes [13]. Although relatively slow growing, once established through the spreading of seeds into an area by birds, it is difficult to get rid of [13]. Seeds are characteristic and encircled by a double row of red or orange flesh called the aril [15]. The seed pods curl up when dry [15]. It is interesting to note that the red colour of the aril is brightly coloured to aid in dispersal by birds which may more easily pick up the contrasting colour amongst the foliage, and, the hard part of the seed is easily passed through the digestive tract of the bird unharmed [16]. So why eat the seeds in the first place? It is known that the aril of the seeds of the related Acacia verticillata are rich in lipid-structures called elaiosomes [16]. Although birds may well benefit from digesting elaiosomes, ants too take the seeds into their nests and feed on the elaiosomes, discarding the seed itself, which is left to germinate [16].

Habitat

A. cyclops is found growing on both soils with a higher salt content, and also calcareous soils, tolerating salt spray similarly to A. longifolia, wind, and generally poor soil conditions [17]. This invasive acacia is found naturally in Western Australia in Winter rainfall areas, making it a prime candidate as an invasive in the Western Cape of South Africa [18].

Question 1: Is intense fire a characteristic of the home environment and does the area have a fire-adapted biota?

Yes, although Acacia longifolia is not fire resistant like A. longifolia. Seeds are resistant to fire and may germinate after fires associated with Fynbos areas in the Western Cape [18].

Question 2: What is the expected fire return time in the home environment?

“fire frequency and occurrence is affected by a complex range of interrelated factors, including seasonal rainfall conditions and associated build up of fuels, ignition sources and land use values”[19]

Fire-return time varies in Western Australia as a result of the above information quote. The suggested time varies from a minimum of 5 years to 20 – 50 years [19]. From this information, the more conservative estimate has been adopted for use in this assignment (5 years).

Question 3: Is the home environment nutrient poor?

“ There is probably no continent with soils so critically low is essential plant nutrients as Australia” [20].

Yes, the home environment of Western Australia is nutrient poor.

Question 4: What is the annual rainfall in the home environment?

For continuity, using the map originally used for A. longifolia, as well as averaging the information it supplies for the Western half of the Australian continent, The rainfall figure used for this assignment will be 433.33ml.

Question 5: In what type of vegetation does the species occur in its home range? Mediterranean-type forest [21].

6 Question 6: In its home environment, the species typically occurs as…

Potentially weedy [22].

Question 7: Is the species a habitat specialist?

Yes, Coastal forest areas including poor quality soil types and sand dunes [23].

Question 8: Is the habitat specialisation biotically determined?

Unknown. Probably not.

Question 10: Is this habitat restricted in Fynbos?

No.

Question 11: What is the principle dispersion vector? Birds and Ants [16].

Question 12: Does the species require a specialist dispersal vector?

No specific species is given regarding the birds which feed on the seeds in South Africa, though many softbills may well feed on its seeds. Regarding ants, there is a split in the expert system diagram at this question where vertebrates and invertebrates are dealt with towards two different outcomes. To be more conservative, and since birds can disperse the seeds at greater distances, invertebrates (ants) will be ignored. The category of “generalist” is therefore chosen as the most appropriate.

Question 15: In its home environment, the annual seed production is (low/medium/high)?

High, up to 3650/m² [24].

Question 20: Relative to the home environment, seed predation is likely to be …

Lower [11].

Question 22: The juvenile period of the species is…, shorter than the fynbos fire-return time?

Yes, 3 years [25].

Total = HR 1 (High Risk 1) – though not entirely reflective. Certain criteria to get to this end- point were vague.

3. Atremisia californica, California sagebush.

[26] [27] [27]

7 Form

This dense and multi-stemmed shrub [27] is native to central and Southern California in the United Sates of America. [26] It is evergreen and grows to about 1m – 4m tall and 1m – 2m wide [26]. The foliage is grey in colour [26]. The leaves are small, simple, and are divided into linear lobes [27]. The leaves are aromatic, and often used in teas etc. [26, 27]. Flowers are very small and usually arranged in small racemes [27]. The colour of the flowers ranges from yellow through to pink [27]. “The fruits are small achene” [27], which is a small dry fruit containing a single seed which does not open at maturity [28].

Biology

Artemisia californica has light wind-dispersed seeds which can travel great distances [29]. It is interesting to note that the seeds can germinate if allowed to fall onto moist soil at the surface, but if the seeds are buried, they usually only germinate after being exposed to what is known as the charred wood-leachate, which happens as result of a fire [29]. A. californica can re- sprout from the roots if the plant above ground is damaged [29]. This shrub is also adapted to the coastal environment and therefore can withstand salt spray and wind [28].

Habitat

A. californica is commonly found in Mediterranean conditions which have a “maritime influence” [29], i.e., near the sea. This shrub is also only found below a height elevation of 762m and commonly growing on a range of slopes with a range of soil types from shallow sandy soils to clay, loam and gravel soil-types [29].

Question 1: Is intense fire a characteristic of the home environment and does the area have a fire-adapted biota?

Though vague, Yes [29].

Question 2: What is the expected fire return time in the home environment?

10 – 30 years [30]. Minimum fire-return time used for fynbos in this assignment is 8 years, therefore the minimum fire-return time suggested here of 10 years will be classified as “long” for the purpose of the expert system evaluation.

Question 3: Is the home environment nutrient poor?

Generally poor [29].

8 Question 4: What is the annual rainfall in the home environment?

250 –450mm per year [29]. This is lower than the given amount of 600mm for this assignment for fynbos, and although the schematic of the expert system indicates that this plant therefore falls under Low Risk 4 category, an increase in rainfall may have an increasing affect on its reproductive capability as indicated in the discussion about its biology, therefore, I continue down to question 5.

Question 5: In what type of vegetation does the species occur in its home range?

Coastal scrub (Mediterranean-type scrubland) [29].

Question 6: In its home environment, the species typically occurs as…

Dominant within the Mediterranean-type scrubland, but no indication of being weedy is given [29]. In this regard, and as a result of interpretation of information supplied in [29], it is opted to accept the choice of “isolated individuals but occasionally thicket-forming or ‘weedy’”, as given in the expert system.

Question 11: What is the principle dispersion vector?

Wind [29].

Question 14: Does the seed have adaptations, such as low seed-wing loading?

The seeds are light and therefore must be adapted to wind dispersal [29], therefore Yes.

Question 15: In its home environment, the annual seed production is (low/medium/high)?

“Achenes are tiny (about 60 micrograms) and in bulk amount to about 14,300,000 seeds/kg” [31]. High.

Question 20: Relative to the home environment, seed predation is likely to be …

Lower, since natural seed predators are absent in the fynbos biome, however, no reference for this can be provided.

Question 22: The juvenile period of the species is…, shorter than the fynbos fire-return time?

“ Perennial”[32], the definition of which is a plant which has a life-cycle that extends indefinitely beyond two growing seasons, and the parent plant does not die after flowering [33]. As no definite indication of time to maturity of seedlings could be found in countless searches, I settled on the definition of the plants given perennial status characteristics to service the requirements of this question, therefore, to be conservative, if the time no shorter than two growing seasons (2 years) is given as a minimum, the juvenile period is shorter than the fire-return time given of 8 years in fynbos.

Therefore, it is concluded that this species could be High Risk in certain areas only, and if fire- return times are infrequent.

4. Banksia scabrella, the Burma Road Banksia.

9 [35]

Form

B. scabrella is a shrub occurring in isolated populations in Western Australia [34]. The shrub is 0.6 to 2m tall with creamy yellow or purple flowers [35]. The shrubs have many branches [35].

Biology

Very little information at all is available for B. scabrella. For the function of this assignment, I will be using more general information regarding the genus Banksia.

The flower spikes of Banksia spp. dry up over time and form what looks like a cone [37]. Very few of the flowers actually produce fruits. The fruits look like “woody follicles” which are embedded into the cone like structure [37]. The flowers are pollinated by nectar feeding birds. The flowers produce large amounts of this nectar [37]. The woody follicle contains the seeds and in some species, when ripe, splits to release the seeds [37]. In other species, the follicle can only split to release the seeds when subjected to fire [37].

Habitat

B. scabrella is found growing in white, yellow and grey sand in isolated upland areas in Western Australia [36]. This plant is Cites listed as priority four endangered species [35].

Question 1: Is intense fire a characteristic of the home environment and does the area have a fire-adapted biota?

Yes [37]

Question 2: What is the expected fire return time in the home environment?

As for Acacia Cyclops, the more conservative estimate of 5 years is shared [19].

Question 3: Is the home environment nutrient poor?

10 Yes [20, 37, 36].

Question 4: What is the annual rainfall in the home environment?

As for A. cyclops: 433.33ml.

This is again lower than the given amount of 600mm for this assignment for fynbos, and the schematic of the expert system indicates that this plant therefore falls under Low Risk 4 category.

Since this is an extremely rare species occupying a very small localised habitat in Western Australia (see map below), and including the fact that there is very little information at all on this specific Banksia species (five plant data-bases searched: Global Biodiversity Information Facility – http://www.secretariat.gbif.net , ITIS USA – http://www.itis.usda.gov , Species 2000 – http://www.sp2000.org , China Species Information Service (CSIS) – http://www.chinabiodiversity.com , Wildfinder – http://www.worldwildlife.org), until further evidence suggests that it may function at a higher risk level than suggested, this species will be termed Low Risk.

[35] The location of Banksia scabrella in Western Australia.

5. Banksia tricuspis, the Pine Banksia.

11 [38] [39]

Form

B. tricuspis is a shrub or small tree that only occurs in a small geographical range in Western Australia [40]. The plant stands 1.2 – 4m tall and has yellow-orange flowers [41] and shares the same conservation status as B. scabrella, growing in very similar general conditions [41].

Biology

As for B. scabrella [37].

Habitat

Found growing in similar conditions to B. scabrella [41].

Question 1: Is intense fire a characteristic of the home environment and does the area have a fire-adapted biota?

Yes [37]

Question 2: What is the expected fire return time in the home environment?

As for Acacia cyclops, the more conservative estimate of 5 years is shared [19].

Question 3: Is the home environment nutrient poor?

Yes [20, 37, 36].

Question 4: What is the annual rainfall in the home environment?

As for A. cyclops: 433.33ml.

This is again lower than the given amount of 600mm for this assignment for fynbos, and the schematic of the expert system indicates that this plant therefore falls under Low Risk 4 category.

12 Since this is an extremely rare species (again) occupying a very small localised habitat (15km²) in Western Australia (see map below), and including the fact that there is very little information at all on this specific Banksia species (five plant data-bases searched: Global Biodiversity Information Facility – http://www.secretariat.gbif.net , ITIS USA – http://www.itis.usda.gov , Species 2000 – http://www.sp2000.org , China Species Information Service (CSIS) – http://www.chinabiodiversity.com , Wildfinder – http://www.worldwildlife.org), until further evidence suggests that it may function at a higher risk level than suggested, this species will be termed Low Risk.

[41] Banksia tricuspis location and total range in Western Australia

Conclusion and recommendations:

As mentioned in the introduction, the Expert system used was found to be rigid and difficult to gauge when faced with “flexible” information regarding fire-return times, plant juvenile periods

13 and even rainfall values. Although rainfall values do fluctuate annually depending on a wide range of factors, the Expert system does not make provision for a flexible model which can incorporate invasive trends which must be so affected by fluctuating ecological parameters. If historical climatological information is accepted as the information base for setting the rules regarding invasiveness and rainfall totals, how often must these be updated?

Additional problems include the request of the system for concise answers to questions where there are in fact a series of correct answers which used could service different outcomes of suggested invasiveness.

Information given by the system as resolution, is only as accurate and as good as the current information fed into the system, and, depending on the individual user, it is felt that a more conservative or less conservative outcome can be manipulated from such a system depending on the interpretation of the questions set out for the rules.

With this in mind, if the Expert system is to be used where land development is indicated, or, where status of riparian land is sought prior to the sale of the property for example, under our current laws, a biased invasive species impact assessment and report can easily be produced under these conditions.

Since an Expert system is primarily an information tool and a profiling system, the information supplied to the system must be up-to-date, and from a single source data-base, which is itself screened for ambiguous data.

Confounding by biological processes may also influence the Expert system on a localised level, where there may be the interaction of a specific biological process in one area which is not accounted for in the base-line data.

It is my personal finding that Expert systems, though in theory, looks as though it should function without many problems, needs to be refined, where rules take on more flexibility and questions to determine rule selection should include more specifics about biological interactions and ecological interactions of similarity without making general assumptions that if given similar conditions, plants in a new area can become invasive. Important factors to include should be the type of and efficiency of predation of not only the seeds in the new environment, but also the flowers, which are the sexual aspects of the plants, and, hybridisation with related indigenous species needs to be taken into account.

Fire-regimes in the long-term may have a negative impact on certain indigenous plant species, whose populations can dwindle as recruitment is diminished by non-fluctuating and strict repetitions of controlled burning, instead of a more natural process of varying time between burns, allowing for periods of recruitment and positive seed-bank building. Conservationists are quick to point out fire-regimes as measures of control for invasive species, but at what cost to indigenous flora and indigenous flora recruitment and seed-bank development and restoration?

Seed banks need to be viewed as investments of genetic material, which can and should fluctuate during periods of heavy and low demand to function the renewal of a species as required by natural processes. In times of advantageous growth and reproduction of plant species, higher numbers of viable seeds will be invested into the seed bank for periods of disadvantage. If we remove this fluctuation, we alter the response of the plants to an ever- changing environment, be it climatic or physical.

David Vaughan

References:

[1] Pacific Island Ecosystems at Risk: http://www.hear.org/pier/species/acacia_longifolia.htm Accessed 26/5/06, 20:44.

14 [2] Encyclopedia of Stanford trees, shrubs and vines: http://trees.stanford.edu/ENCYC/ACAlong.htm Accessed 26/5/06, 20:56.

[3] McMahon A. R. G., Carr G. W., Bedggood S. E., Hill R. J., & Pritchard A. M. 1994 Prescribed Fire and Control of Coast Wattle (Acacia sophorae (Labill.) R.Br.) Invasion in Coastal Heath, South West Victoria. Fire and Biodiversity Conference proceedings 8 – 9 October.

[4] Lister, P. R., Holford P., Haigh T., & Morrison D. A. 1996. Acacia in Australia: Enthobotany and Potential Food Crop. Progress in new crops: In: J. Janick (Editor). ASHS Press, Alexandria, VA, p. 228 – 236.

[5] (Editors) Desanker, P. V., Frost, P. G. H., Justice, C. O., & Scholes, R. J. 1995. The International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme, Report no.41, p. 1 – 106.

[6] Watson, P. & Wardell-Johnston, G. 2004. Fire frequency and time-since-fire effects on the open-forest and woodland flora of Girraween National Park, South-East Queensland, Australia. Austral Ecology 29 (2): p. 225.

[7] Lafay, B. & Burdon, J. J. 2001. Small-Subunit rRNA Genotyping of Rhizobia Nodulating Australian Acacia spp. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 67 (1): p. 396 – 402.

[8] Booderee National Park. Australian Government Department of the Environment and Heritage website: http://www.google.co.za/search? hl=en&q=Acacia+longifolia+native+biota+type&btnG=Search&meta= accessed 13/5/06, 16:44.

[9] Nature Conservation Society of SA 2002. Inquiry into the regulation, control and management of invasive species and the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Amendment (Invasive species) Bill: http://www.aph.gov.au accessed 13/5/06, 16:58.

[10] Blaney, C. S. & Kotanen, P. M. 2001. Post-dispersal losses to seed predators: an experimental comparison of native and exotic old field plants. Canadian Journal of Botany 79 (3): 284 – 292.

[11] Mack R. N., Simberloff D., Lonsdale W. M., Evans H., Clout M., & Bazzaz F. A. 2000. Biotic Invasions: Causes, Epidemiology, Global Consequances, And Control. Ecological Applications 10 (3): 689 – 710.

[12] McCarthy G., Tolhurst K., Bell T., diStefano J., & York A. (date unknown) Forest Ecology – Fire Research. Forest Science Centre, Melbourne University, Australia: http://www.parkweb.vic.gov.au/resources/14_0978.pdf accessed 4/7/06, 23:12.

[13] Duke A. J., 1983. Handbook of Energy Crops (unpublished): http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/duke_energy/Acacia_cyclops.html accessed 23/6/06, 22:26

[14] Wikipedia contributors. Acacia Cyclops. http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php? title=Acacia_cyclops&oldid=45213394. accessed 5/7/06, 19:59

[15] Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, Working for Water Programme. Invasive species. http://www/dwaf.gov.za/wfw/Species/Defaults.asp accessed 5/7/06, 20:35

[16] The Unforgettable Acacias. Modified from: Armstrong W. P. 1998, Zoonooz 71 (8): p. 28 - 31 http://waynesword.palomar.edu/plaug99.htm Accessed 8/7/06: 13:00.

[17] Plant guide. Acacia cyclops. http://www.asla- sandiego.org/content/Download/PlantGuide/Acacia%20cyclops.pdf. Accessed 8/7/06: 13:56.

15 [18] Moore J. 2006. New Biological Agent Curtails Rooikrans. Village Life 17: p. 38 – 39.

[19] Fire in the Kimberley and Inland regions of Western Australia, issues paper October 2005:http://www.epa.wa.gov.au/docs/2129_KimberleyFireRegion_Oct05.pdf Accessed 8/7/06: 15:22.

[20] Turnbull J. W. (no date given) The Australian Environment: Australian Vegetation. http://www.aciar.gov.au/web.nsf/att/JFRN-6BN987/$file/mn24chapter2.pdf Accessed 8/7/06 15:46.

[21] Grierson P. F. & Adamas M. A. 1999. Nutrient cycling and growth in forest ecosystems of South Western Australia. Agroforestry Systems 45: p. 215-244.

[22] Maslin B. R. & McDonald M. W. 2004. Evaluation of Acacia as a woody crop option for Southern Australia. Acacia Search: Joint Venture Agroforestry Program, An Australian Government Initiative. http://www.rirdc.gov.au/reports/AFT/03-017.pdf Accessed 8/7/06: 16:08.

[23] Overheu, T. 2001. Resource Management Technical Report no. 234. http://72.14.209.104/search? q=cache:TJKX0fRlj9MJ:www.agric.wa.gov.au/pls/portal30/docs/folder/ikmp/LWE/RPM/CATM AN/tr234.pdf+Habitat+specialisation+of+Acacia+cyclops&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=7 Accessed 8/7/06: 16:18.

[24] Elser K. & Boucher C. (no date given) The potential impact of invasive woody spp. and their control on alien seed banks, W. Cape, SA. http://www.cc.uoa.gr/biology/medecos/presentations/Thursday/4s/Esler.pdf.

[25] Botany at UWC.ac.za: Getting to know fynbos: http://www.botany.uwc.ac.za/presents/fynbos/65.htm Accessed 9/7/06: 13:59.

[26] Artemisia californica search: http://www.laspilitas.com/plants/93.htm Accessed 9/7/06: 14:19.

[27] Coastal sagebush search: http://www.cnr.vt.edu/dendro/dendrology/syllabus2/factsheet.cfm?ID=769 Accessed 9/7/06: 14:21. [28] Wikipedia contributors. Achene [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; 2006 Jun 22, 14:02 UTC [cited 2006 Jul 9]. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php? title=Achene&oldid=59997430.

[29] Botanical and Ecological characteristics of Atremisia californica: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/shrub/artcal/botanical_and_ecological_characteristic s.html Accessed: 9/7/06: 14:47.

[30] Fire ecology: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/queagr/fire_ecology.html Accessed: 9/7/06: 15:03.

[31] Artemisia californica search: http://www.fs.fed.us/global/iitf/pdf/shrubs/Artemisia %20californica.pdf Accessed: 9/7/06: 15:40.

[32] Natural Resources Conservation Service, Plants profile: Artemisia californica: http://plants.usda.gov/java/profile?symbol=ARCA11 Accessed 9/7/06: 17:02.

[33] California recommended native plant species list: http://www.wildflower2.org/NPIN/Clearinghouse/Factpacks/California/CA_Plants.PDF.

16 [34] Wikipedia contributors, Banksia scabrella [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; Accessed 9/7/06: 17:05. 2006 Jun 30, 01:18 UTC [cited 2006 Jul 9]. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Banksia_scabrella&oldid=61297339.

[35] FloraBase, The Western Australian Flora: http://florabase.calm.wa.gov.au/browse/flora? f=090&level=s&id=1846. Accessed: 9/7/06: 20:31

[36] Chant A., Stack G., & English V. 2005. Irwin’s Conostylis (Conostylis Dielsii Subsp. Teres.) Interim Recovery Plan 2005 – 2009: http://eriss.erin.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/publications/recovery/c-dielsii/pubs/c-dielsii.pdf Accessed 9/7/06: 21:01.

[37] Wikipedia contributors. Banksia [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; 2006 Jul 6, 04:59 UTC [cited 2006 Jul 9]. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php? title=Banksia&oldid+62315630

[38] Forestry Images: http://www.forestryimages.org/browse/detail.cfm?imgnum=1393112 Accessed 10/7/06: 18:33.

[39] Banksia tricuspis image: http://www.anbg.gov.au/images/photo_cd/630930713427/003.html Accessed 10/7/06: 18:56.

[40] Wikipedia Contributors. Banksia tricuspis [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; 2006 Jun 30, 01:21 UTC [cited 2006 Jul 10]. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Banksia_tricuspis&oldid=61297640

[41] FloraBase, The Western Australian Flora: http://florabase.calm.wa.gov.au/browse/flora? f=090&level=s&id=1853 . Accessed: 10/7/06: 19:06

[42] Wikipedia Contributors. Expert system [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia; 2006 Jul 10, 08:45 UTC [cited 2006 Jul 10]. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Expert_system&oldid=63015311

17