Medication Safety in High-Risk Situations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classification of Medicinal Drugs and Driving: Co-Ordination and Synthesis Report

Project No. TREN-05-FP6TR-S07.61320-518404-DRUID DRUID Driving under the Influence of Drugs, Alcohol and Medicines Integrated Project 1.6. Sustainable Development, Global Change and Ecosystem 1.6.2: Sustainable Surface Transport 6th Framework Programme Deliverable 4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Due date of deliverable: 21.07.2011 Actual submission date: 21.07.2011 Revision date: 21.07.2011 Start date of project: 15.10.2006 Duration: 48 months Organisation name of lead contractor for this deliverable: UVA Revision 0.0 Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Programme (2002-2006) Dissemination Level PU Public PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission x Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) DRUID 6th Framework Programme Deliverable D.4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Page 1 of 243 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Authors Trinidad Gómez-Talegón, Inmaculada Fierro, M. Carmen Del Río, F. Javier Álvarez (UVa, University of Valladolid, Spain) Partners - Silvia Ravera, Susana Monteiro, Han de Gier (RUGPha, University of Groningen, the Netherlands) - Gertrude Van der Linden, Sara-Ann Legrand, Kristof Pil, Alain Verstraete (UGent, Ghent University, Belgium) - Michel Mallaret, Charles Mercier-Guyon, Isabelle Mercier-Guyon (UGren, University of Grenoble, Centre Regional de Pharmacovigilance, France) - Katerina Touliou (CERT-HIT, Centre for Research and Technology Hellas, Greece) - Michael Hei βing (BASt, Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen, Germany). -

Postoperative Pain

LONDON, SATURDAY 19 AUGUST 1978 MEDICAL Br Med J: first published as 10.1136/bmj.2.6136.517 on 19 August 1978. Downloaded from JOURNAL Postoperative pain It is an indictment of modern medicine that an apparently carries marginally less risk of depressing respiration or of simple problem such as the reliable relief of postoperative inducing nausea or vomiting. Nevertheless, it does produce pain remains largely unsolved. Numerous patients will bear psychotomimetic side effects, which are related to the dose. testimony to our shortcomings: indeed, after talking to their These reduce its value in the prolonged treatment of very friends, many will expect pain after their operation. At whose severe pain. door can we lay the responsibility-the patients, the doctors, Meptazinol is a new opiate antagonist which produces the nurses, or the pharmaceutical industry ? postoperative analgesia similar to that obtained with pethidine The patients themselves must take a fair share of the and pentazocine.4 Its potency, milligram for milligram, is blame. In no symptom are they more inconsistent and un- similar to pethidine's but its action and sedative effect are reliable. After identical operations under identical anaesthetics somewhat shorter. Cardiovascular performance is not reduced carried out by the same specialists, two patients in the same and respiration is thought to be less affected than with ward may apparently experience entirely different degrees pethidine. The main potential advantage, however, is that in of pain. Personality differences may account for some of the animal studies it has shown a low dependence potential.5 If variations, but we certainly do not understand these well these non-addictive properties are confirmed in man and enough confidently to provide each individual with exactly further clinical trials show no psychotomimetic side effects, http://www.bmj.com/ what he or she needs. -

Veterinary Anesthetic and Analgesic Formulary 3Rd Edition, Version G

Veterinary Anesthetic and Analgesic Formulary 3rd Edition, Version G I. Introduction and Use of the UC‐Denver Veterinary Formulary II. Anesthetic and Analgesic Considerations III. Species Specific Veterinary Formulary 1. Mouse 2. Rat 3. Neonatal Rodent 4. Guinea Pig 5. Chinchilla 6. Gerbil 7. Rabbit 8. Dog 9. Pig 10. Sheep 11. Non‐Pharmaceutical Grade Anesthetics IV. References I. Introduction and Use of the UC‐Denver Formulary Basic Definitions: Anesthesia: central nervous system depression that provides amnesia, unconsciousness and immobility in response to a painful stimulation. Drugs that produce anesthesia may or may not provide analgesia (1, 2). Analgesia: The absence of pain in response to stimulation that would normally be painful. An analgesic drug can provide analgesia by acting at the level of the central nervous system or at the site of inflammation to diminish or block pain signals (1, 2). Sedation: A state of mental calmness, decreased response to environmental stimuli, and muscle relaxation. This state is characterized by suppression of spontaneous movement with maintenance of spinal reflexes (1). Animal anesthesia and analgesia are crucial components of an animal use protocol. This document is provided to aid in the design of an anesthetic and analgesic plan to prevent animal pain whenever possible. However, this document should not be perceived to replace consultation with the university’s veterinary staff. As required by law, the veterinary staff should be consulted to assist in the planning of procedures where anesthetics and analgesics will be used to avoid or minimize discomfort, distress and pain in animals (3, 4). Prior to administration, all use of anesthetics and analgesic are to be approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). -

Opioid Analgesics and the Gastrointestinal Tract

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #64 Carol Rees Parrish, R.D., M.S., Series Editor Opioid Analgesics and the Gastrointestinal Tract Lingtak-Neander Chan Opioids have been used to manage pain and other ailments for centuries. The consti- pating effects of opioid analgesic agents are well known and can be used to manage severe diarrhea and control high output ostomies. Loperamide, diphenoxylate, and difenoxin are currently the only opioid-derivatives approved by the FDA for treating diarrhea. Drug-drug interactions and end organ dysfunction may exacerbate systemic side effects of these drugs. In patients who have failed to respond to these agents, other systemic opioids may be considered. The goal of therapy to control gastrointestinal secretion should be to use the lowest effective dose with minimal side effects. Careful monitoring for systemic side effects during the initiation and dose titration phase are crucial to minimize the risks associated wtih opioid use. INTRODUCTION Sumerian clay tablets inscribed in Cuneiform script he term “opioid” refers to a large group of com- about 3000 B.C. Opium was probably used as an pounds and chemicals that share the characteris- euphoriant in religious rituals by the Sumerians (1,2). Ttics of opium. Opium, from the Greek word During the Middle Ages, after opium was introduced “opos” for juice, refers to the liquid collected from the to Asia and Europe, more extensive documentation of unripe seed capsule of Papaver somniferum L., also opium use became available. It wasn’t until 1805, that known as opium poppy. Opium has been used for med- a young German apothecary named Friedrich Wilhelm icinal purposes for centuries. -

In Collaboration with the World Health Organization

in collaboration with the World Health Organization DELIVER DELIVER, a five-year worldwide technical assistance support contract, is funded by the Commodities Security and Logistics Division (CSL) of the Office of Population and Reproductive Health of the Bureau for Global Health (GH) of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Implemented by John Snow, Inc. (JSI), (contract no. HRN-C-00-00-00010-00), and subcontractors (Manoff Group; Program for Appropriate Technology in Health [PATH]; Social Sectors Development Strategies, Inc.; Synaxis, Inc.; Boston University Center for International Health; Crown Agents Consultancy, Inc.; Harvard University Health Systems Group; and Social Sectors Development Strategies), DELIVER strengthens the supply chains of health and family planning programs in developing countries to ensure the availability of critical health products for customers. DELIVER also provides technical support to USAID’s central contraceptive procurement and management, and analysis of USAID’s central commodity management information system (NEWVERN). This document does not necessarily represent the views or opinions of USAID or the World Health Organization. It may be reproduced if credit is given to John Snow, Inc./DELIVER. Recommended Citation John Snow, Inc./DELIVER in collaboration with the World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Storage of Essential Medicines and Other Health Commodities. 2003. Arlington, Va.: John Snow, Inc./DELIVER, for the U.S. Agency for International Development. Abstract Maintaining proper storage conditions for health commodities is vital to ensuring their quality. Product expiration dates are based on ideal storage conditions and protecting product quality until their expiration date is important for serving customers and conserving resources. Guidelines for the Storage of Essential Medicines and Other Health Commodities is a practical reference for those managing or involved in setting up a storeroom or warehouse. -

A Case of Codeine Induced Anaphylaxis Via Oral Route Hye-Soo Yoo, Eun-Mi Yang, Mi-Ae Kim, Sun-Hyuk Hwang, Yoo-Seob Shin, Young-Min Ye, Dong-Ho Nahm, Hae-Sim Park*

Case Report Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2014 January;6(1):95-97. http://dx.doi.org/10.4168/aair.2014.6.1.95 pISSN 2092-7355 • eISSN 2092-7363 A Case of Codeine Induced Anaphylaxis via Oral Route Hye-Soo Yoo, Eun-Mi Yang, Mi-Ae Kim, Sun-Hyuk Hwang, Yoo-Seob Shin, Young-Min Ye, Dong-Ho Nahm, Hae-Sim Park* Department of Allergy & Clinical Immunology, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, Korea This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Codeine is widely prescribed in clinical settings for the relief of pain and non-productive coughs. Common adverse drug reactions to codeine include constipation, euphoria, nausea, and drowsiness. However, there have been few reports of serious adverse reactions after codeine ingestion in adults. Here, we present a case of severe anaphylaxis after oral ingestion of a therapeutic dose of codeine. A 30-year-old Korean woman complained of the sudden onset of dyspnea, urticaria, chest tightness, and dizziness 10 minutes after taking a 10-mg dose of codeine to treat a chronic cough follow- ing a viral infection. She had previously experienced episodes of asthma exacerbation following upper respiratory infections, and had non-atopic rhi- nitis and a food allergy to seafood. A skin prick test showed a positive response to 1-10 mg/mL of codeine extract, with a mean wheal size of 3.5 mm, while negative results were obtained in 3 healthy adult controls. -

OPIUM Latest Revision: June 30, 2000

OPIUM Latest Revision: June 30, 2000 1. SYNONYMS CFR: Opium CAS #: Codeine Base: 76-57-3 Codeine Hydrochloride: 1422-07-7 Morphine Base: 57-27-2 Morphine Hydrochloride: 52-26-6 Thebaine Base: 115-37-7 Noscapine Base: 128-62-1 Noscapine Hydrochloride: 912-60-7 Papaverine Base: 58-74-2 Papaverine Hydrochloride: 61-25-6 Other Names: Oil poppy Opium poppy 2. CHEMICAL AND PHYSICAL DATA The immediate precursor of heroin is morphine, and morphine is obtained from opium. Opium is the dried milky juice (latex) obtained from the unripe seed pods of Papaver somniferum L., more commonly referred to as the opium poppy or oil poppy. Morphine has also been reported to be present in Papaver setigerum, and as a minor alkaloid in Papaver decaisnei and Papaver rhoeas. However, there is no known instance of these poppies being used for opium production, and work that is more recent has cast considerable doubt as to the presence of morphine in Papaver rhoeas. A major review by Kapoor on the botany and chemistry of the opium poppy is recommended additional reading. Opium latex is obtained from the seed capsule of the poppy while the capsule is still in the green stage, usually seven or more days after flowering and petal fall. Physically, the opium latex is contained within laticiferous vessels, which lie just beneath the epicarp of the seed capsule. The latex is harvested by making a series of shallow incisions through the epicarp, which allows the latex to "bleed" onto the surface of the seed capsule. Most commonly, the latex is allowed to partially dry on the capsule surface, and is then removed by scraping the capsule with specially designed hand tools. -

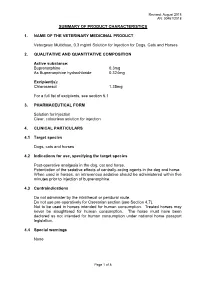

Summary of Product Characteristics

Revised: August 2018 AN: 00451/2018 SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1. NAME OF THE VETERINARY MEDICINAL PRODUCT Vetergesic Multidose, 0.3 mg/ml Solution for Injection for Dogs, Cats and Horses 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Active substance: Buprenorphine 0.3mg As Buprenorphine hydrochloride 0.324mg Excipient(s): Chlorocresol 1.35mg For a full list of excipients, see section 6.1 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Solution for injection Clear, colourless solution for injection 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Target species Dogs, cats and horses 4.2 Indications for use, specifying the target species Post-operative analgesia in the dog, cat and horse. Potentiation of the sedative effects of centrally-acting agents in the dog and horse. When used in horses, an intravenous sedative should be administered within five minutes prior to injection of buprenorphine. 4.3 Contraindications Do not administer by the intrathecal or peridural route. Do not use pre-operatively for Caesarian section (see Section 4.7). Not to be used in horses intended for human consumption. Treated horses may never be slaughtered for human consumption. The horse must have been declared as not intended for human consumption under national horse passport legislation. 4.4 Special warnings None Page 1 of 8 Revised: August 2018 AN: 00451/2018 4.5 Special precautions for use i) Special precautions for use in animals Buprenorphine may cause respiratory depression and as with other opioid drugs, care should be taken when treating animals with impaired respiratory function or animals that are receiving drugs that can cause respiratory depression. In case of renal, cardiac or hepatic dysfunction or shock, there may be greater risk associated with the use of the product. -

Acute Toxic Effects of Club Drugs

Club drugs p. 1 © Journal of Psychoactive Drugs Vol. 36 (1), September 2004, 303-313 Acute Toxic Effects of Club Drugs Robert S. Gable, J.D., Ph.D.* Abstract—This paper summarizes the short-term physiological toxicity and the adverse behavioral effects of four substances (GHB, ketamine, MDMA, Rohypnol®)) that have been used at late-night dance clubs. The two primary data sources were case studies of human fatalities and experimental studies with laboratory animals. A “safety ratio” was calculated for each substance based on its estimated lethal dose and its customary recreational dose. GHB (gamma-hydroxybutyrate) appears to be the most physiologically toxic; Rohypnol® (flunitrazepam) appears to be the least physiologically toxic. The single most risk-producing behavior of club drug users is combining psychoactive substances, usually involving alcohol. Hazardous drug-use sequelae such as accidents, aggressive behavior, and addiction were not factored into the safety ratio estimates. *Professor of Psychology, School of Behavioral and Organizational Sciences, Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, CA. Please address correspondence to Robert Gable, 2738 Fulton Street, Berkeley, CA 94705, or to [email protected]. Club drugs p. 2 In 1999, the National Institute on Drug Abuse launched its Club Drug Initiative in order to respond to dramatic increases in the use of GHB, ketamine, MDMA, and Rohypnol® (flunitrazepam). The initiative involved a media campaign and a 40% increase (to $54 million) for club drug research (Zickler, 2000). In February 2000, the Drug Enforcement Administration, in response to a Congressional mandate (Public Law 106-172), established a special Dangerous Drugs Unit to assess the abuse of and trafficking in designer and club drugs associated with sexual assault (DEA 2000). -

WO 2014/006004 Al 9 January 2014 (09.01.2014) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2014/006004 Al 9 January 2014 (09.01.2014) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 9/20 (2006.01) A61K 31/485 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/EP2013/06385 1 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 1 July 20 13 (01 .07.2013) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (25) Filing Language: English OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SC, (26) Publication Language: English SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: PA 2012 70405 6 July 2012 (06.07.2012) DK (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 61/668,741 6 July 2012 (06.07.2012) US kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, (71) Applicant: EGALET LTD. -

List of Narcotic Drugs Under International Control

International Narcotics Control Board YYeellllooww LLiisstt Annex to Forms A, B and C 50th edition, December 2011 LIST OF NARCOTIC DRUGS UNDER INTERNATIONAL CONTROL Prepared by the INTERNATIONAL NARCOTICS CONTROL BOARD* Vienna International Centre P.O. Box 500 A-1400 Vienna, Austria Internet address: http://www.incb.org/ in accordance with the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961** Protocol of 25 March 1972 amending the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961 ___________ * On 2 March 1968, this organ took over the functions of the Permanent Central Narcotics Board and the Drug Supervisory Body, retaining the same secretariat and offices. ** Subsequently referred to as “1961 Convention”. Purpose The Yellow List contains the current list of narcotic drugs under international control and additional relevant information. It has been prepared by the International Narcotics Control Board to assist Governments in completing the annual statistical reports on narcotic drugs (Form C), the quarterly statistics of imports and exports of narcotic drugs (Form A) and the estimates of annual requirements for narcotic drugs (Form B) as well as related questionnaires. The Yellow List is divided into four parts: Part 1 provides a list of narcotic drugs under international control in form of tables and is subdivided into three sections: (1) the first section includes the narcotic drugs listed in Schedule I of the 1961 Convention and/or Group I of the 1931 Convention; (2) the second section includes the narcotic drugs listed in Schedule II of the 1961 Convention and/or Group II of the 1931 Convention; and (3) the third section includes the narcotic drugs listed in Schedule IV of the 1961 Convention and/or Group II of the 1931 Convention. -

Division of Vital Statistics, Mortality Data Table Page 1 of 147

Division of Vital Statistics, Mortality Data Table page 1 of 147 Table I–1. Search terms to identify drugs mentioned in electronic death certificate literal text and associated principal variant, Version 06-30-2015 Spreadsheet version available from: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Publications/NVSR/65_09/Table01.xlsx. Search term Principal variant A PRAZOLAM ALPRAZOLAM ABACAVIR ABACAVIR ABARELIX ABARELIX ABATACEPT ABATACEPT ABCIXIMAB ABCIXIMAB ABILIFY ARIPIPRAZOLE ABIRATERONE ABIRATERONE ABOBOTULINUMTOXINA ABOBOTULINUMTOXINA ABSTRAL FENTANYL ACAMPROSATE ACAMPROSATE ACARBOSE ACARBOSE ACDETAMINOPHEN ACETAMINOPHEN ACEBUTOLOL ACEBUTOLOL ACEPROMAZINE ACEPROMAZINE ACETAMINOP ACETAMINOPHEN ACETAMINOPHEN ACETAMINOPHEN ACETAZOLAMIDE ACETAZOLAMIDE ACETIC ACID ACETIC ACID ACETOHEXAMIDE ACETOHEXAMIDE ACETOHYDROXAMIC ACID ACETOHYDROXAMIC ACID ACETOMINOPHEN ACETAMINOPHEN ACETONE ACETONE ACETOPHENAZINE ACETOPHENAZINE ACETYL MORPHINE HEROIN ACETYLCARBROMAL ACETYLCARBROMAL ACETYLCHOLINE ACETYLCHOLINE ACETYLCYSTEINE ACETYLCYSTEINE ACETYLSALICYCLIC ACID ACETYLSALICYLIC ACID ACETYLSALICYLACID ACETYLSALICYLIC ACID ACETYLSALICYLIC ACID ACETYLSALICYLIC ACID ACETYSALICYLIC ACID ACETYLSALICYLIC ACID ACITRETIN ACITRETIN ACRIFLAVINE ACRIFLAVINE ACRIVASTINE ACRIVASTINE ACTIQ FENTANYL ACYCLOVIR ACYCLOVIR ADALIMUMAB ADALIMUMAB ADANON METHADONE ADAPALENE ADAPALENE ADDERALL AMPHETAMINE DEXTROAMPHETAMINE ADEFOVIR ADEFOVIR AFATINIB AFATINIB U.S. Department of Health and Human Services · Centers for Disease Control and Prevention · National Center for Health