David Sum’s Crim Law Summary, Professor Klein, Summer 2015 Drop me a line if this has been helpful!

Table of Contents

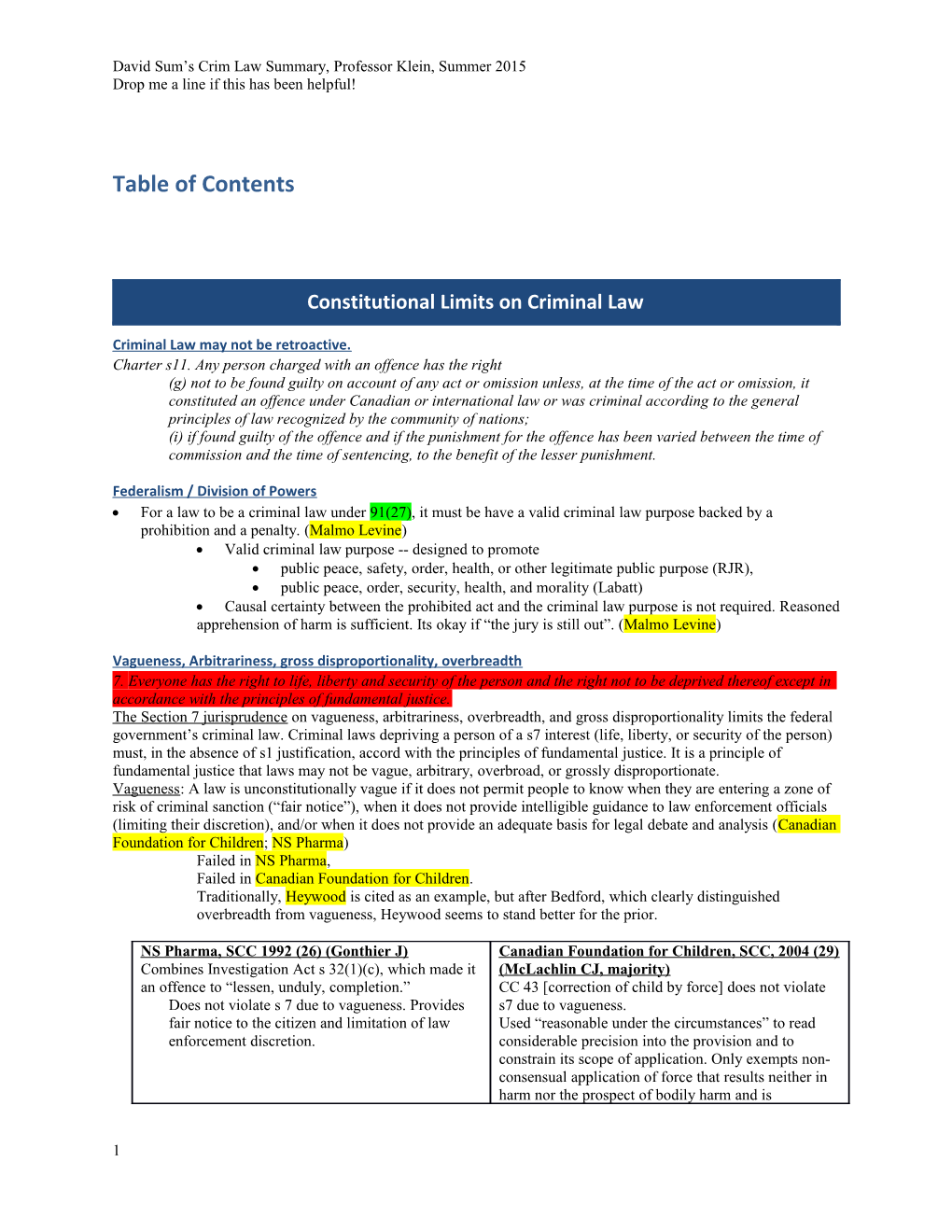

Constitutional Limits on Criminal Law

Criminal Law may not be retroactive. Charter s11. Any person charged with an offence has the right (g) not to be found guilty on account of any act or omission unless, at the time of the act or omission, it constituted an offence under Canadian or international law or was criminal according to the general principles of law recognized by the community of nations; (i) if found guilty of the offence and if the punishment for the offence has been varied between the time of commission and the time of sentencing, to the benefit of the lesser punishment.

Federalism / Division of Powers For a law to be a criminal law under 91(27), it must be have a valid criminal law purpose backed by a prohibition and a penalty. (Malmo Levine) Valid criminal law purpose -- designed to promote public peace, safety, order, health, or other legitimate public purpose (RJR), public peace, order, security, health, and morality (Labatt) Causal certainty between the prohibited act and the criminal law purpose is not required. Reasoned apprehension of harm is sufficient. Its okay if “the jury is still out”. (Malmo Levine)

Vagueness, Arbitrariness, gross disproportionality, overbreadth 7. Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice. The Section 7 jurisprudence on vagueness, arbitrariness, overbreadth, and gross disproportionality limits the federal government’s criminal law. Criminal laws depriving a person of a s7 interest (life, liberty, or security of the person) must, in the absence of s1 justification, accord with the principles of fundamental justice. It is a principle of fundamental justice that laws may not be vague, arbitrary, overbroad, or grossly disproportionate. Vagueness: A law is unconstitutionally vague if it does not permit people to know when they are entering a zone of risk of criminal sanction (“fair notice”), when it does not provide intelligible guidance to law enforcement officials (limiting their discretion), and/or when it does not provide an adequate basis for legal debate and analysis (Canadian Foundation for Children; NS Pharma) Failed in NS Pharma, Failed in Canadian Foundation for Children. Traditionally, Heywood is cited as an example, but after Bedford, which clearly distinguished overbreadth from vagueness, Heywood seems to stand better for the prior.

NS Pharma, SCC 1992 (26) (Gonthier J) Canadian Foundation for Children, SCC, 2004 (29) Combines Investigation Act s 32(1)(c), which made it (McLachlin CJ, majority) an offence to “lessen, unduly, completion.” CC 43 [correction of child by force] does not violate Does not violate s 7 due to vagueness. Provides s7 due to vagueness. fair notice to the citizen and limitation of law Used “reasonable under the circumstances” to read enforcement discretion. considerable precision into the provision and to constrain its scope of application. Only exempts non- consensual application of force that results neither in harm nor the prospect of bodily harm and is

1 corrective; does not apply for children under 2 or teenagers, corporeal punishment by teachers, use of implements, etc. Arbour, dissenting: CC 43 is unconstitutionally vague; it does not delineate a clear risk zone. Majority’s reading down of the provision is contrary to CC 9.

Arbitrariness: A law is arbitrary when there is no rational connection between its object and effects. (Bedford) E.g. Morgentaler: Provision required therapeutic abortion committee approval. Purpose was to protect women’s health. Provision did nothing protect women’s health and, in fact caused delays. E.g. PHS: Drug possession laws precluded operation of safe injection centre. Objective of possession laws was protection of health and safety. Safe injection centre in fact advanced this objective. Overbreadth: a law is overbroad if it interferes with some conduct that bears no connection to its objective – overbreadth involves arbitrariness in part (Bedford). E.g. Bedford: the “living on the avails provisions” (CC 212, prior to C-36) were overbroad because while their purpose was to protect prostitutes from exploitation, they captured not only exploitive conduct (of, for example, pimps), but also non-exploitive conduct (of, for example, drivers, bodyguards, etc.) that in fact protected prostitutes. E.g. R v Heywood: provision prohibited offenders convicted of certain offences from “loitering” in public parks. Purpose: to protect children from sexual predators. Overbroad b/c applied to offenders who did not constitute a danger to children, and to parks were children were unlikely to be present. Gross disproportionality: A law is grossly disproportionate if it the deprivation of s7 interests it causes is “totally out of sync” with the objective of the measure (Bedford). E.g. Bedford: the bawdy house and communication prohibition provisions (CC 197, 210, 212(1)(j), 213(1)(c), all prior to C-36) were grossly disproportionate. Their purpose was to forbid prostitution as a nuisance; to prevent harm to communities where prostitution was carried out in a notorious or habitual manner. Their effect was to place prostitutes lives and security at risk by pushing them towards more dangerous forms of prostitution (e.g. “out-calls) and by preventing them from screening their clients. E.g. a measure with the purpose of keeping streets clean is grossly disproportionate if it imposes life imprisonment for spitting on the sidewalk. E.g. PHS: Minister’s refusal to exempt the safe injection site from drug possession laws because the effect of denying health services and increasing the risk of death and disease of drug users was grossly disproportionate to the objectives of the drug possession laws, namely public health and safety. A determined Parliament can, by explicitly defining its objectives broadly, mitigate the degree to which s7 constrains its ability to adopt criminal law. This occurred, for example, with Bill C-36, which re-enacted provisions functionally similar to the ones that the SCC struck down in Bedford. C-36 makes clear its purpose is not merely to protect prostitutes from exploitation or address the nuisances of prostitution, but rather to prevent the exploitation, objectification, and other social harm that is “inherent” in prostitution. It is unclear if this more broadly framed purpose would address overbreadth by covering effects that appeared unrelated to the narrower legislative purpose, or would address gross proportionality in light of the revised purpose’s greater importance. This is an example of the courts altering criminal law lately. How might Malmo-Levine be decided today?

Heywood, SCC, 1994 (28) (Cory J, majority) Bedford, SCC, 2013 (per McLachlin) CC 179(1)(b) [vagrancy] found unconstitutional on Three applicants, all current or former prostitutes, the basis of s7 – overbreadth. Vagueness discussed, sought declarations that three provisions of the but seems decided on the basis of overbreadth. Criminal Code are unconstitutional. 179(1)(b): offence for a person with past history of Section 210 (with s197) bawdy-house – struck down sexual violence to be “found loitering in or near a on the basis of gross disproportionality. school ground, playground, public park…” etc. Section 212(1)(j) live on the avails of another’s Too broad in terms of geographical scope, duration, prostitution – overbroad. number of persons it covers, etc. Not necessary to Section 213(1)(c) makes it an offence to either stop or achieve state’s objectives of protecting children from attempt to stop, or communicate or attempt to

2 David Sum’s Crim Law Summary, Professor Klein, Summer 2015 Drop me a line if this has been helpful!

sexual predators. communicate with, someone in a public place for the Gonthier, dissenting: there is no overbreadth. purpose of engaging in prostitution or hiring a Ignorance of the law is no excuse (CC 19). prostitute – gross disproportionality.

Harm principle – not a PFJ… good try.

Malmo Levine , SCC, 2003 () The possession offence in the Narcotics Control Act is constitutional. The accused sought and failed to establish the “harm principle” as a fundamental justice, arguing that it is (where a s7 interest is implicated and there is no justification under s1) unconstitutional to criminalize conduct that does not harm others. Mill’s harm principle: government cannot wield its coercive power to achieve solely moral ends. Rather, it may only act to prevent harm to others. The court devised and applied a test for determining whether something is a principal of fundamental justice. It found that the harm principle is not one, first because there is no societal consensus regarding harm principle (non harmful offences like cannibalism and bestiality are criminalised), and because it would not result in a manageable standard. (people disagree on what qualifies as a harm, as illustrated by this case) Arbour J dissented, extending the “morally innocent should not be punished” principle of fundamental justice (BC Motor Vehicle) to preclude punishment of persons have not harmed another on the basis such persons are morally innocent. Suggested that where harm is alleged to society as a whole, the harm of the prohibited conduct must outweigh harm resulting from enforcement. Which resembles the gross proportionality analysis.

R v Labaye, SCC, 2005 (70) The test for “indecency” in CC 197(1), pre C-36, [definition of bawdy house] is based on the harm principle. Test: Indecent criminal conduct will be established where the crown proves beyond a reasonable doubt: 1. Conduct by its nature causes harm/presents significant risk of harm to individuals or society in a way that undermines/threatens to undermine a value reflected in and endorsed through the Constitution or similar fundamental laws by (non-exhaustive list) a) confronting members of the public with conduct that significantly interferes with their autonomy and liberty b) predisposing others to antisocial behaviour c) physically or psychologically harming persons involved in the conduct Must be careful here not to leap from disgust to assumed psychological harm. Easier to infer w.r.t. vulnerable persons. Bad taste, majority disapproval, moral views do not suffice. Why need to be reflected in law? Make the test objective. 2. The harm or risk of harm is of a degree that is incompatible with the proper functioning of society Threshold is high. We must be prepared to tolerate conduct of which we disapprove. This requires value judgments. Judges must approach the task with awareness of danger of deciding based on unarticulated values and prejudices, must make value judgements on the basis of evidence, must fully articulate them. Application: A swingers club was not indecent because everything was in private, for members only; there was no evidence of anti-social attidues towards women, and the only possible to danger to participants was catching a STD.

The harm principle as a PFJ limits what the legislator can do. The harm principle as an interpretive principle helps explain, where this is unclear, what the legislature did. Legislature could simply have outlawed swinging, instead of outlawing “indecency”. This likely would have survived a challenge

Principle of Legality

3 CC s 8(3), adopted in 1953, allows for the use of all CML defenses, insofar as they are not inconsistent with the CC. It also permits the development and evolution of new defences (Amato). CC s9 abolishes all CML offences. Even before Parliament adopted s9 in 1953, Canadian courts stopped inventing new offences with no precedent in statute or case law (Frey v Fedoruk). S9 explicitly preserves contempt. Thus, criminal contempt remains a offence even though it is not codified (United Nurses of AB) Why? It is impossible to foresee all circumstances which may excuse an offense, and the use of the Code should not risk depriving individuals of a defence.

Amato, SCC, 1982 Frey v Fedoruk, SCC, 1950 Is the D not guilty thanks to the defense of entrapment, Frey was charged with “peeping” after he was caught even though the defense of entrapment is not in the CC looking into a woman’s room in Fedoruk’s house. and was not a defense in 1953 when [now] s 8(3) was Issue: Is “peeping” an offence, even though there is no added? – Can judges develop new CML defenses? [Yes] precedent for it? (no) Offences must be found in the code or in precedent Rationale: need for certainty!

Fair Notice / Principle of Legality This principal of legality, the idea that there must be fair notice of a criminal law a provision… Okay, but courts still interpret. Sometimes in unexpected ways. In ways that seem to cut against fair notice. So has anything changed? S7 of the Charter does not require that (it is not a principle of fundamental justice that) all criminal offenses be codified (United Nurses). No constitutional requirement for codification. Hart Devlin debate Mabior

Interpreting the CC

In the absence of ambiguity, CC provisions should be given a purposive interpretation in accordance with Driedger’s modern approach and s 12 of the Interpretation Act (Bell ExpressVu). Modern Approach: They should be “read in their entire context and in their grammatical and ordinary sense harmoniously with the scheme of the Act, the object of the Act, and the intention of Parliament”. Interpretation Act s 12: every enactment…shall be given…liberal construction and interpretation as best ensures the attainment of its objects. Where ambiguity is present, the doctrine of strict construction will apply: the court should adopt the interpretation most favourable to the accused (R v Pare; Bell ExpressVu). The ambiguity must be “real”. The words of the statute, read in their entire context, must be reasonably capable of more than one meaning, each equally in accordance with the intentions of the statute (Bell ExpressVu).

R v Pare – I’ll put this in the murder section

Burden of Proof Charter 11(d): Any person charged with an offence has a right (d) to be presumed innocent until proven guilty according to law in a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal The presumption of innocence, guaranteed in 11(d) of the Charter, requires the prosecution to prove every aspect of a criminal charge (elements of the offence, collateral factors, excuses, defenses) beyond a reasonable doubt. Any requirement that the accused prove or disprove some fact on the balance of probabilities to avoid conviction violates the presumption of innocence because it permits a conviction in spite of a reasonable doubt (R v Oakes, R v Whyte). An infringement of 11(d) may, of course, be justified under s1 (Keegstra, Wholesale Travel) The elimination of an element of an offence altogether, as in strict liability, does not infringe 11(d), which concerns the burden of proof rather than the nature of the offence (Transport Robert)

R v Oakes, SCC, 1986 (284) (Dickson) R v Keegstra, SCC, 1990 (290) (Dickson)

4 David Sum’s Crim Law Summary, Professor Klein, Summer 2015 Drop me a line if this has been helpful!

Provisions of the Narcotics Control Act infringed 11(d) It infringes 11(d) that the truth defense (CC 319(3)(a)) to because they placed on the accused the burden of the offense of hate speech (CC 319(2)) requires the disproving on the balance of probabilities an essential accused to establish that his statements were true, but element of an offence. this infringement is justifiable under s1, given the An accused would, once convicted of possession, be importance of eradicating hate speech, and the presumed to have been in possession for the purpose of difficulties that would be involved in requiring the trafficking (a more serious offence), unless he succeeded crown to prove that hate speech is false. at rebutting this presumption on the balance of probabilities.

Quantum of Proof “beyond a reasonable doubt” has a special meaning in the criminal law context. A reasonable doubt is not an imaginary or frivolous doubt. (Lifchus) It is based on evidence, reason, and common sense rather than sympathy or prejudice. (Lifchus) “Beyond a reasonable doubt” requires more than the balance of probabilities, but less than absolute certainty, though it lies closer to absolute certainty than the balance of probabilities (R v Starr).

R v Lifchus, SCC, 1997 (292) (Cory J) R v Starr, SCC, 2000 (294) Trial judge erred by telling jury to use the phrase Trial judge instructed the jury that “beyond a “reasonable doubt” in its “ordinary, natural every day reasonable doubt” does not require proof or certainty, sense.” did not otherwise fully explain the concept. SCC explained what “beyond a reasonable doubt” Majority found the trial judge erred. means and provided model jury instructions. Dissent (L’Heureux Dube): found the trial judge’s instructions were suffice. Leifchus is not a iron-clad roster.

Actus reus (culpable act)

Components of the Actus reus 1) physically voluntary 2) act or omission 3) sometimes in certain proscribed circumstances 4) sometimes causing certain consequences.

The actus reus must be “physically” voluntary Conduct is criminal only if it is voluntary; only if the accused was aware of what she was doing could have done otherwise (Ruzic, King, Killbride, contra Larsonner). This is a principal of fundamental justice under s7 (Daviault). Voluntariness is a requirement of the actus reus, separate from the mens rea. It concerns not the accused state of mind, but merely whether the accused had, under the circumstances, free will. Examples: In Killbride, NZ, 1962 (312), the case failed for lack of voluntariness because the accused’s “warrant of fitness” inexplicably disappeared from his car while it was parked downtown. The accused could not be convicted for missing the warrant because he played no part in its disappearance; no other option was open to him. In King, SCC, 1962 (314), the case failed for lack of voluntariness because the accused had not heard his dentist’s warning concerning the effects of the anesthetics administered, and therefore had no way of knowing that, when he began driving, he was driving under the influence.

Criminalizing Omissions CML jurisdictions are generally reluctant to impose positive legal duties. Thus, the starting point is that the criminal law will not punish omissions. There are, however, exceptions to this rule.

5 Specific Omission Offences: CC provisions that impose a duty and then punish for failure to discharge it (e.g. CC 50(1)(b) [omitting to prevent treason], 129(b) [omitting to assist a peace officer], 252(1) [failure to stop at the scene of an accident]). General Omission Offences: CC provisions which impose a penalty for “failure to discharge a duty” but fail to specify the duty. – common nuisance (CC 180) and Criminal negligence (CC 219-21). Here, the relevant duties are: Found in the criminal code 215 [duty to provide necessaries], 216 [duty of care in medical treatment] (Thornton, per SCC), 217.1 [duty of supervisors] 217 [duty to uphold undertakings]: An undertaking for the purposes of s 217 must be in the nature of a commitment, clearly made, and with binding intent. Relationship between the parties is irrelevant. (R v Brown) Because of CML’s general reluctance to impose positive duties, courts will interpret these duties narrowly. Abella’s treatment of 217 in R v Brown illustrates this. Found in statute Including provincial statute, so in Quebec: the duty to rescue (QC Charter art 2). Does this place a criminal law power in provincial hands? Found at CML – this is controversial. “Duty imposed by law” (s 219(2)) and “legal duty” (s 180(2)) are identical in meaning. They both include duties imposed by statute or at CML (Thorton, ONCA – not affirmed by SCC). Effectively criminalizing omissions through the interpretation of CC offences that do not explicitly do so. In Mabior, the court arguably criminalised an omission – the omission of failure to disclose one’s HIV status. Of course, the court characterised what it did as the criminalisation of an action – the criminalisation of fraud, but this is all a matter of perspective.

R v Brown, ONCA, 1997 (319) R v Thornton, ONCA, 1991 (323) R v Mabior, SCC, 2012 FACTS: B’s girlfriend A swallowed FACTS: T knew he was HIV- FACTS: M failed to disclose his a large bag of crack to avoid being positive and lied to donate blood. HIV+ status to 4 partners. arrested. Attempted to induce ISSUE: Did T fail to discharge a ISSUE: Did the failure to disclose vomiting but failed. Several hours legal duty (negligence) such that he vitiate consent by fraud (CC 265(3) later she became sick. B told her he is guilty of common nuisance (CC (b)) such that M is guilty of would take her to the hospital. He 180)? (Yes) aggravated (CC 268) sexual (CC did so, but via taxi instead of via “Legal duty” in CC 180(2) includes 271) assault (CC 265(1))? (yes) ambulance. duties at CML, such as the duty to Currier test: Failure to disclose ISSUE: Did B breach an refrain from conduct which is HIV+ status before having sex undertaking (CC 217) such that he is reasonably foreseeable to cause vitiates consent by fraud where there guilty of criminal negligence (CC serious harm to other persons is: (1) a dishonest act – falsehoods or 219) causing death (CC 220)? (no) (negligence). a failure to disclose; (2) deprivation The evidence does not disclose SCC Consideration: – denying the complainant anything of a binding nature Summarily dismissed the knowledge which would have here, so no undertaking was appeal, but on the basis of a s caused her to refuse sexual relations found. No duty for the purposes 216 duty rather than a CML that exposed her to a significant risk of s 219. Therefore no criminal duty, even though this does not of serious bodily harm. liability. Acquittal. appear to have been raised at Mabior’s clarification: A trial or the ONCA, and even “significant risk of serious bodily though it is an awkward fit harm” means a “significant risk of (seems to be talking about transmission”. It is absent where the doctors). This leaves some accused’s viral load is low and a ambiguity as to whether CML condom is used. It is present where a duties are sufficient for s 180 condom is not used while the viral and s 219. load is low or where a condom is used but the viral load is high.

6 David Sum’s Crim Law Summary, Professor Klein, Summer 2015 Drop me a line if this has been helpful!

Contemporaneity Although the actus reus and mens rea must coincide, they don’t have to be completely concurrent. Where a series of acts form part of the same transaction, it is sufficient if the requisite intent coincides at any time with the an element of the transaction (Cooper) e.g. series of blows with a baseball bat, beating someone then throwing them off a cliff (even if death was after the fact due to exposure), etc. (Cooper) An act that is innocent at the outset can become criminal at a later stage when the accused acquires knowledge of the nature of the act and still refuses to change his course of action (Cooper). The mans rea is effectively “superimposed” on the existing actus reus which is continuing (Fagan). These statements reflect what the HoL in Miller called the “continuing act theory” (Miller) The “duty theory” provides an alternative way to address the problem of contemporaneity: an unintentional act followed by an intentional omission to rectify that act or its consequences can be regarded, as a whole, as an intentional act (Miller). Courts have interpreted contemporaneity loosely, requiring only some overlap between the actus reus and mens rea. Thus, cases seldom fail for lack of contemporaneity (Fagan, Miller, Cooper). In peculiar fact situations however, contemporaneity can cause issues (R v Williams)

Fagan, UKQB, 1969 (302) R v Miller, UK 1982 then UKHoL 1983 (305) FACTS: F accidentally drove onto a police officer’s FACTS: Miller, a squatter, lit a cigarette and fell asleep. foot, temporarily refused to drive off of, finally agreed to When he awoke the room was on fire. He got up and drive off of it and did so. went to another room to continue sleeping. The house ISSUE: Was there contemporaneity such that F is guilty burned down, he was rescued. of assault (now CC 265) (Yes) ISSUE: was there contemporaneity such that M is guilty The mans rea was superimposed onto the actus reus, an of arson (now CC 433 et seq) (yes). existing act that was continuing. The unintentional act followed by an intentional omission to rectify the act amounted to actus reus. R v Cooper, SCC, 1993 (307) R v Williams, SCC, 2003 FACTS: C became angry with the victim, grabbed her FACTS: W had consensual sex with the victim for 5 by the throat with both hands and shook her. The next months, then learned he was HIV+, then continued to thing he remembers is that he was in his car with the have (still apparently consensual) sex with the victim for victim’s dead body beside him. a year. The victim contracted HIV. ISSUE: Did C murder (CC 229(a)(ii) the victim? Was it ISSUE: was there contemporaneity such that W was enough that he formed the intent to cause the victim guilty of aggravated (CC 268(1)) assault (CC 268(1))? bodily harm that he knew was likely to cause her death, (no) even if he was not aware of what he was doing at the Failure to disclose information (such has HIV+ moment she actually died? (Yes) status) that changes the nature and quality of an act vitiates consent (interpretation) For the first 5 months, there was endangerment (actus reus) but no intent (mans rea). For the last 12 months there was intent (mans rea) but it is not clear beyond a reasonable doubt that there was endangerment (actus reus). Thus, there was not contemporaneity.

Causation

Factual Causation Factual causation is established where the prohibited consequence would not have occurred but for the accused’s act (Maybin). There may be other causes. This is irrelevant. (Maybin) Cases seldom fail for lack of factual causation, but one did in R v Winning, ONCA, 1973. The accused submitted a false information on a credit application. She was not guilty of obtaining credit under false

7 pretenses (CC 362(1)(b)) because the credit company only relied on the accused’s name and address, which she had listed correctly. The accused’s provision of false information therefor did not cause her acquisition of the credit.

Legal Causation The standard for legal causation in criminal law is “significant contributing cause” (Smithers, as reformulated in Nette), or “at least a contributing cause, outside the de minimis range” (Smithers). Standard of proof: beyond a reasonable doubt (Smithers) This is a question of fact, to be determined by the finder of fact, in light of the totality of evidence. Intention, foresight, or risk are not relavent to causation. (Smithers) It is irrelevant whether there are other contributing causes (Smithers) Thin skull rule: the criminal must take his victim as he finds him (Smithers) The most trivial assault renders its author guilty of culpable homicide if, through some unforeseen weakness of the victim, it causes death (Smithers; Blaue) In Smithers, the accused was guilty of manslaughter even though the victim would not have died had his epiglottis not malfunctioned. In Blaue, the accused was guilty of manslaughter even though the victim would not have died had she accepted a blood transfusion. The court treated the victim’s religious beliefs (Jahovah’s Witness) as a thin skull rather than an intervening cause. The Smithers standard of causation, when combined with a fault requirement (for manslaughter, objective foreseeability of bodily harm), does not infringe s7. It is a principle of fundamental justice that the morally innocent should not be punished. Causation and fault, together, assure that they are not punished. (Cribbin) The standard of causation to establish 1 st degree murder (CC 231), once murder generally (CC 229) is already established according to the Smithers standard, is higher than the Smithers standard: the accused’s act must have been a substantial and integral cause of the victim’s death (Harbottle). This higher standard applied to 1st degree murder only, it does not apply to 2nd degree (CC 231(7)) murder. It reflects the increased culpability that is associated with particularly intense participation in a murder (Nette). Why did Harbottle arrive at this interpretation? Severity of consequences of a 1st degree murder conviction, 1st degree murder is dealt with after causation for murder has already been dealt with. To require the same standard of causation would be redundant (I find this logic questionable). (Harbottle)

Smithers, SCC, 1978 (339) Cribbin, ONCA, 1994 (344) FACTS: The accused kicked the victim in the stomach, FACTS: The accused beat the victim and left him on the the victim vomited, his epiglottis malfunctioned, he side of the road. His injuries were not life threatening, inhaled his own vomit, and he died. but he drowned in his own blood while unconscious. ISSUE: Did the kick cause the victim’s death (CCC The accused was found guilty of manslaughter (CC 236; 222(5)(a)) such that the accused is guilty of 222). manslaughter (CC 236)? (yes) ISSUE: Is the standard of causation set out in Smithers The kick was a contributing cause of death. constitutional under s7? (yes) The malfunctioning epiglottis was too, but this is Fault element: Manslaughter requires objective irrelevant. foreseeability of bodily harm which is neither trivial nor transitory, arising from a dangerous act (R. v Creighton) This fault element plus the Smithers causation standard assures that, the morally innocent are not punished, which is a PFJ. Harbottle, SCC, 1993 (358) Nette, SCC, 2001 (363) (Arbour) FACTS: H and a companion kidnapped a woman. The FACTS: The accused hogtied the victim, a weak 95- companion assaulted her, then strangled her while H year-old-woman, and tied a ligature around her neck held her legs down. while robbing her house. The woman fell off the bed and ISSUE: What is the standard of causation for 1st degree 24-48 hours later, died. (CC 231) murder (CC 229)? (substantial and integral ISSUE: What is the standard of causation for second- cause) degree (CC 231(7)) murder (CC 229)? (the Smithers H is guilty of first-degree murder on the basis that H “contributing cause” std.)

8 David Sum’s Crim Law Summary, Professor Klein, Summer 2015 Drop me a line if this has been helpful! caused the victim’s death while the forcibly confining The causation standard expressed in Smithers applies to her (CC 231(5))? all forms of homicide. Cause here means “substantial and integral cause” on the The higher standard of causation for the first degree facts, this standard is met. piece of first degree murder (Harbottle) applies only to 1st degree murder, and reflects the increased culpability that is associated with particularly intense participation in a murder. L’Heureux-Dub é, dissenting on the law Disagrees with Arbour’s reformulation of the Smithers test into “significant contributing cause”

Intervening Causes The accused is not guilty where an intervening cause breaks the chain of causation between the act of the accused and the consequence element of the offence such that the accused’s act is not a significant contributing cause of the prohibited consequence (Maybin, Reid & Stratton). The Smithers/Nette “significant contributing cause” test is dispositive in the analysis of whether an intervening act broke the chain of causation, but the “foreseeability” and “intervening act” analyses are helpful interpretive aids. (Maybin) Foreseeability – was the general nature of the intervening act and the risk of harm it connoted objectively foreseeable? It is sufficient if the general nature of the intervening act and risk of non- trivial harm are objectively foreseeable. The details of the intervening event may be be unpredictable and need not be foreseeable. (Maybin) Intervening Act – was the intervening act independent of (rather than directly linked to) the accused’s actions – and did it overwhelm the accused’s actions – such that it became, at law, the sole cause of the victim’s death? (Maybin) Examples of intervening causes that break the chain of causation: X assaults Y, who dies when an earthquake causes the building in which he fell unconscious to collapse. X is not guilty of homicide; the earthquake is an intervening cause. (mentioned in Reid & Stratton) X assaults Y, Z carries Y to a clinic, but falls into a well and drowns or falls victims to murderous robbers along the way, X is not guilty of homicide. (Mentioned in Reid & Stratton) Where the intervening act is the act of a 3rd party, it must be free, deliberate, and informed. In particular, it must not be a reasonable act of self-defence (shooting back when being shot at) or an act done in the performance of a legal duty (under certain circumstances, a peace officer shooting at a criminal). (Pagett v The Queen) Acts by a 3rd party who is participating in a joint activity with the accused are not intervening acts – gun battle (R v SRJ); Street racing.

Pagett v The Queen (UKCA, 1983) (349) S v SRJ, ONCA, 2008 (351) FACTS: The accused shot at police officers while using FACTS: The accused and another engaged in a gunfight a 16-year-old pregnant girlfriend as a human shield. The in a crowded place. The other participant shot and killed police returned fire and killed the girl. an innocent bystander. ISSUE: Is the accused guilty of manslaughter? (CC 234, ISSUE: Is the accused guilty of manslaughter (CC 234, 222) (Yes) 222) even though his opponent that shot the fatal bullet? The police officer’s act was not an intervening cause (yes!) because it was a reasonable act of self defence and one Each participant induced the other to engage in the done in the performance of a legal duty. gunfight, the conduct of each is therefore a contributing cause of the victim’s death, according to the CML test. R v Reid and Stratton, NSCA, 2003 (352) R. v. Maybin, SCC, 2012 FACTS: R&S got in a fight with the victim. One put the FACTS: In a bar, T and M Maybin repeatedly punched victim into a headlock (the other kicked him), causing the victim in the face and head. The victim went him to loose consciousness. Medical evidence suggested unconscious. A bar bouncer then struck the victim in the he would have regained consciousness after a couple of head. The medical evidence was inconclusive about minutes. However, friends performed CPR badly while which blows caused death. they took him to the hospital, causing him to choke on ISSUE: Were the accused’s actions a significant his own vomit and die. contributing cause of death such that they are guilty of

9 ISSUE: Was the CPR an intervening act that broke the manslaughter (CC 234, 222)? (Yes) chain of causation such that R&S are not guilty of Application of foreseeability: though the blow of the manslaughter (CC 234, 222)? (Possibly - New trial bouncer may not have been foreseeable, the intervention ordered) of bar staff generally, and the possibility that their intervention would harm the victim, was foreseeable Application of intervening act analysis: the bouncer’s blow was connected to the accused’s. It was not a coincidence

Mens Rea

Objective considerations as evidence for subjective state of mind Though mans rea concerns subjective state of mind people generally know and intend the objectively natural consequences of their actions. Thus, where X is an objectively natural consequence of Y, and where the accused did Y, the finder of fact may draw a “common sense inference” that the accused intended X (Buzzanga; Tennant)

Relationship between desire and intent The fact that a person who commits a criminal act does so as a result of threats may, for certain offences, negate mans rea required for the offence (R v Steane). More often, however, it will not (R v Hibbert). Rather, the court will examine duress as defense subsequent to establishing mens rea. Determining which is the case involves interpreting the relevant provision – deciding whether, read in its entire context, the provision is intended to allow duress to negate the mans rea (Hibbert)

R v Steane, UKKB, 1947 (429) R v Hibbert, SCC, 1995 (432) FACTS: Steane was in Germany during the war and FACTS: The accused, under threat, lured a victim out of forced to do news broadcasts for the Nazis, on threat of his/her apartment, and the accused’s companion shot the his family being sent to a concentration camp. He was victim in the lobby. accused under a wartime regulation which provided, “If ISSUE: Did the accused have the mans rea for aiding with intent to assist the enemy, any person does any act under 21(1)(b) such that he is guilty of attempted murder which is likely to assist the enemy…then…he shall be (citation)? (no) guilty of an offence…” The defense of duress does not negate the mans rea for ISSUE: Did Steane have the intention to assist the aiding under 21(1)(b)? enemy? (No.) Why? The CC aiding provision cannot have been Steane’s action was not intentional because he was intended to only include persons who wished to aid. motivated by the desire to protect his family. Why? This crime cannot have been intended to capture persons such as Steane.

Distinguishing intention from motive (R v Lewis ) Intent: the exercise of a free will to use particular means to produce a particular result Motive: ulterior intention -- that which precedes and induces the exercise of the will Motive is legally irrelevant to criminal responsibility. As evidence, presence of motive is relevant in proving identity or intent “he had reason to do it, therefore he must have did it and meant to do it”. Conversely, absence of motive helps raise a reasonable doubt as to identity or intent “he had no reason to do it, therefore, he may well not have done it or not meant to do it”

Subjective states of mind Intent (“willfully”)

10 David Sum’s Crim Law Summary, Professor Klein, Summer 2015 Drop me a line if this has been helpful!

Where the mens rea for an act or consequence requires intent, generally, a person intends a consequence either if: a) she is resolved to bring about that consequence or b) she is certain or substantially certain that the consequence will follow from her act, even if which she performs her act to achieve some other purpose, rather than the consequence (Buzzanga) Recklessness: For certain offences, a mens rea intent requirement may extend to recklessness. Recklessness involves engaging in conduct even while knowing that this conduct creates a risk that the prohibited result will occur. (Sansregret) Actual knowledge / “knowlingly” Where the mens rea requires that the accused committed an act “knowingly” in respect of some fact or circumstance, generally, this implies either having no doubt concerning a fact, or suspecting that a fact is probably true (Theroux). Willful blindness: for certain offences, a mens rea actual knowledge requirement may extend to willful blindness. Willful blindness arises where a person has become aware of the need for some inquiry but declines to make the inquiry because he does not wish to know the truth (Sansregret; Briscoe)

R v Buzzanga, ONCA, 1979 R v Theroux, SCC, 1993 (442) R v Sansregret, SCC, 1985 (447) FACTS: B and D published FACTS: The accused accepted FACTS: S’s girlfriend consented to inflammatory pamphlets about the deposits having told investors that he sex in order to stop S from beating Francophone population in their ON had purchased deposit insurance her. community. They testified the when in fact he had not. ISSUE: Was S willfully blind to the pamphlets were satirical, intended to ISSUE: Is the accused guilty of fact that his girlfriend’s consent was show the absurdity of the arguments fraud (CC 380(1))? (unclear). vitiated by fear (CC 265(3)(b) such against a French high school, and Elements of Fraud that the “accused’s belief as to therefore lead to its being built. Actus reus: consent” defense (CC 265(4) fails 281.2(2) [hate speech – now 319] Prohibited act: deceit, and he is guilty of sexual (CC 271) was worded, at the time, as falsehood, other dishonest act assault (CC 265(1))? (Yes) “willfully promotes hatred.” Prohibited consequence: ISSUE: Did the accused “willfully Depriving another of what is or promote hatred” such that they are should be his guilty of hate speech (now CC 319)? Mans rea: (maybe – new trial) Subjective knowledge of the They willfully promoted hatred if prohibited act -- knowing the they were resolved to bring about act constituted deceit, falsehood, hatred or if they forsaw hatred was or some other dishonest act. certain or substantially certain. Subjective knowledge of the prohibited consequence – knowing that the act might deprive another of what is or should be his.

What about ADH?

Objective States of Mind

History The SCC only recognized the possibility of a criminal offense based on an objective fault requirement in the 1993 case, Hundal. Before Hundal, to the frustration of lower courts (Gingrich and McLean) the SCC repeatedly split (Tutton & Tutton, R v Waite): certain judges were prepared to recognize an objective fault requirement, others were not. Rationale?

True crimes are presumed to require a subjective fault element. This presumption reflects the principle that the morally innocent should not be punished (ADH)

11 To determine whether this presumption is rebutted, engage in legislative interpretation (ADH)

The CC contains 5 categories of objective fault offences: ( ADH ) (1) Dangerous conduct offences. E.g.. dangerous driving causing death (CC 249(4); Hundal; R v Beatty; R v Roy) Actus reus: driving in a manner dangerous to the public, having regard to all of the circumstances (road conditions, place, traffic, etc.) (Beatty, Roy) Requires a meaningful inquiry into the manner of driving. Insufficient that driving caused damage. Driving is risky. The occurrence of damage does not indicate that the manner of driving was necessarily dangerous. Mens rea: a marked departure from the standard of care that a reasonable driver would have observed. (Beatty, Roy) Personal characteristics and state of mind are irrelevant, unless they show that a reasonable person in the same circumstances would not or could not have behaved differently. Thus, incapacity and mistake of fact defenses may succeed. Why? A marked departure is required because simple carelessness is not morally blameworthy. This is a “modified objective test” it differs from the objective test for civil liability. Civil liability is concerned with the apportionment of loss. Criminal liability is concerned with the punishment of blameworthy conduct. (Beatty, Roy) The modified objective test requires a marked departure from the reasonable person standard because anything less – e.g. simple carelessness – is not morally blameworthy, and it is a principle of fundamental justice that the morally blameworthy not be punished (s7)

R v Beatty, SCC, 2008 R v Roy, SCC, 2012 FACTS: B suffered a momentary lapse in consciousness FACTS: The accused pulled into the incorrect lane of a (fell asleep) while driving, swerved into oncoming difficult snow-covered intersection on a foggy day. A traffic, and collided with another vehicle, killing its 3 truck collided with the accused’s vehicle and killed his occupants. passenger. ISSUE: Was the accused’s conduct a marked departure ISSUE: Was the accused’s conduct a marked departure from what that of a reasonable driver such that he is from what that of a reasonable driver such that he is guilty of dangerous driving causing death (CC 249(4))? guilty of dangerous driving causing death (CC 249(4))? (no) (no) The accused, an otherwise safe driver faced difficult road conditions, pulled into a poorly designed intersection when he should not have. This was objectively dangerous (actus reus established). It constituted, however, a momentary lapse in judgment rather a marked departure from the conduct of a reasonable driver.

(2) Careless conduct offences (Finlay), e.g. CC 86 [careless storage of firearms]. ( ADH ) Key term: “in a careless manner”, “reasonable precautions”

(3) Offences requiring the commission of an underlying unlawful act (e.g. unlawful act manslaughter, unlawfully causing bodily harm), along with the mental requirement for the underlying unlawful act, plus objective foreseeability of harm flowing from the unlawful act e.g. unlawful act manslaughter (CC 222(5)(a) with CC 236, CC 234; DeSousa, Creighton) The mens rea for manslaughter is objective foreseeability of bodily harm that is neither trivial nor transitory (Creighton) “the implicit rationale of the law in this area is that it is acceptable to distinguish b/t criminal responsibility for equally reprehensible acts on the basis of the harm that is actually caused” (Creighton) Come back to this.

(4) Criminal negligence offences (CC 219, 220) ( ADH )

12 David Sum’s Crim Law Summary, Professor Klein, Summer 2015 Drop me a line if this has been helpful!

Key term: “negligence” criminal negligence requires a marked and substantial departure from the conduct of a reasonably prudent person in circumstances in which the accused either recognized and ran an obvious and serious risk or, alternatively, gave no thought to that risk (R v JF) Tutton v Tutton was criminal negligence, so was R v Brown. I don’t think this is going to come up though!

(5) Duty based offences based around CC 215 ( ADH ).

Absolute and Strict Liability

Definitions True crimes are acts so morally abhorrent that they ought to be prohibited completely, and that they must be condemned and punished where they are committed (Wholesale Travel). Mans rea is required for such crimes due to the fault and moral culpability they imply. True crimes are punished because they are morally abhorrent, but no conduct is morally abhorrent if it is innocent, thus innocent conduct cannot constitute a true crime. Concerned with values rather than results. Carry a stigma of moral blameworthiness. Regulatory offences (aka public welfare offences) involve conduct that is not inherently wrongful, but that must be regulated to avoid dangerous conditions being imposed on members of society, especially vulnerable ones (Wholesale Travel). Purpose: to prevent future harm through enforcement of minimum standards. Concerned with results rather than values. Tend not to carry a stigma of moral blameworthiness. Mans rea liability requires both actus reus and mans rea. The accused is only liable if performed the prohibited act while holding the required state of mind. Absolute liability requires actus reus, but no mans rea. The accused is liable if he performed the prohibited act, irrespective of his intentions. Strict liability is a middle ground between mans rea liability and absolute liability. The crown only bears the burden of proving the actus reus. The defendant may escape liability by proving on the balance of probabilities that all due care was taken (defense of due diligence). (Sault ste Marie)

Interpretation: What type of mans rea does this offence require? True crimes are presumed to include a mans rea requirement (Beaver) Absent the Charter, with clear language, Parliament may (thanks to Parliamentary sovereignty) impose strict or absolute liability for true crimes (Beaver). The Charter restricts this ability (). Regulatory offences are interpreted free of any presumption that mans rea is required (Pierce Fisheries). By default, liability for regulatory offences is strict (Sault Ste. Marie). Parliament may impose a mans rea requirement for regulatory offences. If a provincial legislature government attempts to do so however, it may be encroaching on the Federal Government’s criminal law power (Salut Ste Marie).

Beaver v The Queen, SCC, 1957 R v Pierce Fisheries, SCC, 1971 R v Sault Ste Marie, SCC, 1978 (378) (384) (388) FACTS: B sold heroin, saying it was FACTS: PF was caught with 26 FACTS: City charged with a heroin, but believing it was fake. undersized lopsters in his traps, out provincial offence of polluting a ISSUE: Is B guilty of possession or of 60 k lbs. of lobster. river. trafficking under the Opium and ISSUE: Is PF guilty of an offence Comes up with a middle ground – Narcotic Drug Act even though he which prohibited fishing undersized strict liability. thought the heroin was fake? lobster? (yes) Court here is recognizing the (possession – no; trafficking – yes) This is a regulatory offence, for harshness of absolute liability, and Innocent of possession because this which there is no presumption a developing a mechanism to deal

13 is a true criminal offence, true mens rea is required. The statute with it, even in absence of Charter. criminal offences are presumed to does not appear to require one, so it require a subjective mens rea, and should not be read in. the presumption is not rebutted here. Guilty of trafficking because act did not require belief it was actually a drug: “represented or held out to be a drug”.

Constitutionality: Is the reduced mans rea requirement imposed constitutional? Is liability absolute, or is less than the due diligence defense available? Absolute liability offends the principle of fundamental justice that the innocent not be punished (BC Motor Vehicle). Thus, an absolute liability offence infringes s7 where its penalty implicates a life, liberty, or security of the person interest (BC Motor Vehicle). In order to comply with the principles of fundamental justice, at least a full due diligence offence must be available. Thus, an offence for which the due diligence is unavailable infringes s7 where its penalty implicates a life, liberty, or security of the person interest (BC Motor Vehicle as interpreted by Wholesale Travel). Conversely: an offense with the mental element of negligence does not generally infringe s7, if the full defense of due diligence is available. (Wholesale Travel) Exception: For certain offenses, the degree of stigma attaching to a conviction and/or the severity of the available punishment is such that subjective mans rea is constitutionally required by s7 (Vallancourt, cited in Wholesle Travel) – this is an intricacy that is escaping me to a degree. Is a s7 interest implicated? Imprisonment implicates a liberty interest under s7 (BC Motor Vehicle) Serious state-imposed psychological stress, for example via the stigma associated with a criminal conviction, may implicate a security of the person interest under s7. However, courts have been reluctant to recognize this under particular circumstances (Transport Robert) Section 11(d) If an accused bears the burden of disproving on the balance of probabilities, any essential element of an offence, a conviction may occur in spite of a reasonable doubt. This infringes s 11(d), which requires that the accused is presumed innocent until the crown proves the accused’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt (Oakes) Thus, strict liability offences infringe 11(d) (Wholesale Travel, except Cory+1, who said no infringement). Strict liability offences may, however, be justifiable under s 1 (Wholesale Travel, per Iacobucci +2) 11(d) does not prevent Parliament from defining an offence so as to eliminate an element or common law defense. Thus, absolute liability offences do not infringe 11(d) (Transport Robert). ??? Rules of Thumb Liability is absolute Does not infringe 11(d) (Transport Robert) Infringes s7 if life, liberty, security if the person interest is implicated (BC Motor Vehicle) Does not infringe s7 if no such interest is implicated (Transport Robert) Liability is more than strict (full due diligence defense not available) 11(d) – unclear Infringes s7 if life, liberty, security if the person interest is implicated (BC Motor Vehicle, as interpreted by Wholesale Travel) Does not infringe s7 if no such interest is implicated Liability is strict (full due diligence defense available) Infringes 11(d) (Wholesale Travel, except Cory+1, who said no infringement), but this may be justifiable under s 1 (Wholesale Travel, per Iacobucci +2) Does not infringe s7, even if life, liberty, security if the person interest is implicated (), unless the degree of stigma attaching to a conviction and/or the severity of the available punishment is such that subjective mans rea is constitutionally required by s7 (Vallancourt, cited in Wholesale Travel) – this is an intricacy that is escaping me to a degree. Mans Rea liability

14 David Sum’s Crim Law Summary, Professor Klein, Summer 2015 Drop me a line if this has been helpful!

Re BC Motor Vehicle Act, SCC, 1985 (395) R v Transport Robert, ONCA, 2004 (401) FACTS: The Act imposes a mandatory prison sentence FACTS: Wheels flew off some trucks. ON’s Highway for driving on a suspended license, and explicitly Traffic Act renders the owner of a truck that has its classifies this as an absolute liability offense. wheels fly off guilty of an absolute liability offence. No ISSUE: Is the Act constitutional under s7? (no). imprisonment. It infringes s7 to combine absolute liability with ISSUE: Does this offence violate s7 or s11(d) (no) imprisonment. 11(d) prohibits the reversal of the burden of proof, but does not prevent eliminating an element of an offence. 7: no liberty or security of the person interest (nice try) implicated R v Wholesale Travel Group, SCC, 1991 (406) FACTS: WTG charged with “false or misleading advertising”, contrary to s36(1)(a) of the Competition Act on the basis that it wrongly advertised that its travel packages as “wholesale”. A full due diligence defense unavailable (see pg. 406 for provision). Prison sentence possible. ISSUE #2 (pg. 409-411): Would the offence infringe s7 were a full due diligence offence available? (no) An offense with the mental element of negligence does not generally infringe s7, if the full defense of due diligence is available. ISSUE: #3 (407-409) Does the provision violate S7 because it may impose prison time and does not permit a full due diligence defense? (Yes!) An offence carrying the threat of imprisonment infringes s7 unless at least the defense of due diligence is available. ISSUE: #4 (411-415) Does the reverse onus violate 11d (right to be presumed innocent)? (No) Iacobucci+2 (majority): Infringes 11(d) but justified under s1. The Law Reform Commission approach would not accomplish the objective of difficulty of proving negligence at the criminal threshold, reducing the effectiveness of the provisions Cory+1: (majority) Does not infringe s11(d). Lamer C.J. (+3, dissent): Infringes 11(d), unjustifiable under s1. Fails s1 at minimal infringement. Alternative possibility would be to adopt the Law Reform Commission approach: Once the potential defense of due diligence is raised (evidentiary burden on accused), Crown would have to prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that it did not apply (persuasive burden on the crown).

Homicide

Actus Reus – Homicide (CC 222) For all forms of culpable homicide, the actus reus is to cause the death of a human being (CC 222(1) by one of the means enumerated in CC 222(5). “ causes the death of…” (CC 222(1)) -- Causation in criminal law consists of factual and legal causation (Maybin). FACTUAL: The crown establishes factual causation where it proves, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the victim would not have died but for the accused’s act (Maybin). LEGAL: The crown establishes legal causation where it proves, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the accused’s conduct was a “significant contributing cause” of the accused’s death (Smithers, as reformulated in Nette). This standard of causation applies to all homicide offences – manslaughter, 2nd degree murder, and 1st degree murder. (Nette) THIN SKULL: The criminal must take his victim as he finds him. Thus, if the accused’s act was a “significant contributing cause” of the accused’s death (Smithers, Nette), causation is established, even if the accused’s act would not normally cause death, but only caused death due to some weakness of the victim (Smithers; Blaue) SEE ALSO, LEGAL CAUSATION SECTION INTERVENING CAUSE: The accused is not guilty where an intervening cause breaks the chain of causation between the act of the accused and the consequence element of the offence such that the accused’s act is not a significant contributing cause of the prohibited consequence (Maybin, Reid & Stratton).

15 Foreseeability and intervening act approaches are merely helpful interpretive aids (Maybin) Acts by a 3rd party who is participating in a joint activity with the accused are not intervening acts – gun battle (R v SRJ); Street racing. SEE ALSO INTERVENING CAUSES SECTION Enumerated means (CC 222(5)(a)-(d)) “by means of an unlawful act” (CC 222(5)(a)) Unlawful act here generally means “criminal” (Klein, class). “by criminal negligence” (CC 222(5)(b)) SEE CC 219(1) “ a human being” (CC 222(1)) “Human being” in 229(b) means “another human being” (Fountaine, MBCA) – this is unlikely to be important here, given that there isn’t (and couldn’t be) an offence in the CC for “attempted manslaughter”.

Manslaughter The mens rea for unlawful act manslaughter (CC 222(5)(a), 234) is the mens rea of the underlying offence, plus objective foreseeability of bodily harm that is neither trivial nor transitory (Creighton). The underlying offence cannot be an absolute liability offence (Creighton) Personal characteristics are irrelevant where for objective fault offences, except if they establish the accused’s incapacity to appreciate the nature and risks of her conduct. (Creighton)

Murder (CC 229) CC 229-230 set out several mens rea requirements that are sufficient for murder. A murder conviction invariably requires subjective foresight of death (obiter in Vaillancourt, affirmed as ratio in Martineau). CC 229(a)-(c) specify three circumstances under which there is subjective foresight of death such that culpable homicide under CC 222(5) constitutes murder. INTENT: Culpable homicide is murder where the accused “means” to cause the victim’s death (CC 229(a)(i)) Murder under CC 229(a) requires subjective foresight of death (Simpson) Where the mens rea for an act or consequence requires intent, generally, a person intends a consequence either if: a) she is resolved to bring about that consequence or b) she is certain or substantially certain that the consequence will follow from her act, even if which she performs her act to achieve some other purpose, rather than the consequence (Buzzanga) RECKLESSNESS: Culpable homicide is murder where the accused means to cause the victim bodily harm that he knows is likely to cause his death (CC 229(a)(ii)) Murder under CC 229(a) requires subjective foresight of death (Simpson) This branch of murder requires a) subjective intent to cause bodily harm and b) subjective knowledge that the bodily harm will likely result in death (Cooper). TRANSFERRED INTENT: Under CC 229(b), culpable homicide is murder where the accused intends (pursuant to CC 229(a)) the death of one person but causes the death of another. Under these circumstances, the intent associated with one person’s death transfers to that of another (Fontaine). CC 229(b) does not, however, render suicide murder, or attempted suicide attempted murder (Fontaine). UNLAWFUL OBJECT: Culpable homicide is murder “where a person, [a] for an unlawful object, [b] does anything that [c] he knows or ought to know is likely to cause death, and thereby [d] causes death to a human being, notwithstanding that he desires to effect his object without causing death or bodily harm to any human being” (CC 229(c); JSR). The words, “or ought to know” in CC 229(c) are unconstitutional, as they would result in a murder offence requiring only objective, rather than subjective, foresight of death (Martineau). Nordheimer J of the ONCA upheld the constitutionality of CC 229(c) (JSR #2). FELONY MURDER (unconstitutional and repealed): Under the CC 230, homicide is murder where an accused caused a victim’s death while committing or attempting to commit one of certain enumerated offences, and

16 David Sum’s Crim Law Summary, Professor Klein, Summer 2015 Drop me a line if this has been helpful!

where, for example, the accused meant to cause bodily harm to facilitate the commission of the offence (see text pg. 702 for provision). Vaillancourt invalidated what was then CC 219(d) on the basis that it did not require even objective foreseeability of death. Martineau invalidated CC 231(a) on the basis that it did not require subjective foresight of death.

1 st degree or 2 nd degree murder CC 231 classifies murder for the purposes of sentencing after a person has been convicted of murder. The provision reflect Parliament’s view that the increased blameworthiness associated with certain aggravating factors warrants a particularly harsh sentence (Luxton, Harbottle) PLANNED: Murder is in first degree when it is planned and deliberate (CC 231(2)) Planned: a calculated scheme or design which has been carefully thought out and the nature and consequences have been considered and weighted. Time must have been taken to plan (not the time between the plan and the action). (Widdifield, ONSC) Deliberate: “considered, not impulsive”, (More) “slow in deciding”, “cautious”. A must take time to weigh the advantages and disadvantages of his intended action (Widdifield, ONSC) CC 229(a)(ii) and 231(2) may be combined. That is, where an accused hatches and deliberately carries out a plan to cause bodily harm that he subjectively knows will likely cause death, she is guilty of first degree murder (Nygaard) POLICE OFFICER: Murder is in the first degree when the victim is a police officer, or similar (CC 231(4)) To have a murder classified as 1st degree under CC 231(4)(a), the crown must prove that the accused knew the victim was a police officer etc. UNDERLYING DOMINION OFFENCE: Murder is in the first degree when “the death is caused by [the accused] while committing or attempting to commit an offence under one of the following sections: (a) section 76 (hijacking an aircraft); (b) section 271 (sexual assault); (c) section 272 (sexual assault with a weapon, threats to a third party or causing bodily harm); (d) section 273 (aggravated sexual assault); (e) section 279 (kidnapping and forcible confinement); or (f) section 279.1 (hostage taking) “is caused by”: for a murder to be classified as 1st degree, the accused’s act must have been a substantial and integral cause of the victim’s death (Harbottle). “While committing or attempting to commit” requires the killing to be closely connected, temporally and casually, with an enumerated offence. As long as that connection exists, it is immaterial that the victim of the killing and the victim of the enumerated offence are the same (Russell) “while” -- Where the act causing death and the acts constitution the rape, attempted rape, indecent assault or an attempt to commit indecent assault, all form part of one continuous sequence of events forming a single transaction – such that the murderer continues, at the time of murder to illegally dominate the victim – the death was caused “while committing” an offence for the purposes of s.231(5) (Paré) CC 231(5) is not unconstitutional: s7: CC 231(5) reflects a reasoned decision on the part of Parliament to treat murders committed in the context of illegal domination as more serious than others. This distinction is neither arbitrary nor irrational, and thus does not offend the principles of fundamental justice (Arkell) s9 – right not to be arbitrarily detained or imprisoned (Luxton) s12 – cruel and unusual punishment (Luxton)

Sentences for murder The mandatory minimum sentence for first degree murder is life imprisonment (CC 235(1)), with eligibility for parole only after 25 years (CC 745(a)). The mandatory minimum sentence for 2nd degree murder is life imprisonment (CC 235(1)), with eligibility for parole only after 10 years, (CC 745(c)), or, at the discretion of the judge, after 10-25 years (CC 745(c)). For a 2nd 2nd degree murder conviction, eligibility for parole only begins after 25 years. (CC 745(b))

17 The maximum sentence for manslaughter is life imprisonment. (CC 236). There is no mandatory minimum sentence, unless a firearm is used in the commission of the offence, in which case a 4 year minimum applies (CC 236(b)).

Attempt to commit murder – CC 239

Provocation The defense of Provocation (CC 232(1)) provides a partial defense to murder. Where it is successful, it reduces murder to manslaughter. This is important because [SENTANCING INFO]. BURDEN: The evidentiary burden for the defence of provocation (like all defences) lies with the accused, but the persuasive burden lies with the crown. That is, where the accused raises some evidence to suggest provocation, the crown must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that there was no provocation (Thibert) AIR OF REALITY: A judge should leave the provocation defence with a jury only if it bears an air of reality; only if there is (a) some evidence to suggest the victim’s wrongful act would cause the ordinary person to be deprived of self control, and (b) some evidence showing the accused was actually deprived of his self control (Thibert). The provocation defense consists of an objective and a subjective element. The objective element requires (i) a wrongful act or insult (ii) of such a nature that it is sufficient to deprive an ordinary person of the power of self-control. (CC 232(2); Thibert; Tran; Mayuran). (i) wrongful act or insult insult: “[a]n act or the action of attacking; (an) attack, (an) assault.” Likewise, the action of insulting means to “[s]how arrogance or scorn; boast, exult, esp. insolently or contemptuously. . . . Treat with scornful abuse; subject to indignity; . . . offend the modesty or self-respect of.” (Tran) In Tran, the victim and her lover’s sexual relations did not constitute an insult because they occurred in private and were passive with respect to the accused (the victim’s ex-husband). CC 232(3) narrows the defense of provocation, precluding its use where the victim’s conduct was pursuant to a “legal right”. The meaning of “legal right”, however, only including only conduct sanctioned by law, rather than conduct that is not illegal (Thibert). That is, 232(3) only precludes the defense of provocation where the law specifically empowered the victim to do whatever was apparently provocative (Thibert) For example, the defense is not available where the apparently provocative conduct was in self defense, or was the conduct of a sheriff executing a legal warrant. (Thibert) (ii) “Nature that is sufficient to deprive an ordinary person of the power of self-control” The “ordinary person” of CC 232(2) connotes a “contextualized” objective standard that takes into account the non-idiosyncratic characteristics and circumstances of the accused, insofar as this does not “subvert the logic of the objective test for provocation” (Hill; Tran). The “ordinary person” has a normal temperament and level of self-control (Hill). He is not “exceptionally excitable” or drunk (Hill). He is the same age and gender as the accused (Thibert). He shares with the accused non-idiosyncratic characteristics that would give the act or insult at issue special significance (Hill). The characteristics of the “ordinary person” are informed by contemporary norms of behaviour, including the Charter (Tran) Beliefs contrary to Canadian values ought not to be imported into the ordinary person test for the provocation defence (Humaid) The subjective element requires that (i) the accused acted upon that insult (ii) abruptly (“on the sudden”) before there was time for her passion to cool (CC 232(2); Thibert; Tran; Mayuran). (i) the accused acted upon that insult The defence fails if the accused was not provoked; was not influenced be the insult – even if the “ordinary person” would have been (Hill)

18 David Sum’s Crim Law Summary, Professor Klein, Summer 2015 Drop me a line if this has been helpful!

Can take account of mental state of accused at the time of the insult or act (Hill). Again, background and history of relationship between accused and victim must be considered (Thibert). (ii) before there was time for her passion to cool This requirement distinguishes conduct taken in response to provocation from conduct taken in revenge (Tran) However, provocation that induces a desire for revenge may qualify (Thibert) For example, in Tran, the fact that the accused’s ex-wife had sexual relations with another did not constitute provocation because the accused was already aware of these relations.

MISSING IN THIS SECTION Relationship between the mens rea for murder and provocation. Cultural issues -- Klein wants to underline that it is impossible to have a defence of provocation that is not intimately tied to a particular culture. The defence of provocation conveys something about the culture of the criminal law or the dominant culture that is reflected by the criminal law, which is informed by sexism and heternormativity.

DEFENSES GENERALLY

Air of Reality A judge must only put a defence to the jury (or where there is no jury, to himself) if it bears an “air of reality”; if there is evidence upon which a reasonable jury could find that the defence succeeds (Tran). Evidentiary Burden The evidentiary burden of proof for a defence lies with the accused. It is up to the accused, that is, to raise some evidence in support of a defence. The persuasive burden of proof, however, rests on the crown. To secure a conviction, that is, the crown must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that at least one of the elements of the defence is absent (Tran).

The content of the ‘air of reality’ threshold test comes from the 2002 R v Cinous, which we are not reading. Any defence must possess an ‘air of reality’ before being put to the jury, that is, "if a properly instructed jury acting reasonably could acquit the accused on the basis of the defence."

Sexual Assault

Actus Reus The actus reus for sexual assault is (3) unwanted (2) sexual (1) touching (Ewanchuk). (1) TOUCHING – First, regarding “touching”, sexual assault (CC 271) is a form of assault (CC 265), and mere touching constitutes an “application of force” for the purposes of assault (R v Burden in annotated code). Whether there was touching is determined objectively (Ewanchuk). (2) SEXUAL NATURE – Second, the “sexual” requirement is objective. An assault is sexual in nature, that is, where a reasonable observer would, in light of the circumstances, view it as such (Chase). It is irrelevant whether the accused considered the touching to be sexual in nature. Relevant considerations include the part of the body touched, the nature of the contact, the situation, words and gestures, threats with or without force, and motive of the accused (e.g. sexual gratification). Motive is not determinative (Chase) The “sexual nature” requirement is generally easy to meet (R v V – dad grabs kid’s genitals to teach him not to grab other’s genitals). (3) UNWANTED

19 Third, “unwanted” means that the complainant did not consent – voluntarily agree – to the sexual activity in question (CC 273.1(1)). It concerns, that is, the subjective state of mind of the complainant (not the accused) (Ewanchuk). The representations of a 3rd party do not constitute the complainant’s consent (CC 273.1(2)(a), CASE) The following all vitiate consent: The application of force (CC 265(3)(a)) Threats or fear (CC 265(3)(b)) Fear (CC 265(3)(b)) need not be reasonable (subjective fear), need not be communicated – established where the complainant believes herself to have only 2 choices: comply or be harmed (Ewanchuk) Fraud (CC 265(3)(c)) Failure to disclose HIV+ status before having sex vitiates consent by fraud where there is: (Currier) (1) a dishonest act – falsehoods or a failure to disclose (2) deprivation – denying the complainant knowledge which would have caused her to refuse sexual relations that exposed her to a significant risk of serious bodily harm. A “significant risk of serious bodily harm” means a “significant risk of transmission”. It is absent where the accused’s viral load is low and a condom is used. It is present where a condom is not used while the viral load is low or where a condom is used but the viral load is high (Mabior). The exercise of authority (CC 265(3)(d)). Inducement by abusing a position of trust, power or authority (CC 273.1(2)(c)) Incapacity (CC 273.1(2)(b)) Saying “no” or otherwise expressing, by words or conduct, a lack of agreement (CC 273.1(2)(d); Ewanchuk) Retraction of consent (CC 273.1(2)(e)) Because consent may be retracted, and it is impossible to retract consent while unconscious, consent cannot be given while unconscious (R v JA; see also incapacity – CC 273.1(2)(b))

Mens Rea The mens rea for sexual assault includes (1) an intention to touch and (2) knowledge of or willful blindness to the complainant’s lack of consent (Ewanchuk). With respect to the second requirement, honest but mistaken belief in consent (CC 265(4)) is a defense which negates the mens rea for sexual assault (Ewanchuk). ACTIVE -- Consent in the context of mens rea must be active. That is, sexual touching does not constitute sexual assault where the accused honestly believed that (or where there is a reasonable doubt that) the victim affirmatively communicated her agreement to the touching. Belief that silence, passivity or ambiguous conduct constituted consent is no defense (Ewanchuk). ONGOING -- Consent must also be ongoing. If there was a ‘no’, consent must be re-established (Ewanchuck; CC 273.1(2)(e)) AWARENESS OF VITIATION See also the other provisions above, regarding factors which vitiate consent. If the accused is aware of any of these factors, the defense fails. For example, if the accused is aware that the complainant’s consent is induced by abusing a position of trust, power or authority (CC 273.1(2)(c)), the defense fails. WILFUL BLINDNESS -- The honest but mistaken belief in consent defense fails where the accused was wilfully blind to the complainant’s lack of consent. Wilful blindness arises where a person has become aware of the need for some inquiry but declines to make the inquiry because he does not wish to know the truth (Sansregret; CC 273.2(a)(ii)). REASONABLE STEPS -- The accused must take some reasonable steps, “in the circumstances known to the accused at the time”, to ascertain the complainant’s consent, before engaging in sexual activity (CC 273.2(b)). This does not imply, however, that the accused’s honest but mistaken belief in consent be reasonable. Where the accused takes some reasonable steps to ascertain consent, but nevertheless comes to an unreasonable yet honest mistaken belief that the complainant has consented, the defense may succeed (Darrach; Cornejo)

20 David Sum’s Crim Law Summary, Professor Klein, Summer 2015 Drop me a line if this has been helpful!

Criticism: One would have thought that a requirement to take “reasonable steps” would imply a requirement not to make an unreasonable mistake, but the ONCA found otherwise. A person can take some reasonable steps, still be left with an unreasonable belief that the complainant consented, and be acquitted on this basis. (Boyle and MacCrimmon) AIR OF REALITY -- As is the case with all defences, a judge must only put the defence of honest but mistaken belief in consent to the jury (or where there is no jury, to himself) if it bears an “air of reality”; if there is some evidence in support of the accused’s belief such that a trier of fact, acting reasonably could entertain a reasonable doubt (Pappajohn, Ewanchuk, Cinous). BURDEN -- As is the case with all defences, the tactical burden of proof for the defence of honest but mistaken belief in consent lies with the accused. It is up to the accused, that is, to raise some evidence in support of the defence. The persuasive burden of proof, however, rests on the crown. To secure a conviction, that is, the crown must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that one of the elements of the defence is absent – that in fact there was knowledge or wilful blindness with respect to the complainant’s lack of consent (Osolin, also drawing from Tran re: the defence of provocation).

Charter Concerns CC 273.2(b) does not violate the Charter. See Darrach, plus Boyle and MacCrimmon’s criticism of the case. Regarding constitutionality of rape shield provisions, see Seaboyer, and also pg. 669 of annotated code.

Necessity

CC s 8(3) preserves the CML defense of necessity (Morgentaler). There are three elements to the defense: (1) imminent peril or danger, (2) the absence of a reasonable legal alternative and (3) proportionality between the harm done and the harm avoided. (Perka, Latimer) Judges enforce these requirements strictly, carefully limiting the scope of the necessity defense (Morgentaler, Perka) BURDEN/AIR OF REALITY -- As with all defenses, the tactical burden to raise some evidence in support of the each element of the defense lies on the accused, but the persuasive burden lies on the crown. That is, to secure a conviction, once the accused raises evidence sufficient to lend the defense an “air of reality”, the crown must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that one or more of the aforementioned elements of the defense is absent (Perka, Latimer, also Tran, Oslin, etc. re: other defenses). A defense has an “air of reality if there is some evidence for the defence such that a trier of fact acting reasonably could acquit were it to believe the evidence is true (Cinous) (1) imminent peril or danger, The first element, that of imminence, is assessed on a modified objective standard. The relevant question is whether the accused in fact believed and whether a similarly situated reasonable person would have believed, that immediate peril or danger was present. This standard ascribes the accused’s personal circumstances and characteristics to the reasonable person insofar as these are relevant to a person’s ability to evaluate the urgency of a situation (Latimer). The peril, disaster, or harm must be direct and immediate. It is insufficient that it is merely foreseeable or likely. Rather, it must be “on the verge of transpiring and virtually certain to occur” (Latimer, Perka). (2) the absence of a reasonable legal alternative and The second element, that of no reasonable legal alternative, is also assessed on a modified objective standard. The relevant question is whether the accused in fact believed and whether a similarly situated reasonable person would have believed, that there was no reasonable legal alternative. This standard ascribes the accused’s personal circumstances and characteristics to the reasonable person insofar as these are relevant to a person’s ability to evaluate the available alternatives (Latimer). (3) proportionality between the harm done and the harm avoided. The third element, that of proportionality between the harm done and the harm avoided, is assessed on a straight objective standard (Latimer). The relevant question is whether a reasonable person would conclude that the harm caused by (accused’s act) was less than the harm that would have been caused by (if the accused didn’t act).