Variable Capacitors in RF Circuits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RF & Microwave Components & Systems Catalog

There is a new leader and source for your RF & microwave systems and components … Spectrum Microwave. Combining the people, products and technologies from FSY Microwave, Salisbury Engineering, Q-Bit, Magnum Microwave, Radian Technologies and Amplifonix into a single organization poised to provide a wide range of microwave solutions. Spectrum Microwave offers a worldwide network of sales, distribution and manufacturing locations that gives us a responsive local presence in North America, Europe and Asia. We’ve assembled an experienced engineering team that will help you select the right standard product or design a custom solution for your specific application. Our expanded product line now ranges from sophisticated microwave systems and integrated assemblies to advanced control components to ceramic filters and antennas. This diverse array of products includes technologies to satisfy both low cost commercial and high performance military applications. 2 rf microwave& components and systems Index Page Introduction Product Selection Guide . .5-9 Design & Testing . .10-11 RF & Microwave Solutions Development . .12-13 • Lumped element and cavity filters Cascade . .14-15 Specwave.com . .16 • BTS filters and tower mounted amplifiers About Spectrum Control . .17 • Waveguide and tubular filters • Ceramic bandpass filters and duplexers Frequency Control Components • Patch antenna elements and assemblies Amplifiers . .19-20 Mixers . .21-22 Voltage Controlled Oscillators (VCOs) . .23 Dielectric Resonator Oscillators (DROs) . .24 Attenuators, Detectors & Switches . .25-26 Coaxial Ceramic Resonators . .27-28 Custom Microwave Filters Filter Topology Selection . .30-33 Filter Considerations . .34 Frequency Ranges . .35 Lumped Element Filters . .36-38 Cavity Filters . .39-41 Waveguide Filters . .42-43 Tubular Filters . .44-45 Suspended Substrate Filters . -

Filtering and Suppressing Transients

Another EMC resource from EMC Standards EMC techniques in electronic design Part 3 - Filtering and Suppressing Transients Helping you solve your EMC problems 9 Bracken View, Brocton, Stafford ST17 0TF T:+44 (0) 1785 660247 E:[email protected] Design Techniques for EMC Part 3 — Filtering and Suppressing Transients Originally published in the EMC Compliance Journal in 2006-9, and available from http://www.compliance-club.com/KeithArmstrong.aspx Eur Ing Keith Armstrong CEng MIEE MIEEE Partner, Cherry Clough Consultants, www.cherryclough.com, Member EMCIA Phone/Fax: +44 (0)1785 660247, Email: [email protected] This is the third in a series of six articles on basic good-practice electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) techniques in electronic design, to be published during 2006. It is intended for designers of electronic modules, products and equipment, but to avoid having to write modules/products/equipment throughout – everything that is sold as the result of a design process will be called a ‘product’ here. This series is an update of the series first published in the UK EMC Journal in 1999 [1], and includes basic good EMC practices relevant for electronic, printed-circuit-board (PCB) and mechanical designers in all applications areas (household, commercial, entertainment, industrial, medical and healthcare, automotive, railway, marine, aerospace, military, etc.). Safety risks caused by electromagnetic interference (EMI) are not covered here; see [2] for more on this issue. These articles deal with the practical issues of what EMC techniques should generally be used and how they should generally be applied. Why they are needed or why they work is not covered (or, at least, not covered in any theoretical depth) – but they are well understood academically and well proven over decades of practice. -

Chapter 19 - the Oscillator

Chapter 19 - The Oscillator The Electronics Curse “Your amplifiers will oscillate, your oscillators won't!” Question, What is an Oscillator? A Pendulum is an Oscillator... “Oscillators are circuits that are used to generate A.C. signals. Although mechanical methods, like alternators, can be used to generate low frequency A.C. signals, such as the 50 Hz mains, electronic circuits are the most practical way of generating signals at radio frequencies.” Comment: Hmm, wasn't always. In the time of Marconi, generators were used to generate a frequency to transmit. We are talking about kiloWatts of power! e.g. Grimeton L.F. Transmitter. Oscillators are widely used in both transmitters and receivers. In transmitters they are used to generate the radio frequency signal that will ultimately be applied to the antenna, causing it to transmit. In receivers, oscillators are widely used in conjunction with mixers (a circuit that will be covered in a later module) to change the frequency of the received radio signal. Principal of Operation The diagram below is a ‘block diagram’ showing a typical oscillator. Block diagrams differ from the circuit diagrams that we have used so far in that they do not show every component in the circuit individually. Instead they show complete functional blocks – for example, amplifiers and filters – as just one symbol in the diagram. They are useful because they allow us to get a high level overview of how a circuit or system functions without having to show every individual component. The Barkhausen Criterion [That's NOT ‘dog box’ in German!] Comment: In electronics, the Barkhausen stability criterion is a mathematical condition to determine when a linear electronic circuit will oscillate. -

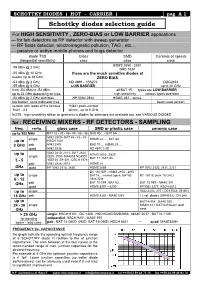

Schottky Diodes Selection Guide

SCHOTTKY DIODES ( HOT - CARRIER ) pag A 1 Schottky diodes selection guide For HIGH SENSITIVITY , ZERO-BIAS or LOW BARRIER applications --- for lab detectors as RF detector with sweep generator --- RF fields detector, electromagnetic pollution, TAG , etc… --- passive or active mobile phones and bugs detector diode TSS Glass SMD Ceramic or special (tangential sensitivity) case case case HSMS 2850 - 2851 -59 dBm @ 2 GHz SMS 7630 -55 dBm @ 10 GHz these are the much sensitive diodes at usable up to 18 GHz ZERO BIAS -53 dBm @ 2 GHz ND 4991 - 1SS276 DDC2353 -55 dBm @ 6 GHz LOW BARRIER up to 20 GHz from -54 dBm to -52 dBm all BAT 15… types are LOW BARRIER up to 24 GHz depending on type high sensitivity vatious types available -56 dBm @ 2 GHz with bias HP 5082-2824 HSMS.282…series low barrier, up to millimeter freq. beam lead version version with leads of the famous 1N821 point-contact 1N21 - 23 silicon , up to 5 GHz NOTE : high sensitivity silicon or germanium diodes for detectors are available too, see VARIOUS DIODES for : RECEIVING MIXERS - RF DETECTORS - SAMPLING freq. config. glass case SMD or plastic case ceramic case up to 500 MHz BAT 42 - 43 - 46 - 48 - 85 - 86 BAS 40-…- BAT 64-.... 5082.2800 - BAT 45 - 82 - 83 single HSMS 28.... , BAT 68 up to HSCH 1001 2 GHz pair 5082.2804 BAS 70... , HSMS 28... quad 5082.2836 ND 487C1-3R 5082.2810, 2811, 2817 2824, up to HSMS 2810 , 2820 single 2835, 2900, MA4853 ND4991 BAT 17 , BAT 68 3 - 5 1SS154 ,BA 481, QSCH 5374 pair 5082.2826, 2912 HSMS 28…. -

Special Diodes 2113

CHAPTER54 Learning Objectives ➣ Zener Diode SPECIAL ➣ Voltage Regulation ➣ Zener Diode as Peak Clipper DIODES ➣ Meter Protection ➣ Zener Diode as a Reference Element ➣ Tunneling Effect ➣ Tunnel Diode ➣ Tunnel Diode Oscillator ➣ Varactor Diode ➣ PIN Diode ➣ Schottky Diode ➣ Step Recovery Diode ➣ Gunn Diode ➣ IMPATT Diode Ç A major application for zener diodes is voltage regulation in dc power supplies. Zener diode maintains a nearly constant dc voltage under the proper operating conditions. 2112 Electrical Technology 54.1. Zener Diode It is a reverse-biased heavily-doped silicon (or germanium) P-N junction diode which is oper- ated in the breakdown region where current is limited by both external resistance and power dissipa- tion of the diode. Silicon is perferred to Ge because of its higher temperature and current capability. As seen from Art. 52.3, when a diode breaks down, both Zener and avalanche effects are present although usually one or the other predominates depending on the value of reverse voltage. At reverse voltages less than 6 V, Zener effect predominates whereas above 6 V, avalanche effect is predomi- nant. Strictly speaking, the first one should be called Zener diode and the second one as avalanche diode but the general practice is to call both types as Zener diodes. Zener breakdown occurs due to breaking of covalent bonds by the strong electric field set up in the depletion region by the reverse voltage. It produces an extremely large number of electrons and holes which constitute the reverse saturation current (now called Zener current, Iz) whose value is limited only by the external resistance in the circuit. -

RF Connector Overview Guide Linx Technologies Offers a Wide Variety of SMA, MCX, MMCX and MHF Radio Frequency Connector and Cable Assemblies

RF Connector Overview Guide Linx Technologies offers a wide variety of SMA, MCX, MMCX and MHF radio frequency connector and cable assemblies. RF connectors and cables consist of miniature precision-machined mechanical components and clever designs with complex assembly which are necessary to minimize losses and reflections. This requires tight tolerances, quality surface finishing and proper choice of metals and insulators. By combining domestic design and quality with offshore connector manufacturing, Linx offers low loss connectors at very competitive prices for OEM customers. – 1 – Revised 9/24/15 SMA Connectors Cable Termination SMA and RP-SMA Connecctors SMA (subminiature version A) connectors are high performance coaxial RF connectors with 50-ohm matching and Connector Body Orientation Mount Style Cable Types Polarity Part Numbers excellent electrical performance up to 18GHz with insertion loss as low as 0.17dB. They also have high mechanical Type Finish RG-174, RG-188A, Standard CONSMA007 strength through their thread coupling. This coupling minimizes reflections and attenuation by ensuring uniform SMA007 Straight Crimp End Plug Nickel RG-316 contact. SMA connectors are among the most popular connector type for OEMs as they offer high durability, low Reverse CONREVSMA007 RG-58/58A/58C, Standard CONSMA007-R58 VSWR and a variety of antenna mating choices. In order to comply with FCC Part 15 requirements for non-standard SMA007-R58 Straight Crimp End Plug Nickel RG-141A Reverse CONREVSMA007-R58 antenna connectors, SMA connectors are -

AM Transmitters

Chapter 4: AM Transmitters Chapter 4 Objectives At the conclusion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Draw a block diagram of a high or low-level AM transmitter, giving typical signals at each point in the circuit. • Discuss the relative advantages and disadvantages of high and low-level AM transmitters. • Identify an RF oscillator configuration, pointing out the components that control its frequency. • Describe the physical construction of a quartz crystal. • Calculate the series and parallel resonant frequencies of a quartz crystal, given manufacturer's data. • Identify the resonance modes of a quartz crystal in typical RF oscillator circuits. • Describe the operating characteristics of an RF amplifier circuit, given its schematic diagram. • Explain the operation of modulator circuits. • Identify the functional blocks (amplifiers, oscillators, etc) in a schematic diagram. • List measurement procedures used with AM transmitters. • Develop a plan for troubleshooting a transmitter. In Chapter 3 we studied the theory of amplitude modulation, but we never actually built an AM transmitter. To construct a working transmitter (or receiver), a knowledge of RF circuit principles is necessary. A complete transmitter consists of many different stages and hundreds of electronic components. When beginning technicians see the schematic diagram of a "real" electronic system for the first time, they're overwhelmed. A schematic contains much valuable information. But to the novice, it's a swirling mass of resistors, capacitors, coils, transistors, and IC chips, all connected in a massive web of wires! How can anyone understand this? All electronic systems, no matter how complex, are built from functional blocks or stages. -

RF/Microwave Connectors on Printed Circuit Boards

High Frequency Design CONNECTORS ON PCBs RF/Microwave Connectors on Printed Circuit Boards By Gary Breed Editorial Director hen mounting This month’s tutorial takes a an RF/micro- look at the practical matter Wwave or high of characterizing, then speed digital connector to installing, an RF connector a printed circuit board, on a printed circuit board the transition from the connector body and inner conductor pin to the printed traces is often the source of excessive mismatch. The discontinu- ity in size, shape and surrounding conductors Figure 1 · Connectors must provide a tran- results in an area with a characteristic sition from a round coaxial transmission line impedance that can be much different (usual- to the planar microstrip or stripline structure ly lower) that the system impedance of 50 of a p.c. board. ohms (RF/microwave) or 75 ohms (data or video). An additional challenge is the transition increases the characteristic impedance in the from the round coaxial structure of cables and area where the required solder pad is much their connectors, to the planar stripline or wider than a normal 75-ohm microstrip line. microstrip structure of signal paths on a p.c. Figure 2 illustrates the problem by showing board. The connector shown in Figure 1 the relative widths of the solder pad and demonstrates one approach to solving the microstrip lines on the top metal layer. Figure problem. The connector body is designed to 3 shows how the top metal and the metal of minimize the VSWR “bump” caused by the the next lower layer are modified to create a change from coaxial to planar transmission region with higher characteristic impedance. -

Mfj-1046 Passive Preselector

MFJ-1046 Instruction Manual Passive Preselector MFJ-1046 PASSIVE PRESELECTOR Introduction The MFJ-1046 Passive Preselector is designed to reduce receive overload from strong out of band signals. It contains selective circuits that cover 1.6 to 33 MHz in six steps, providing the greatest selectivity on the lowest frequencies where overload is most common. The MFJ-1046 has two rear panel SO-239 connectors for RF connections and a bypass switch to take the unit in and out of the circuit. Installation Connect the MFJ-1046 Passive Preselector between your antenna and receiver as shown in Figure 1. The Radio connector goes directly to the receiver with a short well shielded lead; the Antenna connector goes to the antenna. Figure 1 WARNING: NEVER connect an amplifier or transmitter to the MFJ-1046 Passive Preselector. Failure to follow this warning may cause MFJ-1046 Passive Preselector or other equipment to be damaged. 1 MFJ-1046 Instruction Manual Passive Preselector Operation With the MFJ-1046 Passive Preselector properly connected, simply turn the Band switch to the desired band and adjust the Tune control for maximum signal level. With the Bypass switch depressed, the MFJ-1046 Passive Preselector becomes active. Adjust the Tune control for maximum signal level. The maximum loss on the desired amateur band is less than 5dB if the correct frequency range is selected. Note: Always use the highest frequency band range that covers the desired band for minimum loss. Typical frequency response is shown in Figure 2. A: Transmission Loss Figure 2 2 MFJ-1046 Instruction Manual Passive Preselector Technical Assistance If you have any problem with this unit first check the appropriate section of this manual. -

Lecture 25 Demodulation and the Superheterodyne Receiver EE445-10

EE447 Lecture 6 Lecture 25 Demodulation and the Superheterodyne Receiver EE445-10 HW7;5-4,5-7,5-13a-d,5-23,5-31 Due next Monday, 29th 1 Figure 4–29 Superheterodyne receiver. m(t) 2 Couch, Digital and Analog Communication Systems, Seventh Edition ©2007 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. 0-13-142492-0 1 EE447 Lecture 6 Synchronous Demodulation s(t) LPF m(t) 2Cos(2πfct) •Only method for DSB-SC, USB-SC, LSB-SC •AM with carrier •Envelope Detection – Input SNR >~10 dB required •Synchronous Detection – (no threshold effect) •Note the 2 on the LO normalizes the output amplitude 3 Figure 4–24 PLL used for coherent detection of AM. 4 Couch, Digital and Analog Communication Systems, Seventh Edition ©2007 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. 0-13-142492-0 2 EE447 Lecture 6 Envelope Detector C • Ac • (1+ a • m(t)) Where C is a constant C • Ac • a • m(t)) 5 Envelope Detector Distortion Hi Frequency m(t) Slope overload IF Frequency Present in Output signal 6 3 EE447 Lecture 6 Superheterodyne Receiver EE445-09 7 8 4 EE447 Lecture 6 9 Super-Heterodyne AM Receiver 10 5 EE447 Lecture 6 Super-Heterodyne AM Receiver 11 RF Filter • Provides Image Rejection fimage=fLO+fif • Reduces amplitude of interfering signals far from the carrier frequency • Reduces the amount of LO signal that radiates from the Antenna stop 2/22 12 6 EE447 Lecture 6 Figure 4–30 Spectra of signals and transfer function of an RF amplifier in a superheterodyne receiver. 13 Couch, Digital and Analog Communication Systems, Seventh Edition ©2007 Pearson Education, Inc. -

Glossary Compiled with Use of Collier, C

Glossary Compiled with use of Collier, C. (Ed.): Applications of Weather Radar Systems, 2nd Ed., John Wiley, Chichester 1996 Rinehard, R.E.: Radar of Meteorologists, 3rd Ed. Rinehart Publishing, Grand Forks, ND 1997 DoC/NOAA: Fed. Met. Handbook No. 11, Doppler Radar Meteorological Observations, Part A-D, DoC, Washington D.C. 1990-1992 ACU Antenna Control Unit. AID converter ADC. Analog-to-digitl;tl converter. The electronic device which converts the radar receiver analog (voltage) signal into a number (or count or quanta). ADAS ARPS Data Analysis System, where ARPS is Advanced Regional Prediction System. Aliasing The process by which frequencies too high to be analyzed with the given sampling interval appear at a frequency less than the Nyquist frequency. Analog Class of devices in which the output varies continuously as a function of the input. Analysis field Best estimate of the state of the atmosphere at a given time, used as the initial conditions for integrating an NWP model forward in time. Anomalous propagation AP. Anaprop, nonstandard atmospheric temperature or moisture gradients will cause all or part of the radar beam to propagate along a nonnormal path. If the beam is refracted downward (superrefraction) sufficiently, it will illuminate the ground and return signals to the radar from distances further than is normally associated with ground targets. 282 Glossary Antenna A transducer between electromagnetic waves radiated through space and electromagnetic waves contained by a transmission line. Antenna gain The measure of effectiveness of a directional antenna as compared to an isotropic radiator, maximum value is called antenna gain by convention. -

Using Ferrite Beads Keep RF out of TV Sets, Telephones, VCR's Burglar Alarms and Other Electronic Equipment

Using Ferrite Beads Keep RF Out of TV Sets, Telephones, VCR's Burglar Alarms and other Electronic Equipment RFI and TVI have been with us for a long time. Now we have microwave ovens, VCR's and many other devices that do wrong things when they pick up RF. There are several ways to tackle the problem but most of them involve opening the affected equipment and adding suppressor capacitors, filters, and other circuit modifications. Unfortunately there is a serious disadvantage associated with this approach. Any modifications made to domestic entertainment equipment can - and often are - blamed for later problems that arise in it. Modifying your own equipment is not so bad, but taking a soldering iron to your neighbor's stereo is risky. An alternative approach is to use ferrite beads to reduce the amount of RF entering the equipment. If the equipment is in a metal box, or even if it's in a plastic box, if RF is prevented from entering the box on the antenna lead, the power cable, the speaker leads, the phono pickup leads, and on any other wires entering the box, it is possible to solve the problem without any modification to the equipment. Ferrite beads just slip over the wires and stop RF from going in. Ferrite beads are made of the same materials as the toroid cores used in broadband transformers but are used at much higher frequencies. For example, ferrite Mix 43 is used for tuned circuits in the frequency range 0.01 to 1 MHz. It is efficient and losses are low.