Kenya: Nutrition Profile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nairobi County

Nairobi County Nairobi County at a glance Nairobi is the Capital City of Kenya and borders Kiambu County to the north west, north and north east, Machakos to the east and south east, Kajiado to the south, south west and west Area: 695 km² Population: 3,138,369 (Male - 51%, Female - 49%) Accountability and Governance The Constitution of Kenya (2010) has provided the opportunity for resources to be transferred to a new level of government at the grassroots. While devolution has created a new reform space for more responsive, equitable, efficient and accountable local service delivery, converting this into actual transformation at the grassroots will depend on the quality of county institutions charged with this responsibility. Since devolution entails the simultaneous transfer of power and resources to an entire new level of government, counties face unique challenges that demand innovative solutions. The EU is therefore working with the Government of Kenya to promote transparency and accountability in the management of county public finances. Sound economic and political governance will allow the residents of all counties to reap the benefits that devolution promises to bring to the people. Sustainable Infrastructure The EU together with its development partners, has committed to continue supporting Kenya in its infrastructure projects with a focus on energy, transport, water and sanitation and housing. This is in line with Vision 2030 (MTPII) and the government’s Big Four agenda. The EU is also supporting the country towards the modernisation its energy infrastructure with a special focus on development of renewable, affordable and reliable energy sources. This support is also targeting access to energy in rural areas in Kenya in order to increase the economic and social development of communities, households, and to spur the creation and growth of energy-based and reliant small enterprises. -

Nairobi-Thika-Transp

FOREWORD I am pleased to introduce this 10-plan year which is a road map on how the Nairobi - Thika Superhighway Transport Corridor (NTTC) is geared to develop. This is the first comprehensive spatial plan covering the NTTC, which is within Ruiru and Juja Sub-Counties and it has been prepared at a time when Kiambu County is grappling with the challenges of tackling rapid urbanisation. I am happy to note that, this plan has been prepared in a participatory manner taking into account the contributions of various stakeholders whose role in the implementation of the proposals is fundamental. Kiambu is the third most urbanised County after Nairobi and Mombasa and has witnessed rapid urbanisation in the few decades with people moving into the County to settle, set business, and undertake other development activities. The NTTC has witnessed rapid urbanisation coupled with high population growth and economic activities in the last ten years since the onset of devolved government and the upgrading of the Nairobi-Thika Highway thus changing the corridor’s character. Due to this rapid growth as a County, we are expected to commit more investments to cope with this expansion. More people need to be accommodated in a suitable environment with ease of movement, adequate physical and social infrastructure and employment opportunities. However, most of this urbanisation is happening with little or no planning intervention as characterised by piecemeal subdivision and land-use conversions. Due to the absence of planning tools like the Plan to guide and manage this rapid urbanisation, the current development in these areas is suffering from uncoordinated growth, land use conflict, inadequate basic infrastructure facilities and services, poor housing, and inefficient public transportation system, amongst other challenges. -

Toxic Site Identification Program in Kenya

Toxic Site Identification Program in Kenya Award: DCI-ENV/2015/371157 Prepared by: Judith St. Fort Prepared for: UNIDO Date: October 2018 Pure Earth 475 Riverside Drive, Suite 860 New York, NY, USA +1 212 647 8330 www.pureearth.org TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS ...............................................................................................................................I LIST OF ANNEXES...................................................................................................................................I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ 1 BACKGROUND ...................................................................................................................................... 2 TOXIC SITE IDENTIFICATION PROGRAM (TSIP) ............................................................................... 3 TSIP TRAINING .............................................................................................................................. 3 IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGY/COORDINATION WITH THE GOVERNMENT ................................ 3 PROGRAM IMPLEMENTATION ACTIVITIES ............................................................................... 4 SUMMARY OF SITES ASSESSED ....................................................................................................... -

The Impact of Measures to Curb COVID-19 on Patient Attendance At

Electronic supplementary material: The online version of this article contains supplementary material. © 2021 The Author(s) Cite as: Gitau T, Kamita M, Muli E, Mweni S, Waithanji R, Mutisya F, Kirira P, Nzioka JoGH © 2021 ISoGH A, Figueroa J, Makokha F. The impact of measures to curb COVID-19 on patient attendance at 10 hospitals in Machakos County, Kenya. J Glob Health 2021;11:05016. The impact of measures to curb COVID-19 on patient attendance at 10 RESEARCH THEME 1: VIEWPOINTS COVID-19 PANDEMIC hospitals in Machakos County, Kenya 1 Tabither Gitau *, Background The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in both direct and indirect impacts Moses Kamita1*, on patients and population health. To better understand the impact of the measures put Elizabeth Muli2, in place by the Kenyan government on health care provision, this project sought to doc- Sharon Mweni3, ument and quantify the impact of the restriction measures on patients’ attendance in Rebeccah Waithanji1, Machakos County. Faith Mutisya3, Methods Hospital attendance at 10 public hospitals were obtained including Machakos Peter Kirira1, Level 5 Hospital (the county referral facility) and one health facility from each of the 9 3 Sub-counties of Machakos County. Data on outpatient and inpatient attendance from No- Ancent Nzioka , vember 2019 to May 2020 were obtained and compared with a similar calendar period Jonine Figueroa4*, from the previous year. Key informant interviews (KIIs), focused group discussions (FGDs) Francis Makokha1* and in-depth interviews were conducted with the hospital management personnel (n = 46), as well as with the patients (n = 453) who missed scheduled clinic appointments at Mach- 1Mount Kenya University, akos Level 5 Hospital to understand the reasons behind the drop in attendance numbers. -

Transition and Reform People’S Peacemaking Perspectives on Kenya’S Post-2008 Political Crisis and Lessons for the Future

REPORT Transition and reform People’s Peacemaking Perspectives on Kenya’s post-2008 political crisis and lessons for the future James Ndung’u and Manasseh Wepundi March 2012 SUDAN Turkana ETHIOPIA Lake Turkana Mandera Marsabit a UGANDA Wajir West Pokot Samburu Isiolo Trans Elgeyo SOMALIA Nzoiaa Marakwet Baringo Bungoma d Uasihin Gishud Busia Kakamega Laikipia Nandi Meru Siaya Vihiga Kisumu d Nyandarua L. Victoria d Tharaka Kerichod d Garissa Nakuru Homa Kirinyaga Bay Nyamira d Embu Kisii Bomet Muranga Migoria d Narok Nairobi d Machakos Kitui Tana River Kajiado Makueni Lamu ³ TANZANIA Kilifi Legend Taita d Hotspots Taveta Indian Ocean a Potential hotspots Mombasa International boundary Kwale a County boundary Shoreline SCALE: 1:4,500,000 Ocean/lakes 075 150 300 Km Prepared by Kenya National Bureau of Statistics_GIS Unit-2009 Census This map is not an authority on delineation of boundaries Transition and reform People’s Peacemaking Perspectives on Kenya’s post-2008 political crisis and lessons for the future James Ndung’u and Manasseh Wepundi SAFERWORLD MARCH 2012 Acknowledgements This report was written by James Ndung’u and Manasseh Wepundi. We wish to thank a number of interviewees and focus group participants for their views and feedback. They include staff from Konrad Adeneur Stiftung, Africa Centre for Open Governance, Movement for Political Accountability, Peace and Development Network Kenya and community representatives from Western, Eastern, Rift Valley, Nyanza, Nairobi, Coast, North Eastern and Central Provinces who participated in focus group discussions. Thanks also go to Bonita Ayuko of Saferworld for organising focus groups and consultative forums in the provinces. -

County Name County Code Location

COUNTY NAME COUNTY CODE LOCATION MOMBASA COUNTY 001 BANDARI COLLEGE KWALE COUNTY 002 KENYA SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT MATUGA KILIFI COUNTY 003 PWANI UNIVERSITY TANA RIVER COUNTY 004 MAU MAU MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL LAMU COUNTY 005 LAMU FORT HALL TAITA TAVETA 006 TAITA ACADEMY GARISSA COUNTY 007 KENYA NATIONAL LIBRARY WAJIR COUNTY 008 RED CROSS HALL MANDERA COUNTY 009 MANDERA ARIDLANDS MARSABIT COUNTY 010 ST. STEPHENS TRAINING CENTRE ISIOLO COUNTY 011 CATHOLIC MISSION HALL, ISIOLO MERU COUNTY 012 MERU SCHOOL THARAKA-NITHI 013 CHIAKARIGA GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL EMBU COUNTY 014 KANGARU GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL KITUI COUNTY 015 MULTIPURPOSE HALL KITUI MACHAKOS COUNTY 016 MACHAKOS TEACHERS TRAINING COLLEGE MAKUENI COUNTY 017 WOTE TECHNICAL TRAINING INSTITUTE NYANDARUA COUNTY 018 ACK CHURCH HALL, OL KALAU TOWN NYERI COUNTY 019 NYERI PRIMARY SCHOOL KIRINYAGA COUNTY 020 ST.MICHAEL GIRLS BOARDING MURANGA COUNTY 021 MURANG'A UNIVERSITY COLLEGE KIAMBU COUNTY 022 KIAMBU INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY TURKANA COUNTY 023 LODWAR YOUTH POLYTECHNIC WEST POKOT COUNTY 024 MTELO HALL KAPENGURIA SAMBURU COUNTY 025 ALLAMANO HALL PASTORAL CENTRE, MARALAL TRANSZOIA COUNTY 026 KITALE MUSEUM UASIN GISHU 027 ELDORET POLYTECHNIC ELGEYO MARAKWET 028 IEBC CONSTITUENCY OFFICE - ITEN NANDI COUNTY 029 KAPSABET BOYS HIGH SCHOOL BARINGO COUNTY 030 KENYA SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT, KABARNET LAIKIPIA COUNTY 031 NANYUKI HIGH SCHOOL NAKURU COUNTY 032 NAKURU HIGH SCHOOL NAROK COUNTY 033 MAASAI MARA UNIVERSITY KAJIADO COUNTY 034 MASAI TECHNICAL TRAINING INSTITUTE KERICHO COUNTY 035 KERICHO TEA SEC. SCHOOL -

County Integrated Development Plan (Cidp) 2018-2022

COUNTY INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN (CIDP) 2018-2022 WORKING DRAFT NOVEMBER, 2017 Nairobi County Integrated Development Plan, 2018 Page ii COUNTY VISION AND MISSION VISION “The city of choice to Invest, Work and live in” MISSION To provide affordable, accessible and sustainable quality service, enhancing community participation and creating a secure climate for political, social and economic development through the commitment of a motivated and dedicated team. Nairobi County Integrated Development Plan, 2018 Page iii Nairobi County Integrated Development Plan, 2018 Page iv FOREWORD Nairobi County Integrated Development Plan, 2018 Page v Nairobi County Integrated Development Plan, 2018 Page vi TABLE OF CONTENTS COUNTY VISION AND MISSION ............................................................................................. iii FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................. v LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... xiii LIST OF MAPS/FIGURES ......................................................................................................... xiii LIST OF PLATES ......................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .................................................................................... xiv GLOSSARY OF COMMONLY USED TERMS ..................................................................... -

GIS, Remote Sensing, Spatial Urban Growth, Nairobi Metropolitan Region, Sustainable Development

American Journal of Geographic Information System 2017, 6(2): 64-82 DOI: 10.5923/j.ajgis.20170602.03 Spatial Monitoring of Urban Growth Using GIS and Remote Sensing: A Case Study of Nairobi Metropolitan Area, Kenya Monica Machuma Katyambo*, Moses Murimi Ngigi Institute of Geomatics, GIS and Remote Sensing, Dedan Kimathi University of Technology, Nyeri, Kenya Abstract Nairobi city expanded spatially leading to the formation of the 32,514 km2 Nairobi Metropolitan Area. The region faces rapid urbanization challenges and lacks reliable data for urban planning. This study is aimed at monitoring the urban land cover using GIS and Remote Sensing techniques. Three different land cover maps produced at ten year epochs between 1995 and 2015 were used to evaluate and analyse urban growth visually and quantitatively. Spatial metrics indices and the Annual Urban Spatial Expansion Index were employed in the quantitative analyses. Urban land cover increased from 408.99 km2 to 763.79 km2 and to 2,187.82 km2 with annual growth rates of 8.4% and 17.2% in the two study period epochs. The areas had annual spatial expansion indices of 4.58% and 6.32% respectively in the periods 1995- 2000 and 2000-2015. Radial-axial expansion of built-up areas along transport routes led to the expansion of urban areas into agricultural and forest land. The region’s spatial plan forecasted an urban land cover of 1,717.72km2 by the year 2030, yet by the year 2015, the urban area was 2,187.82 km2. These growth characteristics will have an effect on the location of the proposed Cyber city, Knowledge-cum-Health city and the Aerotropolis, as proposed in the spatial planning concept of the NMR. -

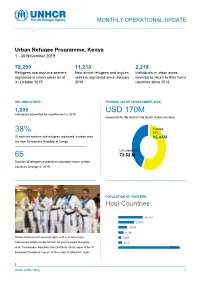

Urban Refugee Programme Operational Update

MONTHLY OPERATIONAL UPDATE Urban Refugee Programme, Kenya 1 - 30 November 2019 7 8,299 11,210 2,218 Refugees and asylums seekers New arrival refugees and asylum Individuals in urban areas registered in urban areas as at seekers registered since January assisted to return to their home 31 October 2019 2019. countries since 2014. KEY INDICATORS FUNDING (AS OF 09 DECEMBER 2019) 1,200 USD 170M individuals submitted for resettlement in 2019. requested for the Somali and South Sudan situation Funded 38% 53% Of asylums seekers and refugees registered in urban area 96.44M are from Democratic Republic of Congo Unfunded 43% 65 73.52 M Number of refugees assisted to voluntarily return to their countries of origin in 2019. POPULATION OF CONCERN Host Countries 30, 470 20,075 10,995 8,198 Gaston Nsazumukiza (second right), a 27 year old refugee 3,820 Taekwondo athlete stands tall with his bronze medal alongside 4,741 other Taekwondo champions from Southern Africa region at the 4th 78,299 Botswana Presidents Cup on 16 November © UNHCR/C.Opile t www.unhcr.org 1 OPERATIONAL UPDATE NAIROBI, KENYA / 30 September 2019 HIGHLIGHTS ▪ UNHCR conducted a joint mission with the Ethiopian Embassy to Kakuma Refugee camp. The delegation met with Ethiopian refugees who have expressed interest in voluntary repatriation. Plans are underway to facilitate repatriation of 85 Ethiopians from Kakuma camp. ▪ UNHCR in partnership with the National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (NGLHRC) and the Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC) conducted a two-day training for magistrates and judges from the Coastal region. -

Figure1: the Map of Kenya Showing 47 Counties (Colored) and 295 Sub-Counties (Numbered)

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Global Health Additional file 1: The county and sub counties of Kenya Figure1: The map of Kenya showing 47 counties (colored) and 295 sub-counties (numbered). The extents of major lakes and the Indian Ocean are shown in light blue. The names of the counties and sub- counties corresponding to the shown numbers below the maps. List of Counties (bold) and their respective sub county (numbered) as presented in Figure 1 1. Baringo county: Baringo Central [1], Baringo North [2], Baringo South [3], Eldama Ravine [4], Mogotio [5], Tiaty [6] 2. Bomet county: Bomet Central [7], Bomet East [8], Chepalungu [9], Konoin [10], Sotik [11] 3. Bungoma county: Bumula [12], Kabuchai [13], Kanduyi [14], Kimilili [15], Mt Elgon [16], Sirisia [17], Tongaren [18], Webuye East [19], Webuye West [20] 4. Busia county: Budalangi [21], Butula [22], Funyula [23], Matayos [24], Nambale [25], Teso North [26], Teso South [27] 5. Elgeyo Marakwet county: Keiyo North [28], Keiyo South [29], Marakwet East [30], Marakwet West [31] 6. Embu county: Manyatta [32], Mbeere North [33], Mbeere South [34], Runyenjes [35] Macharia PM, et al. BMJ Global Health 2020; 5:e003014. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003014 BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Global Health 7. Garissa: Balambala [36], Dadaab [37], Dujis [38], Fafi [39], Ijara [40], Lagdera [41] 8. -

The Nature, Challenges and Consequences of Urban Youth Unemployment: a Case of Nairobi City, Kenya

Universal Journal of Educational Research 2(7): 495-503, 2014 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/ujer.2014.020701 The Nature, Challenges and Consequences of Urban Youth Unemployment: A Case of Nairobi City, Kenya Bernard Munyao Muiya Department of Sociology, Kenyatta University, Kenya *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Copyright © 2014 Horizon Research Publishing All rights reserved. Abstract Globally, decline in employment has affected issue in society. The International Labour Organization [26] the youth more compared to other cohorts with youth in estimates that the percentage of young women and men who developing countries being particularly hard hit. There have are unemployed throughout the world represents roughly been various interventions by the Kenyan government to two-fifths of all unemployed persons [26]. In general, young address the challenge of youth employment through human people are two to three times more likely than adults to be capital development like the Youth Enterprise Development unemployed. Fund (YEFD). Despite this, youth unemployment still A 2010 study by the ILO indicates that the share of youth remains a big problem making youth vulnerable to crime and who are employed in the youth population saw a decrease social unrest. This paper investigated the nature, challenges from 47.9 to 44.7 per cent between 1998 and 2008 [26, 37]. and consequences of urban youth unemployment in Nairobi, This kind of a scenario does not portend well for global Kenya. The results of this paper were obtained through a economies and therefore stringent measures should be put in survey done in Mathare informal settlement July 2013. -

Understanding the Socioeconomic Conditions of the Stateless Shona Community in Kenya Results from the 2019 Socioeconomic Survey

Understanding the Socioeconomic Conditions of the Stateless Shona Community in Kenya Results from the 2019 Socioeconomic Survey 2020 10183_Shona_CVR.indd 3 12/14/20 11:20 AM Understanding the Socioeconomic Conditions of the Stateless Shona Community in Kenya Results from the 2019 Socioeconomic Survey 10183_Shona Report.indd 1 2/8/21 1:15 PM Cover photo: © Rose Ogola, UNHCR. 10183_Shona Report.indd 2 2/8/21 1:15 PM Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . vi LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS . vii FOREWORDS . viii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . x BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES . 1 I. Statelessness in Kenya ............................................................... 2 FINDINGS . 7 I. Consumption and Poverty ............................................................ 7 II. Demographic Profile . 8 III. Access to Basic Services ............................................................. 11 i. Housing.......................................................................... 11 ii. Water and sanitation .............................................................. 15 iii. Energy........................................................................... 17 iv. Education ........................................................................ 18 IV. Employment and Livelihoods ......................................................... 24 V. County Trends ...................................................................... 29 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS . 30 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 32 APPENDIXES . 34 Appendix A. Locations of Interviewed Shona Households in Kenya ............................