Vision and Transformation: the Buddha's Eightfold Path Week 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Stream of Blessings: Ordained Buddhist Women in Britain

In the Stream of Blessings: Ordained Buddhist Women in Britain Caroline Starkey Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Philosophy, Religion, and History of Science December 2014 2 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement ©2014 The University of Leeds and Caroline Starkey The right of Caroline Starkey to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 3 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the support, guidance, and advice of a number of people and institutions. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude to the Arts and Humanities Research Council, the University of Leeds, and to the Spalding Trust, each of whom provided vital funding. The School of Philosophy, Religion, and History of Science at the University of Leeds was extremely supportive, providing me with space to work, funding for conferences, and a collegiate atmosphere. A very special and truly heartfelt thank you is due to both of my academic supervisors – Professor Kim Knott and Dr Emma Tomalin. I am grateful for their attention to detail, their thought-provoking questions, and the concern that they showed both for my research and for me as a researcher. -

Buddhist Meditation Centre 2018 As Our Archive Photos in This Programme Show, Vajraloka Has Come a Long Way

Buddhist Meditation Centre 2018 As our archive photos in this programme show, Vajraloka has come a long way. For over three decades now, Vajraloka’s team and guest retreat leaders have been contributing to Triratna’s developing lineage of meditation teaching – in particular, offering a practical, hands-on vision of ‘what’s next’ for experienced meditators. This vision goes deeply into all areas of Triratna’s system of meditation and supports all areas of Dharma practice. Yet, Vajraloka wasn’t set up to offer meditation teaching. For the first half decade or so, the resident team at Vajraloka followed a daily programme of meditation and work which others would simply join in for a week or more. The team were also exploring their own meditation deeply, and studying traditional meditation texts such as Dhyana for Beginners by Chih-I, together with Sangharakshita’s commentaries and seminars. Before long, it became clear to the resident team that practical input could greatly benefit retreatants’ practice. So the centre morphed into offering themed retreats on the main areas of meditation practice in Triratna. The current team owe a huge amount to those who went before, both for developing that lineage of helpful meditation teaching and for converting the dilapidated farm buildings into a well-appointed retreat centre. The improvement of our facilities continues – there are new projects in the pipeline for the foreseeable future, which we hope you’ll like and support. But above all, we continue to explore and offer what genuinely helps people consolidate and take their practice deeper. We have found that deepening of body awareness enhances all our practices – mindfulness, metta and just sitting included – providing a strong, positive basis for insight (spiritual death) – inquiring into ‘how things really are’. -

Addressing Ethical Issues in Triratna

ADDRESSING ETHICAL ISSUES IN TRIRATNA A REPORT ON THE WORK OF THE ADHISTHANA KULA AUGUST 2020 ADDRESSING ETHICAL ISSUES IN TRIRATNA For many years, ethical issues from Triratna’s past have afected the individuals who were involved and the Triratna Buddhist Order and Community as a whole, and a number of people have come forward with accounts of the sufering they experienced within Triratna. Some of these issues involved the sexual behaviour of Sangharakshita, Triratna’s founder. The task of the Adhisthana Kula was to address these issues honestly. We investigated what had happened, inviting people to share their experiences, especially those who were directly afected; and we worked with others to create fresh structures that could address past difculties and help prevent future problems. As the Adhisthana Kula concludes its work in 2020, this document shares its fndings and reports on progress. For all our eforts, we wish to acknowledge the wounds that have not yet healed, the stories that have not yet been told and the pain that has not yet been recognised. This is a report on unfnished business, and we suggest how this work can be taken forward in the future. ADDRESSING ETHICAL ISSUES IN TRIRATNA / 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCING THE REPORT A covering letter from the Kula, introducing and summarising the report. The report is divided into six main sections and also includes a suggestion for next steps, and a list of documents and resources relevant to the issues addressed here. 1 / APOLOGY AND REGRET Wanting to express deeply-felt sadness and regret at sufering that has resulted from involvement in Triratna and recognising the need for a clear statement representing Triratna’s current position, the Adhisthana Kula issued a Message of Apology and Regret. -

Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels Handbook Version

Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels Study material for your retreat at Tiratanaloka Page 1 of 43 Edited by Vandananjyoti, Version 2:1, July 2020 Table of Contents Introduction to the Handbook Study Area 1. Centrality of Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels Study Area 2. Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels Study Area 3. Opening of the Dharma Eye and Stream Entry Study Area 4. Going Forth Study Area 5. The Altruistic Dimension of Going for Refuge and Joining the Order Page 2 of 43 Edited by Vandananjyoti, Version 2:1, July 2020 Introduction to the Handbook The purpose of this handbook is to give you the opportunity to look in depth at the material that we will be studying on the Going for Refuge to the Three Jewels retreat at Tiratanaloka. In this handbook we give you material to study for each area we’ll be studying on the retreat. We will also have some talks on the retreat itself where the team will bring out their own personal reflections on the topics covered. As well as the study material in this handbook, it would be helpful if you could read Sangharakshita’s book ‘The History of My Going for Refuge’. You can buy this from Windhorse Publications. There is also some optional extra study material at the beginning of each section. Some of the optional material is in the form of talks that can be downloaded from the Free Buddhist Audio website at www.freebuddhistaudio.com. These aren’t by any means exhaustive - Free Buddhist Audio is growing and changing all the time so you may find other material equally relevant! For example, at the time of writing, Vessantara has just completed a series of talks called ‘Aspects of Going for Refuge’ (2016) at Cambridge Buddhist Centre. -

Triratna Festival Dates 2016 – 2025 CE

Triratna Festival Dates 2016 – 2025 CE CE Year Buddha Day Dharma Day Padmasambhava Sangha Day Day 2016 21 May 19 July 10 September 14 November 2017 10 May 9 July 29 September 4 November 2018 29 May 27 July 18 September 23 November 2019 18 May 16 July 7 October 12 November 2020 7 May 5 July 26 September 30 November 2021 26 May 24 July 16 September 19 November 2022 16 May 13 July 4 October 8 November 2023 5 May 3 July 24 September 27 November 2024 23 May 21 July 12 September 15 November 2025 12 May 10 July 30 September 5 November Fixed date festivals (solar calendar): Parinirvana Day 15 February Triratna Sangha Day 6 April (the anniversary of the founding of the FWBO in 1967) - the 50thanniversary of the Triratna Buddhist Community is in 2017 Triratna Order Day 7 April (the anniversary of the founding of the WBO in 1968) – the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Triratna Buddhist Order is in 2018 Sangharakshita’s birthday 26 August (b. 1925) The lunar calendar festivals are calculated according to the first full moon (in the UK) of May, July, and November. Padmasambhava Day is calculated according to the tenth day of the lunar month starting in September. CE years are given as there is no general agreement between the different traditions on the counting of Buddhist years, but in 1957 the 2500th Buddha Jayanti was celebrated internationally and we therefore calculate the Buddhist year by adding 543 to the CE year. There may be some variation from (and between) Indian, Burmese, Sri Lankan, and Tibetan (etc) festival dates, because their calendars vary and some are not fixed more than a couple of years in advance, and because the full moon sometimes occurs in Asia the day after the UK because of the time difference. -

Going Deeper Meditation Morning Going for Refuge

GOING DEEPER MEDITATION MORNING GOING FOR REFUGE GOING FOR REFUGE AND MEDITATION • The centrality of going for refuge is one of the six distinctive emphases of Triratna. • This was drawn out by Bhante as the unifying principle of all Buddhist traditions o All Buddhist traditions are rooted in the person, teaching, and community of followers of the Buddha • Going for refuge makes meditation distinctively Buddhist rather than secular or religious in a theistic sense • So what does it mean to go for refuge in meditation? How do we make that more explicit TO THE SANGHA • We can draw on the support of meditating amongst brothers and sisters in the sangha who are also going for refuge in the same sense that we are • As a refuge, the sangha is the company of Bodhisatvas and arahants – we don’t go for refuge to contempo- rary individuals – such as the public preceptors or Bhante. In Tibetan Buddhism practitioners would take ref- uge in their lama (personal guru). This isn’t something Bhante wanted to replicate. o So, taking the sangha refuge to be the bodhisattvas and arahants, these embody / symbolise particu- lar facets of enlightened awareness. We may have a response to a particular bodhisattva for exam- ple – in which case that figure will hold for us an authentic quality of enlightened awareness: com- passion, energy, clarity, or wisdom for example. This figure could be our focus rather than the Bud- dha Shakyamuni – and the comments on going for refuge to the Buddha given below apply. TO THE DHARMA To go for refuge to the dharma is to enter deeply into the sutra treasures whereby our wisdom may grow as deep as the ocean. -

The Wheel of Life

Triratna Dharma Training Course for Mitras – Foundation Year Part 4: Exploring Buddhist Practice – Wisdom Week 3: The Wheel of Life Text purpose-written by Vadanya Introduction – reactive and creative conditionality In the last session we saw that conditionality is the central concept that the Buddha used to communicate his vision of reality. Conditionality can work in two ways, which Sangharakshita has called the reactive and creative modes. In the reactive mode, things go round in circles, and nothing new ever happens. In the creative mode, on the other hand, each event builds on the one before it, unfolding ever more new possibilities. The reactive mode When we are in the reactive mode we behave like machines, doing what our past conditioning has programmed us to do. We see the cake, and reach for it. A comment annoys us, and we snap. We feel bored, so we turn on the TV. The world pushes one of our buttons, and we respond, like a machine, in our usual way. Each time we react automatically in this way we strengthen our old pattern. Next time the button is pushed we are a little more likely to do the same old thing again, and we find it a little more difficult to do anything else. The classic example of this is an addictive pattern like smoking, but the same thing is true of any behaviour, of body, speech or mind. So in the reactive mode we go round in circles, deepening our old ruts. The circles we go round in can be simple, like the smoker’s endless round of craving and cigarettes. -

Bodh Gayā in the Cultural Memory of Thailand

Eszter Jakab REMEMBERING ENLIGHTENMENT: BODH GAYĀ IN THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF THAILAND MA Thesis in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Central European University CEU eTD Collection Budapest June 2020 REMEMBERING ENLIGHTENMENT: BODH GAYĀ IN THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF THAILAND by Eszter Jakab (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection Budapest Month YYYY REMEMBERING ENLIGHTENMENT: BODH GAYĀ IN THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF THAILAND by Eszter Jakab (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest June 2020 REMEMBERING ENLIGHTENMENT: BODH GAYĀ IN THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF THAILAND by Eszter Jakab (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European -

Reading the History of a Tibetan Mahakala Painting: the Nyingma Chod Mandala of Legs Ldan Nagpo Aghora in the Roy Al Ontario Museum

READING THE HISTORY OF A TIBETAN MAHAKALA PAINTING: THE NYINGMA CHOD MANDALA OF LEGS LDAN NAGPO AGHORA IN THE ROY AL ONTARIO MUSEUM A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sarah Aoife Richardson, B.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2006 Master's Examination Committee: Dr. John C. Huntington edby Dr. Susan Huntington dvisor Graduate Program in History of Art ABSTRACT This thesis presents a detailed study of a large Tibetan painting in the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) that was collected in 1921 by an Irish fur trader named George Crofts. The painting represents a mandala, a Buddhist meditational diagram, centered on a fierce protector, or dharmapala, known as Mahakala or “Great Black Time” in Sanskrit. The more specific Tibetan form depicted, called Legs Idan Nagpo Aghora, or the “Excellent Black One who is Not Terrible,” is ironically named since the deity is himself very wrathful, as indicated by his bared fangs, bulging red eyes, and flaming hair. His surrounding mandala includes over 100 subsidiary figures, many of whom are indeed as terrifying in appearance as the central figure. There are three primary parts to this study. First, I discuss how the painting came to be in the museum, including the roles played by George Croft s, the collector and Charles Trick Currelly, the museum’s director, and the historical, political, and economic factors that brought about the ROM Himalayan collection. Through this historical focus, it can be seen that the painting is in fact part of a fascinating museological story, revealing details of the formation of the museum’s Asian collections during the tumultuous early Republican era in China. -

Seven Papers by Subhuti with Sangharakshita

SEVEN PAPERS by SANGHARAKSHITA and SUBHUTI 2 SEVEN PAPERS May the merit gained In my acting thus Go to the alleviation of the suffering of all beings. My personality throughout my existences, My possessions, And my merit in all three ways, I give up without regard to myself For the benefit of all beings. Just as the earth and other elements Are serviceable in many ways To the infinite number of beings Inhabiting limitless space; So may I become That which maintains all beings Situated throughout space, So long as all have not attained To peace. SEVEN PAPERS 3 SEVEN PAPERS BY SANGHARAKSHITA AND SUBHUTI 2ND EDITION (2.01) with thanks to: Sangharakshita and Subhuti, for the talks and papers Lokabandhu, for compiling this collection lulu.com, the printers An A5 format suitable for iPads is available from Lulu; for a Kindle version please contact Lokabandhu. This is a not-for-profit project, the book being sold at the per-copy printing price. 4 SEVEN PAPERS Contents Introduction 8 What is the Western Buddhist Order? 9 Revering and Relying upon the Dharma 39 Re-Imagining The Buddha 69 Buddhophany 123 Initiation into a New Life: the Ordination Ceremony in Sangharakshita's System oF Spiritual Practice 127 'A supra-personal force or energy working through me': The Triratna Buddhist Community and the Stream of the Dharma 151 The Dharma Revolution and the New Society 205 A Buddhist Manifesto: the Principles oF the Triratna Buddhist Community 233 Index 265 Notes 272 SEVEN PAPERS 5 6 SEVEN PAPERS SEVEN PAPERS 7 Introduction This book presents a collection of seven recent papers by either Sangharakshita or Subhuti, or both working together. -

Compassion and Emptiness in Early Buddhist Meditation Provides a Window Into the Depth and Beauty of the Buddha’S Liberating Teachings

‘This book is the result of rigorous textual scholarship that can be valued not only by the academic community, but also by Buddhist practitioners. This book serves as an important bridge between those who wish to learn about Buddhist thought and practice and those who wish to learn from it.... As a monk engaging himself in Buddhist meditation as well as a professor applying a historical-critical methodology, Bhikkhu Anālayo is well positioned to bridge these two com munities who both seek to deepen their understanding of these texts.’ – from the Foreword, 17th Karmapa Ogyen Trinley Dorje ‘In this study, Venerable Anālayo Bhikkhu brings a meticulous textual analysis of Pali texts, the Chinese Agamas and related material from Sanskrit and Tibetan to the foundational topics of compassion and emptiness. While his analysis is grounded in a scholarly approach, he has written this study as a helpful guide for meditation practice. The topics of compassion and emptiness are often associated with Tibetan Buddhism but here Venerable Anālayo makes clear their importance in the early Pali texts and the original schools.’ – Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo ‘This is an intriguing and delightful book that presents these topics from the viewpoint of the early suttas as well as from other perspectives, and grounds them in both theory and meditative practice.’ – Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron ‘A gift of visionary scholarship and practice. Anālayo holds a lamp to illuminate how the earliest teachings wed the great heart of compassion and the liberating heart of emptiness and invites us to join in this profound training.’ – Jack Kornfield ‘Arising from the author’s long-term, dedicated practice and study, Compassion and Emptiness in Early Buddhist Meditation provides a window into the depth and beauty of the Buddha’s liberating teachings. -

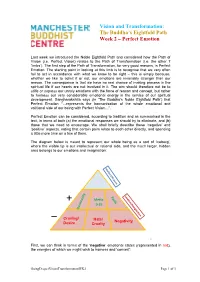

Vision and Transformation: the Buddha's Eightfold Path Week 2 – Perfect Emotion

Vision and Transformation: The Buddha’s Eightfold Path Week 2 – Perfect Emotion Last week we introduced the Noble Eightfold Path and considered how the Path of Vision (i.e. Perfect Vision) relates to the Path of Transformation (i.e. the other 7 ‘limbs’). The first step of the Path of Transformation, for very good reasons, is Perfect Emotion. The starting point in looking at this limb is to recognise that we very often fail to act in accordance with what we know to be right – this is simply because, whether we like to admit it or not, our emotions are invariably stronger than our reason. The consequence is that we have no real chance of making process in the spiritual life if our hearts are not involved in it. The aim should therefore not be to stifle or supress our unruly emotions with the force of reason and concept, but rather to harness our very considerable emotional energy in the service of our spiritual development. Sangharakshita says (in ‘The Buddha’s Noble Eightfold Path’) that Perfect Emotion “…represents the harmonisation of the whole emotional and volitional side of our being with Perfect Vision…”. Perfect Emotion can be considered, according to tradition and as summarised in the text, in terms of both (a) the emotional responses we should try to eliminate, and (b) those that we need to encourage. We shall briefly describe these ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ aspects, noting that certain pairs relate to each other directly, and spending a little more time on a few of them. The diagram below is meant to represent our whole being as a sort of ‘iceberg’, where the visible tip is our intellectual or rational side, and the much larger, hidden area belongs to our emotions and imagination: + Metta (+3) _ Craving/ Hate/ Negativity Desire Cruelty 18 First, we can think in terms of the ‘negative’ emotional states (represented in red), the energies of which we might wish to harness and ‘convert’: GoingDeeperVisionTransformationWK2 Page 1 of 3 1.