CAPITAL INVESTMENT

Capital Investment (Capital Budgeting) involves the allocation of large amounts of resources in long-term investments.

Examples: => Replacement of Equipment => Expansion of Existing Product Lines => Development of New Product Lines => Intangibles: => Research & Development => Patents => Advertising campaigns

Success: Texas Instruments - semiconductor in 1950s and 1960s; microchip in 1970s

Microsoft - Bought Quick and Dirty Operating System for $20,000

Failure: Ford Edsel (Loss of $250 million in 1957-59, or approximately $1.6 billion today)

Once the Investment is made, it is almost impossible to back out. Unlike a surplus of inventory which can be quickly corrected, an unutilized refinery just sits vacant.

The firm's existence is a series of capital investment decisions that are necessary for the company to grow, remain competitive, etc.

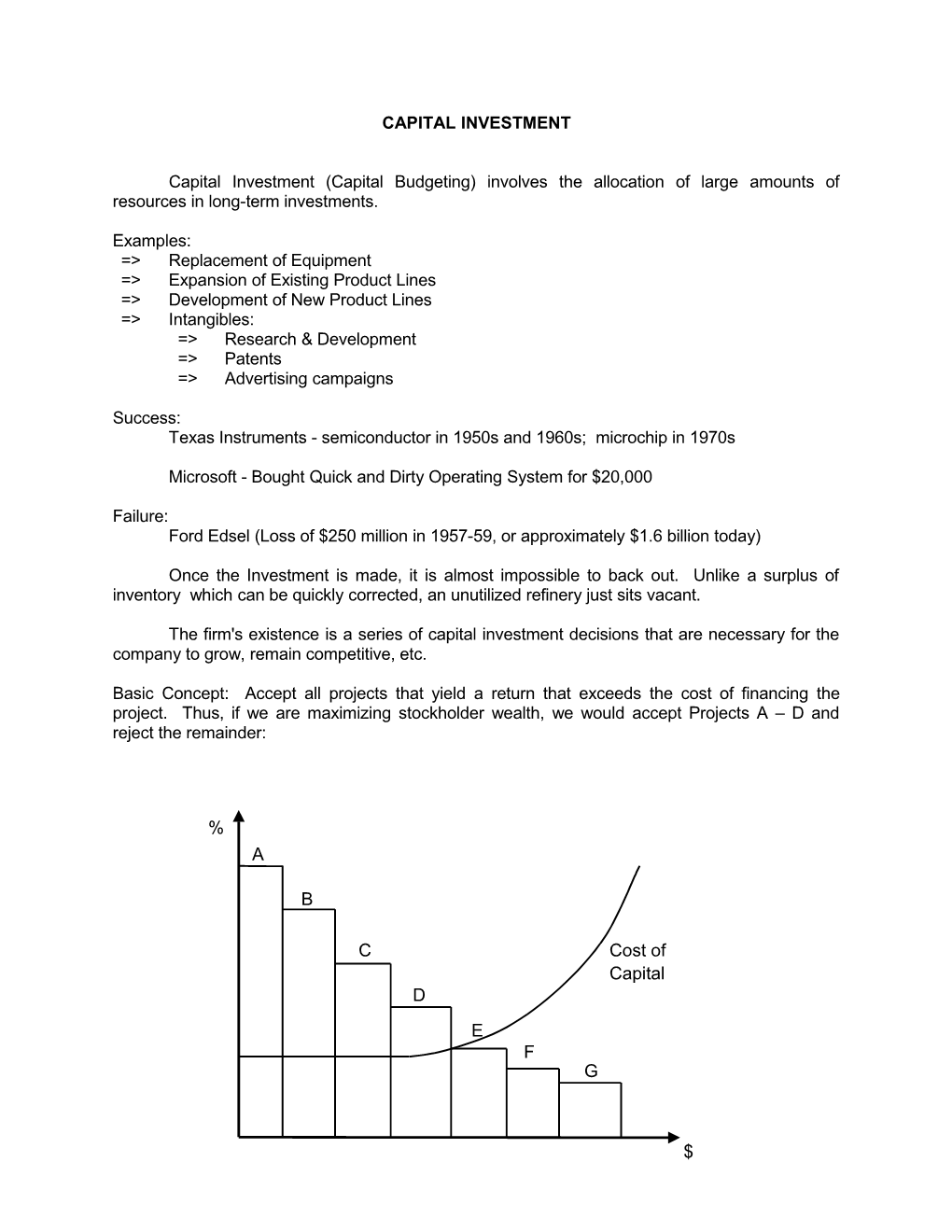

Basic Concept: Accept all projects that yield a return that exceeds the cost of financing the project. Thus, if we are maximizing stockholder wealth, we would accept Projects A – D and reject the remainder:

% A

B

C Cost of Capital D E F G

$ Numerous investment alternatives exist. We need a means of ranking the projects from best to worst in order to select those that are most valuable to the firm; i.e., a means of evaluating and ranking proposals.

The primary concern in the investment decision regards cash flows:

=> Incremental Revenues => Incremental Costs => Taxes => Depreciation considerations => Investment in Working Capital => Cost Savings

Any cash inflow or outflow.

EVALUATION TECHNIQUES

A. Payback Period

Proj. A Proj. B ------Year 0 (3,000) (3,000) Year 1 1,000 2,000 Year 2 2,000 1,000 Year 3 3,000 4,000

Payback = 2 years Payback = 2 years

Both projects have a payback of two years, so the payback method indicates that the two projects are equally desirable.

Problems:

1) Ignores the Time Value of Money

2) Ignores cash flows beyond the payback period

Project B returns $1,000 a year earlier than Project A and also returns an additional $1,000 in the last year.

Present Value Payback, which utilizes the present value of each year's cash flow, overcomes the first problem, but not the second.

B) Net Present Value (NPV)

We need a methodology that takes into account all of the cash flows as well as the time value of money. Net Present Value is one such technique: NPV = PV of Cash Inflows - PV of Cash Outflows Required Rate of Return = 10%

0 1 2 3

(4,000) 1,000 2,000 3,000

0.9091 909 0.8264 1,653 0.7513 2,254

NPV @ 10% = 816

NPV represents the increase in the value of the firm that occurs by accepting the project. In other words, it represents the amount by which the value of the project exceeds its cost.

Proof:

Year 0 Investment 4,000 Cash Flow - Year 1 1,000 Return of Investment (600) Less: Interest (400) (10%*$4,000) ------Year 1 Investment 3,400 Return of Investment 600 Return of Investment (1,660) ------Cash Flow - Year 2 2,000 Year 2 Investment 1,740 Less: Interest (340) (10%*$3,400) Return of Investment (2,826) ------Return of Investment 1,660 Surplus Return (1,086) PVIF10%,3 0.7513 Cash Flow - Year 3 3,000 ------Less: Interest (174) (10%*$1,740) Present Value 816 ------Return of Investment 2,826

The problem with NPV is that there is no consideration of cost, or what is referred to as size disparity.

Proj. A Proj. B ------Present Value of Inflows 1,050 125 Cost (1,000) (100) ------Net Present Value 50 25 If these are mutually exclusive projects (i.e., choose one or the other, but not both), the NPV criterion says to choose Project A. While Project A increases the value of the firm by twice the amount of Project B, it costs ten times as much. The NPV does not indicate how efficiently money has been invested.

Capital Rationing - the allocation of a scarce resource, in this case money.

C) Profitability Index (PI) (or Benefit-Cost Ratio) - a measure of efficiency of investment

PV of Inflows Profitability Index PV of Outflows

PIA = 1.05 PIB = 1.25

The interpretation of PI is that of the amount of money in today's dollar terms that you get per dollar of investment. This indicates how efficiently you have invested money.

D) Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

Another measure of the efficiency of investment is the Internal Rate of Return. When someone asks what rate of return an investment is earning, they mean the Internal Rate of Return. The IRR can be defined as

PV of Inflows @ IRR = PV of Outflows @ IRR or NPV @ IRR = 0

This is the actual rate of interest that is being earned on the investment. While the present value and annuity tables can be used in certain cases, the more general situation of uneven cash flows requires that the IRR be found by trial and error.

From the previous example, it is clear that more than 10% is being earned, since the NPV is $816.

Try 20%

NPV @ 20% = 1,000*(.8333) + 2,000*(.6944) + 3,000*(.5787) - 4,000

= 3,958 - 4,000 = (42)

Interpolating provides an estimate:

10% 816 Z 816 10% IRR 0 858

20% (42)

Z 816 10% 858 Z = 9.51% +10.00 IRR = 19.51%

Year 0 Investment 4,000 Cash Flow -- Year 1 1,000 Return of Investment (220) Less: Interest (780) (19.5% * $4,000) Year 1 Investment 3,780 Return of Investment 220 Return of Investment (1,262) Year 2 Investment 2,518 Cash Flow -- Year 2 2,000 Return of Investment 2,509 Less: Interest (738) (19.5% * $3,780) Surplus Return 9 Return of Investment 1,262 PVIF10%,3 0.7513 Present Value (7) Cash Flow -- Year 3 3,000 Less: Interest (491) (19.5% * $2,518) Return of Investment 2,509

Hence, it is the rate of interest earned on the funds that remain invested within the project. This is the economic interpretation of the mathematical solution. Note that the "true" IRR is 19.44%. The error occurs because interpolation assumes linearity of a non-linear function.

Year 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 NPV @ 10% PI @ 10% IRR Project A (15,000) 10,000 10,000 0 2,355 1.16 21.5% Project B (48,000) 30,000 30,000 0 4,066 1.08 16.3%

Which project is better? The major difference is the costs of the projects.

Year 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 NPV @ 10% PI @ 10% IRR Project C (10,000) 8,000 5,600 0 1,901 1.19 24.9% Project D (10,000) 0 0 17,000 2,772 1.28 19.3%

Which project is better? The major difference is the timing of the cash flows.

Note that all three measures agree as to whether a project is acceptable or not. The conflict is in the ranking of the investment proposals.

Note also that the Profitability Index, a measure of efficiency of investment, does not always agree with IRR in terms of which is the most efficient use of funds.

III) THE REINVESTMENT ASSUMPTION

Consider the following two projects, their NPVs, PIs, and IRRs. Project X Year 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Cash Flows (886) 100 100 1,100

NPV @ 10% = 114 PI @ 10% = 1.13 IRR = 15.0%

Project Y Year 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Cash Flows (886) 900 150 55

NPV @ 10% = 97 PI @ 10% = 1.11 IRR = 20.0%

Most academicians claim that the conflict is a consequence of the reinvestment assumption. Net Present Value and Profitability Index assume reinvestment at the discount rate. Internal Rate of Return can be thought of as a special case of NPV (when it equals zero). Hence, it assumes reinvestment at the IRR.

Realistically, investments are made to maximize future wealth. Present value (discounted cash flow techniques) are used since we know the value of a dollar today. The reinvestment assumption is invoked in order to make the future value (terminal value) rankings consistent with the present value rankings. To see this, let's reinvest the cash flows of Projects X and Y at the discount rate of 10%.

Project X Year 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Cash Flows (886) 100 100 1,100 1.21 121 1.10 110 Terminal Value = 1,331

Project Y Year 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Cash Flows (886) 900 150 55 1.21 1,089 1.10 165 Terminal Value = 1,309

Since the costs are the same, the terminal values are both relative to the same size of investment. The $1,331 terminal value of Project X represents a 14.53% rate of return on an investment of $886 over three years while the $1,309 terminal value of Project Y is a 13.89% return on the initial investment. The difference in the terminal values of $22 has a present value of $17 which is the same as the difference in NPVs of the two projects (114 - 97 = 17). Thus, the terminal value rankings are consistent with the NPV and PI rankings that indicate Project X is superior to Project Y. Similarly, if the cash flows of each project are reinvested at their respective IRRs, the following is obtained:

Project X Year 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Cash Flows (886) 100 100 1,100 1.3223 132 1.1499 115 Terminal Value = 1,347

Project Y Year 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Cash Flows (886) 900 150 55 1.4400 1,296 1.2000 180 Terminal Value = 1,531

Since the costs are identical, it is clear that Project Y is better since it maximizes future wealth, and agrees with the rankings of the IRRs. Moreover, the terminal value of $1,347 of Project X represents a 15% return on the cost of the project, while the $1,531 terminal value of Project Y is a 20% return on the investment in Project Y.

IV. RELEVANT CASH FLOWS

A. Incremental Cash Flows

The relevant cash flows for investment analysis is the change in the cash flows that would occur by accepting a proposal, or what is referred to by the term incremental cash flows. An opportunity cost is a cash flow given up as a consequence of a decision, and is generally defined as the next-best-alternative. Since an opportunity cost is a change in cash flow, it is relevant to the investment decision.

A sunk cost refers to past expenditures. Sunk costs are not relevant since they occurred in the past and the decision of whether or not to undertake a project does not change the past.

A general (simplified) format for analyzing a capital expenditure that considers all incremental cash flows is on the following page. Note that the relevant cash flows include those found on the income statement as well as those that are not on the income statement (such as working capital). Also, some cash flows are only reflected on the income statement in part (such as the gain or loss on the sale of an asset). CASH FLOW ANALYSIS PURCHASE/REPLACEMENT DECISION

Today Intervening Years Last Year

A.

H.

In a Purchase Decision, the relevant occurrences are A, D, E, F, H, I, J, and M In a Replacement Decision, the relevant occurrences are A through M 1If the asset is sold for less than the book value, the company incurs a loss which is tax-deductible. This loss reduces taxable income and thereby creates a tax savings equal to the difference between the market value of the asset and its book value multiplied by the tax rate: Loss * t If the asset is sold for more than the book value, the company must report the difference as a profit to be taxed as ordinary income to the extent that the profit is less than the accumulated depreciation for the asset: Gain * t In the event that the asset is sold for more than the original purchase price, the gain above the original purchase price is subject to the capital gains tax rate while the accumulated depreciation is taxed as ordinary income.

< > indicates that the cash flow is an outflow. t = applicable tax rate B. The Replacement Decision

The classic capital investment decision is that of whether or not to replace a large piece of equipment.

Example

Kinky's Copying Service is considering expanding operations to include color copying service. The new service is expected to result in additional sales of $60,000 in the first year, increasing by 12% per year as word of the color copies spreads. Labor and material costs are predicted to rise by $48,000 in the first year, increasing at a 6% annual rate due primarily to inflation. To accommodate the service, a new color copier will have to be purchased at a cost of $28,000. The new machine will be depreciated using the MACRS rates for 5-year assets (20%, 32%, 19.2%, 11.52%, 11.52%, 5.76%), even though you expect that after three years of 24-hour per day operation, it will have a resale value of only $10,000 and will have to be replaced. Since the color copier can also copy black and white, one of the small existing copy machines can be sold to a local university for $4,000 rather than keeping it for the remaining three years of its useful life and scrapping it for $800. The existing copy machine was purchased for $9,000 two years ago and is also being depreciated using the same MACRS rates for 5-year assets. The expanded service would use existing floor space which would result in an allocation of depreciation totalling $5,000 per year. Also, $6,000 in administrative expenses would be allocated to the project each year; however, only $3,000 of the amount represents an actual increase in expenses not otherwise incurred by the firm. The existing floor space could be leased annually for $2,500 if the project is not accepted. An investment in working capital of $15,000 will initially be required, with additional increments of 8% per year due to both inflation and increasing sales, all of which will be recovered in the third year. Kinky's is in the 40% tax bracket. Calculate the net cash flows for each year of the project's life.

Solution

Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Incremental Revenues Increased sales 60,000 x 1.12 = 67,200 x 1.12 = 75,264 Lost lease payments (2,500) (2,500) (2,500) Total Incremental Revenues 57,500 64,700 72,764

Incremental Costs Labor & materials 48,000 x 1.06 = 50,880 x 1.06 = 53,933 Administrative expense 3,000 3,000 3,000 Total Incremental Costs 51,000 53,880 56,933 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Incremental Depreciation New Machine 28,000 28,000 28,000 MACRS rate 20.00% 32.00% 19.20% New Depreciation 5,600 8,960 5,376

Old Machine 9,000 9,000 9,000 MACRS rate 19.20% 11.52% 11.52% New Depreciation 1,728 1,037 1,037

Incremental Depreciation 3,872 7,923 4,339

Sale of Equipment Old machine - Yr. 0 Market Value 4,000 Book Value 4,320 (9,000*48%) Gain (loss) (320) Tax rate 40% Tax due (refund) (128)

Old machine - Yr. 3 Market Value 800 Book Value 518 (9,000*5.76%) Gain (loss) 282 Tax rate 40% Tax due (refund) 113

New machine - Yr. 3 Market Value 10,000 Book Value 8,064 (28,000*28.8%) Gain (loss) 1,936 Tax rate 40% Tax due (refund) 774

Working Capital Year Required Change 0 15,000 15,000 1 16,200 1,200 2 17,496 1,296 3 18,896 1,400 Putting it all together

Year 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Operating Cash Flows Revenues 57,500 64,700 72,764 Less: Costs (51,000) (53,880) (56,933) Less: Depreciation (3,872) (7,923) (4,339) Change in Taxable Income 2,628 2,897 11,492 Less: Taxes (40%) (1,051) (1,159) (4,597) Change in Net Income 1,577 1,738 6,895 Add-back depreciation 3,872 7,923 4,339 Change in Operating Cash Flow 5,449 9,661 11,234

Working Capital Requirements Additional Working Capital (15,000) (1,200) (1,296) (1,400) Working Capital Recovery 18,896

New Machine Purchase (28,000) Sale - Yr. 3 10,000 Tax on Sale (774)

Old Machine Sale - Yr. 0 4,000 Tax on Sale 128

Lost Sale - Yr. 3 (800) Tax on Sale 113 TOTAL INCREMENTAL CASH FLOW (38,872) 4,249 8,365 37,269