116

AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION

ADOPTED BY THE HOUSE OF DELEGATES

AUGUST 6-7, 2012

RESOLUTION

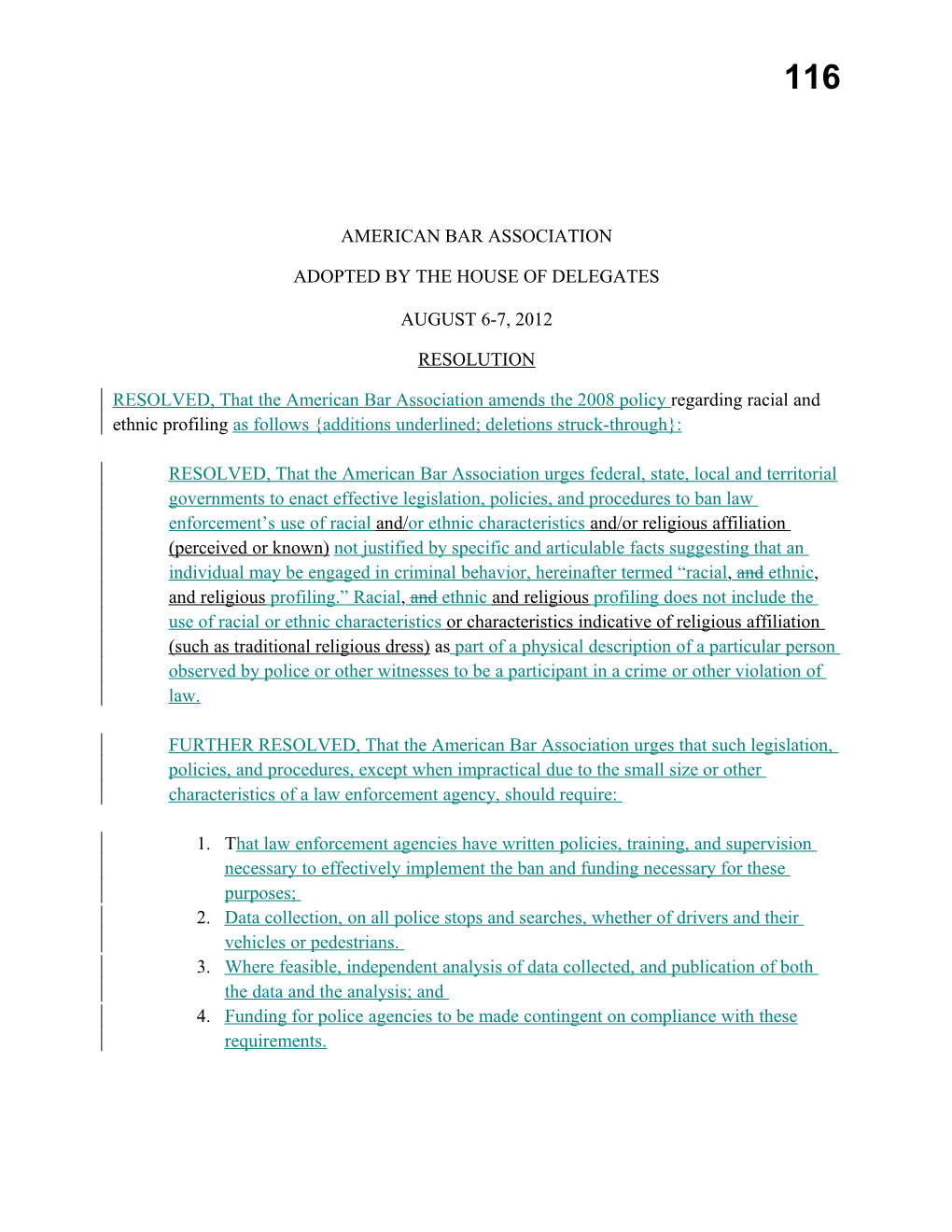

RESOLVED, That the American Bar Association amends the 2008 policy regarding racial and ethnic profiling as follows {additions underlined; deletions struck-through}:

RESOLVED, That the American Bar Association urges federal, state, local and territorial governments to enact effective legislation, policies, and procedures to ban law enforcement’s use of racial and/or ethnic characteristics and/or religious affiliation (perceived or known) not justified by specific and articulable facts suggesting that an individual may be engaged in criminal behavior, hereinafter termed “racial, and ethnic, and religious profiling.” Racial, and ethnic and religious profiling does not include the use of racial or ethnic characteristics or characteristics indicative of religious affiliation (such as traditional religious dress) as part of a physical description of a particular person observed by police or other witnesses to be a participant in a crime or other violation of law.

FURTHER RESOLVED, That the American Bar Association urges that such legislation, policies, and procedures, except when impractical due to the small size or other characteristics of a law enforcement agency, should require:

1. That law enforcement agencies have written policies, training, and supervision necessary to effectively implement the ban and funding necessary for these purposes; 2. Data collection, on all police stops and searches, whether of drivers and their vehicles or pedestrians. 3. Where feasible, independent analysis of data collected, and publication of both the data and the analysis; and 4. Funding for police agencies to be made contingent on compliance with these requirements. 116

REPORT

I. Overview

This resolution updates and strengthens ABA Policy on Police Racial and Ethnic Profiling to include religious profiling. Like profiling on the basis of race or ethnicity, profiling on the basis of religion – i.e., considering a person’s religion in deciding whether to subject that person to law enforcement scrutiny – burdens entire groups with unwanted and unjustified police attention, simply on the basis of an unfounded belief that persons who share a particular characteristic that is fundamental to their identity (in this case, their faith) are more likely to be involved in criminal activity. The practice of religious profiling, like that of racial or ethnic profiling, results in perceptions by individuals and groups that the law does not operate fairly, judging each man or woman on the basis of his or her conduct. Instead, a perception is created that justice depends on one’s religious, racial, or ethnic identity, and therefore that our institutions of justice cannot and should not be trusted.

The existing Policy recognizes that, in very specific and infrequent circumstances, racial or ethnic characteristics, along with other information, may permissibly be considered if “justified by specific or articulable facts suggesting that an individual may be engaged in criminal behavior.” The proposed resolution would include the same recognition for religion. Accordingly, just as investigating a gang that has a known racial make-up would not violate the current Policy, investigating a criminal organization that has a known religious component would not run afoul of the proposed resolution. However, just as the fact that a particular gang is comprised solely of Latinos (for example) would not justify investigating Latinos in general or at random, the fact that a self-described Christian militia cites religion as a basis for committing violent acts against government officials (for example) would not justify investigating Christians in general or at random.

The resolution effectuates a simple change. It leaves in place the current Policy’s mechanism of action (i.e., the ABA will urge federal, state, local and territorial governments to enact effective legislation, policies, and procedures to ban law enforcement’s use of profiling); it leaves in place the caveats that “profiling” does not encompass either the type of investigative activity mentioned above, or the use of the characteristic in question as part of the physical description of a specific suspect; and it leaves in place the recommendation for data collection requirements regarding “police stops and searches, whether of drivers and their vehicles or pedestrians” (a recommendation that may not have significant application in the religious profiling context). The only change wrought by the proposed resolution is to add “religious affiliation” and “characteristics indicative of religious affiliation (such as traditional religious dress)” to “race,” “ethnicity,” and “racial or ethnic characteristics” as factors that should not trigger police scrutiny, except under the narrow circumstances specified by the existing Policy.

II. Background

A. Racial and Ethnic Profiling1

1 In order to simplify the issues being presented and avoid unnecessary reframing of issues that the ABA already has considered, this section and certain other sections of this report substantially restate parallel sections in the report

1 116

Racial or ethnic profiling consists of law enforcement’s use of racial or ethnic appearance as one factor among others2 in determining whether a particular individual warrants police attention, such as a detention or search.3 While African Americans and Latinos have complained about the practice for years, the majority population and the media did not especially take notice until the late 1990s, when, for the first time, data became available that substantiated minority Americans’ claims that police had used racial or ethnic targeting to decide whom to stop, detain, and search on the highways, roads, and sidewalks of the United States.4 The data also showed that the practice was an ineffective method of identifying criminals, as studies found that police officers who engaged in profiling were less likely to find contraband in their searches of the targeted minorities than they were in their searches of whites.5

By 1999, the data had led to a rare societal consensus: more than eighty percent of all Americans of all races and ethnic groups disapproved of racial profiling by police.6 This consensus led to the enactment of statutes that took some steps against racial profiling, as well as internal regulation and/or changes in practice by some police departments. In the years since 1999, the number of states with laws against racial profiling has grown considerably, and many police departments have also mounted anti-profiling efforts. The state laws vary significantly in effect, strength, and duration, with some no longer in effect.7

accompanying the 2008 recommendation of the Criminal Justice Section to amend the ABA’s policy on racial and ethnic profiling. 2 The definition uses the phrase “one factor among others” purposely, because racial profiling is not limited to situations where law enforcement judgments are based “solely” on race. Definitions that use the term “solely” are far too narrow. For all practical purposes, they define the problem out of existence, because there are few police (or human) actions one could envision which could be said to be based “solely” on any one factor; rather, multiple causes for the actions of people are the rule.

3 As defined here, racial profiling does not include the use of racial or ethnic characteristics as part of a physical description of a particular person observed by police or other witnesses. Thus the description of a suspect which includes his or her probable race or ethnicity as reported by someone who has seen the suspect violates no principle against racial profiling.

4 For example, in Maryland, more than seventy percent of all drivers stopped by state troopers along heavily- traveled Interstate 95 were African American, even though only seventeen percent of the drivers on the highway were black. See Report of Dr. John Lamberth (plaintiff’s expert), Wilkins v. Maryland State Police, Civil No. MJG- 93-468 (D. Md. 1996).

5 See ELLIOT SPITZER, THE NEW YORK CITY POLICE DEPARTMENT’S “STOP AND FRISK” PRACTICES: A REPORT TO THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK 111, 115 (1999), tbl. IB.2; DAVID A. HARRIS, PROFILES IN INJUSTICE: WHY RACIAL PROFILING CANNOT WORK 73-90 (2002).

6 Frank Newport, Racial Profiling is Seen as Widespread, Particularly Among Young Black Men, GALLUP NEWS SERVICE (Dec. 9, 1999), http://www.gallup.com/poll/3421/racial-profiling-seen-widespread-particularly-among- young-black-men.aspx.

7 The Racial Profiling Data Collection Resource Center at Northeastern University in Boston features a current national survey of jurisdictions with anti-profiling laws. See Inst. on Race & Justice, Background and Data Collection Efforts: Jurisdictions Currently Collecting Data, RACIAL PROFILING DATA COLLECTION RES. CTR., http://www.racialprofilinganalysis.neu.edu/background/jurisdictions.php (last visited March 27, 2012).

2 116

In June 2003, the Department of Justice issued a Policy Guidance (hereinafter “Guidance”) regarding racial and ethnic profiling by federal law enforcement agencies that states: “Racial profiling in law enforcement is not merely wrong, but also ineffective. Race- based assumptions in law enforcement perpetuate negative racial stereotypes that are harmful to our rich and diverse democracy, and materially impair our efforts to maintain a fair and just society.”8 The document orders federal agencies not to use race or ethnicity, alone or in conjunction with other factors, as an indicator of suspicion in routine law enforcement activities. However, the Guidance regulates only federal agencies, which are much less likely than state or local police departments to be involved in routine law enforcement. Accordingly, federal legislation that would address profiling by state and local law enforcement officers has been introduced in each Congress since 1997 but has never passed.

B. ABA Response

In response to the developments described above, the ABA issued various resolutions and policies addressing the issue of racial and ethnic profiling. In 1999, the ABA issued a resolution urging data collection by all federal, state, local, and territorial law enforcement agencies that engage in traffic stops. Also, it urged passage of legislation requiring the Department of Justice and state attorneys general to undertake a study, based on this data, to determine whether, how, and the degree to which race-based profiling or other methods that disproportionately target or affect persons of color are used by law enforcement authorities in conducting traffic stops and searches, and to identify the most efficient and effective method of ending all such practices.

In August 2004, the ABA adopted a policy statement that recommended that the federal government and states establish criminal justice racial and ethnic task forces to design and conduct studies to determine the extent of racial and ethnic disparity in the criminal justice system. It also recommended that law enforcement agencies develop and implement policies and procedures to combat racial and ethnic profiling, including education and training, data collection and analysis, and other “best practices” that have been implemented throughout the country though voluntary programs and legislation.

In 2008, the ABA “updated and strengthened” its previous positions with a resolution that urged federal, state, local, and tribal governments to enact legislation, policies, and procedures to ban racial and ethnic profiling. The 2008 resolution reads as follows:

RESOLVED, That the American Bar Association urges federal, state, local and territorial governments to enact effective legislation, policies, and procedures to ban law enforcement’s use of racial or ethnic characteristics not justified by specific and articulable facts suggesting that an individual may be engaged in criminal behavior, hereinafter termed “racial and ethnic profiling.” Racial and ethnic profiling does not include the use of racial or ethnic characteristics as part of a physical description of a particular person observed by police or other witnesses to be a participant in a crime or other violation of law.

8 See U.S. DEP’T OF JUSTICE, GUIDANCE REGARDING THE USE OF RACE BY FEDERAL LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCIES 1 (2003), available at http://www.justice.gov/crt/about/spl/documents/guidance_on_race.pdf.

3 116

FURTHER RESOLVED, That the American Bar Association urges that such legislation, policies, and procedures, except when impractical due to the small size or other characteristics of a law enforcement agency, should require:

1. That law enforcement agencies have written policies, training, and supervision necessary to effectively implement the ban and funding necessary for these purposes; 2. Data collection, on all police stops and searches, whether of drivers and their vehicles or pedestrians. 3. Where feasible, independent analysis of data collected, and publication of both the data and the analysis; and 4. Funding for police agencies to be made contingent on compliance with these requirements.

In 2009, the ABA came out in support of the End Racial Profiling Act Of 2009. The ABA applauded the effort at legislative reform, noting that “when law-abiding citizens are treated differently by those who enforce the law simply because of their race, ethnicity, religion, or national origin, they are denied the basic respect and equal treatment that is the right of every American.”9

III. Need for Updating and Strengthening ABA Policy

A. Religious Profiling Since 9/11

The public debate and consensus described above was focused almost exclusively on racial and ethnic profiling – predominantly, the profiling of African Americans and Latinos. This focus was reflected in the resulting policies, including the Department of Justice Guidance and the ABA policies discussed above, which addressed racial and ethnic profiling only. There was little public attention paid to the issue of profiling based on religion or religious characteristics. Indeed, before 9/11, instances of religious profiling were simply less visible.10 Since 9/11, however, there have been several notable instances of religious profiling at both the federal and local level, directed at those who are, or who are perceived to be, Muslim.

In the weeks and months following 9/11, thousands of individuals hailing from Muslim countries were interviewed by the FBI.11 More than 1,000 such individuals, including both citizens and aliens, were detained, many of them for extended periods and under highly restrictive conditions, while the government investigated them to determine whether they had 9 Letter from Thomas M. Susman, Dir. of the Governmental Affairs Office at the Am. Bar Ass’n, to Representative John Conyers (Dec. 1, 2009), available at http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/migrated/poladv/letters/crimlaw/2009dec01_ERPAh_l.authcheckdam. pdf.

10 In the absence of rigorous historical data comparing religious profiling to other forms of profiling, it is difficult to know whether this is because religious profiling occurred more rarely (either in absolute numbers or relative to the size of the affected populations) or because the issue simply held less salience for the general public.

11 See David A. Harris, The War on Terror, Local Police, and Immigration Enforcement: A Curious Tale of Police Power in Post-9/11 America, 38 RUTGERS L. J. 1, 16 (2006).

4 116 any ties to 9/11 attacks;12 none were ever charged with having any such involvement.13 Reasons for detention, according to a report by the Department of Justice’s Inspector General, included “anonymous tips called in by members of the public suspicious of Arab and Muslims neighbors who kept odd schedules.”14

One might consider this response to be an understandable overreaction in the immediate aftermath of the worst terrorist attack in our nation’s history. However, the pattern of targeting Muslims for special scrutiny has persisted. In 2004, as part of “Operation Front Line” – an effort to disrupt potential terrorist plots surrounding the presidential election – immigration officials interviewed more than 2,500 immigrants. Of these, 79 percent were from majority-Muslim countries. They were asked questions such as what they thought of America, whether violence was preached at their mosques, and whether they had access to biological or chemical weapons.15

In addition, there have been several high-profile cases in recent years involving the use of FBI informants to infiltrate mosques. Evidence is mounting that such infiltration has occurred even in the absence of any specific leads or other reasons to suspect criminal activity.16 For instance, in the case of “the Newburgh Four,” the FBI’s informant testified that he was sent to several mosques to find out what the Muslim community was saying and doing rather than to uncover particular criminal or terrorist activity.17 His assignment was to “listen [and] talk to … the attendees of the mosque” and report back to his FBI handler “[i]f somebody was expressing radical views or extreme views.”18 Another FBI informant has claimed in a civil case against the FBI that he was sent to infiltrate several mosques and Islamic centers in Orange, Los Angeles, and San Bernardino counties to record essentially everything that was being said there.19

12 See generally U.S. DEP’T OF JUSTICE, OFFICE OF THE INSPECTOR GEN., THE SEPTEMBER 11 DETAINEES: A REVIEW OF THE TREATMENT OF ALIENS HELD ON IMMIGRATION CHARGES IN CONNECTION WITH THE INVESTIGATION OF THE SEPTEMBER 11 ATTACKS (2003) [hereinafter SEPTEMBER 11 DETAINEES REPORT], available at http://www.justice.gov/oig/special/0306/full.pdf.

13 See CTR. FOR DEMOCRACY AND TECH., CTR. FOR AM. PROGRESS & CTR. FOR NAT’L SEC. STUDIES, STRENGTHENING AMERICA BY DEFENDING OUR LIBERTIES: AN AGENDA FOR REFORM 8 (2003), available at http://www.cnss.org/Defending%20our%20Liberties%20report.pdf.

14 See SEPTEMBER 11 DETAINEES REPORT, supra note Error: Reference source not found, at 16.

15 Eric Lichtblau, Inquiry Targeted 2,000 Foreign Muslims in 2004, N.Y. TIMES, Oct. 31, 2008, at A17, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/31/us/31inquire.html.

16 For further information about domestic intelligence gathering practices by federal and state law enforcement agencies and the theories on which they are based, see generally FAIZA PATEL, BRENNAN CTR. FOR JUSTICE, RETHINKING RADICALIZATION 21-22 (2011).

17 Transcript of Record at 668, United States v. Cromitie, No. 09-558 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 18, 2010).

18 Id. at 669, 674, 2452.

19 Second Amended Complaint at 24-25, Monteilh v. FBI, No. 10-102 (C.D. Cal. Sept. 2, 2010). For a fuller description of the informant’s claims, see Scott Glover, Suit By Alleged Informant Says FBI Endangered His Life, L.A. TIMES, Jan. 23, 2010, at A11, available at http://articles.latimes.com/2010/jan/23/local/la-me-informant23- 2010jan23; Teresa Watanabe & Scott Glover, Man says he was informant for FBI in Orange County, L.A.TIMES, Feb. 26, 2009, at B1, available at http://articles.latimes.com/2009/feb/26/local/me-informant26; see also Thomas

5 116

The FBI also has also asked American Muslim community members to report on the religious views and activities of their fellow worshippers.20 Documents obtained through Freedom of Information Act litigation in 2009 show that the FBI’s Southern California office kept tabs on a variety of lawful First Amendment activities of American Muslims, including their religious beliefs and practices.21 Also in 2009, the Council of Islamic Organizations of Michigan, an umbrella group of nineteen mosques and community groups, filed an official complaint with Attorney General Holder because American Muslims had reported being asked to monitor people at mosques and to report on their charitable donations.22 At a 2010 presentation by the FBI’s Houston Office to Muslim community leaders, agents asked attendees to report on community members who were “taking extreme positions” and “trying to enforce a limited understanding of religion.” An example of such behavior, according to the agents, was if someone asked women in the congregation to wear a hijab (head scarf) or veil.23

The FBI is not the only federal law enforcement agency that has engaged in religious profiling. Upon return from international travel, Muslims living in the United States report being selected for secondary screening interviews in which they are interrogated about their religious views and practices. Customs and immigration enforcement officials have asked questions including, “What is your religion?” “What mosque do you attend?” “How often do you pray?” “Why did you convert to Islam?” “Do you recruit people for Islam?” and “Do you think [American Muslim religious scholar] is moderate, or an extremist?” Often, these interviews are accompanied by the confiscation and review of electronic devices, such as laptops, cell phones, and cameras.24

Religious profiling appears to be occurring at the local level, as well, with the most visible example being the recently reported activities of the New York City Police Department

Cincotta, From Movements to Mosques, Informants Endanger Democracy, PUBLIC EYE MAG. (Summer 2009), http://www.publiceye.org/magazine/v24n2/movements-to-mosques.html.

20 See, e.g., AM. CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION, EYE ON THE FBI: MOSQUE OUTREACH FOR INTELLIGENCE GATHERING (2012), available at http://www.aclu.org/files/assets/aclu_eye_on_the_fbi_-_mosque_outreach_03272012_0_0.pdf.

21 See id.; see also Memorandum from San Francisco [redacted] San Jose Residency Agency to San Francisco, Fed. Bureau of Investigation, [Redacted] Mosques/Liaison Contacts, (Aug. 25, 2005), available at http://www.aclu.org/files/fbimappingfoia/20120302/ACLURM017890.pdf; Memorandum from San Francisco [redacted] San Jose Residency Agency to San Francisco, Fed. Bureau of Investigation, Mosques/Liaison Contacts, (Dec. 9, 2004), available at http://www.aclu.org/files/fbimappingfoia/20120302/ACLURM017866.pdf.

22 Letter from the Council of Islamic Organizations of Michigan to Hon. Eric Holder, Att’y Gen. (April 15, 2009).

23 FBI Meet Houston Community Leaders, Advising to Lookout for Radicalization, THE MUSLIM OBSERVER (May 20, 2010), http://muslimmedianetwork.com/mmn/?p=6225.

24 See MUSLIM ADVOCATES, UNREASONABLE INTRUSIONS: INVESTIGATING THE POLITICS, FAITH, AND FINANCES OF AMERICANS RETURNING HOME 6 (2009), available at http://www.muslimadvocates.org/documents/Unreasonable_Intrusions_2009.pdf.

6 116

(NYPD). As described in a series of Associated Press stories beginning last summer, the NYPD has engaged in the following activities that reflect religious profiling:

A so-called “Demographics Unit” of the NYPD’s intelligence division has conducted a “mapping” program to identify neighborhoods with large Muslim populations or populations of individuals hailing from majority-Muslim countries.25

The NYPD has sent undercover agents, called “rakers,” to compile reports about the patrons of cafes, clubs, barber shops, and other business establishments frequented by Muslims in the communities identified through its mapping program.26

The NYPD has employed so-called “mosque crawlers” to infiltrate mosques and monitor sermons without any indication of wrongdoing.27 It also produced an analytical report on every mosque within 100 miles of New York City.28

NYPD officers infiltrated Muslim student associations at college campuses, not only in New York City but throughout the Northeast. In one case, an agent attended a Muslim student association’s whitewater rafting trip and reported back on the number of times students were praying.29

A 2006 NYPD intelligence report recommended increasing surveillance of the City’s Shiite Muslim population, on the ground that doing so might assist in identifying Iranian terrorists.30

The above instances of religious profiling are consistent with the explicit connection some law enforcement agencies have drawn between religiosity and terrorism. For instance, an article published in the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin by FBI counterterrorism analysts, which purports to describe the process of “radicalization” to terrorism, includes “liv[ing] every detail of

25 See Adam Goldman & Matt Apuzzo, Inside the Spy Unit that NYPD Says Doesn’t Exist, ASSOCIATED PRESS (Aug. 31, 2011), http://ap.org/Content/AP-In-The-News/2011/Inside-the-spy-unit-that-NYPD-says-doesnt-exist; Matt Apuzzo, Eileen Sullivan & Adam Goldman, NYPD Eyed U.S. Citizens in Intel Efforts, ASSOCIATED PRESS (Sept. 22, 2011), http://ap.org/Content/AP-In-The-News/2011/NYPD-eyed-US-citizens-in-intel-effort.

26 See Goldman & Apuzzo, supra note Error: Reference source not found.

27 See Adam Goldman & Matt Apuzzo, With CIA Help, NYPD Moves Covertly in Muslim Areas, ASSOCIATED PRESS (Aug. 24, 2011), http://www.ap.org/Content/AP-in-the-News/2011/With-CIA-help-NYPD-moves-covertly-in- Muslim-areas.

28 Id.

29 See Chris Hawley, NYPD Monitored Muslim Students All Over Northeast, ASSOCIATED PRESS (Feb. 18, 2012), http://ap.org/Content/AP-In-The-News/2012/NYPD-monitored-Muslim-students-all-over-Northeast.

30 See Adam Goldman, Chris Hawley, Eileen Sullivan & Matt Apuzzo, Document Shows NYPD Eyed Shiites Based on Religion, ASSOCIATED PRESS (Feb. 3, 2012), http://www.ap.org/Content/AP-In-The-News/2012/Document- shows-NYPD-eyed-Shiites-based-on-religion.

7 116 the religion” as a sign that an individual may be in the second of four phases of becoming a terrorist.31 A 2007 report by the NYPD is even more explicit, citing the wearing of traditional Islamic clothing, growing a beard, and giving up cigarettes and drinking (as required by the Muslim religion) as behaviors for which officers should be on the lookout as potential indicators of a terrorist trajectory.32

Similarly, law enforcement training materials have emerged that portray Islam and/or Muslims as inherently or largely violent. In the summer of 2011, a reporter acquired materials from FBI training presentations that included statements that “main stream” American Muslims are likely to be terrorist sympathizers, that the Prophet Mohammed was a “cult leader,” and that the Islamic practice of giving charity is no more than a “funding mechanism for combat.” The materials also included a chart indicating a high correlation between devout adherence to Islam and violence. Materials from an FBI instructional presentation included statements that “[a]ny war against non-believers is justified” under Muslim law and that a “moderating process cannot happen if the Koran continues to be regarded as the unalterable word of Allah.” The stated purpose of a briefing on the subject of allegedly religious-sanctioned lying was to “identify the elements of verbal deception in Islam and their impacts on Law Enforcement.”33

The Department of Justice acknowledged the inappropriateness of these statements and has reportedly removed 876 offensive or inaccurate pages used in 392 training presentations as a result of an agency-wide review,34 but it is not always clear when or how training materials become part of law enforcement agencies’ curriculum. In January 2011, when it emerged that the NYPD had shown an anti-Muslim film, The Third Jihad, in a training session, the NYPD claimed that the film had been shown once or twice by mistake. A year later, documents obtained through New York’s Freedom of Information Law showed that the film had been shown over the course of at least three months to at least 1,500 officers.35 The NYPD’s internal investigation concluded that the film had been provided by an agent of the Department of Homeland Security, but DHS denies authorizing its use.36

31 Carol Dyer et al., Countering Violent Extremism, FED. BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION L. ENFORCEMENT BULL. (FED. BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION, WASHINGTON, D.C.), Dec. 2007, at 5, available at http://www.fbi.gov/stats- services/publications/law-enforcement-bulletin/2007-pdfs/dec07leb.pdf.

32 MITCHELL D. SILBER & ARVIN BHATT, NYPD INTELLIGENCE DIVISION, RADICALIZATION IN THE WEST: THE HOMEGROWN THREAT 38-39, 61 (2009), available at http://www.nyc.gov/html/nypd/downloads/pdf/public_information/NYPD_Report-Radicalization_in_the_West.pdf.

33 See Spencer Ackerman, FBI Teaches Agents: “Mainstream” Muslims Are “Violent, Radical,” WIRED.COM (Sept. 14, 2011), http://www.wired.com/dangerroom/2011/09/fbi-muslims-radical/all/1.

34 See Letter from Richard J. Durbin, U.S. Senator, to Robert Mueller, Dir. of the Fed. Bureau of Investigation (March 27, 2012), available at http://www.wired.com/images_blogs/dangerroom/2012/03/FBI-training-letter.pdf.

35 See Michael Powell, In Police Training, a Dark Film on U.S. Muslims, N.Y. TIMES Jan. 23, 2012, at A1, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/24/nyregion/in-police-training-a-dark-film-on-us-muslims.html? pagewanted=all.

36 See Omar Tewfik, DHS Claims No Connection to “The Third Jihad,” ARAB AM. INST. (Mar. 7, 2012), http://www.aaiusa.org/blog/entry/dhs-claims-no-connection-to-the-third-jihad/.

8 116

In short, since 9/11, a variety of actions taken by federal and local law enforcement agencies have been expressly or implicitly premised on the notion that a person’s Muslim faith, particularly when deeply held, is itself a potential indicator of terrorism and a basis for law enforcement scrutiny. Such activities constitute religious profiling, and the evidence suggests that they have become disturbingly commonplace at both the federal and local level.

B. Harms of Religious Profiling

Religious profiling and racial or ethnic profiling share the same basic feature: the pernicious belief that a characteristic which is fundamental to a person’s identity, and which accordingly receives heightened protection under the Constitution, is in fact a basis for law enforcement scrutiny. Not surprisingly, then, the harms caused by the different types of profiling are the same. The report accompanying the 2008 resolution to update and strengthen the ABA’s racial and ethnic profiling policies identified several of these harms; each applies with equal force to religious profiling.

For instance, the 2008 report states: “Law enforcement action based, even in part, on racial or ethnic characteristics is less effective than law enforcement that focuses on the actual law-breaking or dangerous behavior with which law enforcement is and should be concerned.” The religious profiling discussed above has been remarkably ineffective. As mentioned, the post-9/11 roundup and detention of more than a thousand individuals hailing from Muslim countries, which was billed as necessary to investigate the 9/11 attacks, did not yield a single criminal charge relating to those attacks. The FBI’s post-9/11 interviews of thousands of Muslims were similarly unproductive: two years later, the government still had not bothered to analyze the information collected,37 and agents confirmed that the interviews “produced exactly no useful information.”38 The 2004 Operation Front Line effort to disrupt potential plots surrounding the presidential election by interviewing thousands of immigrants, 79 percent of whom were from majority-Muslim countries, yielded no terrorism or national security charges.39 The NYPD’s “mosque crawler” program reportedly was based on a program previously initiated by the CIA overseas – a program that former senior CIA officials have described as ineffective.40

This ineffectiveness should come as no surprise. In the wake of 9/11, a group of senior U.S. intelligence specialists warned against using such profiling as a means of combating terrorism. In the words of one of these specialists: “[F]undamentally, believing that you can achieve safety by looking at characteristics instead of behaviors is silly.”41 Even when focusing 37 David A. Harris, Law Enforcement and Intelligence Gathering in Muslim and Immigrant Communities After 9/11, 34 N.Y.U. REV. L. & SOC. CHANGE 123, 135 n.43 (2010).

38 Tom Lininger, Sects, Lies, and Videotape: The Surveillance and Infiltration of Religious Groups, 89 IOWA L. REV. 1201, 1253 n.247 (2004).

39 See Lichtblau, supra note Error: Reference source not found.

40 See Matt Apuzzo, Adam Goldman & Eileen Sullivan, NYPD Spying Program Yielded Only Mixed Results, ASSOCIATED PRESS (Dec. 23, 2011), http://ap.org/Content/AP-In-The-News/2011/NYPD-spying-programs-yielded- only-mixed-results.

41 Bill Dedman, Memo Warns Against Use of Profiling as Defense, BOSTON GLOBE, Oct. 12, 2001, at A27.

9 116 specifically on terrorism inspired by religious ideology, the idea that one can find the terrorist by honing in on the religion is empirically flawed. The percentage of terrorists within any given religion is far too miniscule to justify using resources in such a manner. Moreover, research suggests that terrorists who claim to be inspired by religion are not particularly likely to be found at houses of worship or exhibiting signs of devout religiosity. A study by the British intelligence agency “MI5” found that, “[f]ar from being religious zealots, a large number of those involved in terrorism do not practise their faith regularly. Many lack religious literacy and could actually be regarded as religious novices.”42 A highly respected social scientist’s review of 500 cases, backed by multiple other empirical studies, found that “a lack of religious literacy and education appears to be a common feature among those that are drawn to [terrorist] groups.”43 Indeed, there is evidence that “a well-established religious identity actually protects” against violent radicalization.44

The 2008 ABA report also notes that the practice of racial and ethnic profiling “leads to great resentment and feelings of antipathy toward police by the majority of persons in these racial and ethnic groups, who behave lawfully, and has, therefore, become a major point of friction between police and those they serve.” Perceptions of religious profiling since 9/11 unquestionably have generated significant apprehension and resentment on the part of the Muslim American community. The leader of one national Muslim organization testified before Congress that law enforcement’s attitudes and practices have created “fear and suspicion within the Muslim community toward law enforcement.”45 A representative of another major American Muslim group testified that “[t]he perception of the community has become one where they believe they are viewed as suspect rather than partner in the War on Terror, and that their civil liberties are ‘justifiably’ sacrificed upon the decisions of federal agents.”46 The President of the Islamic Society of North America notes that the types of practices discussed above “have sown a corrosive fear . . . that FBI informers are everywhere, listening,” and that law enforcement agents view Muslim Americans “as objects of suspicion.”47

42 Alan Travis, MI5 Report Challenges Views on Terrorism in Britain, GUARDIAN (Aug. 20, 2008), http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2008/aug/20/uksecurity.terrorism1.

43 TUFYAL CHOUDHURY, DEPT. FOR COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOV’T, THE ROLE OF MUSLIM IDENTITY POLITICS IN RADICALIZATION (A STUDY IN PROGRESS) 6 (2007) (emphasis added), available at http://www.communities.gov.uk/documents/communities/pdf/452628.pdf; MARC SAGEMAN, LEADERLESS JIHAD: TERROR NETWORKS IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY 31, 51-52 (2008).

44 Travis, supra note Error: Reference source not found.

45 See Racial Profiling and the Use of Suspect Classifications in Law Enforcement Policy: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 111th Cong. 62 (2010) (written testimony of Farhana Khera, President and Exec. Dir., Muslim Advocates) [hereinafter “Khera June 2010 Testimony”].

46 Radicalization, Information Sharing and Community Outreach: Protecting the Homeland from Homegrown Terror: Hearing before the Subcomm. on Intelligence, Info. Sharing and Terrorism Risk Assessment of the H. Comm. on Homeland Sec., 110th Cong. 6 (2007) (statement of Sireen Sawaf, Gov’t Relations Dir., S. Cal. Muslim Pub. Affairs Council), available at http://hsc-democrats.house.gov/SiteDocuments/20070405120720-29895.pdf.

10 116

A 2008 Vera Institute report on the effect of post-9/11 policing on sixteen Arab- American communities across the United States confirms the existence of these sentiments. The report found that some Arab American communities “were more afraid of law enforcement agencies – especially federal law enforcement agencies – than they were of acts of hate or violence, despite an increase in hate crimes.”48 Law enforcement officials themselves acknowledge this dynamic, with FBI officials noting that American Muslim communities “al- most unanimously feel that government agents treat them as suspects and view all Muslims as extremists.”49 In the wake of news reports about the NYPD’s surveillance of the Muslim community, prominent Muslim New Yorkers boycotted the Mayor’s interfaith breakfast and refused to meet with Police Commissioner Kelly, and community groups staged protests.50

The ABA’s 2008 report on racial and ethnic profiling also states, “If police agencies can show the public and the media that the police are operating impartially and objectively and only when race is a critical fact in an investigation, there will be more citizen cooperation with police agencies.” Nowhere is the need for citizen cooperation with law enforcement greater than in the context of domestic counterterrorism efforts, and nowhere does profiling – in this case, religious profiling – more directly jeopardize that cooperation.

Law enforcement officials have repeatedly emphasized that the cooperation of the American Muslim community has been instrumental in learning about and thwarting terrorist plots. As stated by the nation’s top law enforcement official, Attorney General Eric Holder: “[T]he cooperation of Muslim and Arab-American communities has been absolutely essential in identifying, and preventing, terrorist threats.”51 In part, this is because tips about potential terrorist plots are most likely to come from “people who live in the communities where sleeper cells reside and can tell authorities who’s new in the neighborhood and who seems to have income without holding a job.”52 According to multiple studies, Muslims have provided key

47 Paul Vitello and Kirk Semple, Muslims Say F.B.I. Tactics Sow Anger and Fear, N.Y. TIMES, Dec. 17, 2009, at A1, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/18/us/18muslims.html.

48 NICOLE J. HENDERSON ET AL., U.S. DEP’T OF JUSTICE, POLICING IN ARAB-AMERICAN COMMUNITIES AFTER SEPTEMBER 11 ii (2008), available at http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/221706.pdf. For the full study, see NICOLE J. HENDERSON ET AL., VERA INST. OF JUSTICE, LAW ENFORCEMENT AND ARAB-AMERICAN COMMUNITY RELATIONS AFTER SEPTEMBER 11, 2001: ENGAGEMENT IN A TIME OF UNCERTAINTY (2006), available at http://www.vera.org/content/law- enforcement-and-arab-american-community-relations-after-september-11-2001-engagement-tim.

49 Dyer et al., supra note Error: Reference source not found, at 8.

50 See Some Muslim Leaders Boycott Bloomberg’s Interfaith Breakfast, CBS NEW YORK (Dec. 30, 2011), http://newyork.cbslocal.com/2011/12/30/muslims-boycotting-bloombergs-interfaith-breakfast/; Colleen Long, Kelly Meets With Muslim Leaders to Talk Surveillance, ASSOCIATED PRESS (Mar. 6, 2012), http://abclocal.go.com/wabc/story?section=news/local/new_york&id=8570155; Stephen Nessen, Muslim Groups Protest NYPD Practices, WNYC NEWS (Feb. 3, 2012), http://www.wnyc.org/blogs/wnyc-news- blog/2012/feb/03/muslim-groups-protest-nypd-practices/.

51 Eric Holder, U.S. Att’y Gen., Speech at Muslim Advocates’ Annual Dinner (Dec. 10, 2010), available at http://www.justice.gov/iso/opa/ag/speeches/2010/ag-speech-1012101.html.

52 Kim Zetter, Why Racial Profiling Doesn’t Work, SALON (Aug. 22, 2005), http://dir.salon.com/story/news/feature/2005/08/22/racial_profiling/index.html.

11 116 information in 40 percent of the terrorist plots that have been foiled to date.53 To name just one example, in the prosecution of the so-called “Lackawanna Six,” it was Lackawanna’s Yemeni community that brought the defendants to the FBI’s attention.54

The resentment and fear generated by tactics that reflect religious profiling (as described above) threaten this cooperative relationship. A recent empirical study of American Muslims in the New York area found “a robust correlation between perceptions of procedural justice and both perceived legitimacy and willingness to cooperate among Muslim American communities in the context of antiterrorism policing.”55 In other words, American Muslim communities were more likely to cooperate with counterterrorism efforts if they perceived these efforts to be carried out in a legitimate manner. In light of the perceived illegitimacy of some current tactics, Muslim community leaders report that individuals are “more reluctant to call the authorities when needed.”56 Prominent Muslim organizations have urged community members not to speak with law enforcement attorneys without the presence or advice of an attorney,57 and a national coalition of American Muslim organizations has warned that it will cease cooperating with the FBI if the practice of mosque infiltration continues.58

Many law enforcement agents acknowledge that religious profiling endangers counterterrorism efforts by hindering cooperation. Responding to the NYPD’s widespread, non- threat-based surveillance of the Muslim community both in and outside of New York City, the top FBI official in New Jersey stated, “We’re starting to see cooperation pulled back. People are concerned that they’re being followed, they’re concerned that they can’t trust law enforcement, and it’s having a negative impact.” He warned: “When people pull back cooperation, it creates additional risks, it creates blind spots. It hinders our ability to have our finger on the pulse of

53 See, e.g., CHARLES KURZMAN, TRIANGLE CTR. ON TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SEC., MUSLIM-AMERICAN TERRORISM SINCE 9/11: AN ACCOUNTING 5 (2011), available at http://sanford.duke.edu/centers/tcths/about/documents/Kurzman_Muslim- American_Terrorism_Since_911_An_Accounting.pdf; KEVIN STROM ET AL., INST. FOR HOMELAND SEC. SOLUTIONS, BUILDING ON CLUES: EXAMINING SUCCESSES AND FAILURES IN DETECTING U.S. TERRORIST PLOTS, 1999-2009 19 (2010), available at https://www.ihssnc.org/portals/0/Building_on_Clues_Strom.pdf.

54 See Harris, supra note Error: Reference source not found, at 127-28.

55 Tom R. Tyler, Stephen Schulhofer & Aziz Z. Huq, Legitimacy and Deterrence Effects in Counterterrorism Policing: A Study of Muslim Americans, 44 L. & SOC’Y REV. 365, 373-379 (2010).

56 Khera June 2010 Testimony, supra note Error: Reference source not found.

57 See, e.g., MUSLIM ADVOCATES, URGENT COMMUNITY ALERT: SEEK LEGAL ADVICE BEFORE TALKING TO THE FBI, available at http://www.muslimadvocates.org/FBI_IVU_COMMUNITY%20ALERT.pdf; see also Reports of FBI Visits Prompt Reminder of Legal Rights, COUNCIL ON AMERICAN-ISLAMIC RELATIONS (May 21, 2010), http://www.cair.com/ArticleDetails.aspx?ArticleID=26404&&name=n&currPage=1; COUNCIL ON AMERICAN- ISLAMIC RELATIONS, AMERICAN MUSLIM CIVIC POCKET GUIDE, http://www.cair.com/CivilRights/KnowYourRights.aspx#9.

58 Press Release, Council on American-Islamic Relations & Ctr. for Constitutional Rights, ‘Newburgh Four’ Raises Concern of FBI Tactics in Terror Cases (Oct. 21, 2010), available at http://www.cair-ny.org/content/? content_id=407.

12 116 what’s going on around the state, and thus it causes problems and makes the job of [law enforcement] much, much harder.”59

Finally, the 2008 ABA report on racial and ethnic profiling quotes the Department of Justice Guidance, which states, “Race-based assumptions in law enforcement perpetuate negative racial stereotypes that are harmful to our rich and diverse democracy, and materially impair our efforts to maintain a fair and just society.” Religious profiling by law enforcement after 9/11 feeds into stereotypes about Muslims held by the general public. These stereotypes are reflected in the increasing opposition to the building of mosques and Islamic community centers in communities across the country. The public outcry following the Park 51 proposal (involving the establishment of an Islamic center two blocks from the former location of the World Trade Center towers) is only the most visible example. Towns across the country have changed their local zoning ordinances to block the building of mosques.60 It is easy to see why the public is nervous about mosques when law enforcement agents are targeting them for infiltration even in the absence of any specific leads. The message is clear, and the public receives it: Mosques are a good place to find terrorists.

Similarly, the suggestion by some law enforcement agencies that pious adherence to the Muslim faith correlates with violence and/or radicalization fuels the growing public fear of Sharia, or Islamic law. State and local legislatures have introduced (and, in some cases, enacted) legislation that ranges from outlawing judicial consideration of any foreign law to designating people who observe Sharia as terrorists and criminalizing any support for such groups.61 The ABA has responded to this movement with a policy statement opposing federal or state laws that impose blanket prohibitions on courts’ consideration of foreign or international law, or that prohibit consideration of the entire body of law or doctrine of a particular religion. Nonetheless, when the FBI cites “liv[ing] every detail of the religion” as a possible sign of terrorism,62 it is not difficult to understand why so many Americans perceive adherence to Sharia as a threat.

In sum, the harms caused by religious profiling are identical to those caused by racial and ethnic profiling. The practice is ineffective and thus wastes scarce law enforcement resources. It alienates the communities being profiled and discourages their cooperation with law enforcement efforts – to the detriment of public safety. And it perpetuates negative stereotypes, undermining tolerance and respect for diversity, to the detriment of society at large.

59 Samantha Henry, NJ FBI: NYPD Monitoring Damaged Public Trust, ASSOCIATED PRESS (Mar. 7, 2012), http://ap.org/Content/AP-In-The-News/2012/NJ-FBI-NYPD-monitoring-damaged-public-trust.

60 See, e.g., Editorial, No Room for Tolerance, N.Y. TIMES Sept. 19, 2011, at A26, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/19/opinion/no-room-for-tolerance.html.

61 See Bob Smietana, Tennessee Bill Would Jail Some Shariah Followers, TENNESSEAN (Feb. 23, 2011), available at http://www.lexisnexis.com/; Omar Sacirbey, Anti-Shariah Movement Loses Steam in State Legislatures, HUFFINGTON POST (Mar. 25, 2012), http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/03/25/anti-shariah-movement-loses- steam_n_1374083.html.

62 Dyer et al., supra note Error: Reference source not found, at 5.

13 116

In addition, religious profiling generates one harm that is specific to its targets: it discourages the open and uninhibited practice of religion. When the NYPD cites the wearing of traditional religious clothing as a potential sign of radicalization and urges police officers to be on the watch, the likely effect is to deter some individuals from wearing traditional religious clothing, even if that is how they wish to (or believe they should) manifest their faith. Similarly, when communities learn that informants for the FBI or the local police are infiltrating their mosques, recording what individual congregants say about their own religious views, and reporting those views as “intelligence,” such information can only serve to dissuade community members from mosque attendance. Indeed, in a lawsuit brought by members of the Muslim community in Irvine, California, plaintiffs alleged that they attended services less frequently, and were less willing to welcome newcomers in accordance with the edicts of their religion, after learning that an FBI informant had surveilled their mosque.63 Religious profiling thus not only offends constitutional principles of Equal Protection (as does racial and ethnic profiling) by discriminating against individuals on the basis of a constitutionally protected characteristic; it also chills the free exercise of religion under the First Amendment.

C. Need for ABA Action

As discussed above, most previous efforts to address the problem of profiling—including the efforts of the Department of Justice, those of many state and local governments, and those of the ABA – were a direct outcome of a national discussion about racial and ethnic profiling that began more than a decade before 9/11 and, accordingly, have focused on race and ethnicity. Yet singling people out for law enforcement scrutiny on the basis of their faith is just as odious and contrary to our nation’s pluralistic values as singling them out on the basis of their race or ethnicity, and the harms that flow from the practice are the same.

In recent years, advocates and lawmakers have undertaken various efforts to rectify the problem, but thus far without success. For instance, a large group of national and community organizations has repeatedly petitioned the Department of Justice to revise its 2003 Guidance to extend its profiling ban to religion, as well as national origin,64 and to eliminate various other loopholes in the Department’s policy. The group’s efforts have been to no avail, despite the fact that the organizations have been joined in their campaign by Senator Richard Durbin and Representative John Conyers.65 Advocates were successful in persuading lawmakers to include

63 See Class Action Complaint at ¶¶ 192, 212, Fazaga et al. v. FBI, No. 11-cv-00301 (C.D. Cal. Feb. 22, 2011).

64 The proposed policy statement does not include profiling on the basis of national origin. Recent examples of such profiling in the counterterrorism context appear to be proxies for religious profiling, as the targeted countries of origin are almost invariably countries with majority-Muslim populations. Under the proposed policy statement, such instances – such as the NYPD’s request for lists of Pakistani taxi drivers – should be treated as religious profiling, as religion is clearly a consideration in selecting the national origin of interest.

65 See Tong, Take Action: Tell DOJ to Reform their 2003 Guidance on Racial Profiling, RIGHTS WORKING GROUP (Mar. 26, 2012 5:04 PM), http://www.rightsworkinggroup.org/content/take-action-tell-doj-reform-their-2003- guidance-racial-profiling.

14 116 religion in the most recent versions of the End Racial Profiling Act;66 however, as noted above, this legislation has stalled in every Congress since 1997.

Nonetheless, a window of opportunity may now exist. The failure of police in Sanford, Florida, to arrest the man who killed Trayvon Martin in the weeks after the shooting has led many to question whether current law sufficiently prevents the consideration of race in law enforcement decisions, reinvigorating the push to enact the End Racial Profiling Act,67 for which the ABA has already voiced its support. Furthermore, the revelations about the NYPD’s surveillance of Muslim communities has sparked a national conversation about the role that religion may permissibly play in law enforcement officers’ decisions about where and how to focus their attention and resources. The ABA has been active in the past in supporting policies and legislation that would effectively ban religious and ethnic profiling. It could play a critical role in the current debate – and honor its historical commitment to this issue – by updating its policy to include profiling on the basis of religion, thereby adding a strong, authoritative voice to the argument against this invidious practice.

III. Conclusion

The ABA has stood firm against the practice of racial and ethnic profiling, recognizing that it is ineffective, unjust to the individual, and poisonous to our values as a pluralistic nation. The practice of targeting individuals on the basis of their religion is equally invidious, and the ABA should stand equally firm against it. In view of the mounting evidence that federal and local law enforcement agencies are engaging in religious profiling, the ABA should amend its policy on racial and ethnic profiling to make clear that a person’s faith should not invite law enforcement scrutiny.

Respectfully Submitted,

Kay H. Hodge, Chair Janet I. Levine, Chair Section of Individual Rights & Responsibilities Criminal Justice Section

August 2012

66 See S. 1670, 112th Cong. (2011), available at http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/z?c112:S.1670:; H.R. 3618, 112th Cong. (2011), available at http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/z?c112:H.R.3618:.

67 Mark K. Matthews, Senate Panel Eyes Racial Profiling Amid Trayvon Case, ORLANDO SENTINEL, Apr. 18, 2012, at A13.

15 116

GENERAL INFORMATION FORM

Submitting Entity: Section of Individual Rights & Responsibilities Criminal Justice Section

Submitted By: Kay H. Hodge, Chair Section of Individual Rights & Responsibilities

Janet I. Levine, Chair Criminal Justice Section

1. Summary of Resolution(s).

This resolution urges federal, state, local and territorial governments to enact effective legislation, policies, and procedures to ban law enforcement’s use of racial and/or ethnic characteristics and/or religious affiliation (perceived or known) not justified by specific and articulable facts suggesting that an individual may be engaged in criminal behavior, hereinafter termed “racial, ethnic, and religious profiling.” Racial, ethnic, and religious profiling does not include the use of racial or ethnic characteristics or characteristics indicative of religious affiliation (such as traditional religious dress) as part of a physical description of a particular person observed by police or other witnesses to be a participant in a crime or other violation of law.

2. Approval by Submitting Entity.

The Council of the Section of Individual Rights and Responsibilities approved the filing of this Resolution with Report on February 3, 2012, during its Midyear Meeting in New Orleans, Louisiana.

The Council of the Criminal Justice Section approved co-sponsorship of this Resolution with Report on April 14, 2012, during its Spring Meeting in Los Angeles, California.

3. Has this or a similar resolution been submitted to the ABA House of Delegates or Board of Governors previously?

Yes.

4. What existing Association policies are relevant to this resolution and how would they be affected by its adoption?

Several previous ABA resolutions and policies have addressed profiling and related issues:

In 1999, the ABA adopted a resolution on the collection of data about race and ethnicity by all federal, state, local and territorial law enforcement agencies that engage in traffic stops. It also urged passage of legislation requiring DOJ and state attorney's general to undertake a study, based on this data, to determine whether, how and the degree to which race-based profiling or other methods that disproportionately target or affect persons of color are used by law enforcement authorities in conducting traffic stops and searches and, if so, to identity the most efficient and effective method of ending all such practices.

16 116

In August, 2004, the ABA adopted policy that recommended that the federal government and states establish criminal justice racial and ethnic task forces to design and conduct studies to determine the extent of racial and ethnic disparity in the criminal justice system.

In 2008, the ABA adopted a resolution urging federal, state, local and territorial governments to enact effective legislation, policies, and procedures to ban racial or ethnic profiling by law enforcement agencies and police officers engaging in domestic law enforcement.

This proposed resolution would build upon these previous policies by including religion, along with race and ethnicity, as improper bases for law enforcement decisions.

5. What urgency exists which requires action at this meeting of the House?

In recent years, evidence has accumulated that law enforcement agencies are engaging in religious profiling in a variety of contexts. For example, law enforcement agents at both the federal and local level are reportedly targeting mosques for investigation even when they lack any basis for suspecting criminal activity. Guidelines used by law enforcement agencies (both federal and local) have cited ordinary religious attributes and behaviors-- such as growing a beard or wearing traditional religious clothing--as potential signs of terrorism. And training materials for law enforcement agents have come to light that directly link a particular religious affiliation with a propensity toward violence. The impact on certain religious communities in the U.S. is direct and immediate, both in terms of chilling their exercise of religion and dissuading them from cooperating with law enforcement. Prompt action is accordingly needed.

6. Status of Legislation. (If applicable.)

The sponsoring entities are not aware of any relevant legislation pending at this time.

7. Brief explanation regarding plans for implementation of the policy, if adopted by the House of Delegates.

If adopted, the policy would be used to encourage law enforcement agencies to revise guidelines and training materials regarding the use of religion as a basis for profiling.

8. Cost to the Association. (Both direct and indirect costs.)

The resolution’s adoption would not result in direct cost to the Association.

9. Disclosure of Interest. (If applicable.)

There are no known conflicts of interest.

17 116

10. Referrals.

All ABA Sections and Divisions

ABA Standing Committee on Law and National Security

ABA Standing Committee on Public Education

11. Contact Person. (prior to the meeting)

Estelle H. Rogers, Delegate ABA Section of Individual Rights and Responsibilities 3252 S Street, NW Washington, DC 20007 Tel.: 202/337-3332 E-mail: [email protected]

Elizabeth Goitein, Vice Chair, National Security and Civil Liberties Committee ABA Section of Individual Rights and Responsibilities Brennan Center for Justice 1730 M Street, NW Suite 43 Washington, DC 20036 Tel: 202/249-7192 Cell: 202/302-7331 E-mail: [email protected]

Devon Chaffee, Chair, National Security and Civil Liberties Committee ABA Section of Individual Rights and Responsibilities ACLU 915 15th St., NW Washington, DC 20005 Tel.: 202/675-2331 Cell: 202/906-9620 E-mail: [email protected]

Tanya N. Terrell, Director ABA Section of Individual Rights and Responsibilities 740 15th St., NW Washington, DC 20005 Tel: 202/662-1030 Cell: 202/641-2149 E-mail: [email protected]

18 116

12. Contact Person. (who will present the report to the House)

Richard M. Macias Richard Macias & Associates 2741 Prewett Street P. O. Box 31569 Los Angeles, CA 90031-0569 Tel.: 323/224-3939 Fax: 323/225-4485 E-mail: [email protected]

Estelle H. Rogers 3252 S Street, NW Washington, DC 20007 Tel.: 202/337-3332 E-mail: [email protected]

19 116

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

a) Summary of the resolution:

This resolution urges federal, state, local and territorial governments to enact effective legislation, policies, and procedures to ban law enforcement’s use of racial and/or ethnic characteristics and/or religious affiliation (perceived or known) not justified by specific and articulable facts suggesting that an individual may be engaged in criminal behavior, hereinafter termed “racial, ethnic, and religious profiling.” Racial, ethnic, and religious profiling does not include the use of racial or ethnic characteristics or characteristics indicative of religious affiliation (such as traditional religious dress) as part of a physical description of a particular person observed by police or other witnesses to be a participant in a crime or other violation of law. b) Summary of the issue which the resolution addresses:

Current ABA policy addresses racial and ethnic profiling, but not religious profiling. Since 9/11, religious profiling has become an increasingly common practice, with law enforcement agents reportedly targeting mosques for investigation even absent any indication of wrongdoing; law enforcement guidelines suggesting that ordinary religious attributes and behaviors may be signs of incipient terrorism; and law enforcement training materials equating Islam with violence. c) Explanation of how the proposed policy position will address the issue:

The proposed policy position will make clear the ABA considers religion, like race or ethnicity, to be an improper basis on which to make law enforcement decisions, and it will encourage federal, state, local and territorial governments to take the necessary actions to ban religious profiling. The resolution would not alter or expand the data collection requirement contained in the 2008 policy. d) Summary of any minority views or opposition which have been identified:

There is no known opposition to this proposal.

20