The Evolution of a Vision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education (EDUC) This Course Covers Quantitative Methods in Marketing Analytics

ECON 462 SEMINAR IN QUANTITATIVE MARKETING: TIME SERIES ECONOMETRICS (4) Education (EDUC) This course covers quantitative methods in marketing analytics. The course will concentrate on theory and application of time series econometrics to marketing EDUC 150 PROSPECTIVE TEACHERS (3) topics such as pricing, promotion, branding and marketing return on investment. Focuses on realities of the classroom from the teacher’s point of view. Includes child The course will make extensive use of advanced time series econometrics methods development, teachers’ roles and responsibilities, and the culture of schools in a beginning with the multiple regression model. Prerequisite: ECON 304, 305, and 317. changing society. Includes an apprenticeship with a teacher. Grade only. Prerequisite: ECON 481 SEMINAR IN ECOLOGICAL ECONOMICS (4) consent of instructor. An exploration of the sustainable use of three types of capital: natural, human, and EDUC 250 TEACHING IN A CHANGING WORLD (3) financial. Public and private sector solutions are developed to promote the long- This course is designed to provide an introduction to the classroom from teachers’ term viability of market-based economies. Topics include pollution control, fishery points of view. Areas of content include child and adolescent development, teachers’ management welfare measurement, performance metrics, and product design. roles and responsibilities, the culture of schools in a changing society, as well as Prerequisites: ECON 204, 205, 304, 305 and 317, or consent of instructor. an apprenticeship with a practicing teacher. Particular emphasis will be on teacher ECON 488 SEMINAR IN ECONOMICS AND Law OF BUSINESS REGULATION (4) decision-making. Institutional changes that could improve teacher and student Advanced topics in economic and legal aspects of business regulation. -

Shooting in Madison; Arrest in Jefferson

HONORING SHERIFF HOBBS Sheriff Hobbs' Boots and Barrels fundraisers See pages 10 - 11 See pages 10 - 11 MONTICELLO NEWS 151 Years of Serving the Monticello Community www.ecbpublishing.com Wednesday, April 17, 2019 No. 7 75¢+Tax ShootingAshley Hunter JCSO inreceived aMadison; transferred arrestshot at his vehicle in while Jefferson the While Cpl. Ryland spoke ECB Publishing, Inc. 911 call from the Madison two parties were traveling with the victim, a County Sheriff's Office, west on Interstate 10. truck matching On Thursday, advising that there had been Deputies from the JCSO the description April 11, the a possible shooting on responded to Interstate 10 in of the suspect's Jefferson County Interstate 10, with the order to locate and vehicle drove past. Sheriff's Office involved persons heading stop the two Jefferson County (JCSO) arrested west into Jefferson County. vehicles. Sheriff's Deputies Harrison Mario Verasso after Verasso The victim had placed JCSO's Cpl. and Carey pursued and engaged in shooting at the original call, Ryland spotted the victim's stopped the suspect's truck another vehicle while advising that a vehicle and made a traffic and made contact with Mario traveling on Interstate 10 man in a dark stop around mile marker 217, Verasso. through Madison County. colored just inside the Jefferson In a post-Miranda Mario Anthony Verasso See SHOOTING page 3 On the above date, the Chevrolet pickup truck had County line. Noise Two arrested on fraud charges ordinance Secret Service to investigate federal charges in the making Ashley Hunter Jeep Wrangler after ECB Publishing, Inc. -

Overview Differentiation in Our Education

Bellevue Christian School - Overview Located near beautiful Seattle, Washington, Bellevue is known as the next Silicon Valley. Bellevue has a high concentration of numerous global corporate headquarters, including Amazon and Microsoft. Bellevue is a vibrant, modern and growing city that attracts highly educated, high income earners who specialize in tech and other industries. Accoladed for its safety and quality of residential and educational environment, Bellevue was ranked as the 2nd best place to live by USA Today in 2014. Bellevue Christian School is an independent nondenominational Christian school that has been providing Christ-centered learning for over 60 years. The school is nestled near the heart of downtown Bellevue – in a neighborhood that hosts world famous entrepreneurs such as Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos - and has gained a reputation for rigorous academics, warm community, strong Christian faith and the desire to see students achieve their very best inside and outside of the classroom. The school offers a comprehensive university preparatory curriculum in all disciplines including AP classes, various music programs, varsity sports, and dynamic clubs. Basics Admissions International Student Facts & Figures Founded 1950 Faith Requirement Open ELL Support Yes AP Classes 13 Grades P-12 Accept Mid-Year Yes Current Int’l Elem Students <10 Peer Tutoring Yes Accepting Grades K-12 Accept Seniors No % of Elem. Student Body 6% Average Class Size 21 Enrollment 950 Countries: China, Taiwan, Ethiopia, Current Int’l JH/HS Students <50 Teacher – Student Ratio 1:15 % of JH/HS Student Body JH/SH Enrollment 515 Korea, South Africa, Vietnam, 12% ACT/SAT Prep No EnGland, Germany, Thailand, Average SAT 1260 Philippines Average ACT 25 Differentiation in Our Education • Accredited School with CSI and NAAS • Small class size (1:15 Teacher Student Ratio) • Selective teacher qualification requirement (includes Doctorate holders and lecturers at local universities) • 13 AP Courses: English Literature and Composition, University and Career in Seattle World History, U.S. -

University of Montevallo Student Distance Education Handbook

Student Distance Education Handbook 2020-2022 1 https://www.montevallo.edu/academics/distance-education-um/ Table of Contents UM Distance Education .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Definitions................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Technical Recommendations ............................................................................................................................................... 4 University Commitment ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 Student Commitment .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 Guidelines .................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Acceptable Use Policy ......................................................................................................................................... 7 ADA Statement ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 Attendance in Distance Education -

2020-21 MANUAL NCAA General Administrative Guidelines

2020-21 MANUAL NCAA General Administrative Guidelines Contents Section 1 • Introduction 2 Section 1•1 Definitions 2 Section 2 • Championship Core Statement 2 Section 3 • Concussion Management 3 Section 4 • Conduct 3 Section 4•1 Certification of Eligibility/Availability 3 Section 4•2 Drug Testing 4 Section 4•3 Honesty and Sportsmanship 4 Section 4•4 Misconduct/Failure to Adhere to Policies 4 Section 4•5 Sports Wagering Policy 4 Section 4•6 Student-Athlete Experience Survey 5 ™ Section 5 • Elite 90 Award 5 Section 6 • Fan Travel 5 Section 7 • Logo Policy 5 Section 8 • Research 6 Section 9 • Division III 6 Section 9•1 Division III Philosophy 6 Section 9•2 Commencement Conflicts 6 Section 9•3 Gameday the DIII Way 7 Section 9•4 Religious Conflicts 7 THE NATIONAL COLLEGIATE ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION P.O. Box 6222 Indianapolis, Indiana 46206-6222 317-917-6222 ncaa.org November 2020 NCAA, NCAA logo, National Collegiate Athletic Association and Elite 90 are registered marks of the Association and use in any manner is prohibited unless prior approval is obtained from the Association. NCAA PRE-CHAMPIONSHIP MANUALS 1 GENERAL ADMINISTRATIVE GUIDELINES Section 1 • Introduction The Pre-Championship Manual will serve as a resource for institutions to prepare for the championship. This manual is divided into three sections: General Administrative Guidelines, Sport-Specific Information, and Appendixes. Sections one through eight apply to policies applicable to all 90 championships, while the remaining sections are sport specific. Section 1•1 Definitions Pre-championship Manual. Resource for institutions to prepare for the championship. Administrative Meeting. Pre-championship meeting for coaches and/or administrators. -

February 6, 2019

AUBURN UNIVERSITY OFF I CE O F T H E P R ES I DENT February 6, 2019 MEMORANDUM TO: Board of Trustees SUBJECT: February 14-15, 2019 Board of Trustees Workshop and Meeting Enclosed are materials that comprise the proposed agenda for the Thursday, February 14, 2019 workshop in Auburn, as well as the Friday, February 15, 2019 meeting in the Taylor Center on the AUM Campus. Listed below is the tentative schedule, times and meeting locations: Thursday, February 14, 2019 1:00 p.m. Workshop (Room 109, CASIC Building at the Research Park) (Potential Tour of the recently renovated Auburn Public Safety Building following the workshop, if time permits) Friday, February 15, 2019 (Rooms 222-223 Taylor Center, AUM Campus) 9:00 a.m. Property and Facilities Committee 9:30 a.m. Audit and Compliance Committee 9:45 a.m. Joint Academic Affairs and AUM Committees 10:00 a.m. Executive Committee 10:05 a.m. Trustee Reports 10:30 a.m. Regular Meeting of the Board of Trustees (222-223 Taylor Center) (Executive Session if needed - Chancellor's Dining Room, Taylor Center) We appreciate all that you do for Auburn University and look forward to seeing you on Thursday, February 14, 2019 on the Auburn campus in the CASIC Building and then on Friday, February 15, 2019, for the regular meeting in the Taylor Center on the AUM Campus. Please call me if you have questions regarding the agenda. Also, please let Jon G. Waggoner, Sherri Williams, or me know if you need assistance with travel and/or lodging arrangements. -

Tax Instructors

AUBURN UNIVERSITY 2021 TAX PROFESSIONAL SEMINAR: Instructor Team Christopher Bird, EA, CFP: Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, Instructor for live and online Chris Bird has been in the financial business for over 30 years. He started his career with a degree in Accounting and a minor in Business Administration. He also holds the Certified Financial Planner designation (CFP). Chris was a Senior IRS agent for 16 years. He began conducting courses after leaving the IRS and started his own company, Chris Bird Seminars, Inc. Chris went on to conduct over 125 seminars a year on accounting, financial planning, wealth building, residential rental property ownership, and tax strategies for the real estate and financial industries nationwide. He has presented his widely acclaimed courses multiple times at NAR conventions and most recently presented at Howard Brinton’s StarPower™ Conference. Chris was an adjunct instructor at the University of Illinois in tax law for over 20 years. He is a Senior CRS Instructor and a Senior Faculty Instructor for the Realtors Land Institute. And he also teaches at all the Illinois tax seminars currently using the National Income Tax Workbook also used in the Auburn University programs. Chris has a unique way of making a tough subject (taxation instruction) entertaining and enlightening for our audience. Michael Ferguson, CPA, CFP: Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, Instructor Michael Ferguson has over thirty years’ experience in accounting, tax, and financial planning for businesses and individuals. Currently his practice is located in Guntersville, Alabama, where he works with clients from all over the country. He owned a firm in metro Atlanta early in his career and returned to northeast Alabama in 1987. -

1976 Championship, Women's Basketball

SUNY College Cortland Digital Commons @ Cortland Women’s Basketball Documents Women's Basketball 1976 1976 Championship, Women's Basketball State University of New York College at Cortland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cortland.edu/womenbasketball_documents STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORTLAND, NEW YORK 13045 OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT The State University of New York College at Cortland is pleased to welcome the coaches, officials, participants and spectators to our campus for the EAIAW Northeast Basketball Championship. We trust your stay with us will be pleasant and that you will wish to come often. Good luck to all concerned. "" /) I :¥ j~ .Y,f',:.LJY... ~ J -r ~7--C"-'-"'- Richard C. Jones President The Women's Physical Education Department welcomes to the EAIAW I~ortlieastReoional Basketball Championshi p all those who love the game of basketball--an All-American Game if there ever was one: May the enthusiasm and excitement of the bicentennial year be reflected in each of us. Let the spirit of '76 be our motto as we strive to achieve all we are capable of being. %'tU'~~r -latherine Ley, Chalf!Jc,son Women's Physical Education EAIAW EXECUTIVE BOARD 1975-76 President Jeanne Snodgrass George Washington Univ. Past President Jessie Godfrey SUNY Binghamton President-Elect Carole Mushier SUC Cortland Treasurer De11a Durant Pennsylvania State U. Membership Secretary Elizabeth Darling SUC Fredonia Recording Secretary Lee Rhenish SUNY Albany Members at Large Northeast PaulaHodgdon U. of Maine, Portland-G. Carolyn Lehr -

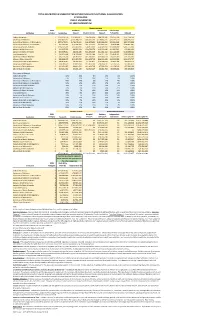

Total Restricted & Unrestricted Expenditures

TOTAL RESTRICTED & UNRESTRICTED EXPENDITURES BY FUNCTIONAL CLASSIFICATION FY 2018-2019 PUBLIC UNIVERSITIES BY SREB CATEGORY (a) Student-focused SREB Academic Institutional Scholarship/ Institution Category Instruction Support Student Service Support Fellowship Subtotal Auburn University 1 $252,146,479 $134,846,851 $40,706,539 $89,204,046 $20,255,248 $537,159,163 University of Alabama 1 $361,807,147 $113,368,673 $66,981,218 $120,146,275 $26,259,220 $688,562,533 University of Alabama at Birmingham 1 $297,179,571 $176,175,511 $44,287,689 $152,386,829 $29,041,268 $699,070,868 University of Alabama in Huntsville 2 $71,302,241 $13,098,268 $21,213,673 $21,887,215 $3,474,084 $130,975,481 University of South Alabama 2 $139,221,000 $32,963,000 $48,454,000 $50,924,000 $13,990,000 $285,552,000 Alabama A & M University 3 $32,957,353 $8,533,583 $20,578,573 $16,309,940 $21,302,543 $99,681,992 Jacksonville State University 3 $47,659,611 $8,188,248 $21,295,563 $21,042,122 $12,148,000 $110,333,544 Troy University (c) 3 $82,325,908 $18,419,690 $36,791,489 $46,242,715 $25,858,792 $209,638,594 University of North Alabama 3 $45,374,378 $6,369,952 $11,598,392 $19,046,073 $9,069,020 $91,457,815 Alabama State University 4 $39,655,073 $12,487,990 $16,109,713 $36,291,965 $18,929,986 $123,474,727 Auburn University at Montgomery 4 $30,454,417 $4,496,303 $7,786,835 $14,209,874 $3,416,324 $60,363,753 University of Montevallo 5 $28,583,870 $7,843,097 $13,163,709 $10,906,672 $4,349,576 $64,846,924 University of West Alabama 5 $32,151,487 $6,141,629 $11,164,796 $7,000,033 -

Four-Year Colleges Fielding Softball Teams (U.S. and Canada)

Four-Year Colleges Fielding Softball Teams (U.S. and Canada) 101 102 COLLEGE LISTINGS U.S. AND CANADIAN COLLEGES FIELDING SOFTBALL TEAMS The following information is designed to help you start identifying the colleges you want to contact. For each school I’ve listed the name and address; whether the school is public or private; the size; the setting; religious affiliation if applicable; an approximate cost for tuition/fees and housing; whether softball scholarships are offered; the school’s athletic affiliation; and the softball coach’s name and phone number. The listings are alphabetical by state and school. Here’s what a typical listing looks like: College name –––– Coastal Carolina University Box 1954 –––– Mailing address Conway, SC 29526 Public or private school; size; setting –––– Public, Small, Suburban $10360/17540/incl, Yes, NCAA-I –––– Estimated cost for in-state/out-of-state Softball coach’s name & phone number –––– Jess Dannelly 843-349-2827 tuition/fees and housing; whether or not softball scholarships are offered; athletic affiliation email address –––– [email protected] NOTES: • For the school size, “Small” means 6000 or fewer students; “Medium” means 6000 - 12000 students; and “Large” means more than 12000 students. • “Metro” indicates the school is located in a major metropolitan area; “suburban” means it’s in either a small town or a suburban area; and “rural” means it’s in a rural area. • The amounts by the dollar sign ($) represent estimated in-state and out-of-state tuition/fees plus housing costs based on 2007-08 figures. In most cases, the listed amount will not include the cost of books, travel, personal expenses, etc. -

FACULTY Dates Listed in Parentheses Indicate Year of Tenure-Track Appoint- Chiara D

FACULTY Dates listed in parentheses indicate year of tenure-track appoint- Chiara D. Bacigalupa (2007) ment to Sonoma State University. Associate Professor, Literacy, Elementary, and Early Education List as of September 26, 2014 B.A. 1987, University of California, Santa Cruz M.A. 1991, California State University, Northridge Judith E. Abbott (1991) Ph.D. 2005, University of Minnesota Professor, History B.A. 1970, University of Minnesota Christina N. Baker (2008) M.A. 1977, Ph.D. 1989, University of Connecticut Associate Professor, American Multicultural Studies B.A. 2000, University of California, Los Angeles Emily E. Acosta Lewis (2013) M.A. 2003, Ph.D. 2007, University of California, Irvine Assistant Professor, Communication Studies B.A. 2005, California State University, San Diego Jeffrey R. Baldwin (2009) M.A. 2008, Ph.D. 2012, University of Wisconsin-Madison Associate Professor, Geography and Global Studies B.A. 1979, M.A. 1998, Ph.D. 2003, University of Oregon Theresa Alfaro-Velcamp (2003) Professor, History Melinda C. Barnard (1990) B.A. 1989, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo Associate Vice President for Faculty Affairs, M.S. 1990, London School of Economics and Political Science and Chief Research Officer M.A. 1995, Ph.D. 2001, Georgetown University Professor, Communication Studies B.A. 1975, Ph.D. 1986, Stanford University Ruben Armiñana (1992) M.A. 1976, Harvard University President, Sonoma State University; Professor, Political Science A.A. 1966, Hill College Edward J. Beebout (2007) B.A. 1968, M.A. 1970, University of Texas at Austin Associate Professor, Communication Studies Ph.D. 1983, University of New Orleans B.A. 1981, Humboldt State University M.S. -

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST