Speculations on History's Futures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queensland Art Gallery

Nationally Significant 20th-Century Architecture Revised date 27/05/2011 Queensland Art Gallery Address Stanley Place, South Bank, Brisbane , Qld Practice Robin Gibson & Partners Designed 1973 Completed 1982 History & Located southwest of the Brisbane CBD, overlooking Queen Description Elizabeth II Park to the northeast & the Brisbane River beyond, the Queensland Art Gallery was the first building designed in the extensive Queensland Cultural Centre. The gallery originated from a limited competition in 1973. Soon after, in 1975, the state government resolved to construct the much larger integrated Queensland Cultural Centre & to include a performing arts centre, museum & library. The site, adjacent to the busy Grey Street & South east view towards entry. railway line to the south west, was extended along the river bank. The complex of three buildings was designed by Robin Gibson in conjunction with the Queensland Department of Works. The gallery, constructed externally & internally in bush-hammered off-white insitu concrete, has a stepped horizontal form opening out to the river & the view of the city to the north east while turning its back to Grey Street. The horizontal theme is enhanced with extended planting along the ‘terraces’ & the longitudinal water feature, the Water Mall, which crosses the site, extending through & beyond the building. Water is introduced as a series of audible & kinetic elements externally, which contrasts with the more placid setting of the three-level high central interior space of the Water Mall. This impressive three-dimensional central space separates the galleries from the administration, education & library areas & is South view along Water Mall. naturally lit through a glazed roof supported by ‘pergola like’ pre- Source: R. -

QUEENSLAND CULTURAL CENTRE Conservation Management Plan

QUEENSLAND CULTURAL CENTRE Conservation Management Plan JUNE 2017 Queensland Cultural Centre Conservation Management Plan A report for Arts Queensland June 2017 © Conrad Gargett 2017 Contents Introduction 1 Aims 1 Method and approach 2 Study area 2 Supporting documentation 3 Terms and definitions 3 Authorship 4 Abbreviations 4 Chronology 5 1 South Brisbane–historical overview 7 Indigenous occupation 7 Penal settlement 8 Early development: 1842–50 8 Losing the initiative: 1850–60 9 A residential sector: 1860–1880 10 The boom period: 1880–1900 11 Decline of the south bank: 1900–1970s 13 2 A cultural centre for Queensland 15 Proposals for a cultural centre: 1880s–1960s 15 A new art gallery 17 Site selection and planning—a new art gallery 18 The competition 19 The Gibson design 20 Re-emergence of a cultural centre scheme 21 3 Design and construction 25 Management and oversight of the project 25 Site acquisition 26 Design approach 27 Design framework 29 Construction 32 Costing and funding the project 33 Jubilee Fountain 34 Shared facilities 35 The Queensland Cultural Centre—a signature project 36 4 Landscape 37 Alterations to the landscape 41 External artworks 42 Cultural Forecourt 43 5 Art Gallery 49 Design and planning 51 A temporary home for the Art Gallery 51 Opening 54 The Art Gallery in operation 54 Alterations 58 Auditorium (The Edge) 61 6 Performing Arts Centre 65 Planning the performing arts centre 66 Construction and design 69 Opening 76 Alterations to QPAC 79 Performing Arts Centre in use 80 7 Queensland Museum 87 Geological Garden -

Queensland Cultural Centre Conservation Management Plan

QUEENSLAND CULTURAL CENTRE CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN Background CMP development and consultation In 2015, some of the original buildings of the The CMP was developed by a team of specialist Queensland Cultural Centre on the Cultural heritage consultants led by Brisbane-based Precinct at South Brisbane were heritage listed architectural practice Conrad Gargett and in clearly demonstrating its historic, rare, cultural, consultation with the Queensland Premier’s aesthetic, technical and social significance. The Cultural Precinct Design and Heritage nomination for heritage listing received 1254 Roundtable, established to provide independent public submissions – an exceptional result advice throughout development of the CMP. for a single nomination in the history of the Extensive consultation was undertaken in the Queensland Heritage Act. development of the CMP, including engagement The heritage listing includes the original with key industry body the Australian Institute of buildings and integrated landscape design by Architects, other key stakeholders and through a the late Robin Gibson AO for the Queensland period of public consultation during January and Art Gallery, Queensland Museum, Queensland February 2017. Performing Arts Centre and The Edge at the State Library of Queensland built in stages from 1976. CMP methodology and key elements The CMP uses the method of investigation and Queensland Cultural Centre Conservation analysis established by the Burra Charter, an Management Plan (CMP) internationally endorsed standard for heritage The CMP, commissioned by Arts Queensland, conservation practice. provides a framework to understand and manage The Burra Charter emphasises the importance of the Cultural Centre’s heritage values, guide future a logical and systematic approach to undertaking infrastructure planning and ensure it thrives and a plan for conserving heritage places by outlining adapts into the future. -

AMICUS March 2021Vol 49 No 1 Journal of the BSHS Past Students’ Associa�On Inc

AMICUS March 2021Vol 49 No 1 Journal of the BSHS Past Students’ Associa�on Inc. GRADUATION 2020 A high energy celebration farewelled the 2020 Year 12 graduates who, in 2016, were the first cohort to commence secondary school in Year 7. Amanda Newbery (O’Chee), Class of 1990, dispensed some sage advice with a good dose of common sense on how to han- dle the opportunities that will arise in the future. As in previous years the graduation certificates were presented by past BSHS school cap- tains viz. Graeme Payne, 1960, Christine Grimmer and Otto Lechner, 1970, Jackie Witham and Lionel Hogg 1980, Nick Denham 2000, Cecelia Redfern and Dr Tom Wil- liams 2010. Cecelia and Tom assumed the MC duties. Executive Principal Wade Haynes reiterated that “Knowledge is Power” and advised the graduating class to use the school’s motto to their advantage to have an impact as they embark on the next stage of their development. CENTENARY LAUNCH On 29 January, State High’s Centenary was launched on the Kurilpa Roof Terrace, at- tended by distinguished guests, past students, staff and 2021 student leaders. Fourth generation State High student, Jade Bartholomeusz (Year 10), spoke of her fami- ly's significant history at our school, starting with her great grandmother Audrey Lis- combe (Smith), Class of 1931, Jade's grandfather Everard Bartholomeusz, Class of 1964, father Mark Bartholomeusz, Class of 1994, and family who attended this special occasion. CENTENARY PROGRAM 31 March Senior’s Morning Tea BSHS A Foundation event 23 April ANZAC Day Ceremony BSHS 4 July “Tour of State High” BSHS A BSHS PSA event 31 July State High Day BSHS A BSHS P and C event 19 July Foundation Day Assembly Brisbane Convention Centre September Centenary Showcase QPAC 15 October State High Golf Masters St Lucia A Foundation event Additional information and registration is available at: www.bshs100.com.au Register on www.statehighconnect.com.au to view all school magazines from 1921. -

Concrete Expressions Brutalism and the Government Buildings Precinct, Adelaide

CONCRETE EXPRESSIONS BRUTALISM AND THE GOVERNMENT BUILDINGS PRECINCT, ADELAIDE Kevin O’Sullivan Architecture Museum School of Architecture and Design University of South Australia Architecture Museum Monograph Series 07 O’Sullivan, Kevin. Concrete Expressions: Brutalism and the Government Buildings Precinct, Adelaide Contents First published in 2013 in Australia by the School of Art, Architecture and Design, 2 Foreword University of South Australia, 6 Introduction Adelaide, South Australia 4 Acknowledgements Series Editors: Christine Garnaut and Julie Collins 8 Background to Brutalism © Kevin O’Sullivan 18 Brutalism in Australia ISBN 978-0-9871200-4-5 24 The Government Buildings Precinct Monograph design: Jason Good and Leah Zahorujko 38 Buildings and Precinct Analysis Design direction: Fred Littlejohn School of Art, Architecture and Design, University of South Australia 42 Architectural Influences Print: Graphic Print Group Adelaide, South Australia 44 Conclusion 46 Endnotes Copies available from: Dr Christine Garnaut 50 Further reading Director, Architecture Museum School of Art, Architecture and Design 54 About the Author University of South Australia 56 About the Architecture Museum GPO Box 2471 Adelaide, South Australia 5001 Cover illustration: ‘P.B.D. in Tower of Strength’, Perspective: Public Buildings Department Journal, vol.3, no. 2, 1978, p. 19. Unless otherwise credited all illustrations are from the Architecture Museum’s own collections. All reasonable efforts have been made to trace the copyright holders of all images reproduced -

UQ Centenary Map: Improvement Around and Between Buildings

1910-1949 committee’s desires for the campus these words were well chosen. Effectively the architects had Smith building (administration, arts and law), the first two stories of the Duhlg library, and the Steele 1970 1980 architecture could contribute positive outdoor spaces to the campus, enhancing the relationship founding Hennessy Hennessy & Co plan. New thinking was required in facing up to a looming problem. NOTES dispensed with the strict quadrangle form favoured by the committee and replaced It with a grander building (chemistry) were the only buildings whose construction was completed at the opening. Two between buildings, their users and the campus landscape, The first project was the Therapies and The university sought further sites to develop on a campus that was already seen as filling up with 1 Pay! Venable Turner, Campus: An American Planning Tradition (Cambridge. Mass.: MIT Press, 1984). 167 \ 2 Malcolm CREATING THE GREAT COURT: The architectural and urban centerpiece of the St Lucia Campus - By the end of the 1960s, the perceived lack of space and the Increasing amount of vehicle traffic Through the 1980s the numbers of students attending university steadily grew and UQ continued its I Thornis, A Place of Light & Learning; The University of Queensland's First Seventy-Five Years (St. Lucia: University of Anatomy Building Stage 3. What might seem a relatively modest proposal today was actually a buildings. How could the university effectively plan for the development of its land without adversely UQ’s famous Great Court - clearly defines the University as a place. Its enclosing space makes a more open space. -

602800 Spring Hill Fulton & Collin Architects Office (Former) 96 Astor

Submission HRN: 602800 Spring Hill Fulton & Collin Architects Office (former) 96 Astor Terrace Corporate details ´ Quality assurance ´ Architect 3rd Party Accreditation from Fulton Trotter and Partners Benchmark Certification Architects Pty Ltd Standard AS/NZS ISO 9001:2000 Benchmark Certification Certificate Number: FS520602 ´ Practice Trading as: Fulton Trotter Architects ´ Professional indemnity Insurer: Allianz Policy Number: 141A000206PLP Sum Insured: $10,000,000 ´ ABN 88 342 546 315 Valid to: 31/03/2013 ´ ACN 110 065 619 ´ Public liability Insurer: QBE Insurance Limited ´ The Trustee for FTPA (AA) Trust & Policy Number: 70F780843BPK The Trustee for FTPA (GI) Trust & Sum Insured: $10,000,000 The Trustee for FTPA (MT) Trust & Valid to: 01/03/2013 The Trustee for FTPA (PT) Trust & The Trustee for FTPA (RW) Trust ´ Copyright © 2012 Fulton Trotter and Partners Architects Pty Ltd trading as ´ Nominated architects Fulton Trotter Architects Mark Trotter This document, its text, QLD 1870 NSW 4421 VIC 17691 photographs and drawings remain the property of Fulton ´ Paul Trotter Trotter Architects. All information in QLD 2646 NSW 7177 this document is strictly confidential. ´ Prequalification New South Wales Government Department of Finance & Services Queensland Government Level 3 a) The Place is important in demonstrating the evolution of Queensland’s History This building was the home of one of Queensland’s oldest and most established Architectural Practices from 1960 to 1990 and from 2001 to 2011. Charlie Fulton and Jim Collin the original owners and founding partners both commissioned and worked in the building over many years. Charlie Fulton is a famous figure in Queensland architectural circles and his influence is significant in terms of his roles as Head of the School of Architecture at QUT for some 40 years and twice president of the Queensland Chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects. -

QAG Architecture, Artlines, 1, 2018

QAG'S ARCHITECTURAL EVOLUTION 31 AN OFFER OF LIGHT AND AIR QAG’S ARCHITECTURAL EVOLUTION At a time when most Australian galleries were temple-like buildings that upheld the exclusivity of art appreciation, architect Robin Gibson’s Queensland Art Gallery was truly extraordinary: through the language of Modernism, Gibson’s intention was to democratise art and bring it to the people. Louise Martin-Chew spoke with QAGOMA Director Chris Saines on his plans for the building. The Queensland Art Gallery is arguably the the international collection, and for the vista most successful building designed by architect to the fountain outside. Heritage listing of the Robin Gibson AO (1930–2014), and was widely entire Gibson-designed Cultural Centre in 2015 admired when it opened in 1982 — Gibson added an additional imperative to this work, but received the prestigious Sir Zelman Cowen for Saines, the incentive to restore QAG lies in Award for Public Architecture that same enhancing enjoyment of its collections and the year. It was visionary for its time, and Gallery unique nature of the place: Director Chris Saines remains impressed by Gibson’s foresight, his ability to design As a visitor to this gallery, you were originally for functionality as well as the quality of his offered connections to the city, then you moved aesthetic vision. ‘The beauty and legibility into the gallery and the Watermall, which is of this building’, he says, ‘is a product of flooded with light. Gibson’s building speaks Gibson’s relentless application of an organising to the Brisbane River, with the Watermall in principle. -

90Th Anniversary Issue

FRYER 90th Anniversary Issue Volume 11 | Number 1 | November 2017 ISSN 1834-1004 FRYER Fryer Library, The University of Queensland Volume 11 | Number 1 | November 2017 INTRODUCTION 3 Simon Farley RG CAMPBELL’S ‘THE AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL STORY BOOK’ 4 Roger Osborne BEYOND THE ‘ROCKTON’ WINDOW: HELEN HAENKE REMEMBERED 8 Helen Pullar ‘GIVE MY LOVE TO EVERYONE’: THE FRYER BROTHERS OF SPRINGSURE 14 Melanie Piddocke FORGOTTEN STORIES: THE LOST HISTORY OF AUSTRALIANS IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA 18 Ian Townsend LILLA WATSON, ARTIST, UNIVERSITY LECTURER IN SOCIAL WORK 21 Matt Foley BRISBANE’S GOLD MEDAL MODERNIST: ROBIN GIBSON (1930–2014) 22 Robert Riddel LIBRARIES, LABYRINTHS, AND CRYSTAL CAVES 26 Darren Williams Fryer Folios is published by The University of Queensland Library to illustrate the range of special collections in the A WEIGHT OF LEARNING: Fryer Library and to showcase scholarly research based on these sources. ISSN 1834-1004 (print) ISSN 1834- THE HAYES COLLECTION 50 YEARS ON 30 1012 (online). Fryer Folios is distributed to libraries and Simon Farley educational institutions around Australia. If you wish to be added to the mailing list, please contact WHAT’S NEW IN FRYER LIBRARY 36 The University of Queensland Library, Belinda Spinaze The University of Queensland Q 4072. Telephone (07) 3365 6315; Email: [email protected] DIGITISATION UPDATE 40 Unless otherwise stated, the photographs in this journal are Elizabeth Alvey taken by the Digitisation Service. The views expressed in Fryer Folios are those of the individual contributors and do OBITUARIES: ERROL O’NEILL, CONNIE HEALY, not necessarily reflect the views of the editors or publisher. -

Report of the Queensland Art Gallery Board of Trustees

REPORT OF THE QUEENSLAND ART GALLERY BOARD OF TRUSTEES FOR THE PERIOD 1 JULY 2005 TO 30 JUNE 2006 PURPOSE OF REPORT In pursuance of the provisions of the Queensland Art Gallery This Annual Report documents the Gallery’s activities, Act 1987 s 53, the Financial Administration and Audit Act initiatives and achievements during 2005–06, and shows 1977 s 46J, and the Financial Management Standard 1997 how the Gallery met its objectives for the year and addressed Part 6, the Queensland Art Gallery Board of Trustees government policy priorities. This comprehensive review forwards to the Minister for Education and Minister for the demonstrates the diversity and significance of the Gallery’s Arts its Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2006. activities, and the role the Gallery plays within the wider community. It also indicates direction for the coming year. The Gallery welcomes comments on the report and suggestions for improvement. Wayne Goss, Chair of Trustees We encourage you to complete and return the feedback form in the back of this report. CONTENTS Masami Teraoka 05/ GALLERY PROFILE Japan/United States b.1936 McDonald’s Hamburgers Invading Japan/Chochin-me 1982 06/ HIGHLIGHTS AND ACHIEVEMENTS 36 colour screenprint on Arches 88 paper, ed. 41/91, 54.3 x 36.5cm (comp.) 09/ CHAIR’S OVERVIEW Purchased 2005. The Queensland Government’s Gallery of Modern Art 11/ DIRECTOR’S OVERVIEW Acquisitions Fund COVER: 13/ QUEENSLAND ART GALLERY | GALLERY OF MODERN ART ‘TWO SITES, ONE VISION’ The Gallery of Modern Art under construction, 2006 17/ COLLECTION -

John Dalton's 1970S Campus

Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians Australia and New Zealand Vol. 32 Edited by Paul Hogben and Judith O’Callaghan Published in Sydney, Australia, by SAHANZ, 2015 ISBN: 978 0 646 94298 8 The bibliographic citation for this paper is: Musgrave, Elizabeth. “Structuring Space for Student Life: John Dalton’s 1970s Campus Commissions.” In Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 32, Architecture, Institutions and Change, edited by Paul Hogben and Judith O’Callaghan, 446-456. Sydney: SAHANZ, 2015. All efforts have been undertaken to ensure that authors have secured appropriate permissions to reproduce the images illustrating individual contributions. Interested parties may contact the editors. Elizabeth Musgrave, University of Melbourne and University of Queensland Structuring Space for Student Life: John Dalton’s 1970s Campus Commissions This paper investigates the way in which a rethinking of pedagogical philosophies during the 1960s and 1970s might have informed the architecture of the educational institutions themselves. It will describe four projects from the office of John Dalton Architect and Associates on campuses of higher education in South East Queensland that resulted from the rapid expansion of the sector in the 1960s in Australia and that embody the spirit of innovation within the sector at that time. These works – which include the Art, Craft and Music Teaching Building (1970-74) at the Darling Downs Institute of Advanced Education; University House (1972) at Griffith University, Campus Nathan; the Halls of Residence at Kelvin Grove Teachers Training College (1974); and the Bardon Professional Development Centre (1975) – explore architectural solutions for models of education introduced into Queensland in the 1970s and reveal Dalton’s interest in place, in the idea of community and in the capacity of architectural form to structure social and educational interactions. -

HCA12UQ120517.Pdf

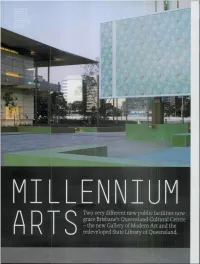

Two very different new public facilities now grace Brisbane's Queensland Cultural Centre - the new Gallery of Modern Art and the redeveloped State Library of Queensland. STATE 0 E ARTS qualities. The screw of this little paradox turns more tightly for architects What makes a public building? who know that the form of the building and particularly the flying roof and the box-like irregular protrusions are greatly inspired by Jean Nouvel's John Macarthur reflects on Lucerne Cultural and Congress Centre. Does it matter that the public don't differing perceptions and know that the identifications with the local that they desire are actually a part of highly internationalized architectural discourse? Certainly the Clares' constructions of the public realm. design achieves this double take of speaking to the popular expectation of buildings while also developing their own clever response to the protruding roof and deep shadow line that interests a whole section of the intemational ueensland's Millennium Arts projects have opened to great public and architecture scene. Are these two levels of engagement articulated at GoMA? Q professional acclaim. The extension to the State Library, by Donovan Hill Should they be? I'm not sure, but something like an attempt at a thorough with Peddle Thorp, and the Gallery of Modem Art addition to the Queensland articulation of architectural discourse with the local is going on at the library. Art Gallery, by Architectus, are the most interesting public buildings to be Unfortunately, it doesn't seem to be working wonderfully well from the completed in 2006 in Australia, and the most prominent in Queensland since public point of view.