“In recent years, in region after region, we have found that our diplomacy has been influenced by success or failure in managing the environment. This shouldn’t surprise us. After all, competition for scarce resources is an ancient source of human conflict. In our day, it can still elevate tensions among countries or cause ruinous violence within them…..By definition the global environment deeply affects our own people.”

Madeleine Albright Press Remarks on Earth Day April 22, 1997

US- Canadian Transboundary Water Issues

HISTORY and GEOGRAPHY

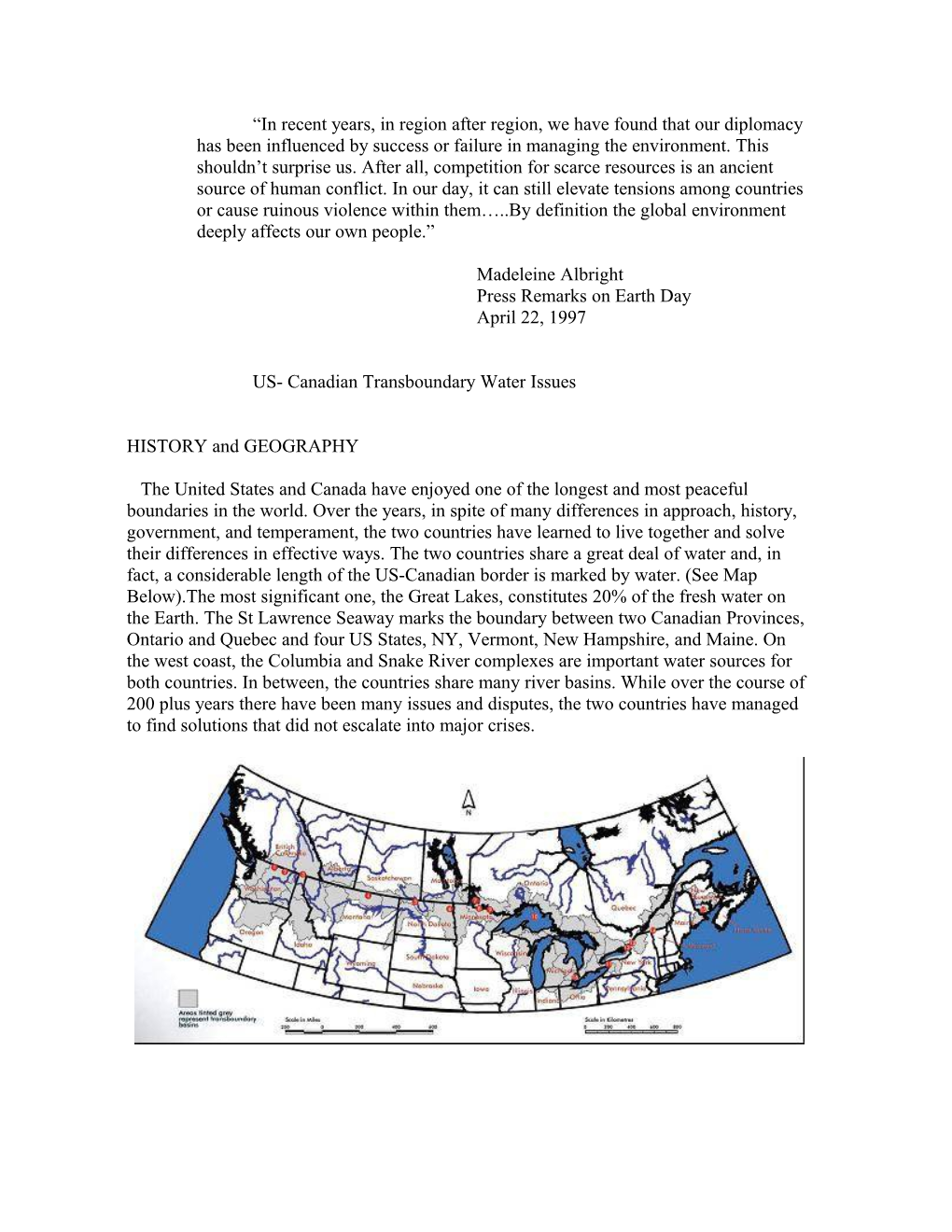

The United States and Canada have enjoyed one of the longest and most peaceful boundaries in the world. Over the years, in spite of many differences in approach, history, government, and temperament, the two countries have learned to live together and solve their differences in effective ways. The two countries share a great deal of water and, in fact, a considerable length of the US-Canadian border is marked by water. (See Map Below).The most significant one, the Great Lakes, constitutes 20% of the fresh water on the Earth. The St Lawrence Seaway marks the boundary between two Canadian Provinces, Ontario and Quebec and four US States, NY, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. On the west coast, the Columbia and Snake River complexes are important water sources for both countries. In between, the countries share many river basins. While over the course of 200 plus years there have been many issues and disputes, the two countries have managed to find solutions that did not escalate into major crises. THE BOUNDARY WATERS TREATY OF 1909

In 1909, the US and Canada negotiated a formal treaty and develop a diplomatic process to address boundary water issues between them. The treaty established the International Joint Commission, a binational organization whose purpose is to “provide the principles and mechanisms to help prevent and resolve disputes, primarily those concerning water quantity and water quality along the boundary between Canada and the United States.” In 1972, the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement was added. Its purpose affirmed “the commitment of each country to restore and maintain the chemical, physical and biological integrity of the Great Lakes basin ecosystem.” The Commission itself consists of 6 members, three from each country. The commissioners do not represent their individual countries. Rather they are charged with acting as a single body whose task it is to seek common solutions that benefit all the stakeholders of the region.

The Commission has designated 16 local boards of control to assist it in its tasks. These boards are:

1. International Osoyoos Lake Board of Control 2. International Columbia River Board of Control 3. International Kootenay Lake board of Control 4. St Mary-Milk Rivers Accredited Officers 5. International Souris River Board 6. International Red River Board 7. International Lake of the Wood Board of Control 8. International Rainey River Water Pollution Board 9. International Rainey Lake Board of Control 10. International Lake Superior Board of Control 11. International Niagara Board of Control 12. International St Lawrence River Board of Control 13. International Lake Ontario-St Lawrence River Study Board 14. International Missisquoi Bay Task Force 15. International St. Croix River Board 16. Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement Boards

These boards, consisting of local experts operated regionally, carry on the studies and field work required to meet their charter.

Responsibilites

The IJC has three principle responsibilities:

1. The Commission gives approval to projects and uses of water (called Applications) that would obstruct or divert waters that flow along the border if such uses affect the natural water levels or flows on either side.

2. When asked to do so by both countries, the Commission conducts studies and investigations (called References) of specific issues. Recommendations of the Commission are voluntary and require further actions by the two governments.

3. The treaty also allows binding decisions by the Commission, but to date, there have been no such referrals.

In addition to the formal responsibilities, the Commission is to keep the public involved in the decision making progress. It does so by conducting frequent public meetings along the boundary. Each Board normally conducts one public meeting on each side of the border yearly.

ISSUES

Navigation. The St Lawrence Seaway and the Soo Locks (Between Lake Superior and Michigan) are outdated structures that limit navigation on the Great Lakes to 1000 foot vessels. Modern ocean going ships exceed this capacity and require costly and time consuming transloading.

Ecosystem Analysis. The treaty was negotiated in 1909 and environmental concerns were not predominate at that time. The IJC has recommended that it be allowed to establish watershed boards to view their responsibilities in a more holistic manner.

Water Quality and Quantity. The need for safe and clean water has grown as populations and users make greater demands on water along the boundary. The Commission believes it must study water quantity and quality issues, to include air quality and make appropriate recommendations.

Governing Levels and Flows. The rules for water flow and levels were established before significant new riparian placed claims on the boundary waters. In addition to ecosystem demands, recreation users have a greater stake in allocation decisions.

Decommissioning Nuclear Reactors. The IJC feels that the ongoing decommissioning of nuclear reactors, many along the Great Lakes, poses special problems and hazards. There exists a growing need to study the impacts of these decommissionings on transboundary water issues.

Biennial Reports. The Commission feels that it must achieve great awareness of transboundary water issues. It recommends biennial reports to cabinet level officials of the respective governments. Devil’s Lake.

Devil’s Lake is a large body of water in North Dakota that has no outlet. Consequently, it has accumulated a great deal of pollutants and is highly saline. For the last 60 years it has been rising and within a few years threatens to overflow into the Sheyenne River, which flows into the Red River and subsequently into Canada. The State desires to build an outlet to control an overflow and protect surrounding communities. The Army Corps of Engineers has studied the possibility of an outlet and Canada has pursued an outlet of its own. (See US Army Feasibility Report). Canada has protested and requested a reference for study by the IJC. To date the US has not reciprocated and as a result the IJC has unable to assist in the issue.

References

Required Reading (See course syllabus)

“The IJC and the 21st Century” Published by the International Joint Commission October 21 1997

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Feasibility Study “Devil’s Lake”

ISSUES FOR DISCUSSION

1. The US and Canada have enjoyed a long and peaceful history. The institutions they have set up seem to have worked well in this setting. How does the configuration of the IJC differ from those we have seen in less developed regions?

2. The IJC works primarily in a collaborative way and is largely advisory in nature. How does this facilitate or hinder decision making? Will this work as water problems grow increasingly complex and stakeholders expand and become more demanding?

3. How are the interests and issues of new stakeholders addressed by older deliberative bodies such as the IJC? Can they adapt to changing circumstances and still retain legitimacy?

4. Given the case study of Devil’s Lake, how has the IJC worked in resolving this issue? What does this tell us about institutions such as the IJC? Does it argue for fundamental changes in decision making procedures?