4Th Edition of the Handbook of Statistical Organization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Participants

List of participants Conference of European Statisticians 69th Plenary Session, hybrid Wednesday, June 23 – Friday 25 June 2021 Registered participants Governments Albania Ms. Elsa DHULI Director General Institute of Statistics Ms. Vjollca SIMONI Head of International Cooperation and European Integration Sector Institute of Statistics Albania Argentina Sr. Joaquin MARCONI Advisor in International Relations, INDEC Mr. Nicolás PETRESKY International Relations Coordinator National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC) Elena HASAPOV ARAGONÉS National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC) Armenia Mr. Stepan MNATSAKANYAN President Statistical Committee of the Republic of Armenia Ms. Anahit SAFYAN Member of the State Council on Statistics Statistical Committee of RA Australia Mr. David GRUEN Australian Statistician Australian Bureau of Statistics 1 Ms. Teresa DICKINSON Deputy Australian Statistician Australian Bureau of Statistics Ms. Helen WILSON Deputy Australian Statistician Australian Bureau of Statistics Austria Mr. Tobias THOMAS Director General Statistics Austria Ms. Brigitte GRANDITS Head International Relation Statistics Austria Azerbaijan Mr. Farhad ALIYEV Deputy Head of Department State Statistical Committee Mr. Yusif YUSIFOV Deputy Chairman The State Statistical Committee Belarus Ms. Inna MEDVEDEVA Chairperson National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus Ms. Irina MAZAISKAYA Head of International Cooperation and Statistical Information Dissemination Department National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus Ms. Elena KUKHAREVICH First Deputy Chairperson National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus Belgium Mr. Roeland BEERTEN Flanders Statistics Authority Mr. Olivier GODDEERIS Head of international Strategy and coordination Statistics Belgium 2 Bosnia and Herzegovina Ms. Vesna ĆUŽIĆ Director Agency for Statistics Brazil Mr. Eduardo RIOS NETO President Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE Sra. -

UNWTO/DG GROW Workshop Measuring the Economic Impact Of

UNWTO/DG GROW Workshop Measuring the economic impact of tourism in Europe: the Tourism Satellite Account (TSA) Breydel building – Brey Auditorium Avenue d'Auderghem 45, B-1040 Brussels, Belgium 29-30 November 2017 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Title First name Last name Institution Position Country EU 28 + COSME COUNTRIES State Tourism Committee of the First Vice Chairman of the State Tourism Mr Mekhak Apresyan Armenia Republic of Armenia Committee of the Republic of Armenia Trade Representative of the RA to the Mr Varos Simonyan Trade Representative of the RA to the EU Armenia EU Head of balance of payments and Ms Kristine Poghosyan National Statistical Service of RA Armenia foreign trade statistics division Mr Gagik Aghajanyan Central Bank of the Republic of Armenia Head of Statistics Department Armenia Mr Holger Sicking Austrian National Tourist Office Head of Market Research Austria Federal Ministry of Science, Research Ms Angelika Liedler Head of International Tourism Affairs Austria and Economy Department of Tourism, Ministry of Consultant of Planning and Organization Ms Liya Stoma Sports and Tourism of the Republic of Belarus of Tourism Activities Division Belarus Ms Irina Chigireva National Statistical Committee Head of Service and Domestic Trade Belarus Attachée - Observatoire du Tourisme Ms COSSE Véronique Commissariat général au Tourisme Belgium wallon Mr François VERDIN Commissariat général au Tourisme Veille touristique et études de marché Belgium 1 Title First name Last name Institution Position Country Agency for statistics of Bosnia -

Celebrating the Establishment, Development and Evolution of Statistical Offices Worldwide: a Tribute to John Koren

Statistical Journal of the IAOS 33 (2017) 337–372 337 DOI 10.3233/SJI-161028 IOS Press Celebrating the establishment, development and evolution of statistical offices worldwide: A tribute to John Koren Catherine Michalopouloua,∗ and Angelos Mimisb aDepartment of Social Policy, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, Athens, Greece bDepartment of Economic and Regional Development, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, Athens, Greece Abstract. This paper describes the establishment, development and evolution of national statistical offices worldwide. It is written to commemorate John Koren and other writers who more than a century ago published national statistical histories. We distinguish four broad periods: the establishment of the first statistical offices (1800–1914); the development after World War I and including World War II (1918–1944); the development after World War II including the extraordinary work of the United Nations Statistical Commission (1945–1974); and, finally, the development since 1975. Also, we report on what has been called a “dark side of numbers”, i.e. “how data and data systems have been used to assist in planning and carrying out a wide range of serious human rights abuses throughout the world”. Keywords: National Statistical Offices, United Nations Statistical Commission, United Nations Statistics Division, organizational structure, human rights 1. Introduction limitations to this power. The limitations in question are not constitutional ones, but constraints that now Westergaard [57] labeled the period from 1830 to seemed to exist independently of any formal arrange- 1849 as the “era of enthusiasm” in statistics to indi- ments of government.... The ‘era of enthusiasm’ in cate the increasing scale of their collection. -

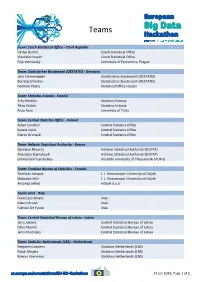

European Big Data Hackathon

Teams Team: Czech Statistical Office - Czech Republic Václav Bartoš Czech Statistical Office Vlastislav Novák Czech Statistical Office Filip Vencovský University of Economics, Prague Team: Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) - Germany Jana Emmenegger Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) Bernhard Fischer Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS) Normen Peters Statistical Office Hessen Team: Statistics Estonia - Estonia Arko Kesküla Statistics Estonia Tõnu Raitviir Statistics Estonia Anto Aasa University of Tartu Team: Central Statistics Office - Ireland Aidan Condron Central Statistics Office Sanela Jojkic Central Statistics Office Marco Grimaldi Central Statistics Office Team: Hellenic Statistical Authority - Greece Georgios Ntouros Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) Anastasia Stamatoudi Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) Emmanouil Tsardoulias Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTH) Team: Croatian Bureau of Statistics - Croatia Tomislav Jakopec J. J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Slobodan Jelić J. J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Antonija Jelinić mStart d.o.o Team: Istat - Italy Francesco Amato Istat Mauro Bruno Istat Fabrizio De Fausti Istat Team: Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia - Latvia Janis Jukams Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia Dāvis Kļaviņš Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia Jānis Muižnieks Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia Team: Statistics Netherlands (CBS) - Netherlands Benjamin Laevens Statistics Netherlands (CBS) Ralph Meijers Statistics Netherlands (CBS) Rowan Voermans Statistics Netherlands (CBS) 31 -

Facts About Tallinn 2019

FACTS 2019 ABOUT TALLINN TALLINN – Estonia’s Economic Centre 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS HISTORY: 1 TALLINN TALLINN 800 4 COMPETITIVENESS 5 BUSINESS 13 INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGY The year 2019 marks a milestone in Tallinn’s history: on June 15, the city th 17 TOURISM celebrates its 800 anniversary, commemorating its first recorded mention in the Livonian Chronicle of Henry in 1219, in which Henry of Latvia (Henricus de 23 ECONOMY Lettis) describes the battle of Lindanise Castle (today’s Toompea Hill) between 25 FOREIGN TRADE King Valdemar II of Denmark and the Estonian forces. 27 RESIDENTIAL HOUSING AND COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE As all good things come in pairs, and the city’s first mention in the chronicles is 32 POPULATION AND JOB MARKET not the only reason to celebrate: we share our great anniversary with the Danish 34 TRANSPORT state flag, the Dannebrog. According to a popular legend, the red-and-white 38 EDUCATION cross fell from the sky as a sign of support from God during the battle in Tallinn 41 ENVIRONMENT and secured a difficult victory for the Danes. 44 HEALTH CARE On 15 May 1248, Erik IV, the King of Denmark, granted Tallinn town rights under 46 SPORT the Lübeck Law, thereby joining Tallinn to the common legal space of German 50 CULTURE trading towns. 53 ADMINISTRATION AND BUDGET Tallinn, the famous Hanseatic town, received its town rights in 1248. Published by: Tallinn City Enterprise Department Tallinn is the best-preserved medieval town in Northern Europe. Design: Disainikorp Tallinn Old Town is included on the UNESCO World Heritage List. -

Situation Analysis on Evidence-Informed Health

Evidence-informed INFORMEDpolicy-making processes - MAKINGEiee-iore - poi-i proesses Evidence-informed Evidence-informed policy-making processes Health informationpolicy-making system processes e tio sst SITUATION ANALYSIS Het ior e Health research system ON EVIDENCE Health informationHealth information system system sst o 3 eser HEALTH POLICY Het r et Health research system e HealthHealth system research and system Evidence-informed Estonia policy-making context policy-making processes Het sst poi-i ot EVIPNet Europe Series, N et ot Country context Health system and Evidence-informed policy-making context Coutr policy-making processes Health system and Evidence-informed policy-making context policy-making processes Health information system Country context Country context 19/12/2017 12:16 Health information system Health research system Health information system 19/12/2017 12:16 19/12/2017 12:16 Health research system Health system and policy-makingHealth research context system Health system and policy-making context Country context Health system and policy-making context Country context Country context 2844-OMS-EURO-Cover-EvipNet-v4-20171218.indd 1-3 2844-OMS-EURO-Cover-EvipNet-v4-20171218.indd 1-3 2844-OMS-EURO-Cover-EvipNet-v4-20171218.indd 1-3 Situation analysis to improve evidence-informed health policy-making in Estonia Estonia EVIPNet Europe Series, No 3 ABSTRACT The aim of the situation analysis is to provide deeper understanding of the major factors that may facilitate or hinder the evidence-informed health policy in Estonia. It was conducted based on the WHO situation analysis manual and it found that in order to ensure research use among policy-makers in a systematic way, a knowledge translation platform could be created. -

Health Expenditure Scenarios in the New Member States Country Report on Estonia

European Network of Economic Policy Research Institutes HEALTH EXPENDITURE SCENARIOS IN THE NEW MEMBER STATES COUNTRY REPORT ON ESTONIA LIIS ROOVÄLI ENEPRI RESEARCH REPORT NO. 45 AHEAD WP9 DECEMBER 2007 ENEPRI Research Reports are designed to make the results of research projects undertaken within the framework of the European Network of Economic Policy Research Institutes (ENEPRI) publicly available. This paper was prepared as part of Work Package 9 of the AHEAD project – Ageing, Health Status and the Determinants of Health Expenditure – which has received financing from the European Commission under the 6th Research Framework Programme (contract no. SP21-CT-2003-502641). Its findings and conclusions are attributable only to the author/s and not to ENEPRI or any of its member institutions. A brief description of the AHEAD project and a list of its partner institutes can be found at the end of this report. ISBN 978-92-9079-762-3 AVAILABLE FOR FREE DOWNLOADING FROM THE ENEPRI WEBSITE (HTTP://WWW.ENEPRI.ORG) AND THE CEPS WEBSITE (WWW.CEPS.EU) © COPYRIGHT 2007, LIIS ROOVÄLI Contents Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................. i Introduction................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Health care expenditure models applied in the country.......................................................... 1 2. Synthetic description of the ILO health budget model -

Learning to Integrate: the Education of Russian-Speakers in Estonia, 1918-2000. PUB DATE 2000-12-00 NOTE 75P.; M.A

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 450 049 SO 032 561 AUTHOR Brown, Kara D. TITLE Learning To Integrate: The Education of Russian-Speakers in Estonia, 1918-2000. PUB DATE 2000-12-00 NOTE 75p.; M.A. Thesis, Indiana University. PUB TYPE Dissertations/Theses Masters Theses (042) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Comparative Education; *Educational Change; Educational History; *Educational Policy; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; *Language Role; *Minority Groups; *Official Languages; Russian; Social Integration IDENTIFIERS Educational Issues; *Estonia; Language Policy; *Russian Speaking ABSTRACT This thesis, covering the years 1918-2000, is divided into four chapters. Chapter 1 reviews the interwar history of non-Estonian education with particular emphasis on the diversity of the non-Estonian population, the legislation protecting the right of minority groups. to mother tongue instruction, and the inclusion of Estonian language and civics courses in the curricula of non-Estonian schools. Chapter 2 examines the Soviet period with an emphasis on population shifts, the destruction of all non-Russian minority education, and the lack of attention to Estonian language in the Russian school curriculum. This chapter considers the debates over language and education in Estonia during the "glastnost" period. Chapter 3 examines the post-communist reforms in language education with particular attention to varying conceptions of integration, the need for improved Estonian-language programs in Russian schools, resistance to governmental reform, and the lack of material and human resources in Russian schools. Chapter 4 argues that the changes in Estonian-language programs stem primarily from grassroots efforts and examines experimental language-programs both within and outside the formal school system. -

An Ethno-Linguistic Dimension in Transnational Activity Space Measured with Mobile Phone Data ✉ Veronika Mooses 1 , Siiri Silm 1, Tiit Tammaru 1 & Erki Saluveer 2

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00627-3 OPEN An ethno-linguistic dimension in transnational activity space measured with mobile phone data ✉ Veronika Mooses 1 , Siiri Silm 1, Tiit Tammaru 1 & Erki Saluveer 2 In addition to permanent migration, different forms of cross-border mobility were on the rise before the COVID-19 pandemic, ranging from tourism to job-related commuting. In this paper ethno-linguistic differences in cross-border mobility using the activity space framework are 1234567890():,; considered. New segregation theories emphasise that segregation in one part of the activity space (e.g. in residential neighbourhood) affects the segregation in other parts of the activity space (e.g. in workplace), and that spatial mobility between activity locations is equally important in the production and reproduction of ethnic inequalities. Until now, segregation in activity spaces has been studied by focusing on daily activities inside one country. In reality, an increasing number of people pursue their activities across different countries, so that their activity spaces extend beyond state borders, which can have important implications for the functioning of ethno-linguistic communities and the transfer of inequalities from one country to another. This study takes advantage of mobility data based on mobile phone use, and the new avenues provided for the study of ethno-linguistic differences in temporary cross-border mobility. Such data allow the study of different cross-border visitor groups—tourists, com- muters, transnationals, long-term stayers—by providing the means to measure the frequency of visits and time spent abroad, and to link together the travel of each person over several years. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2010 Dear Reader!

ANNUAL REPORT STATISTICS ESTONIA 2010 Contents Preface by Director General 3 Main events 2010 4 Fulfi lment of the statistical programme 5 New Offi cial Statistics Act 23 Preparations for transition to the euro 25 Set-up of an information system for production of statistics 26 Conference of Wiesbaden Group 27 Conference of geostatistics 28 Celebration of the World Statistics Day 29 Personnel 30 Financing 34 Publications 2010 36 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2010 Dear Reader! In Statistics Estonia the year 2010 was, in general lines, a routine one with respect to its regular and non-regular statistical actions. As usual, a number of larger and smaller development works were undertaken besides regular statistical actions. Last year, after the 2009 budget crisis, we were able to invest anew in the future. Now, we are again fully focused on further development of information systems in the fi eld of metadata, acquisition of administrative data, statistical registers, data processing applications and databases. All these works have been fi nanced from the European Union support funds. The year was also remarkable for special events and results. Ten years have passed from the previous Agricultural Census, and we collected again detailed data on agricultural holdings. We also tested the conduct of the coming 2011 Population and Housing Census. In view of a longer-term perspective, we started to work out methodology for the register-based Population and Housing Census in cooperation with the specialists in the spheres of population and administrative databases. Last year, we were more active in inviting colleagues from other countries to Estonia. -

The Estonian-Finnish Economic Cooperation

BSR Policy Briefing series 3/2019 The Estonian-Finnish economic cooperation Some recommendations for the policy-makers By Alari Purju CENTRUM Centrum Balticum Foundation reserves all the rights of this publication. BALTICUM ISSN: 2342-3153 The Estonian-Finnish economic cooperation Some recommendations for the policy-makers By Alari Purju Alari Purju is a Visiting Professor at Estonian Business School. He has been working as a Dean of the Faculty of Economics and Business Administration of Tallinn University of Technology, as an advisor to the Minister of Economic Affairs of Estonia. He has been also a consultant for the World Bank (The Commission for Growth and Development), the OECD, the EU Commission. Professor Purju holds Ph.D. from Institute of Economics of the Academy of Science of Estonia and MA in Economics from New York State University in Albany and Central European University. His scientific interest lie in comparative economic policy and public economics. Contact: [email protected] Abstract This article examines economic cooperation in different forms between Estonia and Finland. The economic growth patterns of two countries and comparison it with the EU level trends are treated. Foreign trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) are important tools of this economic cooperation and the article presents dynamics, structure and some important company level examples in these fields. The labor markets of Estonia and Finland are pooling together and the article presents trends and patterns of this phenomenon. The two countries participate also in wider EU level economic integration with supported by joint investments into large projects targeting development of infrastructure for transportation and logistics and electricity and gas. -

Sources and Data Description

OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance 2018 © OECD 2018 ANNEX B Sources and data description User guide: List of variables Variables used Page Chapter(s) Area 144 2 Business demography, births and deaths of enterprises 144 1 Employment at place of work and gross value added by industry 145 1 Foreign-born (migrants) 145 4 Gross domestic product (GDP) 146 1 Homicides 147 2 Household disposable income 148 2, 4 Households with broadband connection 149 2 Housing expenditures as a share of household disposable income 150 2 Income segregation in cities 151 4 Labour force, employment at place of residence by gender, unemployment 152 2 Labour force by educational attainment 152 2 Life expectancy at birth, total and by gender 153 2 Metropolitan population 154 4 Motor vehicle theft 155 2 Patents applications 155 1 PM2.5 particle concentration 155 2, 4 Population mobility among regions 156 3 Population, total, by age and gender 157 3 R&D expenditure and R&D personnel 158 1 Rooms per person (number of) 159 2 Subnational government expenditure, revenue, investment and debt 160 5 Voter turnout 160 2 Note on Israel: The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. 143 ANNEX B Area Country Source EU24 countries1 Eurostat: General and regional statistics, demographic statistics, population and area Australia Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), summing up SLAs Canada Statistics Canada http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census01/products/standard/popdwell/Table-CD-P.