As of January 1, 2012

COURSE SYLLABUS IGA-520 Technology, Innovation, and Sustainability Spring 2012

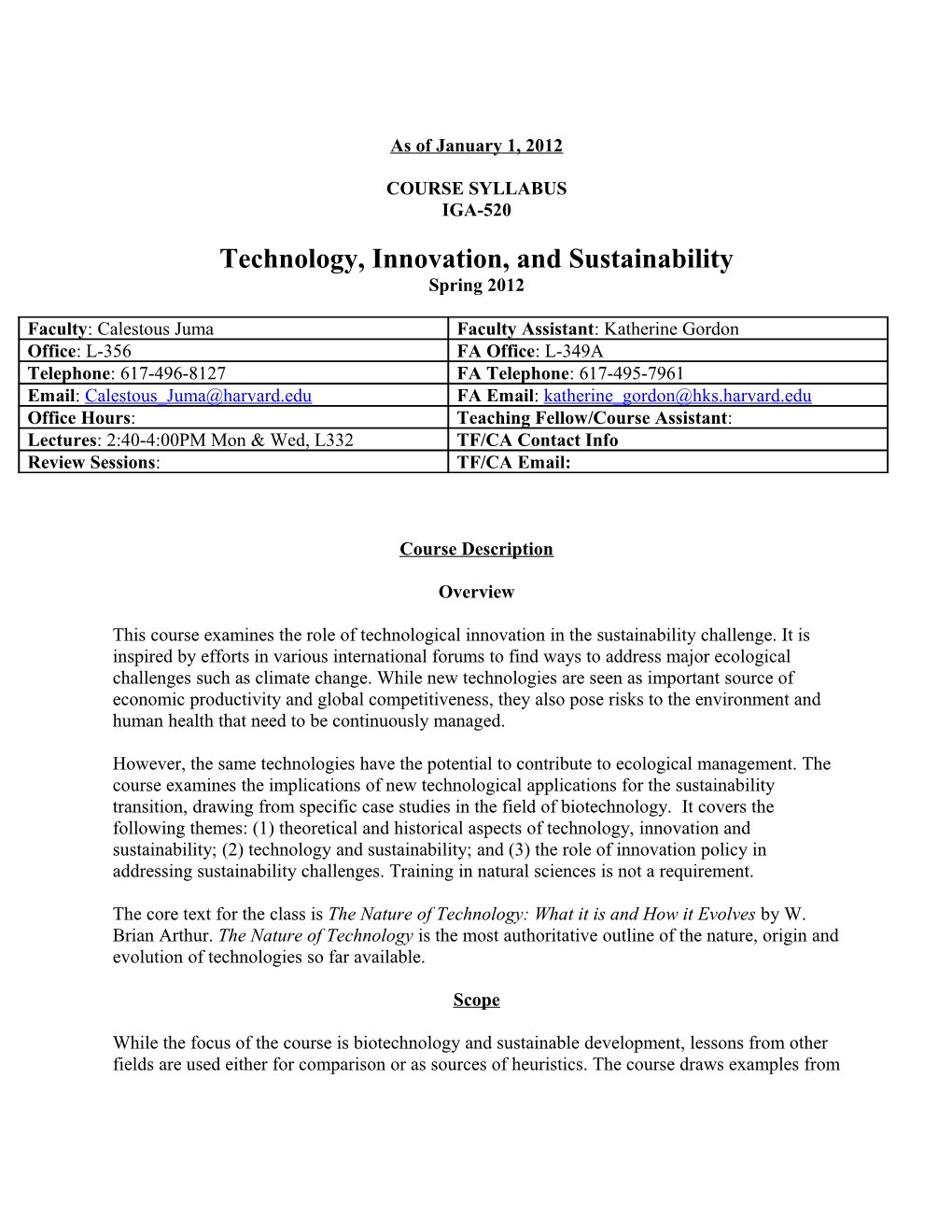

Faculty: Calestous Juma Faculty Assistant: Katherine Gordon Office: L-356 FA Office: L-349A Telephone: 617-496-8127 FA Telephone: 617-495-7961 Email: [email protected] FA Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Teaching Fellow/Course Assistant: Lectures: 2:40-4:00PM Mon & Wed, L332 TF/CA Contact Info Review Sessions: TF/CA Email:

Course Description

Overview

This course examines the role of technological innovation in the sustainability challenge. It is inspired by efforts in various international forums to find ways to address major ecological challenges such as climate change. While new technologies are seen as important source of economic productivity and global competitiveness, they also pose risks to the environment and human health that need to be continuously managed.

However, the same technologies have the potential to contribute to ecological management. The course examines the implications of new technological applications for the sustainability transition, drawing from specific case studies in the field of biotechnology. It covers the following themes: (1) theoretical and historical aspects of technology, innovation and sustainability; (2) technology and sustainability; and (3) the role of innovation policy in addressing sustainability challenges. Training in natural sciences is not a requirement.

The core text for the class is The Nature of Technology: What it is and How it Evolves by W. Brian Arthur. The Nature of Technology is the most authoritative outline of the nature, origin and evolution of technologies so far available.

Scope

While the focus of the course is biotechnology and sustainable development, lessons from other fields are used either for comparison or as sources of heuristics. The course draws examples from his historical case studies which are used to illuminate contemporary debates on the role of innovation in the sustainability transition.

Expectations

The aim of the course is to equip students with skills for identifying policy options for addressing controversial issues involving environmental management and technological innovation. This focus is a reflection of the prevalence of public controversies where technological change is both a source of ecological damage as well as solutions. For example, ozone depleting substances were a product of technological development. But so was the development of safer substitutes. A critical aspect of policy analysis is therefore outlining the interactions between technology and environment in ways that maximize human benefits while reducing the potential for ecological harm in an anticipatory way.

The course uses an interdisciplinary approach in the design and implementation of science, technology and innovation policy. In addition to building analytical competence, students will learn how to integrate knowledge from a diversity of sources and use it to identify policy options for action. The course will place emphasis on how to use public policy as a platform for problem-solving. The course is designed to accommodate students from all fields interested in the role of technological innovation in development. The course will be conducted through lectures and discussion sessions as well as occasional guest speakers. Background in the natural sciences or engineering is not a requirement.

Grading

Class participation (20%) will be evaluated on the basis of: (a) familiarity with the readings; (b) quality of contributions; (c) critical and creative approaches to the issue; and (d) respect for the views of others.

Extended outline (10%) of about 1,250 words based on the literature covered in class and identification of case material to be covered in the final paper.

Draft paper (20%) of about 2,500 covering the main contents of the paper (abstract, table of contents, introduction, analysis, conclusions and references).

Final policy analysis paper (45%) of about 5,000 words covering all the contents of the paper (abstract, table of contents, introduction, analysis, conclusions and references).

Work process, feedback and milestones

Organization of work

The course will run as a continuous project starting with early topic identification culminating in a final policy analysis paper. Class presentations, discussions and additional contacts from experts in the field will be used as continuous input into the paper. Every student will have the opportunity to get feedback at least at three stages in the course of the semester. This will be in

2 connection with topic identification, outline preparation, and draft paper. There will be no additional feedback provided after the final paper has been submitted. It is expected that students will adhere to the deadlines set for the four outputs: topic identification; extended outline; draft paper; and final paper.

Pedagogy

The pedagogic approach adopted in course builds on three key elements: problem-solving; interactive learning; and expression. To achieve this, students are expected to reach the material provided based on a set of questions that define specific problems.

Classroom activities: For most of the classes, the first 10 minutes of each class will devoted to group discussions involving sharing the knowledge from the readings and agreeing on a set of questions and comments to be presented to class for discussion. The bulk of the time will be devoted to discussion. The last five minutes of class will be devoted to a summary of the key lessons learned.

Professional contacts: The course does not involve exams but students are expected to spend part of their time reaching out to experts and practitioners in their field of interest. This is part of the learning experience but also serves as a way to develop professional contacts that might be relevant for career development of further study. Where appropriate, the class will host guest speakers as part of the professional networking process.

Feedback: The learning approach used in the course involves continuous feedback on direction and contents of the policy analysis papers. Every student will have the opportunity to get scheduled feedback at a minimum the topic identified, extended outline, and first draft. There will be additional feedback or comments provided on the final paper.

Topic identification

Early identification of topics or issues that students would like to write the policy analysis papers on is essential for the effective use of the material provided for the courses, identification of additional information and establishment of professional contacts. In this regard, students will be expected to identify the ideas they would like to work on early in the course..

Class participation and presentations

Class participation is a key part of the seminar and students will be expected to demonstrate knowledge of the readings. Students will be required to lead discussions and to participate actively in class. In addition, students will be expected to present a summary of their work to class for discussion and input.

Extended outline

Each student or groups of no more than three students will be expected to produce an outline indicating the topic he or she plans to cover in the final paper, the methods he or she will use and

3 the literature he or she will cover. The extended outline should provide a complete structure of the expected paper as well we indicative sources to be used.

Draft paper

Each student or groups of no more than three students will present their 2,500-word draft papers for comments. The draft papers should include an abstract, table of contents, introduction, analysis, conclusions and references.

The draft papers will be divided into four broad sections: (1) description of the ecological challenge that technology could help solve; (2) theoretical foundations of the role of technological innovation in environmental management; (3) case study of a technological solution to a climate change challenge; and (4) identification of policy options for action.

Final policy analysis papers

The final output from the class will be a 5,000-word policy analysis paper that identifies policy options for action regarding a particular aspect of the climate change challenge. The first paper will be a cumulative product from the entire course. It will be developed in stages which include: (1) topic identification; (2) outline of the paper; (3) draft; and (4) final paper.

Resources

In addition to the required readings, students will have opportunities to contacts development professionals associated with the Science, Technology and Globalization Project http://www.belfercenter.org/global/. Students will be supported to build professional connections with experts in their areas of interests as needed.

4 Syllabus Overview UNIT 1: TECHNOLOGY, INNOVATION, AND SOCIETY

Week One Class #1 – Mon., Jan 23: Introduction Class #2 – Wed., Jan 25: What is technology? Week Two Class #3 – Mon., Jan 30: Origins of technologies Class #4 – Wed., Feb 1: Co-evolution of technology and economy Week Three Class #5 – Mon., Feb 6: Innovation systems and sustainability transitions Class #6 – Wed., Feb 8: Technology and institutions [Topic identification due] Week Four Class #7 – Mon., Feb 13: Technological lock-in Class #8 – Wed., Feb 15: Curtailing the spread of margarine Week Five Mon., Feb. 20: PRESIDENTS’ DAY Class #9 – Wed., Feb 22: Stigmatizing alternating current UNIT 2: BIOTECHNOLOGY AND SUSTAINABILITY Week Six Class #10 – Mon., Feb 27: International diffusion of agricultural biotechnology Class #11 – Wed., Feb 29: Pest-resistant transgenic crops Week Seven Class #12 – Mon., March 5: Herbicide-tolerant transgenic crops [Outline due] Class #13 – Wed., March 7: Transgenic fish SPRINK BREAK Week Eight Class #14 – Mon., March 19: Transgenic trees Class #15 – Wed., March 21: Biofuels Week Nine Class #16 – Mon., March 26: Class presentations Class #17 – Wed., March 28: Class presentations UNIT 3: TECHNOLOGY, SUSTAINABILITY, AND PUBLIC POLICY Week Ten Class #18 – Mon., April 2: The precautionary principle Class #19 - Wed., April 4: Open discussion [First draft due] Week Eleven Class #20 – Mon., April 9: From market niches to techno-economic paradigms Class #21 – Wed., April 11: Science and technology advice Week Twelve Class #22- Mon., April 16: Science and technology diplomacy Class #23- Wed., April 18: Wrap-up Week Thirteen Class #24- Mon., April 23: Project finalization Class #25-Wed., April 25: Project finalization Tue., May 7: [Final papers due] Tue., May 15: [Grades due]

5 Class Meetings, Readings and Assignments:

UNIT 1: BACKGROUND AND CONCEPTS

Week One Class #1 – Mon., Jan 23: Introduction The introductory session covers overview of the course, expectations and introduction of the course participants.

Class #2 – Wed., Jan 25: What is technology? The term “technology” has a wide range of meaning. The aim of this session is to explore the meaning of technology as: (a) a means to meet human needs; (b) array of practices and components; and collection of devices and engineering practices available to a culture.

Read: Arthur, W.A. 2009. The Nature of Technology: What it is and How it Evolves, Free Press, New York, Chapter 2 “Combination and Structure,” pp. 27-43.

Arthur, W.A. 2009. The Nature of Technology: What it is and How it Evolves, Free Press, New York, Chapter 3 “Phenomena,” pp. 45-67.

Questions: How are technologies structured? How do natural phenomena shape the character of technology? How does technology relate to science?

Week Two Class #3 – Mon., Jan 30: Origins of technologies This session examines the origins and evolution of new technologies. It examines the mechanisms that lead to the generation of novel technologies and how they are entrenched in social and economic structure.

Read: Arthur, W.A. 2009. The Nature of Technology: What it is and How it Evolves, Free Press, New York, Chapter 6 “The Origins of Technologies,” pp. 107-130.

Arthur, W.A. 2009. The Nature of Technology: What it is and How it Evolves, Free Press, New York, Chapter 7 “Structural Deepening,” pp. 131-143.

Questions: What constitutes novelty in technology? What are the core elements of an invention? How do cumulative inventions shape the direction of the evolution of technology?

6 Class #4– Wed., Feb 1: Co-evolution of technology and economy Technology co-evolves with the economy in the same way that species co-evolve with ecosystems. This session explores the dynamics of this co-evolution and includes discussions of the implications of innovation for the future of the human race.

Read: Arthur, W.A. 2009. The Nature of Technology: What it is and How it Evolves, Free Press, New York, Chapter 10 “The Economies Evolving as its Technologies Evolve,” pp. 191- 202.

Arthur, W.A. 2009. The Nature of Technology: What it is and How it Evolves, Free Press, New York, Chapter 11 “Where Do We Stand with This Creation of Ours?,” pp. 203-216.

Questions: What is the role that technology plays in economic evolution? How does technological innovation shape the economic regeneration? How does technology affect human prospects in the age of ecological awareness?

Week Three Class #5 – Mon., Feb 6: Innovation systems and sustainability transitions The sustainability challenge represents one of the most complex contemporary policy issues. Much of the early concern over ecological degradation focused on ecological impacts of technological change. This session provides conceptual foundations for exploring the role of innovation in sustainability.

Read: Jacobsson, S. and Bergek, A. 2011. “Innovation System Analyses and Sustainability Transitions: Contributions and Suggestions for Research,” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, Vol. 1, No.1, pp. 41-57.

Smith, A. et al. 2010. “Innovation Studies and Sustainability Transitions: The Allure of the Multi-Level Perspective and its Challenges,” Research Policy, Vol. 39, No.4, pp. 435-448.

Questions: What are the essential attributes of the innovation systems analysis? What makes the innovation systems approach relevant to understanding sustainability transitions? What are the limits of applying the innovation systems approach to sustainability transitions?

Class #6– Wed., Feb 8: Technology and institutions Technological innovation is associated with adjustments in existing institutional organization arrangements. This session analyzes these co-evolutionary dynamics and lays the groundwork for understanding their policy implications.

7 Read: Nelson, R. and Nelson, K. 2002. “Technology, Institutions, and Innovation Systems,” Research Policy, Vol. 31, No. 2, pp. 265–272.

Kemp, R. and Van Lente, H. 2011. “The Dual Challenge of Sustainability Transitions,” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, Vol. 1, No.1, pp. 121-124.

Wed., Feb 8: [Topic identification due]

Questions: What are institutions and how do they differ from organizations? How do institutions hinder or facilitate technological innovation? What examples from daily life illustrate the links between technology and institutions?

Week Four Class #7 – Mon., Feb 13: Technological lock-in When society embarks on a particular technological trajectory, structures emerge that make switching to new technologies more difficult. This technological lock-in may keep more efficient of cleaner technologies out of the market. This session examines the persistence of particular technological systems in the economy.

Read: Quitzau, M.-B. 2007. “Water-flushing Toilets: Systemic Development and Path- dependent Characteristics and their Bearing on Technological Alternatives,” Technology in Society, Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 351-360.

Yarime, M. 2009. “Public Coordination for Escaping from Technological Lock-in: Its Possibilities and Limits in Replacing Diesel Vehicles with Compressed Natural Gas Vehicles in Tokyo,” Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 17, No. 14, pp. 1281-1288.

Questions: What market and non-market factors contribute to the lock-in effect? What role can the public sector play to break technological lock-in? Can you give examples of contemporary technological lock-in?

Class #8 – Wed., Feb 15: Curtailing the margarine market

The power of technological incumbency the associated political forces play an important role in shaping the pace and direction of diffusion of alternative products. This session shows how the dairy industry used laws to curtail the spread of margarine.

Read: Ball, R. and Lilly, R. 1982. “The Menace of Margarine: The Rise and Fall of a Social Problem,” Social Problems, Vol. 29, No. 5, pp. 488-498.

8 Dupré, R. 1999. “‘If It’s Yellow, It Must Be Butter’: Margarine Regulation in North America since 1886,” The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 59, No. 2, pp. 353-371.

Questions: What methods were used by the dairy industry to discriminate against margarine? What methods were used by the margarine industry to expand its market? What climate-related examples show the same discrimination against new products?

Week Five

Class #9 - Wed., Feb 22: Stigmatizing alternating current Moments of intense technological competition as associated with efforts to create images that associate the product with threats and extreme risks. This device can be done vicariously or in some cases put in practice as shown during the “war of the currents” in the early phases of electrification.

Hargadon, A. and Douglas, Y. 2001. “When Innovations Meet Institutions: Edison and the Design of the Electric Light,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 46, No. 3, pp. 476-501.

Hughes, T. 1958. “Harold P. Brown and the Executioner’s Current: An Incident in the AC-DC Controversy,” The Business History Review, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 143-165.

Questions: What strategies were used by Edison to promote the adoption of direct current? What was the origin of alternating current and how was it superior to direct current? What tactics did Edison use to slow down the adoption of alternating current?

UNIT 2: BIOTECHNOLOGY AND SUSTAINABILITY

Week Six Class #10 – Mon., Feb 27: International diffusion of agricultural biotechnology Advances in molecular biology and related fields have helped to create new products that are widely used in agriculture. This session reviews the state of the knowledge in the adoption of transgenic crops in agriculture.

Read: James, C. 2011. Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2010. International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications, Ithaca, NY, USA (Executive Summary).

Questions: What factors explain the rapid diffusion of genetically-modified (GM) crops? What are the main agronomic benefits of the GM crops? What other products exhibit similar patterns of global diffusion?

9 Class #11 – Wed., Feb 29: Pest-resistant crops The adoption of pest-resistant transgenic crops has been associated with a reduction in the use of harmful pesticides. Despite these ecological and human health benefits, there has been growing criticism of the crops. This session examines trends in the adoption of pest-resistant crops as well as the associated controversies. It outlines the key benefits as well as concerns.

Read: National Research Council. 2010. Impact of Genetically Engineered Crops on Farm Sustainability in the United States. National Academies, Washington, DC (Executive Summary and Chapter 2).

Kouser, S, and Qaim, M. 2011. “Impact of Bt Cotton on Pesticide Poisoning in Smallholder Agriculture: A Panel Data Analysis,” Ecological Economics, Vol. 70, No. 11, pp. 2105-2113.

Questions: What factors have contributed to the rapid adoption of pest-resistant transgenic crops? What are the socio-economic and health concerns and benefits of pest-resistant crops? What strategies can be adopted to address the concerns?

Week Seven Class #12 – Mon., March 5: Herbicide-tolerant crops The adoption of herbicide-tolerant transgenic crops has contributed to reductions in the use of harmful herbicides and reduced the release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere through tillage. Despite these ecological benefits, there has been growing concern over the adoption of the technology among some circles. This session examines trends in the adoption of herbicide- tolerant crops as well as the associated controversies. It outlines the key ecological benefits as well as concerns.

Read: Carpenter, J. 2011. “Impact of GM Crops on Biodiversity,” GM Crops, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 7-23.

Smyth, S.J. et al. 2011. “Environmental Impacts from Herbicide Tolerant Canola Production in Western Canada,” Agricultural Systems, Vol. 104, No. 5, pp. 403-410.

Questions: What factors contribute to the rapid adoption of herbicide-tolerant transgenic crops? What are the socio-economic sources of concern over the adoption of the crops? What strategies can be adopted to address the concerns?

Mon., March 5: [Outline due]

10 Class #13 – Wed., March 7: Transgenic fish The growing demand for fish and the decline of fisheries stocks due to overfishing has emerged as one of the most urgent themes in marine conservation. Fish engineered for fast growth and disease resistance provide a possible option for addressing environmental challenges associated with fisheries. This session examines the environmental benefits and risks as well as regulatory issues associated with transgenic fish.

Read: Le Curieux-Belfonda, O. 2009. “Factors to Consider Before Production and Commercialization of Aquatic Genetically Modified Organisms: The Case of Transgenic Salmon,” Environmental Science and Policy, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 170-189.

Van Eenennaam, A. and Muir, W. 2011. “Transgenic Salmon: A final Leap to the Grocery Shelf?” Nature Biotechnology, Vol. 29, No. 8, pp. 706– 710.http://www.pewtrusts.org/uploadedFiles/wwwpewtrustsorg/Reports/Food_and_Biote chnology/hhs_biotech_011403.pdf

Questions:

What is the current global status of fisheries? How can transgenic fish help to reduce pressure on natural fish stocks? What are the socio-economic sources of concern over transgenic fish?

SPRING BREAK

Week Eight Class #14 – Mon., March 19: Transgenic trees Biotechnology offers a wide range of techniques for forest management ranging from pest control to environmental management in the timber industry. However, applying these techniques faces challenges that are similar to those encountered in the GM food sector. This session examines the benefits and risks associated with forest biotechnology and identify policy options for action.

Read: Groover, A. 2007. “Will Genomics Guide a Greener Forest Biotech?” Trends in Plant Science, Vol. 12, No. 6, pp. 234-238. . Strauss, S.H. et al. 2009. “Strangled at Birth? Forest Biotech and the Convention on Biological Diversity,” Nature Biotechnology, Vol. 27, No. 6, pp. 519-527.

Questions: What is the global status of forest resources? What is potential role of transgenic trees in sustainable forestry? What are main sources of concern over transgenic trees?

Class #15 – Wed., March 21: Biofuels

11 The production of biofuels to replace fossil energy has emerged as one of the most elaborate efforts to make the transition toward biological processes. The aim of this session is to identify the sustainability challenges associated with the biofuels industry as review second generation advances in the technology.

Read: Hira, A. and de Oliveira, L.G. 2009. “No Substitute for Oil? How Brazil Developed its Ethanol Industry,” Energy Policy, Vol. 37, No. 6, pp. 2450-2456.

Gasparatos, A. et al. 2011. “Biofuels, “Ecosystem Services and Human Wellbeing: Putting Biofuels in the Ecosystem Services,” Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, Vol. 142, No. 3-4, pp. 111-128.

Questions: What is the potential role of biofuels in address sustainability challenges? What are the key advances in biofuels that can address sustainability challenges? What are the main sources of concern over biofuels?

Week Nine Class #16 – Mon., March 26: Class presentations

Class #17 – Wed., March 28: Class presentations

UNIT 3: TECHNOLOGY AND THE SUSTAINABILITY TRANSITION

Week Ten Class #18– Mon., April 2: The precautionary principle Concern over the unintended consequences of new technologies have resulted in the development of new concepts that demand that prior evidence of safety be provided before new products are commercialized. This session examines the history and evolution of the “precautionary principle” and its implications for the use of biotechnology for sustainability.

Read: Turvey, C. and Mojduszka, E. 2005. “The Precautionary Principle and the Law of Unintended Consequences,” Food Policy, Vol. 30, No. 2, pp. 145-161.

Brookes, G. and Barfoot, P. 2010. “Global Impact of Biotech Crops: Environmental Effects, 1996-2008,”AgBioForum, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 76-94.

Questions: What are the origins of the precautionary principle? What are the implications of the precautionary principle for innovation? What are the alternatives to the precautionary principle?

Class #19 – Wed., April 4: Regulation of transgenic crops

12 Governments around the world regulate transgenic crops either using the precautionary principle or science-based approaches that utilize the “substantial equivalence” doctrine. This session reviews available scientific evidence to determine whether transgenic crops are treated the same way as their conventional counterparts.

Read: Ricroch, A. 2011. “Evaluation of Genetically Engineered Crops Using Transcriptomic, Proteomic, and Metabolomic Profiling Techniques,” Plant Physiology, Vol. 155, pp. 1752–1761,

Chelsea, S. et al. In Press. “Assessment of the Health Impact of GM Plant Diets in Long- term and Multigenerational Animal Feeding Trials: A Literature Review,” Food and Chemical Toxicology.

Questions: What is “substantial equivalence” and how is it used in regulation? Are transgenic crops overregulated given the current state of knowledge? Should conventional crops be regulated the same way as transgenic crops?

Wed., April 4: [First draft due]

Week Eleven Class #20 – Mon., April 9: From niche markets to techno-economic paradigms shifts Deploying existing technologies and developing new ones is essential for addressing the sustainability challenge. The main policy task is moving niche markets to the creation of large-scale techno-economic paradigms. This session review policy approaches that can help foster such transitions.

Read: Nill, J. and Kemp, R. 2009. “Evolutionary Approaches for Sustainable Innovation Policies: From Niche to Paradigm?” Research Policy, Vol. 38, No. 4, pp. 668-680.

Questions: What role does advancement in technology play in the transition to a low-carbon economy? What are the key limits the transition from niche markets to techno-economic paradigms? What are the main institutional obstacles to such shifts and how can they be overcome?

Class #21 – Wed., April 11: Science and technology advice Science and technology advice is an essential input into the process of public debate over biotechnology. This session reviews the principles, procedures and institutional arrangement used to provide science and technology advice to leaders.

Read: Owens, S. 2010. “Learning Across Levels of Governance: Expert Advice and the Adoption of Carbon Dioxide Emissions Reduction Targets in the UK,” Global Environmental Change, Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 394-401.

13 Davies, K. and Wolf-Philips, J. 2006. “Scientific Citizenship and Good Governance: Implications for Biotechnology,” Trends in Biotechnology, Vol. 24, No. 2, pp. 57-61.

Questions: What mechanisms do governments use to secure expert advice on sustainability? What factors influence the success or failure of such mechanisms? What is the role of the general public in the generation and provision of expert advice?

Week Twelve Class #22 – Mon., April 16: Science and technology diplomacy International cooperation is critical to finding solutions to the sustainability challenge. But much of the diplomatic work on sustainability is carried with limited consideration of the role of technology in development in general and in international relations in particular. This session examines the extent to which technological innovation is considered as key aspect of international collaboration on sustainability.

Read: Juma, C. 2005. “The New Age of Biodiplomacy,” Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, Winter/Spring, Vo. 6, No. 1, pp. 105-114.

Juma, C. 2011. “Science Meets Farming in Africa,” Science, Vol. 334, No. 6061, p. 1323.

Questions: How does global competitiveness affect international technology cooperation? How do international trade rules affect international technology cooperation? What alternative approaches can be used to foster international technology cooperation?

Class #23 – Wed., April 18: Wrap-up

Week Thirteen Class #24 - Mon., April 23: Project finalization Class #25 – Wed., April 25: Project finalization

Mon., May 7: [Final papers due] Tue., May 15: [Grades due]

14