The Two Wise Women of Proverbs Chapter 31

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Tribute to Mother Proverbs 31

A Tribute to Mother Proverbs 31 Most of the Book of Proverbs are short statements about some truth. Yet, Proverbs 31 is the longest passage on any one subject in Proverbs. There are 22 verses on the subject of godly women. -Earlier in the book of Proverbs young men are warned against the wrong kind of woman. Solomon warns against the adulteress whose lips drip honey but who bring about death and destruction. Proverbs warns against the noisy, loud woman, the quarrelsome woman, the rebellious woman, the foolish woman. Young men looking for a mate are warned to stay away from and avoid all such women. If you were to see the last 22 verses of Proverbs 31 in the Hebrew, you would find that each one of these verses begin with each of the 22 letters in the Hebrew alphabet. Notice that 31:1 states that these words were taught to King Lemuel by his mother. -Well, who is King Lemuel? Most Bible students believe that Lemuel is the “pet name” given to Solomon by his mother, Bathsheba. You remember Bathsheba. She is the woman who was bathing in plain view of King David. She was taking a bath. That's the reason she is called Bath-sheba, you see. David lusted after her, called for her, committed adultery with her. When David found out she was with child, David had her husband killed and married her himself. You will remember that that baby died. Then she and David had a second child. His name was Solomon. The words of Proverbs are the words that he remembers his mother teaching him. -

Women Bear God's Image

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Vol. 54, No. 1, 31–49. Copyright © 2016 Andrews University Seminary Studies. WOMEN BEAR GOD’S IMAGE: CONSIDERATIONS FROM A NEGLECTED PERSPECTIVE Jo Ann Davidson Andrews University The book of Proverbs has been esteemed for centuries. Embedded in the widsom literature of the OT, it is found in all Jewish lists of the canonical books. The book is also quoted in the NT,1 as the apostles apply it to the church. Editors of the UBS list about 60 citations of direct quotations, definite allusion, and literary parallels of Proverbs in the NT, including Peter’s use of Prov 26:11 with reference to false teachers: “Of them the proverbs are true: ‘A dog returns to its vomit,’ and ‘a sow that is washed goes back to her wallowing in the mud’” (2 Pet 2:22).2 The apostles used Proverbs to instruct the church how to live godly lives: Give generously according to your ability (2 Cor 8:12, cf. Prov 3:2, 7); live humbly before God and people because “God opposes the proud, but gives grace to the humble” (Jas 4:5, 1 Pet 5:5; cf. Prov 3:34); “Fear the Lord and the king” (1 Pet 2:17, cf. Prov 24:21); “Make level paths for your feet (Heb 12:13, cf. Prov 4:26); and “If your enemy is hungry, feed him” (Rom 12:20, cf. Prov 25:21–22).3 Jesus’s acknowledgment of the wisdom of Solomon4 is further evidence of the importance of the material. Both women and men are given instruction in the thirty-one chapters of Proverbs. -

First Reading Options for the Mass of Christian Burial

First Reading Options for the Mass of Christian Burial Old Testament #1- 2 Maccabees 12:43-46S A reading from the second book of Maccabees. Judas, the ruler of Israel, then took up a collection among all his soldiers, amounting to two thousand silver drachmas, which he sent to Jerusalem to provide for an expiatory sacrifice. In doing this he acted in a very excellent and noble way, inasmuch as he had the resurrection of the dead in view; for if he were not expecting the fallen to rise again, it would have been useless and foolish to pray for them in death. But if he did this with a view to the splendid reward that awaits those who had gone to rest in godliness, it was a holy and pious thought. Thus he made atonement for the dead that they might be freed from this sin. The word of the Lord. Old Testament #2 - Job 19:23-27 A reading from the book of Job. Job answered [Bildad the Shuhite] and said: Oh, would that my words were written down! Would that they were inscribed in a record: that with an iron chisel and with lead they were cut in the rock forever! But as for me, I know that my Vindicator lives, and that he will at last stand forth upon the dust; Whom I myself shall see: my own eyes, not another's, shall behold him; and from my flesh I shall see God; my inmost being is consumed with longing. The word of the Lord. Old Testament #3 - Wisdom 3:1-9 A reading from the book of Wisdom. -

Fear God and Be Wise

FEAR GOD AND BE WISE Studies in Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Solomon The fear of the LORD is the beginning of wisdom: and the knowledge of the holy is understanding. Proverbs 9:10 Trinity Bible Church Sunday School Fall, 2006 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................. 3 Outlines .................................................................... 5 Schedule.................................................................... 6 Memory Assignment: Proverbs 1:7; 3:11-14; Ecclesiastes 1:2; 3:14; 7:13-14; 12:13-14; Song of Solomon 2:4; 8:7 ..................................... 7 Hymn: “In the Sweet Fear of Jesus”............................................... 9 Lesson 1: The Beginning of Wisdom............................................ 10 Proverbs 1 2: The Blessedness of Wisdom .......................................... 11 Proverbs 2-3 3: The Pursuit of Wisdom .............................................. 12 Proverbs 4-5 4: The Warnings of Wisdom ............................................ 13 Proverbs 6-7 5: The Call of Wisdom................................................. 14 Proverbs 8-9 6: The Proverbs of Solomon, Part 1 ....................................... 15 Proverbs 10-16 7: The Proverbs of Solomon, Part 2 ....................................... 16 Proverbs 17:1-22:16 8: The Words of the Wise and More Words of the Wise........................ 17 Proverbs 22:17-24:34 9: More Proverbs of Solomon ........................................... 18 Proverbs 25-29 10: The Words -

A Passage Containing Wisdom Principles for a Successful Marriage

Page 1 of 9 Original Research Proverbs 31:10−31: A passage containing wisdom principles for a successful marriage Author: Most commentators see Proverbs 31:10−31 as an acrostic poem about an ideal wife. True, 1,2 Robin Gallaher Branch the passage presents an exemplary woman, a paragon of industry and excellence. However, Affiliations: this article looks at this passage in a new way: it assert that the poem depicts an excellent, 1Faculty of Theology, North- successful, working marriage. The passage contains principles contained in Wisdom Literature West University, South Africa that apply to success in any relationship − especially the most intimate one of all. A careful 2Department of Bible and reading of Proverbs’ concluding poem provides a glimpse, via the specific details it shares, of Theology, Victory University, a healthy, happy, ongoing, stable marriage as observed over a span of time. United States of America Correspondence to: Robin Gallaher Branch Spreuke 31:10−31: ’n Gedeelte met wysheidsbeginsels vir ’n suksesvolle huwelik. Die meeste Skrifverklaarders beskou Spreuke 31:10−31 as ’n lettervers oor die ideale vrou. Email: [email protected] Hierdie gedeelte beeld inderdaad ’n voorbeeldige vrou uit wat ’n toonbeeld van werkywer en uitnemendheid is. Hierdie artikel kyk egter met nuwe oë na die gedeelte en voer aan dat Postal address: dit ’n voortreflike, suksesvolle en effektiewe huwelik uitbeeld. Die gedeelte bevat beginsels Department of Bible and Theology, Victory University, wat in die Wysheidsliteratuur vervat is en wat op enige suksesvolle verhouding toegepas kan 255 North Highland, word, veral op die mees intieme verhouding. ’n Noukeurige bestudering van die spesifieke Memphis, TN 38111, besonderhede van hierdie gedeelte in Spreuke bie ’n blik op ’n gesonde, gelukkige, volgehoue United States of America en stabiele huwelik soos dit oor ’n tydperk waargeneem is. -

Download Thesis

SOUTH AFRICAN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY THE PARALLEL STRUCTURE OF PROVERBS A MASTERS THESIS SUMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF BIBLICAL STUDIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER’S OF THEOLOGY BY MONROE GAULTNEY HARRISBURG, NC, 28075, USA THE PARALLEL STRUCTURE OF PROVERBS Copyright © 2005 by Monroe Gaultney All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the author. Unless otherwise stated: Scripture quotations used in this book are taken from: The HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved. 2 3 Table of Contents CHAPTER ONE ............................................................ 10 PROVERBS AND TEACHING IN ANCIENT ISRAEL......... 10 1.1 Chapter Overview .............................................. 10 1.2 Arguments For Professional Wisdom Teachers And Schools……………………………………………………………… 12 1.3 The Basic Views ……………………………………….. 14 1.4 Individual Viewpoints........................................ 14 1.5 Summary and Conclusions ................................ 18 CHAPTER TWO............................................................ 21 PROVERB AND PARALLELISM BASICS ........................ 21 2.1 Chapter Overview.............................................. 21 2:2 Defining a Proverb............................................. 21 2.3 Rhetorical Considerations: -

New Revised Standard (NRSV) New King James Version (NKJV) English

English Standard Version (ESV) Holman Christian Standard Bible (HCSB) New American Standard Bible (NASB) New International Version (NIV) New King James Version (NKJV) New Living Translation (NLT) New Revised Standard (NRSV) King James Bible (AV) Doctrines Attacked WHICH VERSION 1) Deuteronomy 23:17 - None of the daughters of Israel 1) Deuteronomy 23:17 - “No Israelite woman is to be 1) Deuteronomy 23:17 - “None of the daughters of Israel 1) Deuteronomy 23:17 - No Israelite man or woman is to 1) Deuteronomy 23:17 - “There shall be no ritual harlot of 1) Deuteronomy 23:17 - “No Israelite, whether man or 1) Deuteronomy 23:17 - None of the daughters of Israel 1) Deuteronomy 23:17 - There shall be no whore of the 1) Deuteronomy 23:17 – The Sin of Sodomy shall be a cult prostitute, and none of the sons of Israel a cult prostitute, and no Israelite man is to be a cult shall be a cult prostitute, nor shall any of the sons of become a shrine prostitute. the daughters of Israel, or a perverted one of the sons of woman, may become a temple prostitute. shall be a temple prostitute; none of the sons of Israel daughters of Israel, nor a sodomite of the sons of Israel. Do you believe that the scriptures are true? shall be a cult prostitute. prostitute Israel be a cult prostitute. Israel. shall be a temple prostitute. Do you believe that the Bible you read 2) Job 24:1 - “Why are not times of judgment kept by the 2) Job 24:1 - Why does the Almighty not reserve times 2) Job 24:1 - “Why are times not stored up by the Almighty, 2) Job 24:1 - “Why does the -

Cornerstone Biblical Commentary Vol 7: Psalms & Proverbs

CORNERSTONE BIBLICAL COMMENTARY The Book of Psalms Mark D. Futato The Book of Proverbs George M. Schwab GENERAL EDITOR Philip W. Comfort featuring the text of the NEW LIVING TRANSLATION TYNDALE HOUSE PUBLISHERS, INC. CAROL STREAM, ILLINOIS Vol7-fm.indd iii 3/4/2009 2:07:27 PM Cornerstone Biblical Commentary, Volume 7 Visit Tyndale’s exciting Web site at www.tyndale.com Psalms copyright © 2009 by Mark D. Futato. All rights reserved. Proverbs copyright © 2009 by George M. Schwab. All rights reserved. Designed by Luke Daab and Timothy R. Botts. Unless otherwise indicated, all Scripture quotations are taken from the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, copyright © 1996, 2004, 2007 by Tyndale House Foundation. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Carol Stream, Illinois 60188. All rights reserved. TYNDALE, New Living Translation, NLT, Tyndale’s quill logo, and the New Living Translation logo are registered trademarks of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cornerstone biblical commentary. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8423-3433-4 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Bible—Commentaries. I. Futato, Mark D. II. Schwab, George M. BS491.3.C67 2006 220.7´7—dc22 2005026928 Printed in the United States of America 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Vol7-fm.indd iv 3/4/2009 2:07:27 PM CONTENTS Contributors to Volume 7 vi General Editor’s Preface vii Abbreviations ix Transliteration and Numbering System xiii The Book of Psalms 1 The Book of Proverbs 451 Vol7-fm.indd v 3/4/2009 2:07:27 PM CONTRIBUTORS TO VOLUME 7 Psalms: Mark D. -

5. Appendices Proverbs 30:1 – 31:31

5. APPENDICES PROVERBS 30:1 – 31:31 85 Section Four Introduction to 30:1 - 31:31 The final two chapters consist of a number of appendices. 1The words of Agur, the son of All scholars agree that verse 1 is impossible to Yakeh, of Massa; the utterance translate with any degree of confidence. McKane of the man. There is no God, spends four pages on it (pages 644-647), and I am there is no God and I am ex- following his translation of verses 1-4. hausted; ‘Massa’ may be the name of a north Arabian tribe 2for I am more beast than a (see Genesis 25:14; 1Chronicles 1:30). man, and human discernment McKane writes (pages 646-647): is not given to me. 3I have not learned wisdom, nor do I have Agur’s tone in vv. 2f. appears to be ironical. knowledge of the Holy One. With a mock ruefulness he observes that others 4 seem to know all about God and have him com- Who has ascended to heaven pletely in their grasp, whereas he, poor fellow, and come down again? Who is apparently sub-human, since for him God is has held the wind in his hands? shrouded in mystery. He has never been able to Who has wrapped the waters penetrate this domain of knowledge in which in a cloak? Who has estab- others seem to move with great familiarity and lished all the ends of the earth? assurance. If this is what is indicated by vv. 2f., What is his name, and his son’s it is compatible with the weary or despairing name, if indeed you know? searcher after God who has been created by the reconstruction of v. -

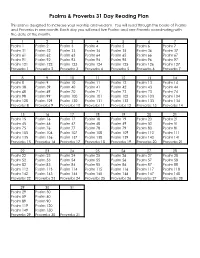

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

(#208) the Proverbs of Solomon Proverbs 31:1-3- Listen to Your Mama About Women

Studies in the Book of Proverbs by John T Polk II For The Fellowship Room (#208) The Proverbs of Solomon Proverbs 31:1-3- Listen to Your Mama About Women Since God Created humans, only God can provide specific understanding of human behavior. God gave Solomon Divine Wisdom (1 Kings Chapters 3 and 10) to explain what and why behavior is as it is, and Proverbs 30-31 were added and preserved by the Holy Spirit. New Testament passages may help see the continuation of Wisdom offered through Jesus Christ. Proverbs 31:1-3: The words of King Lemuel, the utterance which his mother taught him: 2 What, my son? And what, son of my womb? And what, son of my vows? 3 Do not give your strength to women, nor your ways to that which destroys kings. Verse 1: These have been the Proverbs of Solomon: for his son (Chapters 1-9); for his people (Chapters 10-24); for his legacy (Chapters 25-29); for his influence (Chapters 30-31). The Book of Proverbs began with a father instructing his son, and ends in this last chapter with the mother’s wise words, or “hear the instruction of your father, and do not forsake the law of your mother” (Proverbs 1:8). Verse 2: Almost asking: “What can I say for the best benefit for my son, my flesh and blood?” “Son of my womb” refers to the closeness of the mother-son bond, for she was his home before he was born. “Son of my vows” can refer to the legitimate son born after marriage vows of his parents (Malachi 2:14), or to parental commitment to raise the child “in the training and admonition of the Lord” (Ephesians 6:4). -

Proverbs 30:18-19 in the Light of Ancient Mesopotamian Cuneiform Texts

SEFARAD (Sef ) Vol. 69:2, julio-diciembre 2009 págs. 263-279 ISSN 0037-0894 Proverbs 30:18-19 in the Light of Ancient Mesopotamian Cuneiform Texts Barbara Böck * ILC – CSIC, Madrid The meaning of Proverbs 30:18-19 has long been disputed. Most scholars interpret the Biblical couplets textually on stylistic features only; an explanation of the contextual association between the four motifs mentioned (eagle, serpent, boat, man and woman) has not yet been undertaken. The present paper aims at shedding light on the motivation for this association, taking into consideration ancient Near Eastern cuneiform compositions for the first time. It is further suggested that Proverbs 30:18-19 derived originally from a riddle that had its setting in a wedding ceremony. KEYWORDS: Biblical Proverbs; Metaphors of Procreation; Ancient Near Eastern Background; Riddles. PROVERBIOS 30:18-19 A LA LUZ DE LOS ANTIGUOS TEXTOS MESOPOTÁMICOS CUNEIFORMES.— El significado deProverbios 30:18-19 sigue desafiando la exégesis de los biblistas. La mayoría de los comentaristas interpretan los versos bíblicos textualmente, ciñéndose al análisis de las figuras de estilo. Sin embargo, todavía no se ha dado ninguna explicación a la asociación contextual entre los cuatro motivos del proverbio (águila, serpiente, barco, hombre y mujer). Por primera vez, este artículo estudia composiciones de la literatura cuneiforme que ofrecen un telón de fondo para interpretar el sentido de los distintos elementos y del conjunto del proverbio bíblico. Según esta nueva lectura, Proverbios 30:18-19 describiría una adivinanza propuesta durante una ceremonia matrimonial. PALABRAS CLAVE: Proverbios bíblicos; metáforas de procreación; antigua Mesopotamia; adivinanzas. More than a century of research has provided a scattering of potential bor- rowings from Ancient Mesopotamia into Israelite literature.