Performance Analysis and Tuning of Parallel Programs: Resources and Tools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IBM Power® Systems for SAS® Empowers Advanced Analytics Harry Seifert, Laurent Montaron, IBM Corporation

Paper 4695-2020 IBM Power® Systems for SAS® Empowers Advanced Analytics Harry Seifert, Laurent Montaron, IBM Corporation ABSTRACT For over 40+ years of partnership between IBM and SAS®, clients have been benefiting from the added value brought by IBM’s infrastructure platforms to deploy SAS analytics, and now SAS Viya’s evolution of modern analytics. IBM Power® Systems and IBM Storage empower SAS environments with infrastructure that does not make tradeoffs among performance, cost, and reliability. The unified solution stack, comprising server, storage, and services, reduces the compute time, controls costs, and maximizes resilience of SAS environment with ultra-high bandwidth and highest availability. INTRODUCTION We will explore how to deploy SAS on IBM Power Systems platforms and unleash the full potential of the infrastructure, to reduce deployment risk, maximize flexibility and accelerate insights. We will start by reviewing IBM and SAS’s technology relationship and the current state of SAS products on IBM Power Systems. Then we will look at some of the infrastructure options to deploy SAS 9.4 on IBM Power Systems and IBM Storage, while maximizing resiliency & throughput by leveraging best practices. Next, we will look at SAS Viya, which introduces changes to the underlying infrastructure requirements while remaining able to be deployed alongside a traditional SAS 9.4 operation. We’ll explore the various deployment modes available. Finally, we’ll look at tuning practices and reference materials available for a deeper dive in deploying SAS on IBM platforms. SAS: 40 YEARS OF PARTNERSHIP WITH IBM IBM and SAS have been partners since the founding of SAS. -

POWER® Processor-Based Systems

IBM® Power® Systems RAS Introduction to IBM® Power® Reliability, Availability, and Serviceability for POWER9® processor-based systems using IBM PowerVM™ With Updates covering the latest 4+ Socket Power10 processor-based systems IBM Systems Group Daniel Henderson, Irving Baysah Trademarks, Copyrights, Notices and Acknowledgements Trademarks IBM, the IBM logo, and ibm.com are trademarks or registered trademarks of International Business Machines Corporation in the United States, other countries, or both. These and other IBM trademarked terms are marked on their first occurrence in this information with the appropriate symbol (® or ™), indicating US registered or common law trademarks owned by IBM at the time this information was published. Such trademarks may also be registered or common law trademarks in other countries. A current list of IBM trademarks is available on the Web at http://www.ibm.com/legal/copytrade.shtml The following terms are trademarks of the International Business Machines Corporation in the United States, other countries, or both: Active AIX® POWER® POWER Power Power Systems Memory™ Hypervisor™ Systems™ Software™ Power® POWER POWER7 POWER8™ POWER® PowerLinux™ 7® +™ POWER® PowerHA® POWER6 ® PowerVM System System PowerVC™ POWER Power Architecture™ ® x® z® Hypervisor™ Additional Trademarks may be identified in the body of this document. Other company, product, or service names may be trademarks or service marks of others. Notices The last page of this document contains copyright information, important notices, and other information. Acknowledgements While this whitepaper has two principal authors/editors it is the culmination of the work of a number of different subject matter experts within IBM who contributed ideas, detailed technical information, and the occasional photograph and section of description. -

IBM AIX Version 6.1 Differences Guide

Front cover IBM AIX Version 6.1 Differences Guide AIX - The industrial strength UNIX operating system AIX Version 6.1 enhancements explained An expert’s guide to the new release Roman Aleksic Ismael "Numi" Castillo Rosa Fernandez Armin Röll Nobuhiko Watanabe ibm.com/redbooks International Technical Support Organization IBM AIX Version 6.1 Differences Guide March 2008 SG24-7559-00 Note: Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page xvii. First Edition (March 2008) This edition applies to AIX Version 6.1, program number 5765-G62. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 2007, 2008. All rights reserved. Note to U.S. Government Users Restricted Rights -- Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents Figures . xi Tables . xiii Notices . xvii Trademarks . xviii Preface . xix The team that wrote this book . xix Become a published author . xxi Comments welcome. xxi Chapter 1. Application development and system debug. 1 1.1 Transport independent RPC library. 2 1.2 AIX tracing facilities review . 3 1.3 POSIX threads tracing. 5 1.3.1 POSIX tracing overview . 6 1.3.2 Trace event definition . 8 1.3.3 Trace stream definition . 13 1.3.4 AIX implementation overview . 20 1.4 ProbeVue . 21 1.4.1 ProbeVue terminology. 23 1.4.2 Vue programming language . 24 1.4.3 The probevue command . 25 1.4.4 The probevctrl command . 25 1.4.5 Vue: an overview. 25 1.4.6 ProbeVue dynamic tracing example . 31 Chapter 2. File systems and storage. 35 2.1 Disabling JFS2 logging . -

Raiffeisenbank Speeds Data Warehouse, Cuts Costs with Red Hat Enterprise Linux

CUSTOMER CASE STUDY RAIFFEISENBANK SPEEDS DATA WAREHOUSE, CUTS COSTS WITH RED HAT ENTERPRISE LINUX Raiffeisenbank, a banking institution that provides a wide range of services to private and corporate clients in the Czech Republic, needed to replace the aging hardware and IBM AIX operating system that supported its data warehouse. By migrating to Red Hat Enterprise Linux running on cost-effective Hitachi servers with Intel processors, the bank has tripled system performance speed and maintained stability — while cutting total cost SOFTWARE AND of ownership (TCO) by 50%. SERVICES Red Hat® Enterprise Linux® HARDWARE Hitachi Unified Compute Platform for Oracle Database Hitachi Compute Blade 2500 Prague, Czech Republic FINANCIAL SERVICES (CB 2500) Hitachi Virtual Storage HEADQUARTERS 3,000 EMPLOYEES Platform G600 (VSP G600) 120 BRANCHES PARTNER “There are many benefits to using Red Hat MHM computer a.s. and Oracle solutions together, and also BENEFITS from moving from IBM to Intel. We feel • Achieved three times faster a combination of Red Hat and Oracle on system performance an Intel platform is a preferred solution • Anticipates 50% decrease for any company.” in total cost of ownership over five years JIŘÍ KOUTNÍK HEAD OF SYSTEM ADMINISTRATION, • Gained greater flexibility by RAIFFEISENBANK eliminating vendor lock-in facebook.com/redhatinc @redhatnews linkedin.com/company/red-hat redhat.com AGING UNIX SYSTEM TOO SLOW FOR MODERN BUSINESS Raiffeisenbank a.s. provides a wide range of banking services to private and corporate clients in the Czech Republic at more than 120 branches and business client centers. The bank offers corpo- rate and personal finance products and services related to savings, insurance, and leasing, including specialized mortgage centers and business advisors. -

GSI Local Guide

UNIX Primer GSI Local Guide GSI Computing Center Version 2.0 This is draft version !!! Preface: More than one year ago, we published our ®rst version of the Unix primer, which has been used in the meantime by many people at GSI and even in the outside HEP community. Nowadays, as more and more physicists have access to a Unix computer either via a X-terminal or use their own workstation, and as the installed computing power has increased by a large factor, we have revised the ®rst version of our Unix primer. We tried to re¯ect the changes in the installedhardware, like the installationof the 11 machine AIX cluster, and the installationof new software products, as the batch system for job submission, new backup and restore products and the graphics system IDL. Almost all chapters have been revised, and some have undergone substantial changes like the introduction, the section about experimental data and tape handling and the chapter about the editors, where more editors are described in detail. Although many topics are still missing or could be improved, we decided to publishthe second edition of the Unix primer now in order to give a guide to the rapidly increasing Unix user community at GSI. As for the ®rst edition, many people again have contributed to this document: Wolfgang Ahner, Eliete Bertulani, Michael Dahlinger, Matthias Feyerabend, Ingo Giese, Horst GÈoringer, Eva Hocks, Peter Malzacher, Udo Meyer, Kerstin Schiebel, Kay Winkler and Heiko Weber. Preface for Version 1.0: In early summer 1991 the GSI Computing Center started a Unix Pilot Project investigating the hardware and software possibilities of centrally operated unix workstation systems. -

Programming the Cell Broadband Engine Examples and Best Practices

Front cover Draft Document for Review February 15, 2008 4:59 pm SG24-7575-00 Programming the Cell Broadband Engine Examples and Best Practices Practical code development and porting examples included Make the most of SDK 3.0 debug and performance tools Understand and apply different programming models and strategies Abraham Arevalo Ricardo M. Matinata Maharaja Pandian Eitan Peri Kurtis Ruby Francois Thomas Chris Almond ibm.com/redbooks Draft Document for Review February 15, 2008 4:59 pm 7575edno.fm International Technical Support Organization Programming the Cell Broadband Engine: Examples and Best Practices December 2007 SG24-7575-00 7575edno.fm Draft Document for Review February 15, 2008 4:59 pm Note: Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page xvii. First Edition (December 2007) This edition applies to Version 3.0 of the IBM Cell Broadband Engine SDK, and the IBM BladeCenter QS-21 platform. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 2007. All rights reserved. Note to U.S. Government Users Restricted Rights -- Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Draft Document for Review February 15, 2008 4:59 pm 7575TOC.fm Contents Preface . xi The team that wrote this book . xi Acknowledgements . xiii Become a published author . xiv Comments welcome. xv Notices . xvii Trademarks . xviii Part 1. Introduction to the Cell Broadband Engine . 1 Chapter 1. Cell Broadband Engine Overview . 3 1.1 Motivation . 4 1.2 Scaling the three performance-limiting walls. 6 1.2.1 Scaling the power-limitation wall . 6 1.2.2 Scaling the memory-limitation wall . -

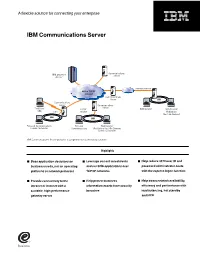

IBM Communications Server

A flexible solution for connecting your enterprise IBM Communications Server ^ Communications IBM Server zSeriesTM Internet/extranet SNA or TCP/IP intranet Communications Server LAN Communications Server Communications Server Traditional TCP/IP Web browser Web browser SNA SNA intranet WebSphere Host On-Demand LAN LAN Personal Communications Personal Web browser Screen Customizer Communications WebSphere Host On-Demand Screen Customizer IBM Communications Server provides a comprehensive connectivity solution. Highlights ■ Base application decisions on ■ Leverage current investments ■ Help reduce 3270 user ID and business needs, not on operating and run SNA applications over password administrator costs platforms or network protocols TCP/IP networks with the express logon function ■ Provide connectivity to the ■ Help protect business ■ Help boost network availability, intranet or Internet with a information assets from security efficiency and performance with scalable, high-performance breaches load balancing, hot standby gateway server and HPR As your business needs grow, place, while making the transition at applications over existing SNA chances are, so will your network. your own pace. IBM Communications networks without adding a separate Explosive growth and constant change Server can connect your employees, TCP/IP network. And you can extend in the information management and customers and trading partners to SNA applications to TCP/IP users delivery arena call for versatile the information and applications they without the addition of a separate technologies to meet your company’s need, independent of the underlying SNA network. growing needs. IBM Communications network. Designed to meet your Server meets the challenge—offering company’s growing e-business needs, Reliability and flexibility a comprehensive package of IBM Communications Server provides IBM Communications Server also enterprise networking solutions to fast, efficient ways to extend data to works as a Telnet server, providing effectively connect your employees, Web users. -

IBM AIX Dynamic System Optimizer Version 1.1

IBM AIX Dynamic System Optimizer Version 1.1 IBM AIX Dynamic System Optimizer IBM Note Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page 11 . This edition applies to IBM AIX Dynamic System Optimizer Version 1.1 and to all subsequent releases and modifications until otherwise indicated in new editions. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 2012, 2017. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents About this document..............................................................................................v IBM AIX Dynamic System Optimizer.......................................................................1 What's new...................................................................................................................................................1 Concepts.......................................................................................................................................................1 Active System Optimizer........................................................................................................................ 1 IBM AIX Dynamic System Optimizer offering........................................................................................2 Workload requirements..........................................................................................................................3 Environment variables............................................................................................................................4 -

IBM SPSS Statistics V26 Delivers Powerful New Statistics, Procedure

IBM United States Software Announcement 219-193, dated April 9, 2019 IBM SPSS Statistics V26 delivers powerful new statistics, procedure and scripting advancements, and production facility enhancements; IBM ILOG CPLEX Optimization Studio V12.9 includes new license option Table of contents 1 Overview 5 Technical information 2 Key requirements 6 Ordering information 2 Planned availability date 61 Terms and conditions 2 Description 61 Prices 4 Program number 62 Order now 5 Publications At a glance IBM(R) SPSS(R) Statistics software is used by a variety of clients to solve industry- specific business and research issues to drive quality decision-making. Advanced statistical procedures and visualization can provide a robust, user friendly and an integrated platform to understand client data and to solve complex business and research problems. Highlights in version 26 include: • Ability to analyze data with powerful new statistics • Advancements to existing procedures and scripting commands – Enhancements to Bayesian statistics – Reliability analysis improvements – Improved scripting commands • Production facility enhancements IBM ILOG(R) CPLEX(R) Optimization Studio ILOG CPLEX Optimization Studio V12.9 includes a new monthly Project Edition license, which provides the organization entitlement to both development and deployment editions. This allows the organization the opportunity to determine which option is the better solution before making a decision regarding a perpetual license. Overview SPSS Statistics V26 can help: • Analyze data with powerful new statistics. – Obtain a more comprehensive analysis of the relationship between variables by using Quantile regression. – Assess the accuracy of model predictions visually by plotting a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. This is one of the most important evaluation metrics for checking any classification model's performance. -

Comparing Solaris to Redhat Enterprise And

THESE ARE TRYING TIMES IN SOLARIS- land. The Oracle purchase of Sun has caused PETER BAER GALVIN many changes both within and outside of Sun. These changes have caused some soul- Pete’s all things Sun: searching among the Solaris faithful. Should comparing Solaris to a system administrator with strong Solaris skills stay the course, or are there other RedHat Enterprise and operating systems worth learning? The AIX decision criteria and results will be different for each system administrator, but in this Peter Baer Galvin is the chief technologist for Corporate Technologies, a premier systems column I hope to provide a little input to integrator and VAR (www.cptech.com). Before that, Peter was the systems manager help those going down that path. for Brown University’s Computer Science Department. He has written articles and columns for many publications and is co- Based on a subjective view of the industry, I opine author of the Operating Systems Concepts that, apart from Solaris, there are only three and Applied Operating Systems Concepts worthy contenders: Red Hat Enterprise Linux (and textbooks. As a consultant and trainer, Peter teaches tutorials and gives talks on security its identical twins, such as Oracle Unbreakable and system administration worldwide. Peter Linux), AIX, and Windows Server. In this column blogs at http://www.galvin.info and twitters I discuss why those are the only choices, and as “PeterGalvin.” start comparing the UNIX variants. The next [email protected] column will contain a detailed comparison of the virtualization features of the contenders, as that is a full topic unto itself. -

IBM Power9oracle11g12c April 10 2018 Final.Pdf

Oracle Database 11g and 12c on IBM Power Systems S924, S922 and S914 with POWER9 processors Tips and considerations ........ Ravisankar Shanmugam Moshe Reder, Wayne Martin IBM Oracle International Competency Center April 2018 © Copyright IBM Corporation, 2018. All Rights Reserved. All trademarks or registered trademarks mentioned herein are the property of their respective holders Table of contents Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 New IBM Power Systems product line .................................................................................... 2 IBM AIX and Linux support ...................................................................................................................... 3 Recommended code levels ..................................................................................................................... 4 Service strategy ................................................................................................................. 4 C and C++ compilers ............................................................................................................................... 4 Oracle Database and IBM Power Systems.............................................................................. 5 Current certifications ............................................................................................................................... -

IBM Power Systems for Oracle E-Business Suite

IBM Power Systems for Oracle E-Business Suite Powerful, dynamic systems with POWER8 processors keep you ahead of the latest technology trends Designed and built for your business Built with innovation that puts data to work critical Oracle E-Business Suite It’s no secret that dynamic technology changes are rapidly remaking how deployments organizations do business. The growing torrent of data from both within and outside your organization, from mobile employees and from customers and Data-centric design and optimization prospects, presents an unprecedented opportunity to gain valuable insights and brings faster insight to the point of apply these insights at the best point of impact to improve your business results. impact Making the transition to advanced capabilities requires an integrated infrastructure Improved IT economics efficiently that supports your key IT initiatives, and business critical Oracle E-Business Suite deliver business services with a deployments. Our investments to bring optimized solutions in the areas of big data, scalable, open cloud analytics, cloud, and mobile access are designed to simplify and accelerate your Joint IBM and Oracle testing, planning, journey to address today’s market opportunities. and support deliver a robust enterprise- class computing platform for Oracle The newest generation of IBM® Power Systems™, with POWER8™ technology, E-Business Suite is the first family of systems built with innovations that transform the power of big data and analytics, mobile, and cloud into competitive advantages in ways never before possible. Optimized for the rigorous demands of enterprise computing IBM understands that applications and business processes have differing demands and that one size does not fit all.