SUPPLEMENTARY STATEMENT OF N J FRANGOS (“FRANGOS”) TO THE MINISTERIAL ENQUIRY INTO THE AFFAIRS OF CORPCAPITAL – ANALYSIS OF, AND RESPONSES TO, THE STATEMENTS OF: JADE HAMBURGER (“HAMBURGER”), KEVIN JOSELOWITZ (“JOSELOWITZ”) AND MARK MATISSON (“MATISSON”)

1. What is Hamburger saying?

1.1 Responsibility for Cytech

1.1.1 I have been intimately involved in Corpcapital’s investment in Cytech since inception. (Executive Summary, point 2)

1.1.2 I was responsible for all indicative valuations. (Executive Summary, point 3)

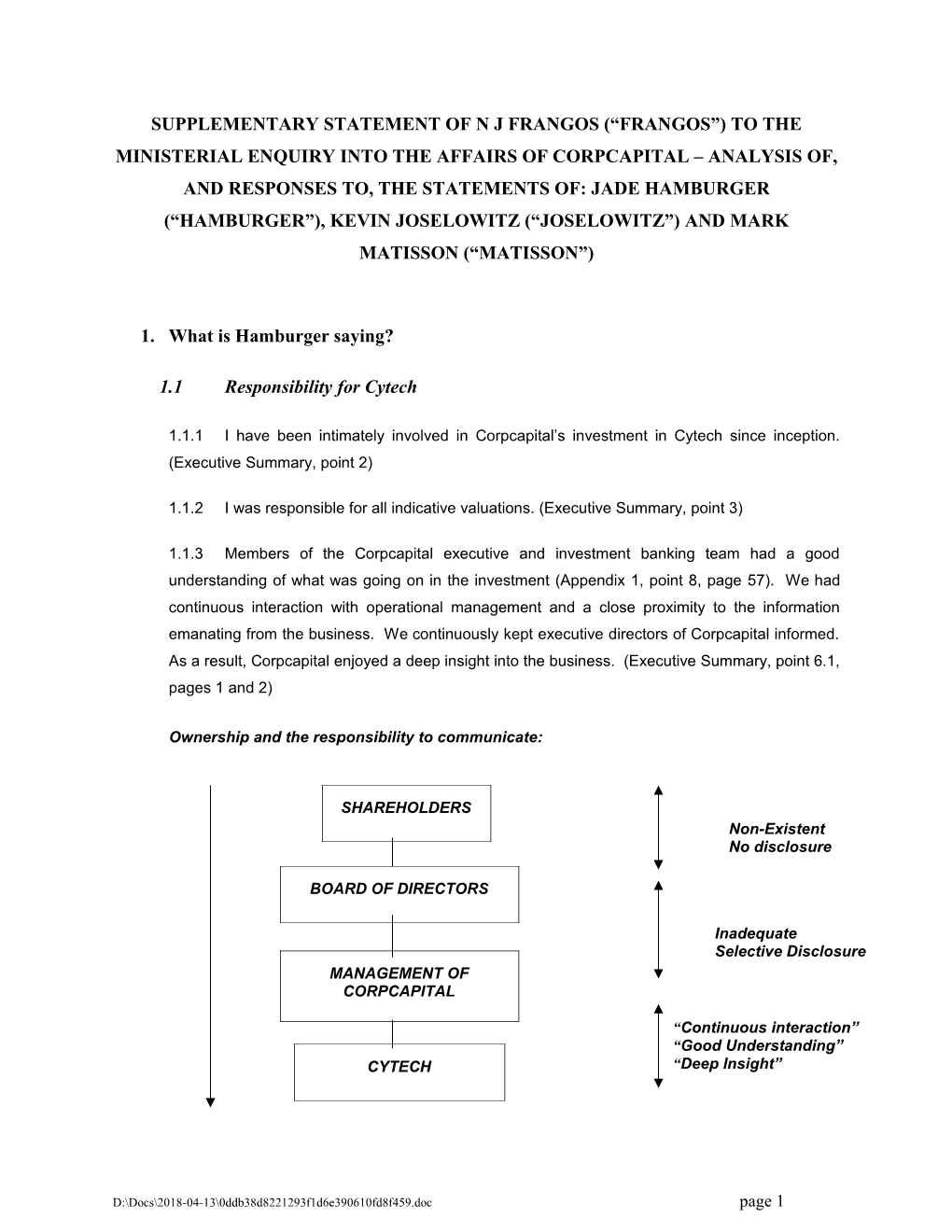

1.1.3 Members of the Corpcapital executive and investment banking team had a good understanding of what was going on in the investment (Appendix 1, point 8, page 57). We had continuous interaction with operational management and a close proximity to the information emanating from the business. We continuously kept executive directors of Corpcapital informed. As a result, Corpcapital enjoyed a deep insight into the business. (Executive Summary, point 6.1, pages 1 and 2)

Ownership and the responsibility to communicate:

SHAREHOLDERS Non-Existent No disclosure

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Inadequate Selective Disclosure MANAGEMENT OF CORPCAPITAL

“Continuous interaction” “Good Understanding” CYTECH “Deep Insight”

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 1 Since shareholders own the company, they have a right to expect that their elected representatives, the Board of Directors, will keep them informed on material matters. This can only happen if the CEO and his team keep the Board fully informed. The CEO bears the responsibility of accurately reporting the condition of the company to the Directors. The CEO has greater knowledge and expertise in company matters than the Board. It is the CEO who also determines what information directors receive. In most instances directors understand the company through the CEO’s eyes. This was the case at Corpcapital.

Cytech was a material investment for Old Corpcapital and Corpcapital. Amongst the management of Corpcapital there was a full awareness of everything to do with Cytech. Hamburger is at pains to explain the extent of his communication with management and his continuous direct access to the Group CEO, Jeff Liebesman (“Liebesman”). Thereafter there was a breakdown in communication between the management of Corpcapital and the Board of Directors. Management failed to communicate adequately with the Board on fundamental matters relating to Cytech. As a result, there was no communication of significance by the Board to the shareholders. By failing to communicate the facts, therefore, management withheld material information from the investing public about the true situation at Corpcapital.

In June 2002, following an investigation, I brought matters of concern relating to Cytech to the attention of the Board of Directors of Corpcapital. The directors had a responsibility to investigate the matter individually and to apply their minds independently. This did not happen.

1.2 Selection of DCF method of valuation

1.2.1 Fair value was capable of being measured reliably, and therefore the DCF method of valuation was appropriate. (Executive Summary, point 7, page 3)

1.2.1.1 Cytech had a track record and concrete business plans which facilitated reasonable projections. (Executive Summary, point 7, page 3)

Apart from the first six months in 1999, sales and profit forecasts were never achieved and the results were highly volatile. Hamburger paints a picture of total involvement in all of the detail of Cytech. In spite of this they were never able to forecast to any acceptable tolerance level in respect of the deviation between actuals and forecast. The following table illustrates the high error rate experienced by management in achieving their own PBT forecasts for the purposes of valuation. All forecasts are in US$m.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 2 Forecast 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 A 4.7 11.1 12.1 B 8.3 11.6 14.0 C 6.9 11.9 13.5 D - 6.7 9.6 12.4 E 2.4 Act 4.5 5.8 6.6 % Increase +87% +29% +14% Actual 2.7 2.4

Forecast A was the projections used to determine a value at 31 August 2000.

Forecast B was the projections used to determine a value at 28 February 2001.

Forecast C was the projections used to determine a value at 31 August 2001.

Forecast D was the projections used to determine a value at 28 February 2002.

Forecast E was the estimates given by Corpcapital to Peter Goldhawk (“Goldhawk”) for valuation at 31 August 2002.

In every case the actual was significantly less than the last estimate. The 2002 column shows that the actual PBT achieved was 35% of the last forecast (Forecast C), 21% of Forecast B and 22% of Forecast A. The PBT actuals for 2001 and 2002 are shown prior to the adjustments made by Corpcapital. In 2001 these adjustments amounted to $1.9m. The actual PBT for the twelve months to 31 August 2000 were $1.8m. The table illustrates not only the unpredictability of results, but also the aggressive projections made by Corpcapital.

1.2.1.2 In relation to each valuation, I was satisfied that Corpcapital’s investment in Cytech was capable of being measured reliably, and constituted a reasonable estimate of the valuation of the investment. (Statement, point 84, page 16)

Management was an interested party, a fact known to the auditors. It was therefore finally up to the external auditors, Fisher Hoffman Sithole (“FHS”), and the Audit Committee to determine whether or not Corpcapital’s investment in Cytech could be measured reliably. If there was any doubt, both the auditors and the Audit Committee should have referred the matter to external expert opinion.

1.2.1.3 Netainment was no longer a start-up company at the August 2000 valuation. It had a track record of increasing turnover and cash profits. (Statement, point 127, page 27)

The statement does not survive scrutiny in the context of accepted organization life cycle theory. The South African experts in this area are Professor Andy Andrews and Professor Nick Binedell of GBS. Every business school in the world would acknowledge the close relationship between stage of life cycle and volatility. The

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 3 online casino commenced operations in December 1998. It had been in operation for only eight months prior to the commencement of the seminal 2000 financial year. This would classify it still as a start up, or infant organisation during 2000 and thereafter as an early stage company. The degree of precision in valuations varies widely across investments. The stage that a company is in of its life cycle correlates closely to the volatility of its results and the ability to predict its performance.

Courtship Infancy Go-Go Adolescence Prime Stable Mature Decline

1997/1998 Development of Start Dec concept 1998 1999 2000 2001

Divorce

Founder’s Trap 2002 2003 Infant Mortality

Degree of Predictiveness Low Low Low Medium High High MH Low

Model developed by Dr. Ichak Adizes of the Adizes Institute, USA.

Cytech entered its infancy in December 1998. It appears to be currently in infant mortality, and its survival is in serious doubt. “Early stage” is classified as infancy and Go-Go. The survival rate in the US of infant companies is 1 in 10, and 3 in 10 in the Go-Go stage. The best companies take many years to go through each stage. Each stage has its own unique challenges. The benchmark that companies aspire to is to become a “Prime” company. The characteristics of a prime company are:

It is producing predictable results in the short, medium and long-term, and is able to forecast reliably. It has drive and is knowledgeable about its products, markets, competition and how to respond to changes in the external environment, It has a strong administrative set up, with all of the necessary checks and balances. Attention to detail is excellent and it has systematized its processes, It has retained a strong creative ability, and is able to reliably assess risk, It has institutionalized the human factor. Good succession plans exist, and the company is seen in the market as a good employer.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 4 The assertion by Hamburger that Cytech had exited early stage and that it was stable and predictable, is an incorrect assessment. Cytech was a two-man virtual company in its infancy throughout all periods.

Some South African examples illustrate the point:

INFANCY AND GO-GO Idion, Softline, Frontrange, Cadiz, Redefine INFANT MORTALITY AND FOUNDERS TRAP Didata and most IT companies, A2 banks including Global Technology, AST, AMB, Brait, MGX ADOLESCENCE Peregrine, Adcorp, Discovery, African Bank PRIME Bidvest, Standard Bank, Tiger Brands, Massmart, Alexander Forbes, Anglo Platinum STABLE Absa, Liberty, Remgro, RMG, Wooltru, SAB, Pick ‘n Pay MATURE Old Mutual, Sanlam, Barlows, Nampak DECLINE Sage, Mutual & Federal, Seardel, Nedcor

As can be seen, size does not define stage of life cycle, only the condition and characteristics do this. Organisation life cycle theory has been around for a long time. It is not surprising that Cytech, as an infant organisation, did not meet its sales forecasts by a wide margin. There is inherently a high level of volatility in infant organisations, and more so when they operate in emerging industries. For these reasons, Cytech could never be “measured reliably”.

Early Stage Investing

Providers of capital follow defined benchmarks in respect of relating risk level to life cycle and how to position themselves in niches. Each niche has its own characteristics.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 5 High Founder, friends, and family Business angels Venture Level of capitalists Investment Non-financial Risk Assumed corporations by Investor Equity markets

Commercial banks Low

Seed Start-up Early growth Established

Stage of Development of Entrepreneurial Firm

The biggest disadvantages of early stage investing involve high risk and high mortality rates. In the United States the type of investments matches the stage of the life cycle as shown above. For start up and early stage companies the investors are typically family and friends, business angels, and occasionally venture capitalists. It is highly unusual to find publicly listed companies and traditional capital markets investing in start-ups and early stage companies because of the high-risk profile:

The first risk is the company’s stage of development in the life cycle. Infant organisations have a high mortality rate. The second risk is management risk. Can management carry out the plan that it put forward? Do they have the ability, the experience, the background, the track record to accomplish the forecast and sales? (In Cytech, management had not been in business before on their own. They were in an industry in which they had no experience). For Angel financiers this is fine because they have a spread of investment. For a public company, it is an opportunistic high-risk investment. The third risk to evaluate is product and technology risk (in the case of Cytech, the company was using the software of Micro Gaming. When they changed software in September 2001 the technology risk escalated). The fourth category of risk has to do with the market and industry. Is the industry established and mature or is it a new industry? The risk is higher in

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 6 the latter. The fifth risk depends on the company’s ability to meet its sales projections. The sixth risk is financial risk.

The failure rate of early stage companies is high. How many investments should be made in order to safeguard the investments of companies engaging in early stage investment. In the United States, the answer is at least 20 early stage deals to get a real winner. If you only invest in one deal, you are likely to lose your money, according to experienced angels. “Early stage investing is like drilling for oil… you can’t do just one”. “It’s absolutely critical to do multiple deals”, Bill Sahlman of the Harvard Business School.

Corpcapital did not have a strategy for early stage investing, they had not previously been in this type of investment, and had very little skills in this area. But they did have grandiose dreams. Investing in early stage ventures in a public company would at the least have required an “early stage venture fund” and a plan to invest in at least 20 such opportunities. Instead, the executives invested in only one opportunity. They did not have experience in this category of investment themselves, and added to the risk by going into partnership with close friends, who were also inexperienced. They then treated the investment as a stable company using valuation methodologies better suited to prime and stable company.

Further risks in early stage investing

Unsystematic risk generally involves assessments at 3 levels: Macro environment, Industry and Company.

The extent of analysis of the macro environmental risk is dependent on the influence that these issues exert on the companies performance. The issues include regulatory, political, cultural and technological factors. The serious regulatory issues in the US were glossed over in projecting profits for Cytech. No in-depth analysis appears to have made of the technology risk in changing the software from MGS to IMS. Analysis at the industry level examines the overall attractiveness of operating in a selected industry and the company’s relative position versus its competitors in that industry. The purpose of the industry analysis is to identify and analyse how industry factors will affect a company’s ability to compete. No analysis seems to have been done to assess the factors which would most likely lead to success, nor why some competitors were more successful than others. The analysis of strengths and weaknesses within the company itself should take

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 7 into consideration the external economic and industry factors that have been described. A proper internal analysis will look at the company’s historical performance, paying particular attention to the causes that have created the results. This does not seem to have been done. When the forecast results were not forthcoming, management merely forecast more aggressively. The analysis by Corpcapital of the 3 levels, economic, industry and company, was selective and overly scientific for an early stage company. It tended to bring in external comparatives which favoured its case. Many of these comparatives and benchmarks do not stand up to scrutiny in the full context of Cytech.

In pricing out non-public companies – that is, companies whose stock is not traded publicly – some appraisers, in trying to use CAPM methodologies, tried to find “comparables”, public companies that “looked” like the candidate operationally. They then “borrowed the betas” of those companies in assessing the systematic risk component of total risk.

There are five things wrong with this. First, true operational comparables between traded and non-traded companies are difficult to find. Second, selecting the particular beta to be used is a very real problem because five or six different beta series are published, all based on timing differences. Third, if a high beta represents high risk, it should also correlate with high return. Yet it seldom does, even with manipulation of timing differences. Fourth, some analysts say flatly that both betas and standard deviations penalise funds and firms for variations in upside performance. Fifth, betas change. Betas should be used cautiously in assessing risk because they do not properly describe systematic risk. Anyone who uses a beta as a proxy for a major component of risk in setting a purchase or selling price is taking a major risk of being wrong.

Corpcapital applied too much science in an attempt to justify the end result that they desired. Unfortunately, the asset being valued was inherently incapable of being valued objectively and scientifically. This fact was disguised by the hyper-technical methods used. There was no reality check made after the event.

Difficulties of valuation in early stage companies

The best test of a valuation is whether the company at that price can be sold. In valuation, subjective factors simply eclipse objective factors. Determining value in early stage investing is highly subjective because so much depends on something that has not yet happened. There is no track record. In early stage companies, value lies in the future. It

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 8 has not yet been created. The best that valuation can offer are rules of thumb. Entrepreneur forecasts often prove faulty. Their elaborate, high math calculations can engender a false sense of precision, because their forecasts are often based on questionable assumptions. Such subjectivity renders less useful the established valuation formulae, which depend on more precise data and calculations, such as DCF. Angel investors in the United States discount entrepreneurs’ projections by 25% and sometimes up to 75% and more when they calculate valuation.

Greed and the entrepreneurs’ loss of ethics

Management of the operating company experience severe pressure to produce financial profits more quickly than the curve of development in the market allows. Therefore instead of building sustainable companies many of today’s high tech start-ups and their founders are more interested in playing the capital market for a quick buck. Management teams and their backers are more concerned with building market capitalisation than with building companies. Generally accepted accounting principles offer wiggle room to greedy entrepreneurs to exercise financial legerdemain.

According to Hamburger, Tal Harpaz (“Harpaz”), Sean Rose (“Rose”), Evan Hoff (“Hoff”), Martin Sacks (“Sacks”) and himself have had a close friendship since university days. It is a close circle of clever, young and aggressive people, with a penchant for entrepreneurship and the fast buck. Throw in Liebesman, Benji Liebmann (“Liebmann”) and Errol Grolman (“Grolman”) with the power of a publicly listed company. Add the 1998 environment of Nasdaq and the dot.com era and the warning lights were bright. These circumstances in a publicly listed company called for circumspection and the highest level of disclosure. Neither happened.

Fundamentals

The problems lie not only with the valuation models used, but with the assumptions made for the future, and with the other information fed into the model. No more inputs should be used than are absolutely necessary to value an asset. Models don’t value companies – people do. The claim, therefore, that the right model is being used is no safeguard that the right result will be produced. Separating the information that matters from the information that does not, is almost as important as the valuation models and techniques that are used to value the firm. There can be significant differences in outcomes, depending on which approach is used. Therefore choice, criteria and context are

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 9 important. Valuation requires oversight. Estimating investment risk involves including in the discount rate the certainties and uncertainties of receiving a future stream of earnings or cash flows investment. The lower the certainty, the higher the discount rate; the higher the certainty the lower the discount rate.

Essential Elements

An early stage investment opportunity has four essential elements. If only one of the elements is out of sync, failure is predictable.

People

Context

(Business) Opportunity Deal/Valuation

People

The people in the deal, including the entrepreneur, team members, investors, advisors, and any significant stakeholders.

The executives of Corpcapital worked with the entrepreneurs, Harpaz and Rose, but the Board of Directors of Corpcapital and shareholders were left out of the equation and were not protected. There were no external checks and balances.

Business opportunity

The potential business opportunity, which includes the business model, the size (which implies the potential returns), the customers, and the window within which it can be seized.

The business model was opportunistic. The initial transaction with Micro Gaming Services was changed when it became clear that the company was consistently missing its forecast. Management moved from one software system to another to

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 10 save costs. In the process, risk multiplied. Management however, did not treat Cytech as an early stage investment. They were in a hurry. As the gap between expectation and actual results grew, management did not change the assumptions. The forecasts simply became more and more optimistic relative to the escalation in risks.

Context

The macro-situation, which includes external factors, such as: technology development, customer desires, the state of the economy, industry trends, etc.

The macro environment was misread because it contained signals that management did not want to hear, such as the credit card issue.

Deal / Valuation

The structure of the deal, its terms and pricing.

The initial and subsequent structure of the deal is not fully known. There are no share certificates and signed agreements. The Cytech transaction stands in contradistinction to every other deal transacted by the management of Corpcapital. We are told in great detail of the huge efforts made by Corpcapital and the number of overseas trips made by Liebesman and Hamburger. For this, Corpcapital received 47.5% and Hamburger nothing.

The diagram below illustrates the sub-sets of the four essential elements. The triangles are all sub-sets of the macro environment relating to context.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 11 The team Stakeholders Entrepreneur etc.

People Competition Regulation

Technology The economy Conte xt

Deal Business opportunity

Price Timing Size Structure Customer The model

In summary, Corpcapital worked closely with the entrepreneurs of Cytech, but stakeholders were left out of the equation. With regard to context, the changes in US regulations, and the change in software technology, were not assessed correctly. With regard to the initial deal, the structure selected made no sense to an investment bank such as Corpcapital. The business opportunity should have been put into either an “angel fund” or “early stage venture capital fund”.

1.2.1.4 DCF is recognised as conceptually the most appropriate method of valuing a business. (Statement, point 127, page 28)

DCF valuation is easiest to use for companies that are in a more mature phase of their life cycle, and whose cash flows are currently positive and can be estimated with some reliability for future periods, and where a proxy for risk that can be used to obtain discount rates is available. The further we get from this idealised setting, the more difficult DCF becomes.

The biggest problem in using DCF valuation models to value private firms is the measurement of risk. The relationship between risk and WACC is impossible to synchronise for an early stage company, and difficult to justify.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 12 DCF is an excellent method of valuing a strong going concern where a sale is contemplated. The result serves at least as the take off point for bargaining out the price of a company. It also is an excellent check and balance in M & A activity, especially when both sides, buyers and sellers use it. DCF is used most often in M & A activity. Both sides use the DCF method because of the incompatibilities of their respective accounting techniques and methods. DCF is only interested in future cash flows. The major benefit of DCF in this situation is that there is a check and balance. Both buyer and seller are using the method, and use the outcome as the starting point for negotiations.

DCF calculations are quite complicated, and can give valuers a false sense of precision should any of the assumptions be questionable. The accuracy of this method depends on the quality of forecasts attained, and the assumptions upon which they are based.

Regardless the amount of number crunching an entrepreneur undertakes to obtain a reasonable monetary value for the business, the real value of the firm today is what someone else is willing to pay for it. The fact is, that despite many attempts to sell Cytech or merge it or list it, all of these efforts failed.

Terminal Value

The use of terminal value assumes that a growth rate, labelled stable growth, can be sustained in perpetuity. This permits an estimate of the value of all cash flows beyond that point as a terminal value for a going concern. For young companies, the key question is the estimation of when and how this transition to stable growth, if it is likely at all, will occur for the firm that is being valued.

DCF valuations tend to have an optimistic bias and the likelihood that the firm will not survive is not considered adequately in the valuation. With this view, the DCF value that emerges from the analysis overstates the value of the asset and has to be adjusted to reflect the likelihood that the firm will not survive to deliver its terminal value, and maybe not even positive cash flows that have been forecast in the first few years.

If someone wanted to start a valuation with an end number in mind, the terminal value is the easiest to manipulate. Relatively small adjustments will have massive consequences because of the compounding effects. The assumption that a firm will

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 13 be a going concern and continue to generate cash flows into perpetuity, is often suspect when valuing young companies, since many of them will not survive. Once a stabilised return is achieved, the DCF capitalises all returns beyond the forecast period as the terminal value. The relative size of the terminal value increases as the forecast period decreases, and becomes increasingly less important as the forecast lengthens. In the case of Cytech, only 3 years were projected. The fourth year to perpetuity was increased at a rate of 3% p.a. Such an approach inevitably creates a huge terminal value relative to the total value. In the case of Cytech it was the largest component of the DCF valuation. The terminal value involves a perpetual model – it assumes that the returns extend to infinity. One must therefore be very certain about the survival of the company to use this method. In the case of Cytech a terminal value was difficult to justify.

There is an explosive effect on value from what may appear to be modest changes in the long-term growth rate used to calculate terminal value. In the United States a 3% growth rate to establish the terminal value is considered to be aggressive, as it matches the growth of the economy. Where an infant organisation is not likely to survive, even 0% growth may be aggressive. In the case of Cytech a 3% growth rate into perpetuity is difficult to defend. There was always a question about the survivability of the company, and this became more relevant as time went by and risks escalated.

Andrew Blair, a successful early stage investor in the US, ignores “academic” valuation techniques such as DCF. He says “it is a different language when it comes to start ups and early stage investing”. Blair’s assessment of valuation methodologies is:

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 14 Cost High OH method $2 - $5m angel standard/Howard’s $5 Limit Travel to the future

Berkus method y c a r $2 – 10m internet standard Pre-VC method u c c

A Cary thirds PE multiple Finger in the air Venture capital method Multiplier method Multiple on revenue 3 LO Discounted cash flow 2 LO Low 1 HIG Low Complexity High DCF is highly complex, particularly for early stage companies, because of the large number of variables that need to be taken into account. These variables include the future forecasts of cash flow, discount rates, terminal growth rate and the assumptions underlying all these factors. Cytech itself is an excellent example of not only the complexity of this method, but its inaccuracy and inappropriateness for valuing early stage companies. Not only did Corpcapital use the most aggressive method of valuation, namely DCF, they also combined it with an inappropriate accounting policy, namely marked to market.

For these and many other reasons, Cytech could not be “measured reliably”. Corpcapital had joint control and significant influence, and therefore it was obliged to use the equity accounting method or cost.

There is only one circumstance where DCF valuations would be appropriate for an early stage company. This would be where the company is being disposed of and both buyers and sellers are using DCF to establish a starting point for negotiations. In this situation the natural check and balance exists in having two parties at arms length determining the price, and challenging each other’s assumptions on the same asset.

“One-Off” Adjustments

The Corpcapital forecasts of future earnings were based on the presumption that “one- off” adjustments were legitimate, and that the benefit of these adjustments could be taken in full to the future and compounded in the DCF calculations. However, management, who conducted the valuations, were both judge and jury on this issue, and there were no external checks and balances. Management benefited from the valuations by way of the

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 15 bonus pool in 2000, and therefore had a conflict of interest. They should not have been the ultimate custodians of the valuations. A $1m “one-off” adjustment in year 1 of the model used by Corpcapital would result in approximately $5m, or R34m at an exchange rate of 7, being added to the end valuation. The calculation was done roughly by Dave Collett (“Collett”) and was based on the same assumptions used by Corpcapital. The valuations will be dealt with in detail in due course by Collett.

The issue is when is it legitimate to make “one-off” adjustments, and when not? If an exercise is being conducted on an historic basis to compare true operating profits, it would be legitimate. In the annual financial statements of publicly listed companies there are circumstances where it is also legitimate, because nothing turns on it other than to let the shareholders know the status after adjustments compared to the status before adjustments. However, this practice is questionable when the adjustment is made to profits which are forecast in a DCF valuation. Here each adjustment is subjected to a severe compounding effect. Under these circumstances a proper check and balance, even external if necessary, would be required to establish the legitimacy of the adjustments. The adjustments were as follows:

PBT Adjustments Twelve months to August 2000 1732 72 Six months to February 2001 2345 690 Twelve months to August 2001 2615 1890 Six months to February 2002 1072 250

1.2.1.5 Earnings yield or PE valuation cannot adequately provide for future anticipated changes in the business, such as the future events like a re-negotiation of Aqua fees, change in royalty etc. (Statement, point 127.2, page 28) PE valuations use comparable data businesses and indices that are not strictly comparable. (Statement 127.3, page 28)

There are at least 17 valuation methods used by institutional investors to analyse public companies. In relative valuation, this method rests heavily on the assumption that the other firms in the industry are comparable to the firm being valued and that the market, on average, prices these firms correctly. This is difficult enough with stable companies. With early stage companies it is well nigh impossible. The PE value is easily available as a comparative, and hence is commonly applied. But it should only be used to compare a firm with others having similar (comparable) financial structures, accounting bases and position in the market. If it does not, the comparison is not valid.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 16 The availability of many methods of valuation imposes a duty of care on Corporate Officers, particularly where the outcome is material. The onus is on Corporate Officers to fully define the context and the parameters in making a choice of accounting treatment and valuation method. Corpcapital did not do this. It would appear that methods were selected which suited their own objectives. Furthermore, while independent oversight was essential. FHS, to all intents and purposes were part of the team and appear to have been influenced by management.

The selection of a method of valuation should:

conform to GAAP, be based on sound business judgement, given the full context of the investment, be recommended on proper external advice, particularly if the outcome of the valuation is material, and ensure that shareholder interests are protected, that the methods are appropriate, and the outcomes are fair and reasonable.

1.2.1.6 The PWC (London) valuation proposal provided a useful indication of the methodology they would recommend to value Netainment. PWC proposed performing a valuation based on DCF analysis supported by an analysis from comparable listed companies (Statement, point 127.5, page 28) In order to comment on the validity of PWC’s recommendation on DCF, it is necessary to determine whether or not PWC were provided with all relevant information on Cytech, including the full context. It is against this information that PWC would need to make their recommendation. It is difficult to understand why PWC were supporting valuations by an analysis from comparable listed companies. Cytech was a private start-up company and the listed companies were primarily UK full service gaming houses. The ABN Amro brokers report at the time of the Aqua listing supported a DCF valuation. (Statement, point 127.6, page 28) Subsequently, in January 2001, the Merrill Lynch report confirmed that the DCF model was appropriate. (Statement, point 127.7, page 28) Neither ABN Amro nor Merrill Lynch were specifically requested to provide expert advice as to the appropriate valuation method for Cytech. Their opinions relative to other companies are unlikely to be useful, even as indications. Subsequent events have, in any event, proved the Merrill Lynch opinions to be incorrect.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 17 1.2.1.7 I circulated the indicative valuation to the executives as a first draft (Mr Frangos was mistakenly given the first draft instead of the final version). (Statement, point 128.1, page 28 and point 128.1.1, page 29) Liebmann wanted a review by FHS prior to finalisation of the valuation. (Statement, point 128.2, page 29) On 17 August 2000, the Netainment valuation was debated with Peter Kay and executives. (Statement, point 128.3, page 29) The August 2000 valuation led to a significant increase in the valuation of Cytech, from R17m in February 2000 to R149m in August 2000. The materiality of the increase to old Corpcapital profits, required total transparency and independent expert opinions on the method of valuation to be used. Management was conflicted by virtue of the benefits they received in bonuses directly related to the Cytech valuations. With regard to the incorrect draft being given to me, the mistake was never rectified, even though it took place in June 2002 and the Cytech issue was intensely active until I resigned on 2 December 2002.

1.2.2 Merrill Lynch, Credit Suisse, First Boston, PWC (London) and other leading investment bankers actively analysed the industry and advocated the appropriateness of the DCF model for valuing investments in the industry. (Executive Summary, point 7.3) The only valid reason for the use of DCF valuations would be as a starting point for negotiations between a willing buyer and a willing seller. In such circumstances, both sides would be required to reveal the assumptions on which their valuations are based, and to debate the validity of them. One must assume that this may have been the motivation for the banks referred to having recommended the DCF method. It is unlikely that any of the banks would have recommended the method universally, without taking into account circumstances and context.

1.2.3 The valuation derived by DCF was benchmarked against ascertainable market values for substantially similar investments. (Executive Summary, point 7) The use of comparatives in the same industry for valuation purposes is extremely difficult for stable companies where predictiveness is reasonably reliable, and near impossible for early stage companies. Every company has its own uniqueness in the context of macro environmental factors, competition, leadership and management, market forces, products, pricing, channels of distribution, methods of financing and phase of life cycle. Therefore the use of comparatives requires a highly complex process of justification even under the most stable conditions.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 18 1.2.4 PWC gave me a verbal opinion early on. I also discussed it with FHS and they produced a draft opinion. FHS and I reviewed the prevailing GAAP statements and international accounting standards. (Statement, point 81, page 16) Were PWC given all of the circumstances related to ownership and control, that Corpcapital had on Cytech? Were they given the full context? And were they told the use to which valuations would be put?

1.2.5 We also had regard to market commentators’ reports which said that international best practice was for investment companies to mark their investments to market and reflect increases and decreases in their income statement. The uniform conclusion was that this was the best accounting practice and that accordingly, Corpcapital would adopt it. (Statement, point 81 and 82, page 16) If marked to market methods are used in publicly listed companies, or large divisions of publicly listed companies which are stable, then provided common standards are maintained, this method would have some merit. Public companies, and investment banks in particular, recognise that the marked to market approach creates a book value on an unrealised investment, and is not backed by cash flow. Cytech however, was a very early stage company, in highly volatile conditions of a new industry, where forecasting proved to be highly inaccurate. The use of aggressive forecasts inevitably leads to aggressive DCF valuations, and even more aggressive attributable profits resulting from the marked to market accounting method. Credible market commentators would not universally recommend the marked to market method without having regard to circumstances. It is doubtful that any would recommend it if they were aware that the accounting method would result in the inflation of the profits of a publicly listed company. Quite apart from the requirements of GAAP there are strong business reasons as to why DCF and marked to market were inappropriate for Cytech. Hamburger does not explain why in the first two accounting periods in the life of Cytech, he decided to use the PE Multiple method of valuation.

1.2.6 A fundamental tenet of this decision was that Netainment was held for sale in the near future. (Statement, point 83, page 16) At this point in Cytech’s life, it suited management to regard it as “held for sale in the near future”. The same management advised PWC at the August 2002 valuation that the “value in use” method should be used because Cytech was to be held for the long term.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 19 1.2.7 The first two valuations, August 1999 and February 2000, were carried out using the Forward PE Multiple method. (Statement, point 85, page 17 and point 92, page 20) The valuation methods used were PE Multiple method for August 1999 and February 2000; the DCF and marked to market method for August 2000, February 2001 and August 2001; the equity accounting method and DCF was used for February 2002 and August 2002. While using the PE method, a multiple of 3 was used for August 1999. This PE increased to 7 for February 2000. The discount rate and terminal growth rate were kept constant while using the DCF method despite the non-achievement of forecasts and the escalation of risk – a decision by management which could never be defended in open forum. After the accounting policy was changed and the equity method adopted, the DCF method continued to be used to value the investment in February 2002. The result of this valuation was a marginal reduction from R228 million in August 2001, to R221 million in February 2002. PWC presented a smorgasbord of 10 different valuations with a broad range allowing Tom Wixley (“Wixley”) and the Audit Committee to select their own value at 31 August 2002.

Hamburger increased the multiple used in the PE method from 3 in his first valuation to 7 in his second, without explanation. Thereafter, the PE method was abandoned in favour of DCF valuations and the marked to market accounting method, without any disclosure to shareholders. During this early period, the value of the asset went from R4.5m in August 1999 to R17m in February 2000 and R149m in August 2000.

1.2.8 In April 2000, I was instructed to analyse international pricing models and prepare forecast earnings in preparation for a London listing of Cytech. (Statement, point 103.2, page 22) This is evidence of management’s preoccupation with market capitalization rather than building the business.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 20 1.2.9 In May 2000, I received an instruction from Exco to have an independent expert value Netainment. However, the old Corpcapital board decided not to proceed because of the substantial expense of a third party valuation, given Corpcapital’s internal expertise and the role played by Corpcapital’s auditors to audit the internal valuation. (Statement, point 109, page 25) Exco must have known that both the method of valuation and the valuation itself would have a significant impact on the profitability of old Corpcapital. They were also in the midst of substantial restraint of trade payments at that time, and knew that they stood to benefit substantially from the valuation through the bonus pool. The decision of the Old Corpcapital Board not to proceed with an independent valuation, on the basis of a flimsy reason, was irresponsible. The only non-executive director on the Board of Old Corpcapital was Wim Trengove (“Trengove”).

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 21 1.2.10 In August 2000, I developed the financial model used to determine the indicative valuation of Netainment. (Statement, point 119, page 27) It was debated internally at operational and Exco meetings. (Statement, point 120, page 27). This was Corpcapital’s first attempt at a comprehensive DCF valuation of Netainment (Statement, point 121, page 27) I was particularly aware that this valuation would provide a benchmark and framework for all future valuations. The methodology would need to be consistently applied in future periods. (Statement, point 122, page 27) My valuation methodology and assumptions would need to withstand scrutiny from within Corpcapital and from out auditors. (Statement, point 123, page 27) When I developed the valuation model, I believed we were going to get an external advisor to prepare an independent valuation. (Statement, point 123, page 27) I consulted with Shane Kidd. (Statement, point 125, page 27) I concluded that DCF was the most appropriate valuation method. (Statement, point 127, page 27) There is a stark contrast between Hamburger’s detailed explanations of the comprehensive internal process that was followed to determine valuation models on the one hand, and the lack of communication and transparency between management and the Board of Directors on the other hand. It is almost as if management were planning to adopt the valuation method that best suited them, while keeping the Board of Directors in the dark. Where materiality is concerned, communication with the Board is mandatory. Where there are conflicts of interest involved, in addition to materiality, full and transparent communication is essential to protect shareholders. The internal process is not a substitute for good governance and the exercise of fiduciary duties.

1.3 Valuation Methodology (Appendix 2, pages 59 and 60)

The methods of valuation used were inappropriate and have been covered in detail by Brian Abrahams (“Abrahams”) and Collett. The comments made in this section therefore should be viewed in this light.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 22 1.3.1 Three years of forecast earnings were discounted, and a terminal value calculated using Gordon’s Growth Model. The terminal value represented the higher of the two values in the final DCF valuation. This will always occur when the forecast period is kept short, e.g. three years. This is the way the mathematics works. However there appears to be no discussion or explanation as to why it was believed that Cytech would survive into perpetuity. The use of a perpetual model cannot be used without an explanation as to why the company is assured of survival, and a full justification of the terminal growth rate, if it passes the first test. This omission is even stranger from 2000 onwards as it became apparent that the company was not achieving forecasts and the risks were growing exponentially. A terminal value would be difficult to justify in these circumstances.

1.3.2 Forecasts were prepared using historic sustainable earnings (excluding non- recurring expenses) as a base. The term “sustainable earnings” is associated with stable companies that have a significant track record against which to measure. The non-achievement of forecasts over such a long period of time indicates that sustainable earnings could not be forecast reliably for Cytech. Mention is made of non-recurring expenses. These were expenses which occurred in the normal running of the business in my opinion. “One- off” adjustments are not appropriate in every situation based on the notion of management. Where the adjustment is made to profits, which are then used as a base to be compounded into the future in a DCF valuation, then the adjustment is not appropriate.

1.3.3 Profits assumed to approximate cash flows, on the assumption that capital expenditure would approximate depreciation, and working capital would be neutral.

1.3.4 Assumptions based on historic performance of the business and nature of the business. The key assumption relates to the generation of revenue. Since revenue forecasts were never achieved, the underlying assumptions were not reliable.

1.3.5 Valuations incorporated the assumptions that market participants would use in their estimates of fair value. How does he know this?

1.3.6 Forecasts for the three years compiled taking into account: a. reasonable estimates using industry background b. operational issues

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 23 c. analysts reports d. historical performance e. operational management input f. relevant operational initiatives It is a style of management to substantiate the “truth” of their statements by claiming “valid comparisons”, support of “industry reports”, and the blessing of people with “impeccable credentials”. However, in reality, assumptions have their own internal dynamics and are capable of being evaluated on this basis. For example, reality indicates:

that early stage companies are unpredictable (Cytech itself is an example of this), that there is no industry background to a new industry, that comparisons are seldom valid, and never in early stage companies, that attempts to apply science to inherently volatile predictions are doomed to failure.

1.3.7 Forecasts prepared in US dollars. Forecast depreciation of the rand:dollar exchange rate not taken into account.

1.3.8 Terminal value calculated using a 5% growth rate in August 2000 and a3% growth rate thereafter. Terminal growth assumption is based on a long-term inflation assumption for the US. See comments under 1.3.1. This approach was highly aggressive and not defendable.

1.3.9 The discount rate (“WACC”) used was conservative comparable to the prevailing rate of returns for financial characteristics, and was calculated using the Capital Asset Pricing Model for a dollar income stream. The comparison was flawed.

1.3.10 WACC of 24% used for all reporting periods. This comment is not correct. Amongst the range of ten valuations put forward by PWC in August 2002, were four valuations at a lower WACC, two at 18% and two at 22%. By August 2002, the risks had increased exponentially and this required a substantial increase in the discount rate, not a reduction. PWC merely accepted the management valuation.

1.3.11 In calculating the WACC, the additional risk premium was intended to take into account the risk in forecasting a relatively young business in a dynamic, developing industry.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 24 This was an attempt to apply advanced science to a volatile and unpredictable situation.

1.3.12 Turnover and earnings based valuations were also calculated with reference to comparable companies. A range of values was calculated after performing sensitivity analysis. This analysis is misplaced for early stage companies.

1.3.13 The DCF valuation was compared for reasonableness to turnover and earnings valuations. This comparison rests on the assumption that turnover and earnings valuations of early stage companies are reasonable, and that the companies being compared to are similar. This is unlikely on both counts. The argument appears to be that if one puts up a great number of invalid comparisons and approaches, they will eventually validate the methods used. A far simpler approach would have been to use equity accounting or cost price valuation in the first place.

1.3.14 There are active markets where equity interests in online gaming operations are traded, and from which operating trends could be extracted. I had regard to these to verify assumptions, forecasts and valuations for reasonableness after every valuation. If Corpcapital used the method of valuation to sell the company to a buyer who was using the same method as a starting point for negotiations there was some justification. As a method to determine attributable profits for a publicly listed company there was no justification.

1.3.15 Senior management of old Corpcapital reviewed the valuations, there were numerous informal debates, auditors and audit committee inputs, and approved by the Board. In the circumstances, internal reviews were inadequate. However scientific and hyper- technical the analysis was, it could not change the basic facts. These were that Cytech was an early stage company, its results were volatile and unpredictable, and the assumptions used were flawed. The analysis could not compensate for these inherent internal characteristics. To all intents and purposes, the Board of Directors of Old Corpcapital was an insider Board.

1.4 Integrity of valuations

1.4.1 We did not inflate valuations. We were not requested to do so. The sole purpose of the valuations was to arrive at an honest and reasonable valuation. (Executive Summary, points 5 and 6).

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 25 In the full context of Cytech, the only defendable accounting treatment from the outset was Equity Accounting or cost. The methods used by Corpcapital were inappropriate and resulted in profitability and valuations which did not reflect the true situation of the company. Furthermore, Hamburger was an interested party and his own remuneration was largely dependent on Cytech. In fact, Hamburger’s bonuses totalled R2.5 million over 2 years.

1.4.2 There was a proper process of control of the valuations, and a series of checks and balances. (Executive Summary, point 6). In the circumstances outlined, an exclusive process of internal control is insufficient.

1.4.3 FHS played an integral part. They conducted a review in August 2000, an audit in August 2001, and August 2002. (Executive Summary, point 6.2) FHS did not conduct an audit in August 2000. There was no audit in August 2001 or August 2002. The fact that FHS did not act in accordance with what shareholders would expect from an external auditor meant that the shareholders were unprotected.

The fact that FHS, according to Hamburger, paid an integral part, meant that Peter Kay (“Kay”) should not have been evasive about his answers to me. Kay told me that no audit had been done and that FHS had merely conducted a review.

1.4.4 The January 2001 Merrill Lynch report used material assumptions with respect to growth and discount rates which were more aggressive than those applied in the Corpcapital valuation of Netainment. The Merrill Lynch validated the approach, methodology and material industry assumptions in the Corpcapital valuations. (Statement, points 142 and 143, page 31) Not only were Merrill Lynch wrong, but also the comparisons used by Corpcapital do not appear to be justifiable. Merrill Lynch was involved in the valuation of UK publicly listed companies and their on-line divisions for radically different purposes than those used by Corpcapital. Merrill Lynch was not given a mandate to value Cytech.

1.4.5 In 2001, KPMG tested my February 2001 valuation for reasonableness for the purposes of the Corpcapital Group merger. These findings were updated by KPMG in August 2001 (Executive Summary, point 6.5 and Statement, point 165, page 39) The KPMG report was used for the purpose of valuing old Corpcapital in arriving at the underlying swap ratios used in the merger. KPMG did not conduct a detailed, in-depth valuation or audit of the underlying investments of Old Corpcapital including Cytech. KPMG were provided with an indicative valuation of Cytech prepared in draft form

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 26 internally by the management old Corpcapital. This valuation contains a prominent disclaimer on the front page that it has been prepared on the basis of unaudited financial information supplied by, and in discussions with, managers and directors of Cytech and that the information incorporated in the valuation has not been independently verified by old Corpcapital.

Section 10 of the fair and reasonableness report prepared by KPMG specifies quite clearly in clause 10.3 that the valuation was prepared by Corpcapital and only reviewed by the auditors. It is clear from clause 10.3.12 that the opinion expressed by KPMG is based on information received from Corpcapital management and that no independent investigation into the underlying company was conducted.

The value of the fair and reasonable opinion by KPMG on Cytech is therefore no better than the valuation prepared by Corpcapital on the basis of unaudited and unverified information.

1.4.6 In 2002 PWC carried out an independent valuation. (Executive Summary, point 6.6) New information has emerged during the course of the Section 258 (2) enquiry, which indicates that it was Goldhawk who conducted the valuations of Corpcapital Bank to determine swap ratios during the merger. It is evident that when the Kensani objections arose, the management of Old Corpcapital called in Goldhawk to persuade Kensani that the swap ratios were fair and reasonable. Therefore as the independent valuer appointed by Wixley to carry out the Cytech valuation on 31 August 2002, Goldhawk could not have been impartial and objective, as he had previously approved the valuations. This throws a new light on Goldhawks’ work during the August 2002 valuations. It is appropriate to make the following comments on the PWC valuations:

PWC letter to Wixley dated 15 October 2002

1. The proper reasons for the independent valuation are not spelt out. The independent valuation arose out of my internal enquiry into Cytech. Management had carried out all previous valuations, and no audit had been conducted. PWC merely say: “it is our understanding that the management of Corpcapital will use the valuation to estimate the recoverable amount”.

2. “In estimating the recoverable amount we have assumed Cytech’s existing business to be ongoing”. No reasons are spelt out to back up this major

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 27 assumption, which has a significant impact on terminal value, and therefore the valuation as a whole.

3. PWC relied solely on information provided by management. Their conclusions therefore are dependent on the information being complete and accurate in all material respects.

4. The value in use method is used, based on the value of future cash flows, which are discounted, less the cost of disposal. PWC accepted management’s statement that Cytech was to be held for the long-term without explanation, even though it was a reversal of their previous standpoint.

5. PWC arrived at a before tax value in use of R120m, R84m after tax, and a net selling price of R86m before tax and R60m after tax.

6. PWC cite the following limiting conditions:

6.1 Valuations do not include an audit in accordance with GAAS of Cytech’s existing business records.

6.2 Forecasts relate to future events and are based on assumptions, which may not remain valid for the future. Consequently, this information cannot be relied upon to the same extent as that derived from audited accounts.

6.3 PWC express no opinion as to how closely the actual results will correspond to the forecasts by Cytech’s management.

Summary of international gaming companies taxation status

A table is presented, without explanation, as to why comparisons with Cytech are valid. Many of the companies are publicly listed gaming houses where their online division is a minor part of the business.

AC128 Valuation of Cytech (Version 1) (presented to Corpcapital without my knowledge)

Monthly revenue, $’000

Sept 00 2.348

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 28 Oct 00 2.128 Nov 00 2.403 Dec 00 2.981 Decline commences Jan 01 2.807 Feb 01 2.527 Mar 01 2.685 Apr 01 2.796 May 01 2.691 June 01 2.803 Credit Card issue July 01 2.701 Decline accelerates Aug 01 2.039 Sep 01 1.885 New software system Oct 01 1.750 Nov 01 1.442 Dec 01 1.724 Jan 02 1.611 Decline accelerates Feb 02 1.329 Mar 02 1.265 Apr 02 1.171 May 02 1.171 June 02 1.240 July 02 1.183 Aug 02 1.143

Sales first declined in January 2001. There was a dramatic downturn from July 2001. It was at this time that according to Hamburger a deal had been concluded with IMS to change the software. The software was officially changed in September 2001. Sales declined by 60% during 2002. Nevertheless, PWC still did not question the survivability of Cytech. Management indicated that the 60% decline in revenue was caused by:

The ban on the use of credit cards in the USA; and The change in software from MGS to IMS

The above reasons advanced by management are permanent factors which would affect revenues into perpetuity. PWC should have known this.

PWC concede that management’s forecast for 2003 is aggressive but accept revenue forecast to grow by approximately 10-14%. In addition, PWC accepted the 3% as the residual growth factor without justifying it. Even a zero percent in the circumstances would be aggressive.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 29 Income Approach – Detailed forecasts prepared by management for 2003- 2005

USD ‘000 2002 2003 2004 2005 Actual Forecast Forecast Forecast Total Revenue 16,914 15,351 17,436 19,572 Total Expenditure 14,722 10,856 11,635 12,927

Aqua administration fee 1,141 963 635 615 IMS royalty 1,486 1,100 1,135 1,272 CFI fee 1,358 1,090 1,217 1,366

Net income 2,192 4,495 5,801 6,645

PWC do not present historic comparisons or any analysis of forecasts against actuals even though they had the figures. The picture presented is superficial and aggressive:

The growth in revenue is not justifiable on past performance Management have shown a significant reduction in the Aqua fee. Aqua was a publicly listed company at the time and this assumption is not backed by any formal agreement with Aqua nor a statement by PWC that Aqua had confirmed the reduction. Prior to the cancellation of the MGS license, Cytech was paying MGS some $750,000 per month, or in excess of $8m per annum. The IMS royalties are a fraction of this amount. Management then indicates that the IMS software license is also being renegotiated. Given the record that all agreements and audits in Corpcapital appear to be in draft and never signed, PWC should have obtained confirmation from the third parties referred to by Corpcapital.

The profit forecasts are aggressive and not sustainable. PWC do not incorporate a notional tax, even though a strong argument was put to them by me on this matter in August 2002. In the second version of their valuation, they then retract on this matter.

Market Approach

PWC accept at face value management’s forecast earnings for 2003, and that “management is confident that the earnings are achievable. This amount is regarded as sustainable earnings”. PWC then use comparatives to verify valuation, but no logical reasons are put forward as to why these comparisons are valid. It is not sufficient justification that the companies with whom PWC is comparing merely happen to be in the same industry.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 30 Issues for discussion

PWC table the issues for discussion, but do not state whether these discussions took place, and what the conclusions were. A selection of the issues are:

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 31 Uncertain regulatory environment Industry shake out and consolidation expected New products could be a key for the future Key man risk No written Shareholder’s Agreement (this is a surprising statement by PWC. It is not possible to carry out a valuation in the absence of a Shareholder’s Agreement). Impact of new IMS software on Cytech’s value Current negative trend in Cytech revenue

Summary of valuation scenarios

Management forecast plus international average CPI growth after 2005 at 18% discount rate, R227m ($46m). Hamburger’s statement indicates that a discount rate of 24% is applied throughout. Now management, despite a significant increase in risk and the non-attainment of forecast, have reduced the discount rate to 18%. Management forecast plus international average CPI growth after 2005 at 22% discount rate, R183m ($37m). Management forecast adjusted to reflect current revenue levels at cost structure at 18% discount, R153m ($31m). Management forecast adjusted to reflect current revenue levels at cost structure at 22% discount, R123m ($25m). 2002 PAT at 6 PE, R65m ($13.2m). 2003 Management forecast PAT at 6 PE, R126m ($25.6m). 2002 PAT at 8 PE, R67m ($17.5m). 2003 Management forecast PAT at 8 PE, R168m ($34.1m). 2001, 2002 and 2003 three-year average PAT at 6 PE, R108m ($21.9m). 2001, 2002 and 2003 three-year average PAT at 8 PE, R144m ($29.2m).

None of the above methods of valuation were appropriate for Cytech. PWC should have come to the conclusion on the basis of facts presented to them that the investment could not be measured reliably. The implementation of the methods of valuation used by Corpcapital were not in accordance with GAAP. The survivability of Cytech was in serious question at the time that PWC did their valuations, and therefore a terminal value could not in these circumstances be applied, even if the methodology was appropriate, which it was not.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 32 AC128 Valuation of Cytech (Version 2) (presented to Corpcapital after my discussions with Goldhawk)

There are two versions of the PWC valuation. The first valuation was given to Corpcapital without my knowledge and without a copy being given to him. I saw Goldhawk on the same day and expressed my opinion that there were several areas in the valuation methodology used by PWC which were not logical and that he did not agree with. Amongst other matters, the question of notional tax was raised with Goldhawk. My view was that a notional tax should be applied to all calculations because if there was to be a purchaser it was almost certain to be a UK gaming house, and they would be taxed on the income from the investment. As a result of these discussions, Goldhawk issued a second version of his report where the figures were reduced.

The valuation methodologies applied by PWC was not appropriate. The following changes took place between the two documents:

Additional factors to be taken into account

Management indicated that the transfer to the IMS software contributed to the 60% decrease in revenue in 2002. The IMS software has a lower lifetime value per player than the Micro Gaming software. This may negatively impact on future revenue and marketing expenditure forecasts. The IMS contract is for a minimum of 7 years and carries very onerous cancellation terms. We have not been provided with copies of the contracts with Aqua and CFI. There is no written Shareholder’s Agreement which can have a negative impact in the event of any dispute. The financial statements of Cytech and its predecessor, Netainment, have to the best of our knowledge, never been formally audited. We have therefore had to rely on unaudited management accounts and representations. If the investment in Cytech is deemed to be an asset held for disposal, one needs to take cognizance of the potential attitude of the buyer toward the tax regime of the company. It would be reasonable to assume that a buyer would be a corporate operating in a tax regime, which would not be able to take advantage of the specific structure in place for Cytech.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 33 I therefore believe it appropriate to include as an assumption, in any of the scenarios, the tax rate of 30%.

The changes between the first and second PWC reports are so material that they throw a new light on the valuations. In the circumstances, it is questionable whether either of the reports are valid.

Revised Valuations

Management forecast plus international average CPI growth after 2005 at 18% discount rate, R159m ($32.2m). Management forecast plus international average CPI growth after 2005 at 22% discount rate, R128m ($25.9m). Management forecast adjusted to reflect current revenue levels at cost structure at 18% discount, R107m ($21.7m). Management forecast adjusted to reflect current revenue levels at cost structure at 22% discount, R86m ($17.5m). 2002 PAT at 6 PE, R46m ($9.2m). 2003 Management forecast PAT at 6 PE, R88m ($17.9m). 2002 PAT at 8 PE, R47m ($12.2m). 2003 Management forecast PAT at 8 PE, R118m ($23.8m). 2001, 2002 and 2003 three-year average PAT at 6 PE, R76m ($15.3m). 2001, 2002 and 2003 three-year average PAT at 8 PE, R100m ($20.4m). 2002 PAT at 5 PE, R39m ($7.6m).

Conclusions

Goldhawk was conflicted because of his past involvement in the controversial valuations at the time of the merger, and therefore he should not have been appointed as the independent valuer of Cytech by Wixley. A serious internal enquiry initiated by a non- executive director would require total independence and objectivity in the process to be used.

Wixley then gave custody of the process to management, and Sacks in particular. This was not appropriate. It is apparent that management had undue influence in the valuation.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 34 None of the methods of valuation used by PWC were appropriate because the investment could not be measured reliably, a conclusion that PWC themselves should have come to.

It would appear that management were seeking to value the asset at R150m in order to disguise the declaration to shareholders of the change in accounting policy. If the investment was valued at R150m, they would be able to claim a normal impairment over three years, from a base of R228m. There appears to be no other explanation as to why the discount rates were reduced in more adverse circumstances in two of the PWC valuations.

PWC used the “value in use” method. This method is sometimes used when an investment is to be held indefinitely. The evidence provided by Hamburger indicates that the investment was held purely for resale. In fact Hamburger’s statement shows the number of times Old Corpcapital tried unsuccessfully to sell Cytech or merge it. The rationale advanced by Corpcapital for this significant shift in strategy is that the investment is being kept for use following the change in accounting policy in February 2002. In recent times, Corpcapital has again changed its strategy and is in the process of unbundling the entire company. It appears that strategies were devised for valuation purposes rather than for setting the direction of the business.

1.5 Audit Initiatives (Appendix 3, pages 61-64)

1.5.1 Netainment is a Netherlands Antilles company and is not required by statute to produce audited accounts. Sean and Tal, therefore, felt no need to produce audited accounts. Harpaz and Rose should have been informed on a non-negotiable basis at the outset that their partner, old Corpcapital, required fully audited accounts each year. Instead the audit and disclosure to shareholders became secondary to Harpaz and Rose’s tax dodging, to which Corpcapital were party.

1.5.2 I exerted pressure on Sean and Tal to prepare audited accounts. The facts are that there were no audited accounts.

1.5.3 The audit of Netainment was essential for the purpose of finalising Corpcapital’s own audited accounts. Hamburger accepts the necessity for an audit but never succeeds in getting Cytech audited.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 35 1.5.4 I was instructed by Exco to have Netainment audited. Even in July 2000 Shane reminded me, and stressed the timing. Shane constantly followed up and continued to pressure Sean and Tal. This explanation is not credible.

1.5.5 During the English Harbour negotiations, Insinger advised us to have audited accounts for the AIM listing.

1.5.6 When it became apparent that a Netainment audit would not be done timeously, we discussed an alternate approach with FHS. FHS agreed that they could derive sufficient comfort from a comprehensive review. FHS did not act in accordance with their fiduciary duties as the independent check and balance that shareholders were entitled to expect.

1.5.7 I approached PWC (Johannesburg) to do an audit. They referred me to their London office. Although initially keen, PWC (London) could not get approval from its international compliance department. One can only assume that the approval was refused because of non-compliance. The reasons are not volunteered.

1.5.8 I approached PKF to do the audit and they confirmed they would. Sean and Tal did not want to incur the cost, and there was no sense of urgency from them. The investing public is entitled to believe that the signatures of directors and auditors on publicly listed companies financial statements means that they have applied their minds and their fiduciary duties of care and skill, and that the accounts are an accurate portrayal of the state of affairs of the company. The investing public are therefore able to make their decisions against the background of the true state of affairs of companies. Management is under an obligation to take whatever steps are required to achieve this status. That partners in an unlisted entity merely do not want to incur the cost, or have no sense of urgency, is unacceptable. If this were to be the case, the directors and auditors would have had to qualify the accounts.

1.5.9 Paul Sudolski of English Harbour also put pressure on for an audit.

1.5.10 FHS was engaged to perform a review of Netainments results for August 2000 to give comfort for Corpcapital’s audit requirements. FHS did not conduct an audit. A review is insufficient to give comfort.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 36 1.5.11 In December 2000, I wrote to Sean and Tal informing them that PKF would perform the audit. However, the English Harbour merger was terminated, and as a result the benefits of a London audit were outweighed by the cost. Hamburger himself now feels that an audit was not necessary.

1.5.12 FHS were engaged to audit Netainment at September 2001. Summary of FHS “work”. Either FHS did not conduct the audit, or the audit was not completed.

1.5.13 FHS performed sufficient work to satisfy themselves that the accounts could be relied upon and used for valuation purposes. This is an inadequate and unacceptable substitute for an audit.

1.5.14 As Netainment outsourced the majority of its operations to third parties, the auditors could rely on the Netainment income statement. This is an inadequate and unacceptable substitute for an audit.

1.5.15 For August 2001 an audit was conducted. FHS issued draft financial statements. In February 2002 final audit accounts were presented for sign-off by corporate directors. This responsibility was given to Shane Kidd and Ruth Credo to implement. The audit for August 2001 was not conducted, and nor for February 2002. There was no sign-off.

1.5.16 FHS conducted an audit at August 2002 of Cytech. To my knowledge this was not done. If the accounts were not signed there was no audit. The process was not completed.

1.5.17 FHS conducted a further audit at September 2002. Not to my knowledge.

1.6 External Valuations (Appendix 4, page 65)

1.6.1 Exco instructed me to have an external valuation on 12 May 2000. This was repeated on 14 July 2000. The instruction was not carried out.

1.6.2 I was in discussion with Arthur Anderson, PWC and KPMG. Nothing came of these discussions.

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 37 1.6.3 I approached PWC (London) to do a valuation. They made a proposal in June 2000, but the fee was high. Peter Kay then advised against the audit. His rationale was that Corpcapital must value the asset consistently with accounting practice. He said the cost outweighed the benefit. His attention would provide the necessary independent attention. Did Kay in fact advise against the audit? If he did, he was not acting as the appropriate external check and balance shareholders are entitled to. FHS should have qualified the accounts of Old Corpcapital. The statement attributed to Kay is extraordinary: “His feeling was that the cost of the external valuation would outweigh any benefit from having the valuation done externally.

1.7 Summary of the relevant facts and circumstances at each material valuation date

1.7.1 To August 2000, everything was positive. (Executive Summary, point 12, August 2000) Cytech was a start-up company in 1999 and 2000, and an early stage company thereafter. It was operating in a new and emerging industry. These circumstances were not adequately taken into account in preparing forecasts.

1.7.2 To February 2001, everything continued to be positive. (Executive Summary, point 12, February 2001) Sales declined in January and February 2001. This was not taken into account. The risk of a credit card transaction ban in the US become more real. The risks had increased.

1.7.3 To August 2001: 1.7.3.1 the change to the software platform was a fundamental change to the business; 1.7.3.2 revenue had flattened; 1.7.3.3 US credit card issues were known; 1.7.3.4 nonetheless the business was expected to be more profitable. (Executive Summary, point 12, August 2001) Notwithstanding the significant increase in risk profile arising from the factors identified above, management did not change the fundamental assumptions in the DCF model. The expectation to increase profit, despite the additional risk, was unjustifiable.

1.7.4 To February 2002: 1.7.4.1 the new software was accepted; Subsequently management reported that the change to the new software was a failure. The circumstances and difficulties associated with the change were apparent at the time, and capable of assessment. In fact the decline of 60% in revenue in 2002 was attributed largely to the change in software. The change in

D:\Docs\2018-04-13\0ddb38d8221293f1d6e390610fd8f459.doc page 38 software was to an inferior regime and these facts were well known within the industry at the time. Micro Gaming was acknowledged as the industry leader with outstanding software. What has not to be disclosed is the material inconvenience factor to customers arising from the changes in software. The name “King Solomon’s mines” vested in MGS. Cytech, therefore, had to develop a new website and to cross-reference the two sites. If a user moved to the new site it took at least an hour to download the IMS software. The user would then have to go through a long registration process and banking verification. This was no short, smooth process. It is not surprising that the cost in lost users was high.

1.7.4.2 revenue was slightly down; Revenue was significantly down.

1.7.4.3 the industry was softening as a result of previously unforeseen changes. (Executive Summary, point 12, February 2002) The risk profile had increased further and yet the fundamental assumptions remained intact.

1.7.5 To August 2002: 1.7.5.1 an independent valuation was carried out by PWC. The valuation was carried out as a result of a serious and deep enquiry by a non- executive director. It was anything but the routine independent evaluation implied.