CITY of LAWRENCE 2009 OPEN SPACE and RECREATION PLAN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MMI 53 River Street Dam.Pdf

TOWN OF ACTON JUNE 7, 2019 | ACTON, MA PROPOSAL Studies Related to the Dam Located at 53 River Street June 7, 2019 Mr. John Mangiaratti, Town Manager Town of Acton Town Manager’s Office 472 Main Street Acton, MA 01720 RE: River Street Dam Removal and Fort Pond Brook Restoration Acton, Massachusetts MMI #4458-02 Dear Mr. Mangiaratti: The Milone & MacBroom team of structural engineers, bridge scour experts, geotechnical engineers, and hydraulic engineers are uniquely qualified to design the dam removal, and evaluate the potential upstream and downstream infrastructure impacts associated with the removal of the Dam at River Street to improve ecological functions of the Fort Pond Brook. When reviewing our proposal, we ask that you consider the following: Our team brings expertise and a proven track record of success in dam removal projects throughout New England. Milone & MacBroom professionals have backgrounds in hydrology and hydraulics, engineering design, fisheries expertise, and wetland biology. Our staff also includes invasive species experts, fisheries biologists, and permitting specialists. We also integrate the creative innovation of our extensive in-house team of landscape architects and frequently include passive recreational park features at our dam removal sites. We have the ability to integrate dam removal with the natural site opportunities through careful analysis and planning so that your project is technically sound, environmentally sensitive, and aesthetically pleasing. Our team of experts has performed many dam removal projects throughout New England and the Northeast. Milone and MacBroom are pioneers in the field, having completed our first dam removals in the 1990s. With over 40 constructed dam removal projects, we have completed more than any other design firm in the Northeast. -

Concord River Diadromous Fish Restoration FEASIBILITY STUDY

Concord River Diadromous Fish Restoration FEASIBILITY STUDY Concord River, Massachusetts Talbot Mills Dam Centennial Falls Dam Middlesex Falls DRAFT REPORT FEBRUARY 2016 Prepared for: In partnership with: Prepared by: This page intentionally left blank. Executive Summary Concord River Diadromous Fish Restoration FEASIBILITY STUDY – DRAFT REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Project Purpose The purpose of this project is to evaluate the feasibility of restoring populations of diadromous fish to the Concord, Sudbury, and Assabet Rivers, collectively known as the SuAsCo Watershed. The primary impediment to fish passage in the Concord River is the Talbot Mills Dam in Billerica, Massachusetts. Prior to reaching the dam, fish must first navigate potential obstacles at the Essex Dam (an active hydro dam with a fish elevator and an eel ladder) on the Merrimack River in Lawrence, Middlesex Falls (a natural bedrock falls and remnants of a breached dam) on the Concord River in Lowell, and Centennial Falls Dam (a hydropower dam with a fish ladder), also on the Concord River in Lowell. Blueback herring Alewife American shad American eel Sea lamprey Species targeted for restoration include both species of river herring (blueback herring and alewife), American shad, American eel, and sea lamprey, all of which are diadromous fish that depend upon passage between marine and freshwater habitats to complete their life cycle. Reasons The impact of diadromous fish species extends for pursuing fish passage restoration in the far beyond the scope of a single restoration Concord River watershed include the importance and historical presence of the project, as they have a broad migratory range target species, the connectivity of and along the Atlantic coast and benefit commercial significant potential habitat within the and recreational fisheries of other species. -

Methuen Report.Pdf

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS METHUEN MUNICIPAL VULNERABILITY PREPAREDNESS COMMUNITY RESILIENCE BUILDING JUNE 2019 CITY OF METHUEN With assistance from Merrimack Valley Planning Commission & Horsley Witten Group 1 Table of Contents Executive Order 569 and the Massachusetts Municipal Vulnerability Preparedness Program ......................................................................................................................3 Planning Project Vision Statement ..............................................................................5 Climate Data for Methuen and the Shawsheen Basin .................................................7 Methuen Demographics .............................................................................................9 Top Hazards for Methuen ......................................................................................... 11 Concerns & Challenges Presented by Hazards and Climate Change ........................... 14 Methuen Infrastructure & Critical Facilities – Vulnerabilities Identified .................... 14 Methuen Societal Features – Vulnerabilities Identified ............................................. 17 Methuen Environmental Features – Vulnerabilities Identified .................................. 19 Community Strengths & Assets ................................................................................. 21 Top Recommendations for a More Resilient Methuen .............................................. 24 Appendices .............................................................................................................. -

TWO RIVERS MASTER PLAN a Recreational Trail Through the City

BROCKTON TWO RIVERS MASTER PLAN A Recreational Trail through the City CITY OF BROCKTON | Mayor James E. Harrington | City Planner Nancy Stack Savoie Hubert Murray Architect + Planner | July 2008 2 Introduction 0 Program Goals / Common Issues 0 Strategies for Action 07 Area Analyses and Proposals 19 Study Area 01 20 Study Area 02 26 Study Area 0 4 Study Area 04 44 Study Area 05 46 Implementation 48 References 52 Appendix | Maps and Aerials 54 TABLE OF CONTENTS MASTER PLAN OVERVIEW For a quick understanding of the Two Rivers Master Plan, read the Introduction (p.1) and Program Goals / Common Issues (p.3). Strategies for Action (pp.7-17) gives an overview of what needs to be done. Area Analyses and Proposals (pp. 19-47) goes into more detail. Implementation (p.48) indicates next steps and funding possibilities. 20 miles radius from Brockton 5.44 miles E-W HOLBROOK ABINGTON AVON STOUGHTON WHITMAN 5.8 miles N-S EASTON EAST BRIDGEWATER WEST BRIDGEWATER William L. Douglas, shoe manufacturer and retailer, was elected governor of the Commonwealth for the term 905-906. INTRODUCTION Purpose On the other hand, city government has managed to urban parks have been created in the center of The purpose of this study is to provide an overview attract a number of government offices to provide the city as the beginnings of an urban open space of the recreational and environmental potential for local employment as well as attracting federal and system known as the Salisbury Greenway. Frederick restoring and enhancing the urban environment state investment programs in housing, education and Douglass Way (formerly High Street) has been through which Brockton’s Two Rivers run. -

City of Lawrence 2004 Open Space Plan

CITY OF LAWRENCE 2004 OPEN SPACE PLAN Michael J. Sullivan, Mayor Prepared by the City of Lawrence Office of Planning and Development and Groundwork Lawrence City of Lawrence 2004 Open Space Plan CITY OF LAWRENCE 2004 OPEN SPACE PLAN Table of Contents Section 1: Executive Summary 5 Section 2: Introduction 9 A. Statement of Purpose B. Planning Process and Public Participation Section 3: Community Setting 11 A. Regional Context B. History of the Community C. Population Characteristics D. Growth and Development Patterns Section 4: Environmental Inventory and Analysis 17 A. Geology, Soil and Topology B. Landscape Character C. Water Resources D. Vegetation E. Fisheries and Wildlife F. Scenic Resources and Unique Environments G. Environmental Challenges Section 5: Inventory of Lands of Conservation and Recreation Interest 25 A. Private Parcels B. Public and Non-Profit Parcels Section 6: Community Vision 29 A. Description of Process B. Statement of Open Space and Recreation Goals Section 7: Analysis of Needs 31 1 City of Lawrence 2004 Open Space Plan A. Summary of Resource Protection Needs B. Summary of Community’s Needs C. Management Needs, Potential Changes of Use Section 8: Goals and Objectives 39 Section 9: Five-Year Action Plan 42 Section 10: Public Comments 48 Section 11: References 49 Attachment A: Maps Open Space Improvements Since 1997 Regional Context Land Use Lawrence Census Tracts Lawrence Voting Wards Zoning Districts Recreational and Conservation Areas Population Density Density of Children Ages 0-5 Density of Children Ages 6-15 -

Firefighter Statue Debuts in Dudley

Free by request to residents of Webster, Dudley and the Oxfords SEND YOUR NEWS AND PICS TO [email protected] Friday, June 26, 2020 Firefighter statue Dudley voters debuts in Dudley approve budget BY JASON BLEAU enterprise funds. The uses in their projects, CORRESPONDENT budget was considered essentially allowing for a conservative spending residential-only develop- DUDLEY – More than plan taking into account ments on a case-by-case 90 Dudley voters turned the current circumstanc- basis. Applicants would out for the town’s 2020 es under the COVID-19 need approval from the spring annual town meet- pandemic and received Board of Selectmen and ing on Monday, June no vocal opposition from Planning Board to affirm 22, where the proposed voters making it one of such a waiver under the 2021 fiscal year budget the easiest votes of the bylaw changes. received overwhelming night. The proposal had vot- support but a proposal A more controversial ers split down the mid- to amend a zoning bylaw subject however came dle with some seeing it as pertaining to the mill immediately after the an opportunity to loosen conversion overlay dis- budget vote as residents restrictions to allow for trict proved to be more were asked whether or a wider range of uses for divisive topic. not to approve an amend- the mill while others felt Residents voted 72-18 ment to the zoning bylaw it was being proposed to approve a $21,081,882 for the mill conversion specifically to satisfy town budget that includes overlay district to allow one company, Camden $8,863,480 in the gener- for developers of the prop- Partners, who are plan- al fund and $9,895,971 erties within the district ning the redevelopment in education spending. -

Water Quality

LAWRENCE HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT LIHI APPLICATION ATTACHMENT B WATER QUALITY 314 CMR 4.00: DIVISION OF WATER POLLUTION CONTROL 4.06: continued 314 CMR 4.00 : DIVISION OF WATER POLLUTION CONTROL 4.06: continued TABLE 20 MERRIMACK RIVER BASIN BOUNDARY MILE POINT CLASS QUALIFIERS Merrimack River State line to Pawtucket Dam 49.8 - 40.6 B Warm Water Treated Water Supply CSO Pawtucket Dam to Essex Dam, 40.6 - 29.0 B Warm Water Lawrence Treated Water Supply CSO Essex Dam, Lawrence to 29.0 - 21.9 B Warm Water Little River, Haverhill CSO Little River, Haverhill to 21.9 - 0.0 SB Shellfishing Atlantic Ocean CSO The Basin in the Merrimack River - SA Shellfishing Estuary, Newbury and Newburyport Stony Brook Entire Length 10.3 - 0.0 B Warm Water Beaver Brook State line to confluence 4.2 - 0.0 B Cold Water with Merrimack River Spicket River State line to confluence 6.4 -0.0 B Warm Water with Merrimack River Little River State line to confluence with 4.3 - 0.0 B Warm Water Merrimack River Cobbler Brook Entire Length 3.7 - 0.0 B Cold Water Powwow River Outlet Lake Gardner to tidal 6.4 - 1.3 B Warm Water portion Tidal portion 1.3 - 0.0 SB Shellfishing Plum Island River North of High Sandy sand bar SA Shellfishing Outstanding Resource Water 1 Water quality standards for Class B and Class SB waters Designated Use/Standard Parameter Support ≥ 5.0 mg/l Inland waters, Class B, Dissolved Oxygen ≥ 60% saturation unless background conditions warm water fishery lower Massachusetts waters, MADEP Temperature ≤ 28.3ºC (83ºF) pH 6.0 to 8.3 S.U. -

Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Vol. 57, No. 2 Massachusetts Archaeological Society

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Journals and Campus Publications Society Fall 1996 Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Vol. 57, No. 2 Massachusetts Archaeological Society Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/bmas Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Copyright © 1996 Massachusetts Archaeological Society This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. BULLETIN OF THE MASSACHUSETTS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY VOLUME 57 (2) FALL 1996 CONTENTS: Maugua the Bear in Northeastern Indian Mythology and Archaeology . Michael A. Volmar 37 A Cache of Middle Archaic Ground Stone Tools from Lawrence, Massachusetts . James W. Bradley 46 Sunconewhew: "Phillip's Brother" ? . Terence G. Byrne and Kathryn Fairbanks 50 An Archaeological Landscape in Narragansett, Rhode Island: Point Judith Upper Pond . Alan Leveillee and Burr Harrison 58 Indigenous Peoples' Control over and Contribution to Archaeology in the United States of America: Some Issues Shirley Blancke and John Peters Slow Turtle 64 Assistant Editor's Note 68 Brief Note on Submissions 45 Contributors 68 THE MASSACHUSETTS ARCHAEOWGICAL SOCIETY, Inc. P.O.Box 700, Middleborough, Massachusetts 02346 MASSACHUSETTS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Officers: Curtiss Hoffman, 58 Hilldale Rd., Ashland, MA 01721 President Betsy McGrath, 89 Standish Ave., Plymouth, MA 02360 ...................... .. Vice President Thomas Doyle, P.O. Box 1708, North Eastham, MA 02651 Clerk Irma Blinderman, 31 Buckley Rd., Worcester, MA 01602 Treasurer Ruth Warfield, 13 Lee St., Worcester, MA 01602 Museum Coordinator, Past President Elizabeth Little, 37 Conant Rd., Lincoln, MA 01773 Bulletin Editor Lesley H. Sage, 33 West Rd., 2B, Orleans, MA 02653 .................. -

City of Lawrence Capital Improvement Plan (CIP) (FY2018-FY2022)

City of Lawrence Capital Improvement Plan (CIP) (FY2018-FY2022) Lawrence Capital Improvement Plan (FY2018-FY2022) 1 May 2017 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 CIP Overview ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 About the City of Lawrence ..................................................................................................................................... 5 City Facilities .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Lawrence Municipal Airport ............................................................................................................................ 6 Information Technology .................................................................................................................................. 6 Parks and Open Space ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Roadways and Sidewalks................................................................................................................................. 8 School Facilities .............................................................................................................................................. -

Zoning By-Law (PDF)

ZONING BY-LAW of the TOWN OF CLINTON Re-Codified by Town Meeting June 18, 2001 with Amendments to June 4, 2018 TOWN OF CLINTON ZONING BY-LAW Re-Codified by Town Meeting on June 18, 2001 With Amendments to June 4, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1000. PURPOSE AND 3300. HOME OCCUPATIONS AUTHORITY 3310. Home Occupation - As of Right 1100. PURPOSE 3320. Home Occupation - By Special Permit 1200. AUTHORITY 3400. ACCESSORY APARTMENTS 1300. SCOPE 3410. Purpose 1400. APPLICABILITY 3420. Procedure 1500. AMENDMENTS 3430. Conditions 1600. SEPARABILITY 3440. Decision 3500. [RESERVED] SECTION 2000. DISTRICTS 3600. NONCONFORMING USES AND STRUCTURES 2100. ESTABLISHMENT 3610. Applicability 2200. OVERLAY DISTRICTS 3620. Nonconforming Uses 2300. MAP 3630. Nonconforming Structures 2310. Rules for Interpretation of Zoning District Boundaries 3640. Variance Required 2320. Amendment 3650. Nonconforming Single and Two Family Residential Structures 3660. Abandonment or Non-Use SECTION 3000. USE REGULATIONS 3670. Reconstruction after Catastrophe or 3100. PRINCIPAL USES Demolition 3110. Symbols 3680. Reversion to Nonconformity 3120. If Classified Under More than One Use 3700. Temporary Moratorium on Medical Marijuana 3130. Table of Use Regulations Treatment Centers (repealed) 3200. ACCESSORY USES 3750. Temporary Moratorium on Marijuana Establishments and the Sale or Distribution of 3210. Permitted Accessory Uses in All Districts Marijuana and Marijuana Products (repealed) 3220. Nonresidential Accessory Uses 3800. Temporary Moratorium on Multi-Family 3230. Residential Accessory Uses Dwelling Units 3240. Prohibited Accessory Uses 3.2 B Existing Lots (2019) TOWN OF CLINTON ZONING BY-LAW TABLE OF CONTENTS i SECTION 4000. DIMENSIONAL 5330. Temporary Signs REGULATIONS 5340. Off-Premises Signs 4100. GENERAL 5350. Signs in the R1 or R2 District 4110. -

Staff Report

TOWN OF SMITHFIELD, RHODE ISLAND PUBLIC HEARING NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that the Smithfield Town Council will hold a virtual Public Hearing on Tuesday, April 20, 2021 at 6:00 PM. The purpose of the Public Hearing is to consider and obtain public input on a proposed amendment to the Housing chapter of the Comprehensive Community Plan. This amendment is proposed in accordance with the provisions of Section 45-22.2-8 of the General Laws of Rhode Island. VIRTUAL MEETING* Please join the meeting from your computer, tablet or smartphone. https://www.gotomeet.me/RandyRossi/smithfield-towncouncil You can also dial in using your phone. United States (Toll Free): 1 877 568 4106 United States: +1 (646) 749-3129 Access Code: 342-830-965 For technical support dial: 401-233-1010 *Provided, however, that the meeting is allowed to be held virtually. If virtual meetings are prohibited on this date, then the Town Council may convene the meeting at the Smithfield Town Hall, 2nd Floor, Crepeau Hall, 64 Farnum Pike, Smithfield, RI, pursuant to compliance with the latest Executive Order dealing with public meetings. Comprehensive Plan Amendment Summary: The proposed amendment involves a complete rewrite of the Housing section including the Introduction; Data and Trends Snapshot; Types of Housing Development; Housing Costs; Housing Trends; Special Needs; Housing Problems and Needs; Zoning for Residential Uses; Smithfield’s Housing Agencies and Programs; Rehabilitation of Existing Building Stock for Residential Purposes; Low-Moderate Income Housing Data and Trends; Low and Moderate Income Housing Strategies, including the removal of Table H-25 which lists selected properties for LMI housing development; Implementing the Strategies; Goals, Policies; and, Actions; and, Implementation. -

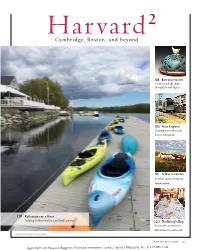

Cambridge, Boston, and Beyond

Harvard2 Cambridge, Boston, and beyond 12B Extracurriculars Events on and off campus through July and August 12D New England Contemporary takes at the Boston Athenaeum 12L A Day in Lincoln A stylish, rural retreat from urban hubbub 12F Reflections on a River Paddling the Merrimack in Lowell and Lawrence 12O The Eating Is Easy Restaurants nestled in the Massachusetts countryside HARVARD MAGAZINE/ NELL PORTER BROWN Harvard Magazine 12a Reprinted from Harvard Magazine. For more information, contact Harvard Magazine, Inc. at 617-495-5746 HARVARD SQUARED Ceramics Program www.ofa.fas.harvard.edu Extracurriculars The “(It’s) All About the Atmosphere Invitational Exhibition,” curated by in- Events on and off campus during July and August structor Crystal Ribich, features a range of objects and celebrates a long tradition of SEASONAL meats, produce, breads and pastries, ceramicists gathering to fire their works The Farmers’ Market at Harvard herbs, pasta, chocolates, and cheeses— together. (June 17-August 19) www.dining.harvard.edu/food-literacy- along with guest chefs and cooking dem- project/farmers-market-harvard onstrations. Science Center Plaza. Swingin’ on the Charles Established in 2005, the market offers fish, (Tuesdays, through November 21) www.swinginonthecharles.blogspot.com Celebrate the tenth anniversary of this From left: Frank Stella’s Star of Persia II (1967), at the Addison Gallery of American Art; from “(It’s) All About the Atmosphere Invitational Exhibition,” Harvard Ceramics lively evening event. Lessons for newbies Program; a Japanese N o- theater costume (1800-1850), at RISD start at 7 P.M.; dancers of any age and abil- FRANKFROM © 2017 LEFT: STELLA / ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/COURTESY OF THE ADDISON GALLERY OF AMERICAN ART; COURTESY OF THE HARVARD CERAMICS PROGRAM/HARVARD OFFICE OF THE ARTS; COURTESY OF RISD One might be tempted to describe Harvard alumnus Dr.