Curriculum, Instruction, Objectives, and Assessment Martin Kozloff

1. A curriculum is two things: a. All of the knowledge you teach and that students are supposed to learn. What students are supposed to learn is defined by objectives---sometimes called standards or goals or benchmarks. A curriculum also consists of: b. The sequence or order of the knowledge taught in the curriculum.

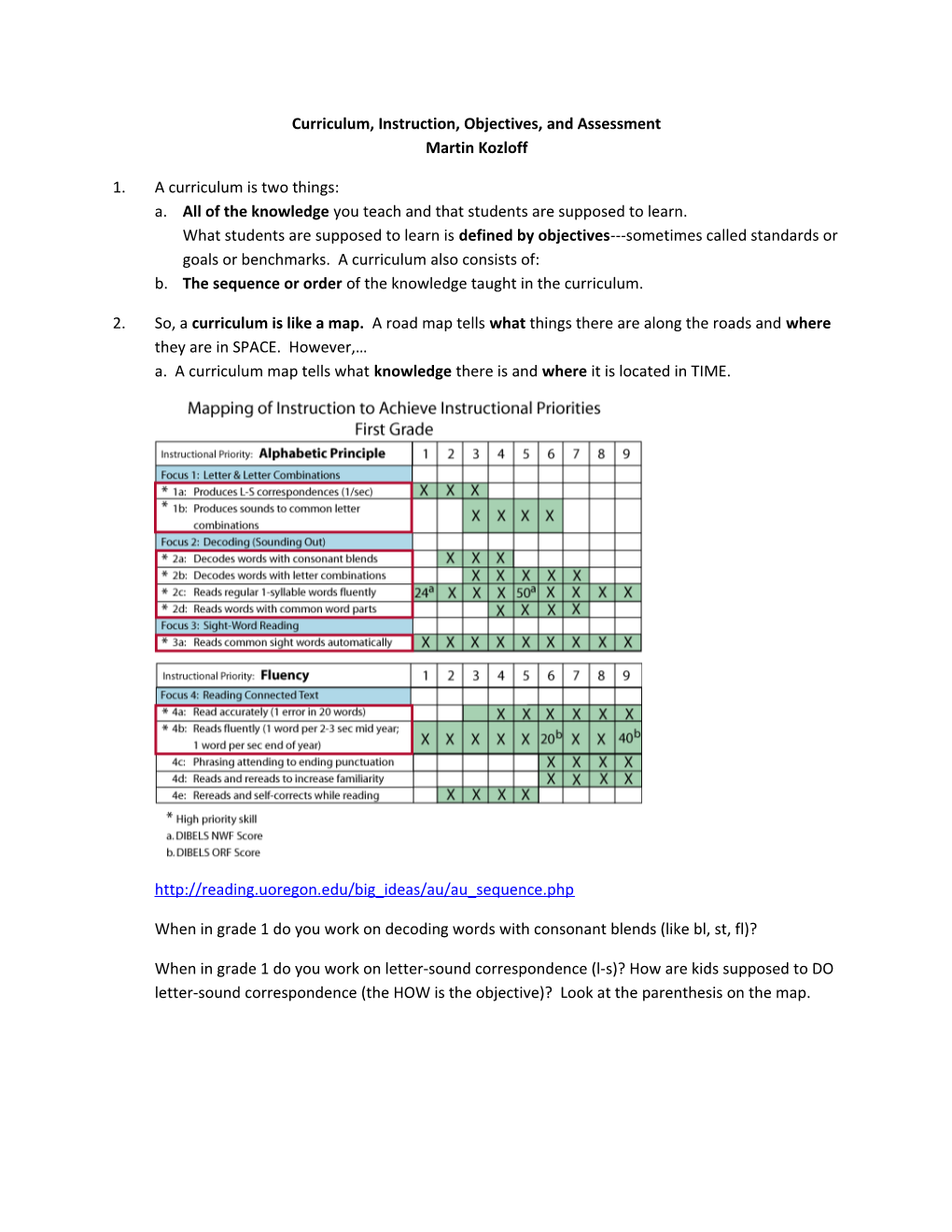

2. So, a curriculum is like a map. A road map tells what things there are along the roads and where they are in SPACE. However,… a. A curriculum map tells what knowledge there is and where it is located in TIME.

http://reading.uoregon.edu/big_ideas/au/au_sequence.php

When in grade 1 do you work on decoding words with consonant blends (like bl, st, fl)?

When in grade 1 do you work on letter-sound correspondence (l-s)? How are kids supposed to DO letter-sound correspondence (the HOW is the objective)? Look at the parenthesis on the map. http://reading.uoregon.edu/big_ideas/comp/comp_sequence.php

More here. http://reading.uoregon.edu/big_ideas/

Another way to represent a curriculum is a scope and sequence chart. http://www.duvalschools.org/static/students/student_software/Parent%20Scope/Destination %20Reading%20Course%20I%20-%20Parent%20Scope.pdf http://www.schools.utah.gov/curr/lang_art/elem/core/core.htm b. But a map doesn’t tell you where to start, where to go next, and where to end. Well, what does tell you where to start, where to go next, and where to end a curriculum map or scope and sequence chart? The answer is,… Objectives tell you where to start, where to go next, and where to end. Objectives tell you what students are supposed to know after each task in a lesson, each lesson in a thematic unit, each thematic unit in a course or strand, each grade level, each school level (such as middle school), and at the end of the whole pre-k-12 sequence. c. But how do you know if students learned what the objectives (benchmarks) say that they are supposed to learn? Answer: You assess (measure in some way) what students have learned when time is up---for example (1) The 1-5 minute task (on definitions such as colony and monarchy) is over. (2) The 30 minute lesson (on the Stamp Act, Sugar Act, Intolerable Acts, Boston Massacre, and Sons of Liberty) is over. (3) The 2-week thematic unit on the American Revolution is over. (4) The semester course or strand (e.g., 5th grade history) is over. (5) The whole grade level (5th grade) is over. (6) Elementary school is over. (7) Middle school is over. (8) High school is over. (9) Pre-k-12 is over.

Many persons say that this is too much testing! They are right---IF the testing is state end of course and end of grade tests. Most assessment can be done with the curriculum materials you are using!! Do you need a state test to tell you if kids can do long division? NO! Just make up a mastery test for long division using examples that you already taught as well as new examples to test generalization of knowledge. These mastery tests are called curriculum based measures.

Why do you have to test after every task, lesson, thematic unit, course, grade level, or school level? Answer. For the same reason that you look at your odometer to see if you are making proper progress. For the same reason that you use a GPS to track you and to tell you if you are on or off course to your destination.

It’s common sense that what students learn and don’t learn in smaller units will affect what students learn in the larger units. For example, if a student doesn’t learn what is necessary in Task 1 of Lesson 1, then the students may not learn what is in Task 2, may not learn the objectives for the lesson and therefore not learn the objectives for the thematic unit, and so on. This is called cumulative dysfluency. So, you have to keep track (monitor progress) to make sure you don’t end up in a ditch.

3. Assessment information at the end of any chunk of curriculum/instruction (task, lesson, thematic unit, strand in a course, etc.) tells you several things that you can use to evaluate curriculum, instruction, and your students’ needs. a. Did the curriculum cover all the skills needed to DO the objectives. For example, if the assessment of the terminal performance includes objectives regarding text comprehension, we would ask if the curriculum in fact taught comprehension routines.

[Look at lessons at the end of 100 Easy Lessons. Did earlier lessons teach kids routines for answering comprehension questions?] b. Is the curriculum sequence logical--so that throughout the sequence students are taught the pre-skills (knowledge elements) needed to learn the next thing in the sequence?

[Pick any complex skill in 100 Easy Lessons. Do a knowledge analysis of this skill. No gio backwards. Do earlier lessons teach all of the elementary knowledge needed to learn the new, more complex skill?]

c. Did instruction (communication) teach the needed knowledge? Did teachers use effective procedures? Table for Assessing and Improving Instruction

Assessing and Improving Instruction

d. If the answer to questions in a, b, and c, above, are Yes, and if some kids are did not meet the objectives, then logically the curriculum and instruction must be adapted for these kids. Maybe they need more practice before they go on to any next lesson. Maybe they need additional scaffolding, such as highlighting. Maybe they need skills taught in even smaller steps.

4. Unless you clearly and concretely define your objective---“Arrive in Boulder, Colorado, before noon on the 18th of May”---you won’t know IF you got there and if you met the objective. Likewise, state instructional objectives so that they are: a. Clear. That is, the words POINT right at something. The words tell exactly what you will see. b. Concrete. That is, the words tell what students will DO. Words like “understand,” “demonstrate,” appreciate,” and “know” are NOT clear and do NOT tell what students will do. However, words like the following ARE clear and concrete. “When the teacher says the name of a concept (democracy, constitutional republic, monarchy, oligarchy) students accurately state the definition, including the genus and difference. For example, ‘Monarchy is a political system (genus) in which one person rules, usually based on heredity or tradition (difference between monarchy as a political system, and other political systems).’”

[Look at the objectives or standards in 2a, above. Are they so clear and concrete that you know exactly how to assess kids and exactly what and how to teach? If not, what do you have to do?]

5. Similar kinds of knowledge (sometimes called content or subject matter) are the strands in a curriculum. For example, language and literacy, math, physical sciences, social sciences.

6. The sequence of knowledge worked on in a strand should be logical. For example, a. Elements of complex skills (sometimes called pre-skills) should be taught before the complex skill is presented. You can’t expect students to comprehend text if they don’t know what the words mean. You can’t expect students to learn the routine for long division if they do not know estimation (25 goes into 64 how many times), multiplication, subtraction, and writing numbers. When should you teach these elements? The answer is: BEFORE you teach the new skills that INVOLVES these elements. And you should review and firm up these PRE- SKILLS when you start lessons on the new skill.

Pre-teach -> review and firm -> review and firm -> review and firm -> Now teach new skill

b. Note that complex skills (containing several elementary skills) are themselves elements of even more complex skills. For example, sounding out a word (rrruuunnn) consists of elements such as saying sounds, saying the right sound that goes with each letter, and reading from left to right. However, sounding out words is itself one recurring element of the more complex skill of reading word lists and sentences; reading sentences is part of the more complex skill of reading paragraphs.

c. Also, a curriculum should first work on knowledge items that are used more often than items that are used less often (teach students to read am, sit, and run, before you teach apex, catharsis, and apoplexy).

How do you find out what the elements of a complex skill are? You do a knowledge analysis. Knowledge Analysis

Assessment of Knowledge of Knowledge Analysis

7. A curriculum should integrate knowledge in two places: a. Within a strand. As said, elements should be combined into wholes. For example, first a strand would teach about rhyme and meter, symbolism, figures of speech, and how certain kinds of poetry occur in certain social conditions. Then the curriculum would teach students to integrate and USE these ELEMENTS in a more complex ROUTINE for analyzing poetry.

b. Across strands. For example, students should use knowledge of math to analyze data from the social science strand---figuring out the slope of the relationship between tax rate (e.g., percentage of income taxed) and revenue from taxes.

See below. What are the strands? Are the objectives clear and concrete? Is the sequence logical: elements complex skills that consist of the elements?

NC Curriculum: Standard Course of Study

California Curriculum

Texas Curriculum

Curriculum Standards

Assessment of Knowledge of Curriculum Standards Instructional Objectives

Assessment of Knowledge of Instructional Objectives

8. Again, chunks or segments or units of curriculum (what you teach and in what order) and instruction (how you deliver the curriculum by interacting with students) come in different sizes. Each larger chunk consists of an arrangement of smaller chunks. For example: a. Your whole life. What are the major periods in your life? What are the main strands (kinds of knowledge you work on) in your life? What do you want to know at the END of your life (terminal objectives)? b. Pre-k to 12. c. All of the strands worked on in elementary, or middle school, or high school. d. All of the strands worked on in one grade in elementary, middle, or high school. e. All the knowledge worked on in one course. f. All the knowledge worked on in one thematic unit (a sequence of lessons) in a course (e.g., U.S. Constitution). Thematic Units are usually a sequence of daily lessons that take maybe 10 to 20 minutes. For example, Lesson 1 on the Constitution might consist information on who attended, where and when the Constitution was written, the purpose of the Constitution (e.g., improvement over the Articles of Confederation), and issues that divided delegates. The next lesson would build on the first lesson, and might teach the first articles in the Constitution. g. All the knowledge worked on in one lesson. Each lesson consists of a sequence of tasks. Tasks might take anywhere from a minute to a bit more. For example, Task 1, Lesson 1 on the Constitution might be facts about writing the Constitution (date, place, delegates). Task 2 might be definitions of concepts (constitution, article, clause, congress, president, judicial, taxation, commerce, militia). Task 3 might be issues that divided delegates. (a sequence of tasks---teacher-student interaction, class projects on a thematic unit on the Constitution. Guided Notes Thematic Unit: U.S. Constitution Lesson 1 Background. Task 1. Facts 1. Who 2. Where 3. When Objectives and assessment. (a) Immediate acquisition test. After stating each fact, ask students to restate. (b) After stating and testing all facts, have students list facts about who, where, and when. Students list at least 4 facts from each group.

Task 2. Concepts 1. Constitution 2. Article 3. Clause 4. Congress Objectives and assessment. . (a) Immediate acquisition test. After stating each definition, ask students to restate. (b) After stating and testing all definitions, say a word, ask students for the definition, give new examples and nonexamples, ask students to identify as an example or nonexample, ask “How do you know?” Students give correct definitions, correctly identify 8/10 examples and nonexamples, amd correctly use the definition 8/10 times to answer “How do you know?”

9. Always plan curriculum and instruction by starting at the END. When you (1) design a curriculum (what to teach and in what order), (2) design instruction for teaching the curriculum (e.g., objectives, examples, what you will say, activities you will use), (3) decide which materials to use, and how to improve the materials, and(4) evaluate student learning (which also evaluates curriculum and instruction)----always start with the end. What will students DO and HOW will they do it.

Let say that you plan curriculum and instruction by starting at the end of an entire k-12 curriculum, or school level (e.g., elementary), or grade level (e.g., 5th), or class (e.g., 5th grade math), or thematic unit (e.g., long division in 5th grade math), or lesson (e.g., lesson 3 on long division), or task (e.g., students do some problems independently).

And let’s say that for any of these endings, you specify a terminal performance (What students will do. This is what you assess.) and terminal objectives (that define how students are supposed to DO the terminal performance).

10. But how do you know WHAT should be in the curriculum (at any level) so that students can proficiently DO the terminal performance as defined by terminal objectives? And how do you know the sequence in which to order the knowledge taught that is supposed to lead to all the proficiencies needed to proficiently do the terminal performance?

The answer is knowledge analysis. Almost any knowledge or skill consists of smaller elements. Consider brushing your teeth. It is a routine (sequence of steps). What do you have to know to DO each step? This knowledge is the elements---the skills that are parts of the whole skill of brushing your teeth. Notice that some of the element skills are repeated in different steps; e.g., locating, reaching, grasping. What would happen if a student was not proficient with one of these elements? The student could not do the steps that REQUIRE these elements. Therefore, the student could not proficiently DO the terminal performance of independently brushing her teeth.

Again, notice that even the elementary skills or knowledge consist of even SMALLER—more elementary skills. For instance, the elementary skill of reaching (for tooth brush, tooth paste, or faucet) is a sequence of smaller elements such as looking and identifying.

Use knowledge analysis to find out the elements of (knowledge needed to proficiently do) a terminal performance from the whole k-12 curriculum down to a simple task in a lesson. Knowledge Analysis

Assessment of Knowledge of Knowledge Analysis

Form for Doing Knowledge Analysis

[Examine the last story in 100 Easy Lessons, math, and Declaration of Independence. Think of objectives, a terminal performance, and how you might assess performance relative to the objectives. Remember: generalization, fluency, retention objectives.]

11. Objectives tell you where you are going---where you are supposed to end up, the knowledge students are to acquire, apply, and retain. But to get students started in a curriculum, you have to locate them on the map or in the score and sequence. What background knowledge do they have and not have?

If you know where students have started (the knowledge they have and the knowledge they don’t have relevant to the new knowledge they are to acquire), then you can plan the curriculum (what to teach and in what order) and instruction (how to group students, where to start in the curriculum, what materials to use, and how to communicate). In other words, you can chart the course of instruction on a curriculum map.

Also, if you know where students started and know where they are supposed to end up, you can plan ongoing assessment, or progress monitoring. In other words, you can tell if students are on course. If so, you keep going. If not, you revise the curriculum (maybe teach additional skills students don’t have) and instruction (maybe give even more practice on each thing you teach). 12. Here’s what the three kinds of assessments look like.

a. Start c. Terminal performance (e.g., read a passage). Evaluate terminal performance in relation to terminal objectives. Measure retention, fluency (accuracy and speed), generalization to new examples, and integration/application (e.g. essay, story reading and comprehension).

Ongoing assessment (progress monitoring) with, for example, standardized or curriculum based mastery tests of acquisition, generalization, fluency, and retention examples every five-ten lessons. 1. Delayed acquisition test with a set examples that were used to teach new knowledge. 2. Generalization set examples = new examples to which students apply knowledge from the acquisition phase of instruction. 3. Fluency set of examples = acquisition and generalization set examples used to build speed and automaticity. 4. Retention set examples = sample from everything taught, to build retention.

Starting (pre, or baseline) assessment. Sample skills from throughout the curriculum to see where students’ skill “top out”---that is, they start struggling, or can’t do it. So, back up a little in the sequence and start there. For example, a student can read everything up to lesson 20 but then starts making errors. So, review and firm lessons 1-14 and start at 15.

Use this starting assessment to: a. Place students IN the curriculum sequence. b. Determine if they need remedial instruction (acceleration to catch up) in certain skills. c. Group students whose knowledge puts them at a similar place (fast group, average group, remedial group). d. Select materials needed (e.g., on vocabulary). e. Select instructional methods (e.g., some students need highly scaffolding instruction). Pre-k Elementary Middle High School K 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 (1)

Language and Literacy ______(5)______(4)______(3)______(2)

Physical science ______

Social science ______

Math ______

(6) Grade four

Grade 4 math course in pre-k-12 curriculum strand

Days/Lessons |___|___|_|______|___|_|__|_____|___|_|_._._._|___|___|___|____|_|__|___|_|_|__|__|____|(6)

(7) Unit on 2-digit multiplication in grade four math

Lesson 1 in Unit on 2-digit multiplication

|______|_____|______|______|(8)|

Task 1 (9) Task 2 Task 3 Task 4

(1) Strands of similar subject matter, or content, arranged as courses.

(2) Terminal performance, defined by terminal objectives for pre-k-12 curriculum. Assessment of pre-k-12 curriculum: (a) Comprehensive test within strands (math) and across strands/courses (use math to analyze historical data). (b) Paper on history of federalism and anti- federalism. (c) Empirical research project integrating math and social science theory and data. (d) Translation of passages in foreign language. (e) Analysis of historical and contemporary documents (e.g., speeches, legislation). (3) Terminal performance, defined by terminal objectives for middle school curriculum. Assessment of middle school curriculum: (a) Comprehensive test within and across strands/courses. (b) Paper on history of North Carolina. (c) Paper on Revolutionary America. (d) Empirical research project integrating math and biology. (e ) Translation of passages in foreign language.

(4) Terminal performance, defined by terminal objectives for elementary school curriculum. Assessment of elementary school curriculum: (a) Comprehensive test within and across strands/courses. (b) Paper on biographies of famous persons and histories of organizations. (c) Empirical research involving observation: qualitative and quantitative data. (d)…

(5) Terminal performance, defined by terminal objectives for pre-k and k curriculum. Assessment pre-k, k curriculum: Comprehensive tests of language, reading, common knowledge, math, social skills, personal skills (attention, motor, etc.). Data are used to place students in first grade classes for fast and prepared vs. slower and/or unprepared students. E.g., starting placement in curriculum/materials; kind of instruction needed (more vs. less explicit and scaffolded).

(6) Terminal performance, defined by terminal objectives for all courses/strands in a particular grade (e.g., grade 4). Assessment of grade- level curriculum: (a) Comprehensive test within and across strands/courses (math, physical science, etc.), measuring retention, fluency, and generalization. (b)…

(7) Terminal performance, defined by terminal objectives for a particular Unit within a course; e.g., multiplication of 2-digit numbers. Assessment of unit: (a) Comprehensive exam that samples earlier-taught problems (test of retention) and new problems (test of generalization), accuracy and speed (fluency).

(8) Terminal performance, defined by terminal objectives for a lesson within a unit. Assessment of lesson: (a) Test sample of acquisition set items (examples) used to teach new knowledge; (b) Test sample of generalization items (examples).

(9) Terminal performance, defined by terminal objectives for a task within a lesson. Assessment of task: (a) Depending on phase of learning worked on in the task, test a sample of items (examples) of acquisition, generalization, fluency, or retention.

O --teach---assess Show pathways

Start progress end/terminal

NC Curriculum: Standard Course of Study

California Curiculum

Texas Curriculum

Curriculum Standards

Assessment of Knowledge of Curriculum Standards

Knowledge Analysis

Assessment of Knowledge of Knowledge Analysis

Form for Doing Knowledge Analysis

Instructional Objectives

Assessment of Knowledge of Instructional Objectives

Phases of Mastery

Phases of Mastery Table

Assessment of Knowledge of Phases of Mastery

Example of Mastery Tests/Checkouts for 100 Easy Lessons . Lessons 1-10

Blank template for Mastery Tests/Checkouts for 100 Easy Lessons

Example of Working on all four phases/mastery test

Lessons