Land Management Plan for the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests Apache, Coconino, Greenlee, and Navajo Counties, Arizona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Geomorphology and Alluvial History of Matzhiwin Creek, a Small Tributary of the Red Deer River in Southern Alberta

(3x mm awmsraais UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA RELEASE FORM NAME OF AUTHOR: Mark Barling TITLE OF THESIS: The geomorphology and alluvial history of Matzhiwin Creek, a small tributary of the Red Deer River in southern Alberta. DEGREE: Master of Science YEAR THIS DEGREE PRESENTED: Fall 1995 Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Library to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis, and except as hereinbefore provided neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatever without the author's prior written permission. UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA The geomorphology and alluvial history of Matzhiwin Creek, a small tributary of the Red Deer River in southern Alberta. By Mark Bariing A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science. Department of Geography Edmonton, Alberta Fall 1995 UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND RESEARCH The undersigned certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research for acceptance, a thesis entitled THE GEOMORPHOLOGY AND ALLUVIAL HISTORY OF MATZHIWIN CREEK, A SMALL TRIBUTARY OF THE . RED DEER RIVER IN SOUTHERN ALBERTA submitted by MARK BARLING in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE. Abstract This study examines the postglacial alluvial chronologies of some of the rivers and creeks in central and southern Alberta. -

Henderson Street Names A

Henderson Street Names STREET NAMEP* FIRE SAM NUMBERING ADDRESS LOCATION MAP MAP STARTS/ENDS A Abbeystone Circle 3728-94 86 Mystical / 360’ CDS 2484-2495 Sunridge Lot 21 Abbington Street 3328-43 77 Courtland / Muirfield 300-381 Pardee GV South Abby Avenue 3231-64 120 Dunbar / Sheffield 1604-1622 Camarlo Park Aberdeen Lane 3229-23 102 Albermarle / Kilmaron 2513-2525 Highland Park Abetone Avenue 4226-16 422 CDS/Cingoli Inspirada Pod 3-1 Phase 2 Abilene Street (Private 3637-94, 260 Waterloo / Mission / San 901-910 Desert Highlands; Blk Mt Ranch within Blk Mtn Ranch) 3737-14 Bruno Ability Point Court 3533-48 169 Integrity Point / 231-234 Blk Mt Vistas Parcel C Unit 3 Abracadabra Avenue 3637-39 259 Hocus Pocus / Houdini 1168-1196 Magic View Ests Phs 2 Abundance Ridge Street 3533-46/56 169 Solitude Point / Value 210-299 Blk Mt Vistas Parcel C Unit 2, 3 Ridge Acadia Parkway 3332-92 143 Bear Brook/American Acadia Phase I Pacific Acadia Place 3329-63 99 Silver Springs / Big Bend No #’s Parkside Village Acapulco Street 3638-42 270 DeAnza / Encanto 2005-2077 Villa Hermosa Accelerando Way 3236-85 233 Barcarolle/Fortissimo Cadence Village Phase 1-G4 Ackerman Lane 3329-16 100 Magnolia / CDS 400-435 The Vineyards Acorn Way 3427-52 54 Wigwam / Pine Nut No #’s Oak Forest Acoustic Street 3537-29 257 Canlite / Decidedly 1148-1176 The Downs Unit 3 Adagietto Drive 3828- 87, 88 Moresca / Reunion 1361-1399 Coventry Homes @ Anthem 3, 4 66/56/46 Adagio Street 3728-11 85 Anchorgate / Day Canyon 801-813 Sunridge Lot 18 Adams Run Court 3735-63 218 155' CDS -

Download Index

First Edition, Index revised Sept. 23, 2010 Populated Places~Sitios Poblados~Lieux Peuplés 1—24 Landmarks~Lugares de Interés~Points d’Intérêt 25—31 Native American Reservations~Reservas de Indios Americanos~Réserves d’Indiens d’Améreque 31—32 Universities~Universidades~Universités 32—33 Intercontinental Airports~Aeropuertos Intercontinentales~Aéroports Intercontinentaux 33 State High Points~Puntos Mas Altos de Estados~Les Plus Haut Points de l’État 33—34 Regions~Regiones~Régions 34 Land and Water~Tierra y Agua~Terre et Eau 34—40 POPULATED PLACES~SITIOS POBLADOS~LIEUX PEUPLÉS A Adrian, MI 23-G Albany, NY 29-F Alice, TX 16-N Afton, WY 10-F Albany, OR 4-E Aliquippa, PA 25-G Abbeville, LA 19-M Agua Prieta, Mex Albany, TX 16-K Allakaket, AK 9-N Abbeville, SC 24-J 11-L Albemarle, NC 25-J Allendale, SC 25-K Abbotsford, Can 4-C Ahoskie, NC 27-I Albert Lea, MN 19-F Allende, Mex 15-M Aberdeen, MD 27-H Aiken, SC 25-K Alberton, MT 8-D Allentown, PA 28-G Aberdeen, MS 21-K Ainsworth, NE 16-F Albertville, AL 22-J Alliance, NE 14-F Aberdeen, SD 16-E Airdrie, Can 8,9-B Albia, IA 19-G Alliance, OH 25-G Aberdeen, WA 4-D Aitkin, MN 19-D Albion, MI 23-F Alma, AR 18-J Abernathy, TX 15-K Ajo, AZ 9-K Albion, NE 16,17-G Alma, Can 30-C Abilene, KS 17-H Akhiok, AK 9-P ALBUQUERQUE, Alma, MI 23-F Abilene, TX 16-K Akiak, AK 8-O NM 12-J Alma, NE 16-G Abingdon, IL 20-G Akron, CO 14-G Aldama, Mex 13-M Alpena, MI 24-E Abingdon, VA Akron, OH 25-G Aledo, IL 20-G Alpharetta, GA 23-J 24,25-I Akutan, AK 7-P Aleknagik, AK 8-O Alpine Jct, WY 10-F Abiquiu, NM 12-I Alabaster, -

Download Date 01/10/2021 04:58:13

University of Saskatchewan Radiocarbon Dates VIII Item Type Article; text Authors Rutherford, A. A.; Wittenberg, J.; Wilmeth, R. Citation Rutherford, A. A., Wittenberg, J., & Wilmeth, R. (1979). University of Saskatchewan radiocarbon dates VIII. Radiocarbon, 21(1), 48-94. DOI 10.1017/S0033822200004215 Publisher American Journal of Science Journal Radiocarbon Rights Copyright © The American Journal of Science Download date 01/10/2021 04:58:13 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/652551 [RADIocAR1 oN, Voi.. 21, No. 1, 1979, P. 48.94] UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN RADIOCARBON DATES VIII A A RUTHERFORD, j WITTENBERG and R WILMETH National Museums of Canada and Saskatchewan Research Council Radiocarbon Dating Laboratory 30 Campus Drive, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan This series reports some of the measurements made since publication of the previous list. Methods essentially remain as described in Saskatch- ewan II (R, 1960, v 2, p 73). The laboratory now joins operation with the National Museum of Canada, Ottawa. The prime purpose is to pro- vide radiocarbon dating service for Canadian archaeologists through the National Museum, although commercial services are available to others as analytical capacity permits. SAMPLE DESCRIPTIONS I. GFoLOGIc SAMPLES Scrimbit series, Saskatchewan Wood from buried forest, 3.6 to 5.2m below surface in glacial kettle, J Scrimbit farm near Kayville (49° 46' N, 105° 11' W). Found in layer of gyttja (Dew, 1959). Coil and subm 1958 by B A McCorquodale, Sask Mus Nat Hist, Regina (now Prov MUS Alberta, Edmonton). S-80. 11,500 ±300 10cm diam conifer trunk in horizontal orientation 3.9m below sur- face. -

European Patent Bulletin 1997/33

Europäisches European Office européen Patentamt Patent Office des brevets Europäisches Patentblatt European Patent Bulletin Bulletin européen des brevets i — 13.08.1997 0 788 301 - 0 789 508 1997 33 Herausgeber und Schriftleitung Published and edited by Publication et rédaction Europäisches Patentamt European Patent Office Office européen des brevets Direktion 5.4.2 Directorate 5.4.2 Direction 5.4.2 Schottenfeldgasse 29 Schottenfeldgasse 29 Schottenfeldgasse 29 Postfach 82 P.O. Box 82 BP 82 A-1072 Wien A-1072 Vienna A-1072 Vienne • Bezugsbedingungen Conditions of Sale Conditions de vente Abonnement Subscription Abonnement Abonnementpreis pro Jahrgang: Subscription price p.a.: Prix de l'abonnement annuel: DEM 790,- DEM 790 790 DEM Versandkosten: Postage: Frais d'envoi: DEM 490,— (Europa) DEM 490 (Europe) 490 DEM (Europe) DEM 860,— (Übersee) DEM 860 (overseas) 860 DEM (outre-mer) Einzelverkauf: Price per issue: Vente au numéro: DEM 25,— (excl. Versandkosten) DEM 25 (excl. postage) 25 DEM (Frais d'envoi non compris) • Bestellungen sind zu richten an: • Orders should be sent to: • Les commandes doivent être adressées à: Europäisches Patentamt European Patent Office Office européen des brevets EPIDOS EPIDOS EPIDOS Hauptdirektion Patentinformation Principal Directorate Patent Information Direction Principale Informations Brevets Schottenfeldgasse 29 Schottenfeldgasse 29 Schottenfeldgasse 29 A-1072 Wien A-1072 Vienna A-1072 Vienne Tel. Int.: 43.1.521.26.0 Tel. Int.: 43.1.521.26.0 Tél. Int.: 43.1.521.26.0 Fax Int.: 43.1.52126.2495 Fax Int.: 43.1.52126.2495 Fax Int.: 43.1.52126.2495 Zahlungsmöglichkeiten siehe dritte Um- Details of how to effect payment are given on the Les détails concernant les modalités de paiement schlagseite. -

Geologic Framework and Glaciation of the Central Area Christopher L

Boise State University ScholarWorks Anthropology Faculty Publications and Department of Anthropology Presentations 1-1-2006 Geologic Framework and Glaciation of the Central Area Christopher L. Hill Boise State University This document was originally published in Handbook of North American Indians. Geological Framework and Glaciation of the Central Area CHRISTOPHER L. HILL During the Late Pleistocene, the Laurentide ice sheet correlation. Starting in the 1950s chronometric techniques, extended over the western interior Plains and Great chiefly radiocarbon dating, were applied to test the devel Lakes region in the central region of North America. This oping framework. This led to the abandonment and reor central area generally encompasses the northwestern inte ganization of much of the earlier terminology (Willman rior Plains of North America, extending from the Rocky and Frye 1970). For example, the Iowan, Tazewell, Cary, Mountains in the west to the western Great Lakes and and Mankato Wisconsin glaciations were all placed into Hudson Bay in the east (figs. 1-2). It includes parts of the the Woodfordian. The Woodfordian substage is followed Mackenzie River, Missouri River, and Mississpippi River systems. Deglaciation of this region led to the development of landscapes that were inhabited by Rancholabrean faunal communities including human groups. Three major ice centers formed in North America: the Labrador, Keewatin, and Cordilleran. The Cordilleran covered the region from the Pacific Ocean to the eastern front of the Rocky Mountains ("Geological Framework and Glaciation of the Western Area," this vo!.) while the Labrador and Keewatin ice fields combined to form the Laurentide Ice Sheet. The glacial geology of the central region of North America includes evidence of the lobes and sublobes of the Keewatin ice as well as lobes from the Labrador ice source that expanded from the Lake Superior and Lake Michigan basins. -

University of Alberta Landslide Incidence and Its Relationship With

University of Alberta Landslide incidence and its relationship with climate in three river valleys in the Bearpaw Formation in southern Alberta BY Linheng Liang A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences Edmonton, Alberta Spring 1999 National Library Biblioth6que nationale 1+B of,",, du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Your Me Votra rBfdrmue Our file Notre rtilBrmce The author has granted a nono L'autem a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pennettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, preter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la fonne de microfiche/fih, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format Bectronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui prothge cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent &e imphes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract Landslide incidences on the Battle, Red Deer, and Bow Rivers were mapped in the Bearpaw Forrnation in southern Alberta, and the incidences on north- and south- facing slopes of the three river valleys were mapped as well. -

Mapping and Detecting Change in the Aeolian Sand Deposits of Southem Alberta Using Wet Year-Dry Year Landsat Thematic Mapper Imagery

University of Alberta Mapping and Detecting Change in the Aeolian Sand Deposits of Southem Alberta Using Wet Year-Dry Year Landsat Thematic Mapper Imagery Melodie Lynne Sept @ A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences Edmonton, Alberta Fall, 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale (*Iof Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distriiute or seIl reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic fomats. la fome de microfiche/fihn, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be p~tedor otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Landsat Thematic Mapper imagery acquired for a wet and dry year were wdto map and detect change in aeolian s~iddep6sits of southern Alberta Post-classification cornparison between the two years showed that both image sets discriminated between the various deposits, but with differences in their extent. -

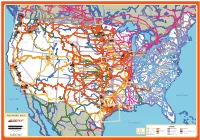

BNSF Network

!( Dauphin Williams Lake Lake CP CN !( CP CN CN CN Matane CP TRR CN !( Hardisty CN !( Exeter CTRW WRI CN CBC2 CN !( CN CTRW CN CWRL CP Moosonee uma !( CN CN Red Deer !( CN CN CP Chibouga Mont-Joli Campbellton CN !( CN !( Matapédia!( Chasm CP CN !( Lime !( APXX CP !( BRITISH COLUMBIA !( Clinton CP Pavilion CP Saskatoon !( Beresford NBEC !( !( !( Wakely CN CN Golden Elstow !( CN !( CP !( !( CP Swan River !( Dolbeau Lillooet CP Guernsey Preeceville !( !( !( Sturgis CN Pemberton CN !( !( !( Kamloops CP !( CN CN Brunswick Mines !( Creekside !( !( CP Allan Lanigan Wadena CANADA !( Mons Sicamous Rosetown RS !( Strongfield CP u-Loup Whistler !( ONT CN !( CN CN !( CN !( !( Rivière-d CN !( Watrous !( Kamsack !( !( !( Matagami MadawaskaEdmundston Cochrane !( Lyalta Oyen !( Canora !( !( Swift CN Amazon Nokomis Grevet !( !( !( Conquest !( Saint-André Van Buren Calgary !( CN CN !( St. Leonard !( CN Chambord !( NEW BRUNSWICK Armstrong CP BSR !( Squamish BSR CN !( !( Vernon !( CP !( CN !( !( Laporte Davidson CP !( !( SVI CN !( CP Clermont CP SASKATCHEWAN Yorkton Lumby !( Bassano Eston LMR !( MANITOBA !( Nakina MNR CN McGivney GSR CN Odell !( High River !( Dauphin CN Vancouver !( Stout !( !( Bulyea !( North Vancouver ALBERTA CP !( !( Bredenbury Hearst !( McNeill !( Kyle CN Melville CN Fort Kent New Westminster CP !( !( Beechy ONT CRC Brownsville CN Tilbury !( Fording CP !( !(!( Surrey !( CN Saint-François Fredericton !( !( !( Cochrane !( La Sarre CN !( !( CP Pine Falls !( Longlac !( \! Yarbo Winnipeg Beach !( !( Barraute!( Senneterre CP Wickett SVI " -

CHANGE in Soutaeastern ALBERTA, CANADA

UNVERSITY OF ALBERTA POSTGLACIAL GEOMORPHK RESPONSE AND ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE IN SOUTaEASTERN ALBERTA, CANADA CELINA CAMPBELL A THESIS SüBMITTED TO TEE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND RESEARCH IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPW DEPARTMENT OF EARTH AND ATMOSPHERIC SCIENCES EDMONTOK, ALBERTA SPRING, 1997 The author bas granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une ficenct non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibiiothèque nationale du Crmada de reprduce, loan, distribute or seli reprodube,preter, distnbuaou copies of hismer thesis by any meam vmdn des copies de sa thèse & and in any form or format, making cpelqye manière et sous quelque this thesis available to interested fome que ce soit pour mettre des persons. exemplaires de cette thèse à la disposition des personnes intéressées- The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in merthesis. Neither &oit d'autcur qui protège sa thèse. Ni the thesis nor substantial extracts la thèse ni âes extraits substantieis de fiom it may be p~tedor othenivise celle-ci ne doivent être imprimes ou reproduced with the author's autrem~ptreproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT This thests tests the hypothesis that the tempo and pattern of geomorphic changes in southeastem Alberta over the postglacial pend reflects the nature and intensity of climatic forcing as expresseci principally through hydroIogica1 response. In order to test this hypotbesis, five separate midies were conducteà in different geomorphic settings to investigate a wide range of dominant geomorphic proceaesses which operated through the varying climates of the postglacial pend This first Chapter intmduces the study and study area, and develops an opriori empiricai mode1 through a synthesis of published and unpublished calibrated radiocarbon dates of postglacial geomorphic events from southeastem Alberta and smunding plains. -

Liberty County Obituaries

FLORENCE MAE (HASSETT) AA~ERG born: Jun. 22. 1 898 -- died: Mar. 30. 1 996 Liberty County Times Apr. 3. 1996 Florence had been a hard worker her entire life. She officially retired at age 80. Because of her good health, she was fortunate to lead an active and independent life in her post retirement years. during this time she made many solo road trips to California to escape the Montana winters. Florence was a longtime member of Ou~ Savior's Lutheran Church in Chester and did the janitorial work the're fo'r many years. she enjoyed vegetable gardening, embroidery, reading, and playing cards (she ~as especially fond of pinochle andwhlst). She collected cups and saucers. Her family will always remember her skills as a good cook and homemaker. Florence Aaberg Florence is survived by two Wednesday at the Mountainview daughters, Mrs. Dave (Coral) Fyall of Florence Mae (Hassett) Aaberg was Cemetery in Shelby by Pastor Kalispell and Mrs. (Gus (Annabelle) born at Nekoma, North Dakota on Haugestuen. Funeral arrangements Fransen of Shelby; one sister, Gladys June 22nd, 1898. She was ?ne of four are by Rockman Chapel of Chester. Rustan of Williston, North Dakota; one children born to David and Mathilda Memorials will be given to the Toole brother, Jim Hassett of Devils Lake, (Ford) Hassett. She grew up in North County Nursing Home in Shelby or Dakota and received her formal North Dakota; 13 grandchildren; 25 Our Savior'S Lutheran Church in great-grandchildren; 6 great-great education at Nekoma. Florence began Chester. working in a cook-car for a thrashing grandchildren; and numerous crew at age 12. -

Truckstop City State Product Retail Cost Spread FLYING J FUEL STOP

01/13/2020 / ALBERTA REPORT / EARLY-BIRD EDITION Truckstop City State Product Retail Cost Spread FLYING J FUEL STOP #813 Airdrie AB B5SMEU 3.8257 3.2117 0.6140 ULS 3.8257 3.2103 0.6154 PETRO-CANADA Aldersyde AB B5SMEU 3.3616 3.2125 0.1491 ULS 3.3616 3.2111 0.1506 EMMES ESSO Bassano AB B5SMEU 3.1673 3.2033 -.0360 ULS 3.1673 3.2018 -.0345 PETRO-CANADA Bonnyville AB B5SMEU 3.2746 3.1156 0.1591 ULS 3.2746 3.1141 0.1605 FLYING J #792 Brooks AB B5SMEU 3.7387 3.2508 0.4879 ULS 3.7387 3.2493 0.4894 FLYING J #848- ROAD KING TRUCK Calgary AB B5SMEU 3.6517 3.1973 0.4543 ULS 3.6517 3.1959 0.4558 FLYING J TRAVEL PLAZA #793 Calgary AB B5SMEU 3.8257 3.2024 0.6233 ULS 3.8257 3.2010 0.6247 FLYING J CARDLOCK #814 Calgary AB B5SMEU 3.8257 3.2056 0.6201 ULS 3.8257 3.2042 0.6215 FLYING J TRAVEL PLAZA #785 Calgary AB B5SMEU 3.8257 3.2024 0.6233 ULS 3.8257 3.2010 0.6247 FLYING J #850 Edmonton AB B5SMEU 3.7097 3.1105 0.5992 ULS 3.7097 3.1090 0.6007 PETRO-CANADA Edmonton AB B5SMEU 3.0136* 3.1031 -.0895 ULS 3.0136* 3.1017 -.0881 PETRO-CANADA Edmonton AB B5SMEU 3.2456 3.1142 0.1314 ULS 3.2456 3.1127 0.1329 FLYING J CARDLOCK #818 Edson AB B5SMEU 3.8547 3.1586 0.6961 ULS 3.8547 3.1571 0.6976 FLYING J #819 Fort Mcmurray AB B5SMEU 3.8547 3.2865 0.5682 ULS 3.8547 3.2850 0.5697 PETRO-CANADA Fort Mcmurray AB ULS 3.1586 3.1927 -.0341 PETRO-CANADA Fort Mcmurray AB ULS 3.1586 3.1927 -.0341 PETRO-CANADA Fort Saskatchewan AB B5SMEU 3.2456 3.1142 0.1314 ULS 3.2456 3.1127 0.1329 PETRO-CANADA Fox Creek AB B5SMEU 3.0716 3.1059 -.0343 ULS 3.0716 3.1044 -.0328 FLYING J CARDLOCK