“I'm Rare As Affordable Health Care...Or Going to Wealth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter Edition VOLUME 6 ISSUE 3

Mise en Scéne Winter Edition VOLUME 6 ISSUE 3 CSUEB Spellers take the stage in Inside this Issue "The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee" Director, Marc Jacobs, shares his thoughts on this musical comedy Upcoming Shows 2 My first encounter with "The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee" was with the Post Street Theatre in San Francisco, 10 years ago. This was the first Our Students 3 production after the original Broadway cast, and I had several friends in the show, which was cast locally. One of the cast members was James Monroe Checking In 4 Iglehart (CSUEB Graduate) who had been in previous musicals I had directed in San Jose. James has since gone on to win the Tony Award as the Genie in Disney’s Broadway production of "Aladdin." James was playing 'Comfort Guest Artists 5 Counselor' Mitch Mahoney in "Spelling Bee," and his performance was so perfect that the producers decided to model every subsequent 'Mitch' on James’ performance. Another friend in the show was Aaron Albano, who had Featured Faculty 7 started out as one of the teenagers in my production of The Music Man that I directed in San Jose, and has since gone on to appear on Broadway in The Wiz, Newsies, and currently in Allegiance. The San Francisco company of Information 9 "Spelling Bee" was so successful, that the producers ultimately used those actors to replace the Broadway company once the original actors were ready to leave the show. One of those original actors, Sarah Salzburg ‒ the original “Schwarzy” in ‘Spelling Bee - was the daughter of a good friend of mine. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Revising the Rags-To-Riches Model: Female Famine Immigrants in New York and Their Remarkable Saving Habits

REVISING THE RAGS-TO-RICHES MODEL: FEMALE MASTER FAMINE IMMIGRANTS IN NEW YORK AND THEIR THESIS REMARKABLE SAVING HABITS Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, “Emigrant Savings Bank Interior with design”, July, 1882 Melanie Strating 4836561 Master Thesis Historical Studies (HLCS) First Supervisor: dr. M.C.M. Corporaal Second Supervisor: Prof. dr. J. Kok 3 October 2018 Word Count: 34.866 1 Summary The rags-to-riches paradigm has played an important role in describing immigrant experience in nineteenth-century America and focuses on the immigrant‟s development from poverty to wealth. Due to a conflation of Irish famine and immigrant historiography, Irish immigrants appeared at the bottom of every list of immigrant development: they were seen as the most impoverished immigrants America has ever welcomed. Women, moreover, have often been overlooked in research. In 1995 bank records, from the Emigrants Industrial Savings Bank became publically available. A large proportion of these bank records were owned by Irish immigrants and a significant percentage of account holders were women. This thesis focuses on Irishwomen who moved to New York during the Great Irish Famine and its immediate aftermath. Records from the EISB show that some of these women were able to save considerable sums of money. By combining the bank records of domestic servants, needle traders and business owners, with analyses of working women in historical novels written by the famine generation and newspaper articles, this interdisciplinary thesis aims to give Irish female immigrants a voice in historical research. This thesis enlarges our knowledge about famine immigration and shows us how Irishwomen can enrich our understanding about female economic activity and women on the nineteenth-century job market. -

Pacnet Number 23 May 6, 2010

Pacific Forum CSIS Honolulu, Hawaii PacNet Number 23 May 6, 2010 Philippine Elections 2010: Simple Change or True problem is his loss of credibility stemming from his ouster as Reform? by Virginia Watson the country’s president in 2001 on charges of corruption. Virginia Watson [[email protected]] is an associate Survey results for vice president mirror the presidential professor at the Asia Pacific Center for Security Studies in race. Aquino’s running mate, Sen. Manuel Roxas, Jr. has Honolulu. pulled ahead with 37 percent. Sen. Loren Legarda, in her second attempt at the vice presidency, dropped to the third On May 10, over 50 million Filipinos are projected to cast spot garnering 20 percent, identical to the results of the their votes to elect the 15th president of the Philippines, a Nacionalista Party’s presidential candidate, Villar. Estrada’s position held for the past nine years by Gloria Macapagal- running mate, former Makati City Mayor Jejomar “Jojo” Arroyo. Until recently, survey results indicated Senators Binay, has surged past Legarda and he is now in second place Benigno Aquino III of the Liberal Party and Manuel Villar, Jr. with 28 percent supporting his candidacy. of the Nacionalista Party were in a tight contest, but two weeks from the elections, ex-president and movie star Joseph One issue that looms large is whether any of the top three Estrada, of the Pwersa ng Masang Pilipino, gained ground to contenders represents a new kind of politics and governance reach a statistical tie with Villar for second place. distinct from Macapagal-Arroyo, whose administration has been marked by corruption scandals and human rights abuses Currently on top is “Noynoy” Aquino, his strong showing while leaving the country in a state of increasing poverty – the during the campaign primarily attributed to the wave of public worst among countries in Southeast Asia according to the sympathy following the death of his mother President Corazon World Bank. -

2020 Latin American and Latinx Studies Symposium Panels Panel

1 2020 Latin American and Latinx Studies Symposium Panels Panel: Environment and Culture in Latin America ° Religión y Naturaleza: la Creación del ambiente en la película La Luz Silenciosa, Mariana Gutierrez Suarez, Southwestern University** La creación audiovisual del ambiente y el desarrollo de la historia se manifiestan en la utilización de dos componentes importantes: la naturaleza y la religión. La religión forma la parte social de los personajes mientras que la naturaleza expresa sus emociones individuales. A través del paisaje natural que cambia con las estaciones del año al igual que cambian los protagonistas, los preceptos de la religión, en cambio, se manifiestan rígidos y difíciles de concordar con las acciones humanas. Este contraste nos muestra la importancia de reconocer la organicidad de la naturaleza con el hombre, y de seguir las leyes de conducta y convivencia en nuestros conflictos con nosotros mismos y con los demás, y las maneras de solucionarlos. ° A Threat to Brazilian Biodiversity and Climate Change: The Soy Industry, Beatriz Olivieri, Rollins College My presentation discusses the current environmental dilemma Brazil is facing. The desire to pursue significant economic development leads the Brazilian government to make poor decisions regarding the environment. The ongoing deforestation in Brazil related to the growth of soybeans is responsible for affecting important and unique native biomes along with causing the displacement of indigenous people -who are important actors in the protection of the environment-. In the last two decades, the soy expansion in Brazil was equivalent to an area five times the size of Switzerland. With the ArcGIS mapping tool, I was able to show the conflict between land being used for soy production that initially belonged to indigenous groups. -

Doctor Strange Comics As Post-Fantasy

Evolving a Genre: Doctor Strange Comics as Post-Fantasy Jessie L. Rogers Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Karen Swenson, Chair Nancy A. Metz Katrina M. Powell April 15, 2019 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Fantasy, Comics Studies, Postmodernism, Post-Fantasy Copyright 2019, Jessie L. Rogers Evolving a Genre: Doctor Strange Comics as Post-Fantasy Jessie L. Rogers (ABSTRACT) This thesis demonstrates that Doctor Strange comics incorporate established tropes of the fantastic canon while also incorporating postmodern techniques that modernize the genre. Strange’s debut series, Strange Tales, begins this development of stylistic changes, but it still relies heavily on standard uses of the fantastic. The 2015 series, Doctor Strange, builds on the evolution of the fantastic apparent in its predecessor while evidencing an even stronger presence of the postmodern. Such use of postmodern strategies disrupts the suspension of disbelief on which popular fantasy often relies. To show this disruption and its effects, this thesis examines Strange Tales and Doctor Strange (2015) as they relate to the fantastic cornerstones of Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings and Rowling’s Harry Potter series. It begins by defining the genre of fantasy and the tenets of postmodernism, then it combines these definitions to explain the new genre of postmodern fantasy, or post-fantasy, which Doctor Strange comics develop. To show how these comics evolve the fantasy genre through applications of postmodernism, this thesis examines their use of otherworldliness and supernaturalism, as well as their characterization and narrative strategies, examining how these facets subvert our expectations of fantasy texts. -

Tornado Times

MAR 2021 TORNADOmagazine Map to the End of Semester • Follow this map as the end of the year comes increasingly close. EXCLUSIVE Ryan Ebrahamian a Hoover High Story March 2021 Two Sides of the Same Coin 3 by Sebastian Guzman • Read about students' differing opinions on online school. Map to end of semester 5 by Nooneh Gyurjyan • Follow this map as the end of the year comes increasingly close. Editor's List of Most Anticipated Movies of 2021 6 by Sebastian Guzman • Link Crew, a new program at Hoover High School, was created to help freshmen navigate through their first year during a pandemic. 9 a Hoover High Story by Sebastian Guzman • Ryan Ebrahamian, a former Hoover student from the class of 2016 talks about his memories of high school, the importance of heritage, “My Big Fat Armenian Family,” and much more. 14 Grade Nite Canceled by Monet Nadimyan and Melia Movsesian • Magic Mountain announces the cancellation of their 2021 event, months after Disneyland did the same. Michael Jordan's History At Hoover 15 by Cher Pamintuan • Did you know that Michael Jordan and the 1984 USA Olympic basketball team secretly practiced at the Hoover gym? In the world...where are Latinos? 17 by Sebastian Guzman • In the world of politics, music, and film, Latinos are on the rise, proving that Latino voices are essential to our modern-day society. Editor's Note After the warm receival of our first issue, we are excited to release our second issue of the Tornado Magazine. During these past few months, we have been working remotely alongside Hoover’s journalism staff on curating a student-friendly publication. -

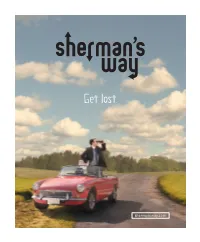

SW Press Booklet PRINT3

STARRY NIGHT ENTERTAINMENT Presents starring JAMES LE GROS (“The Last Winter” “Drugstore Cowboy”) ENRICO COLANTONI (“Just Shoot Me” “Galaxy Quest”) MICHAEL SHULMAN (“Can of Worms” “Little Man Tate”) BROOKE NEVIN (“The Comebacks” “Infestation”) with DONNA MURPHY THOMAS IAN NICHOLAS and LACEY CHABERT (“The Nanny Diaries”) (“American Pie Trilogy”) (“Mean Girls”) edited by CHRISTOPHER GAY cinematography by JOAQUIN SEDILLO written by TOM NANCE directed by CRAIG SAAVEDRA Copyright Sherman’s Way, LLC All Rights Reserved SHERMAN’S WAY Sherman’s Way starts with two strangers forced into a road trip of con - venience only to veer off the path into a quirky exploration of friendship, fatherhood and the annoying task of finding one’s place in the world – a world in which one wrong turn can change your destination. The discord begins when Sherman, (Michael Shulman) a young, uptight Ivy- Leaguer, finds himself stranded on the West Coast with an eccentric stranger and washed-up, middle-aged former athlete Palmer (James Le Gros) in an attempt to make it down to Beverly Hills in time for a career-making internship at a prestigious law firm. The two couldn't be more incompatible. Palmer is a reckless charmer with a zest for life; Sherman is an arrogant snob with a sense of entitlement. Palmer is con - tent reliving his past; Sherman is focused solely on his future. Neither is really living in the present. The only thing this odd couple seems to share is the refusal to accept responsibility for their lives. Director Craig Saavedra brings his witty sensibility into this poignant look at fatherhood and friendship that features indie stalwart James Le Gros in an unapologetic performance that manages to bring undeniable charm to an otherwise abrasive character. -

Marlon Riggs Papers, 1957-1994 M1759

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt8v19s4ch No online items Marlon Riggs Papers, 1957-1994 M1759 Finding aid prepared by Lydia Pappas Department of Special Collections and University Archives Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford, California, 94305-6064 [email protected] 2011-12-05 Marlon Riggs Papers, 1957-1994 M1759 1 M1759 Title: Marlon Riggs Papers Identifier/Call Number: M1759 Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 112.0 Linear feet(37 manuscript boxes, 5 half-boxes, 3 card boxes, 34 flat boxes, 28 cartons, 1 oversize box) Date (inclusive): 1957-1994 Abstract: This collection documents the life and career of the documentary director, Marlon Troy Riggs, 1957-1994. The majority of the materials in the Collection are from the period between 1984 and Riggs' death in 1994, the decade of his concentrated film-making activity, as well as some more personal materials from the late 1970s onwards. The papers include correspondence, manuscripts, subject files, teaching files, project files, research, photographs, audiovisual materials, personal and biographical materials created and compiled by Riggs. General Physical Description note: Audio/Visual material housed in 90 cartons containing: 16 Film reels, 149 VHS videotapes, 437 Umatic videotapes, 602 Betacam videotapes, 50 Digibeta videotapes, I Betamax videotape, 1 D8 tape, 6 micro cassette tapes, 2 DARS tapes, 14 Hi-8 tapes, 10 DAT tapes, 8 reels 2inch video, 27 reels 1inch video, 49 DVDs, 108 audio cassettes, 48 audio reels, 2 compact discs; Computer Media: 1 floppy disc 8inch, 171 floppy discs 5.25inch, 190 3.5-inch floppy discs, and papers housed in 77 boxes, 62 flat boxes, and 11 half boxes. -

Up Announces Two Series Acquisitions

For Immediate Release UP UNVEILS A FRESH SLATE OF 30 UPLIFTING ORIGINALS FOR SECOND HALF OF 2014 AND 2015 New Original and Premiere Movies, Including the Epic Bible Movie Noah A True Inspirational Story Life of a King, Country Music Star Jimmy Wayne’s Paper Angels, Plus 4 New Original Series and More Episodes of the Fan Favorite Series “Heartland” Star Lineup Includes Cuba Gooding, Jr., Dennis Haysbert, LisaGay Hamilton, Mark Salling, Laura Vandervoort, Lacey Chabert, Samaire Armstrong, LeToya Luckett and More ATLANTA – April 8, 2014 – UP, America’s favorite channel for uplifting family entertainment, today unveiled a compelling original programming slate, including 30 new original and premiere movies and four series for the second half of 2014 and 2015. Now in its 10th year, UP is projected to reach 73 million households in 2015 and is the leading destination for fresh, contemporary, uplifting family-friendly entertainment. UP is presenting exceptional opportunities to advertisers during the 2014-15 upfront on its trademark Upfront Bus, which serves as the network’s mobile venue for client meetings and events. For the second half of 2014, nine original and premiere movies headline UP’s slate for a total of 18 for the year, continuing UP’s promise to viewers that at least one original or premiere movie will air every month. The films star a diverse range of top tier talent, including Mark Salling (“Glee”), Laura Vandervoort (“Smallville”), Lacey Chabert (“Party of Five”), Samaire Armstrong (“Resurrection”) and Grammy®-Award winning singer LeToya Luckett (UP’s “For Richer or Poorer”). For 2015, UP’s slate includes 19 original and premiere movies, headlined by its first original biblical epic Noah. -

LACEA Alive Feb05 7.Qxd

01-48_Alive_March_v6.qxd 2/25/11 5:12 PM Page 33 www.cityemployeesclub.com March 2011 33 Comes Alive! by Hynda Rudd Tales From the City Archives City Archivist (Retired) and Club Member Tom LaBonge and the Hollywood Sign n City Councilman and Club Member Tom LaBonge fought to keep the L.A. icon in public hands. At the ceremony where the Hollywood sign area was saved from developers. Hefner of Playboy Enterprises to close the What has not been known by many of the and largest donors to this effort were Los Photos courtesy the Trust for Public Land. $12.5 million deal to save the Hollywood sign. citizens of this City is that as far back as 1978, Angeles philanthropist Aileen Getty and the At the press conference, it was revealed that the Hollywood sign, as it looks today, came Tiffany & Co. Foundation. “I thank Hugh n advertising billboard on Mt. Lee, in the parcel of land would be preserved and about because Hugh Hefner was the one to Hefner and Aileen Getty for their critical con- “Athe hills overlooking the film capital, annexed to Griffith Park. raise money to rebuild it. As a big fan of the tributions, along with everyone whose gener- [was] erected in 1923. The sign is 50 feet high, Tom LaBonge stated his thanks to the sign, Hefner came forward again in 2010 with ous spirit moved them to join the campaign to 450 feet long, weighs 480,000 pounds, and TPL, the Hollywood Sign Trust and the his $900,000 that brought forth the closing of save one of America’s most famous urban cost $21,000 to construct. -

The Norman Conquest: the Style and Legacy of All in the Family

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Boston University Institutional Repository (OpenBU) Boston University OpenBU http://open.bu.edu Theses & Dissertations Boston University Theses & Dissertations 2016 The Norman conquest: the style and legacy of All in the Family https://hdl.handle.net/2144/17119 Boston University BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION Thesis THE NORMAN CONQUEST: THE STYLE AND LEGACY OF ALL IN THE FAMILY by BAILEY FRANCES LIZOTTE B.A., Emerson College, 2013 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts 2016 © 2016 by BAILEY FRANCES LIZOTTE All rights reserved Approved by First Reader ___________________________________________________ Deborah L. Jaramillo, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Film and Television Second Reader ___________________________________________________ Michael Loman Professor of Television DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Jean Lizotte, Nicholas Clark, and Alvin Delpino. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I’m exceedingly thankful for the guidance and patience of my thesis advisor, Dr. Deborah Jaramillo, whose investment and dedication to this project allowed me to explore a topic close to my heart. I am also grateful for the guidance of my second reader, Michael Loman, whose professional experience and insight proved invaluable to my work. Additionally, I am indebted to all of the professors in the Film and Television Studies program who have facilitated my growth as a viewer and a scholar, especially Ray Carney, Charles Warren, Roy Grundmann, and John Bernstein. Thank you to David Kociemba, whose advice and encouragement has been greatly appreciated throughout this entire process. A special thank you to my fellow graduate students, especially Sarah Crane, Dani Franco, Jess Lajoie, Victoria Quamme, and Sophie Summergrad.