Corporeal Activism in Elizabeth Acevedo's The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Top 200 Most Requested Songs

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2013 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 2 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 3 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 4 Lmfao Sexy And I Know It 5 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 6 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 7 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 8 Psy Gangnam Style 9 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 10 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 11 B-52's Love Shack 12 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 13 Maroon 5 Feat. Christina Aguilera Moves Like Jagger 14 Jepsen, Carly Rae Call Me Maybe 15 V.I.C. Wobble 16 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 17 Beatles Twist And Shout 18 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 19 Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Feat. Wanz Thrift Shop 20 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 21 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 22 Lmfao Feat. Lauren Bennett And Goon Rock Party Rock Anthem 23 Pink Raise Your Glass 24 Outkast Hey Ya! 25 Isley Brothers Shout 26 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 27 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 28 Mars, Bruno Marry You 29 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 30 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 31 Lumineers Ho Hey 32 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 33 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 34 Sister Sledge We Are Family 35 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 36 Temptations My Girl 37 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 38 Train Marry Me 39 Kool & The Gang Celebration 40 Daft Punk Feat. -

View Entire Issue As

Storm Prince@AOL. Manitowoc Co. farm- Handsome, in a James (414) 8706184 [2] com, or send responses boy. Computers inter- Dean way, athlete, bar- to Quest (#50), P.O. net, old cars, travel in ber, butch, wants to hear 37 y.o. CWM 5'10", Box 1961, Green Bay, upper midwest & from real gay men not 195 lbs .„ blfor lkg for VI 54305 Canada, camping & afraid of being physical friendship/relationship. outdoor activities. in a very intense way. Have speech handicap. CWM, 54, 200 lbs., Prefer mederately jhairy Get to know me. Write: Will relocate. Mark average build. Enjoy well-endowed bottom, Charles Yeder, PO Box Schicker, N83W 15776 cuddling, walks in the must be HIV-. No fats, 900-I, Sturtevant, WI Apple Valley' woods, outdoors...Ikg ferns, dniggies or heavy 53177-09cO [2] Menomonee Falls, WI for friendship & maybe drinkers. Smokers OK. 53051. (414) 253-0921. more, Eastern Shawano E-mail: willkapp@net- Very good looking 21- No games [1 ] Co. (rural). Write PO net.net ... or Boxholder, yr.-old seeks a sugar Box 238, Shawano, WI TRY IT FREE! Meet PO 9582, Green Bay, daddy (ies). 5'10", 130 54166 [2] local gayfoi singles by WI 54308-9582. [2] lbs., br. hair, bl. eyes, phone on Milw. hottest ORAL MAJORITY! dating service! Listen to Record, listen, respond 100's of messages from to personals Free! local single men who C o nf i d e n i i a I want to meet you...for Co„„ccfl.o# (414) 224- dating, sex or just con- 5431 -18+ Use free versation. -

View Entire Issue As

AppLETON Eldorado's sTEVENs POINT ADUIT PARH STORES Your one stop source for all Gay-Lesbian-Bisexual, and TV Videos, Magazines, Toys, Lotions, Oils, Lingerie, Books, Games, Novelties, Gifts, CD-ROMS, DVDs, Greedng Cards, Over-the-Hill Gag Gifts, Bachelor and Bachelorette Party Gifts and Invitations, Whips, Cuffs, and Bondage Items and Leather Apparel. SATISFACTION GUARANTEED PLEASE VISIT US SOON SThvENS PORT 3219 CHURCH STREET BUS. 51 SOU" 715-343-9877 Open Thurs., Fir., Sat. 10 an -11 pin speech impediment, but mobile. Lkg for some fun in the Green Bay Backstage Productions Smoker, social drinker, willing to relo- area. (920) 826-2869. Pete [2] cate,. (414) 253-0921 or write Mark GWM 5'6", blond, 220 lbs., 36, seeks Too much of a presents Schicker, N83 W15776 Apple Valley, relationship-minded male 18-44. Menomonee Falls, WI 53051 [2] Closeness, sharing our lives, cuddling, good thing is Your fantasy on film?! (you keep the pasionate sex for hours. Greeks & wonderful! Iidtins encouraged. PO Box 511664, negatives). No restrictions! Milw. cell Milw„ WI 53203-0281 [2] ©u@sO phone (414) 899-4343 [2] ORALLY EXPL.ORE! Tonight on gvIAiss 8a,y Meditterean jock, 29, 5`10",1651bs„ WOW! The Confidenhal Connection! LS+ P.O. Box 1961 very hot, masculine, good-lkg, exotic Entertainment J'_' Record, listen & Respond FREE! Green Bay, looks, well hung, bubble butt, skg a @agea 18+ can (920) 431-9000, ue code 4166 (888) 390-2598 Wisconsin 54305 muscular masculine aggressive top all- American down-to-earth stud, 22-38, Two young Ghana fellas seek penpals: (414) 597-9698 friendly, passionate, into travel, candle- Club 5 -Madison, WI Kwabena Ankomah, Box KF 1799, Parties licht dinners, the gym & exploring the Keforidua ER, Ghana; &Richard © Toll Free Club Shows Sunday -February 21,1999 -9:30pm 1 -COO-578-3785 possibility of a monogamous relation~ Hondah, PO Box 126, Abvekel-Accra, ship. -

Top 200 Most Requested Songs

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2013 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 2 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 3 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 4 Lmfao Sexy And I Know It 5 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 6 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 7 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 8 Psy Gangnam Style 9 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 10 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 11 B-52's Love Shack 12 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 13 Maroon 5 Feat. Christina Aguilera Moves Like Jagger 14 Jepsen, Carly Rae Call Me Maybe 15 V.I.C. Wobble 16 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 17 Beatles Twist And Shout 18 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 19 Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Feat. Wanz Thrift Shop 20 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 21 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 22 Lmfao Feat. Lauren Bennett And Goon Rock Party Rock Anthem 23 Pink Raise Your Glass 24 Outkast Hey Ya! 25 Isley Brothers Shout 26 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 27 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 28 Mars, Bruno Marry You 29 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 30 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 31 Lumineers Ho Hey 32 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 33 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 34 Sister Sledge We Are Family 35 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 36 Temptations My Girl 37 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 38 Train Marry Me 39 Kool & The Gang Celebration 40 Daft Punk Feat. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Chuck Richardson

BlazeVOX 2k7 an online journal of voice Fall 2007 Chuck Richardson 4. Digressions On A Recurring Dream 6,898 words, 4 percent passive, 71 percent reading ease. It is blistering elsewhere, yet not here as two-dozen friends gather poolside. A hazy skyline shimmering a mirage fogs via remote control dreams of glassy, urban sophistication. The illusion resonates pulp, swimming the couple’s trust in a cultivated hereafter. Do you Jonah, take this woman, Linda, to be your lawful wedded wife? A family court judge and ace trombonist is presiding. He’s sixty and serious, calmly leading the couple through the ritual, just as they’d rehearsed it, with the about-to- be newlyweds standing nude on the diving board, hovering over the deep end. Neither can swim, but their naked friends have rehearsed saving them. I do. And do you, Linda, take this man, Jonah, to be your lawful wedded husband? If so, answer I do. She looks over Jonah, realizing she’s given up hope for someone sexier. Expectations duly lowered, she imagines the one who ditched her standing in Jonah’s place. He, for his part, cannot fathom his good fortune. Linda’s much younger than he, more attractive, even sexy once you get to know her. She’s also mysterious. He feels, much to his obvious excitement, that she’s reading him like a book, her eyes perusing every fold, every gray hair, each blemish and scar—from the inside-out through his eyes. Eye-to-eye exposure is plainly titillating him. I do, she answers, at last, having finished the run-on sentence fragment of material phenomena called fiancé, now husband. -

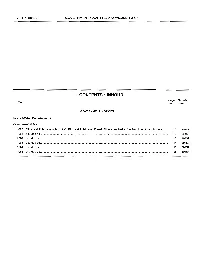

CONTENTS ·Inholld

2 NO.30457 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 9 NOVEMBER 2007 CONTENTS ·INHOLlD No. Page Gazette No. No. GOVERNMENT NOTICES Home Affairs, Department of Government Notice 1060 Films and Publications Act, 1996: Film and Publication Board: Films classified X18 - Restricted to adults only . 3 30457 1061 do.: do.: do . 6 30457 1062 do.: do.: do . 10 30457 1063 do.: do.: do. 14 30457 1064 do.: do.: do . 18 30457 1065 do.: do.: do . 25 30457 STAATSKOERANT, 9 NOVEMBER 2007 No.30457 3 GOVERNMENT NOTICES DEPARTMENT OF HOME AFFAIRS No. 1060 9 November 2007 FILM AND PUBLICATION BOARD FILMS AND PUBLICA TlONS ACT, 1996 The Film and Publication Board has, in terms of section 18(4)(a)(ii) of the Films and Publications Act, 1996, as amended, classified the films listed below X18 - RESTRICTED TO ADULTS ONLY. The films contain scenes ofexplicit sexual conduct and may bedistributed only bya holder of a licence to conduct the business of adult premises, issued by a licensing authority in terms of Item 2(h) of the Business Act, No. 71 of 1991, registered with the Film and Publication Board, subject to the conditions set out in section 24(2) of the Films and ~b~aoo~Act. \ DATE TITLE DISTRIBUTOR 30/04/2007 4 HOURS INTHE HOSPITAL X DDREAM PICTURES 02/05/2007 INNOCENCE CCCC 02/05/2007 BAREBACKING BACKPACKERS CCCC 02/05/2007 RIDING BRUNO CCCC 03/05/2007 PMO # 33: GIRL-GIRL STUDIO # 2 JT WHOLESALE 03/05/2007 KILL JILL JT WHOLESALE 03/05/2007 PLO # 41: DIANA GOLD JT WHOLESALE 03/05/2007 CASTINGS # 50: MIRIAM SHE LOVES SEX JT WHOLESALE 03/05/2007 PBL # 53: WILD WET BITCHES JT WHOLESALE 03/05/2007 PSP # 11: VERTICAL SEX LIMIT JT WHOLESALE 03/05/2007 INTERACTIVE JT WHOLESALE 04/05/2007 MILF FUCKERS VOLUME # 1:MOMMY EATS CUM JT WHOLESALE 04/05/2007 MILF FUCKERS VOLUME # 2: 40FIRST TIME MILFS JT WHOLESALE 04/05/2007 MILF FUCKERS VOLUME # 3: BANGIN' THE MILF NEXT DOOR JT WHOLESALE 04/05/2007 BUMP 'NGRIND PHOENIX XXX DVD 04/05/2007 PUMPS 'NDUMPS PHOENIX XXX DVD 4 No. -

Mediamonkey Filelist

MediaMonkey Filelist Track # Artist Title Length Album Year Genre Rating Bitrate Media # Local 1 Kirk Franklin Just For Me 5:11 2019 Gospel 182 Disk Local 2 Kanye West I Love It (Clean) 2:11 2019 Rap 4 128 Disk Closer To My Local 3 Drake 5:14 2014 Rap 3 128 Dreams (Clean) Disk Nellie Tager Local 4 If I Back It Up 3:49 2018 Soul 3 172 Travis Disk Local 5 Ariana Grande The Way 3:56 The Way 1 2013 RnB 2 190 Disk Drop City Yacht Crickets (Remix Local 6 5:16 T.I. Remix (Intro 2013 Rap 128 Club Intro - Clean) Disk In The Lonely I'm Not the Only Local 7 Sam Smith 3:59 Hour (Deluxe 5 2014 Pop 190 One Disk Version) Block Brochure: In This Thang Local 8 E40 3:09 Welcome to the 16 2012 Rap 128 Breh Disk Soil 1, 2 & 3 They Don't Local 9 Rico Love 4:55 1 2014 Rap 182 Know Disk Return Of The Local 10 Mann 3:34 Buzzin' 2011 Rap 3 128 Macc (Remix) Disk Local 11 Trey Songz Unusal 4:00 Chapter V 2012 RnB 128 Disk Sensual Local 12 Snoop Dogg Seduction 5:07 BlissMix 7 2012 Rap 0 201 Disk (BlissMix) Same Damn Local 13 Future Time (Clean 4:49 Pluto 11 2012 Rap 128 Disk Remix) Sun Come Up Local 14 Glasses Malone 3:20 Beach Cruiser 2011 Rap 128 (Clean) Disk I'm On One We the Best Local 15 DJ Khaled 4:59 2 2011 Rap 5 128 (Clean) Forever Disk Local 16 Tessellated Searchin' 2:29 2017 Jazz 2 173 Disk Rahsaan 6 AM (Clean Local 17 3:29 Bleuphoria 2813 2011 RnB 128 Patterson Remix) Disk I Luh Ya Papi Local 18 Jennifer Lopez 2:57 1 2014 Rap 193 (Remix) Disk Local 19 Mary Mary Go Get It 2:24 Go Get It 1 2012 Gospel 4 128 Disk LOVE? [The Local 20 Jennifer Lopez On the -

Exploring Female Athletes' Body Perceptions

SQUEEZING IN: EXPLORING FEMALE ATHLETES’ BODY PERCEPTIONS Mallory E. Mann A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2015 Committee: Vikki Krane, Advisor Dafina-Lazarus Stewart Graduate Faculty Representative Nancy Spencer Dryw Dworsky ii ABSTRACT Vikki Krane, Advisor Much attention has been paid to female college athlete body image over the last three decades. However, relatively few inquiries employed a holistic approach that examined the myriad of interrelated sociocultural and personal factors influencing athletes’ body perceptions. The primary purpose of the current study was to explore female college athletes’ body image in both social and sport settings. A secondary purpose was to investigate the sociocultural context and how it influenced athletes’ body perceptions. Finally, this study sought to understand the ways in which female athletes’ social identities helped explain their body-related behaviors. Feminist and intersectional methodological approaches guided this inquiry to create partial, in- depth understandings of how female athletes think about and relate to their physiques. The study is particularly unique in its commitment to representing multiple, diverse stories from athletes without privileging one type of body perception. Using an intersectional methodology contextualized athletes body descriptions to uncover deeper meanings and underlying factors. Twenty female college athletes participated in unstructured interviews. These athletes represented eight different varsity sports at NCAA Division I, II, and III institutions. This study offers a new perspective on the relationship between motivational team climate and female athlete body image. While task-oriented team climates still appear to serve as a protective factor against body disturbances among athletes, findings also indicated that a team’s obsession with the body seemed more closely tied to body image issues than a team’s goal orientation. -

Promo Only Country Radiodate

URBAN RADIO ARTIST 05 01 17 OPEN this on your computer. Place your cursor in the “X” Colum. Use the down arrow to move down the cell and place an “X” infront of the song you want played. Forward the file by attachment to [email protected] or F 713-661-2218 X TRK TITLE ARTIST DATE LENGTH BPM STYLE 16 Chill Bill $tone, Rob f./ J. Davi$ & Spooks 11/1/2016 2:58 54 Hip-Hop 16 Chill Bill $tone, Rob f./ J. Davi$ & Spooks 11/1/2016 2:58 54 Hip-Hop JuJu On That Beat (TZ 7 Anthem) & zayion mccall Zay Hilfigerrr 12/1/2016 2:23 80 Hip-Hop JuJu On That Beat (TZ 7 Anthem) & zayion mccall Zay Hilfigerrr 12/1/2016 2:23 80 Hip-Hop 15 Im The Man (Fifty) 50 Cent f./ Sonny Digital 4/1/2016 3:53 98 Hip-Hop 15 Im The Man (Fifty) 50 Cent f./ Sonny Digital 4/1/2016 3:53 98 Hip-Hop 15 Used 2 2 Chainz 13-Nov 3:45 89 Urban 7 Watch Out 2 Chainz 11/1/2015 3:23 65 Hip-Hop 13 I\'m Different 2 Chainz 13-Jan 3:25 97 Hip Hop 12 Riot 2 Chainz 12-May 2:44 65 Hip Hop 22 Gotta Lotta 2 Chainz & Lil Wayne 6/1/2016 3:22 82 Hip-Hop 22 Gotta Lotta 2 Chainz & Lil Wayne 6/1/2016 3:22 82 Hip-Hop 15 Big Amount 2 Chainz f./ Drake 10/1/2016 3:06 67 Hip-Hop 15 Big Amount 2 Chainz f./ Drake 10/1/2016 3:06 67 Hip-Hop 9 Good Drank 2 Chainz f./ Gucci Mane & Quavo 3/1/2017 3:41 66 Hip-Hop 3 No Lie 2 Chainz f./Drake 12-Jul 3:56 65 Urban 9 Netflix 2 Chainz f./Fergie 13-Oct 3:53 62 Rhythm/Urban 2 Feds Watching 2 Chainz f./Pharrell 13-Aug 4:05 70 Rhythm/Urban 15 Milly Rock 2 Milly 2/1/2016 3:39 70 Hip-Hop 15 Milly Rock 2 Milly 2/1/2016 3:39 70 Hip-Hop 10 Milly Rock 2 Milly f./ A$AP -

Breaking Baniers Just a Few Weeks Ago at 33 Remains the Tunes's Praaice to Guard Diseased Pariah News

traguc. Mosi or tnem arc legitmute enterpnsc >oiiau^ s REAL 12bSFWeeklyBMay 1,1991 PETER LAUFER Breaking baniers just a few weeks ago at 33 remains The Tunes's praaice to guard Diseased Pariah News. Not The magazine has a broader appeal the identities of sex crime complain¬ only is the staff of the San than the two thought it would. Sub¬ ants so long as that is possible and Francisco-based quarterly fac¬ scription orders arc coming in from conforms to fair journalistic stan¬ 1itings deadlinea stressfulpressuretimetoatcom¬the across the country and not just from dards." What makes that statement plete issue number three, co-founder AIDS sufferers. Thorne says people silly, and what makes it clear that the and co-editor Tom Shearer just died who are HIV-negative read DPN Times isn't sure what to do about the from AIDS. because "they want to leara what tness it's created, is that Bowman's The magazine, known as DPN, is a others are experiencing. We take on name has suddenly disappeared from sobering humor magazine. "Of, by, serious subjeas with humor and irony the Times' vocabulary. In this "Edi¬ and for and that people with HIV disease," just transforms it." tor's Note" she is again referred to as reads the masthead statement of pur¬ Right now Thorne is looking for a "the woman," even though the of¬ pose. "We arc a forum for infected new business partner to keep DPNgo¬ fending profile from the week before people to share their thoughts, feel¬ ing and for volunteer proofreaders had printed her name 12 times.