Underground Home Designs For some, underground home designs allow them live in harmony with their surroundings and to more easily acknowledge the beauty in nature. By Loretta Hall

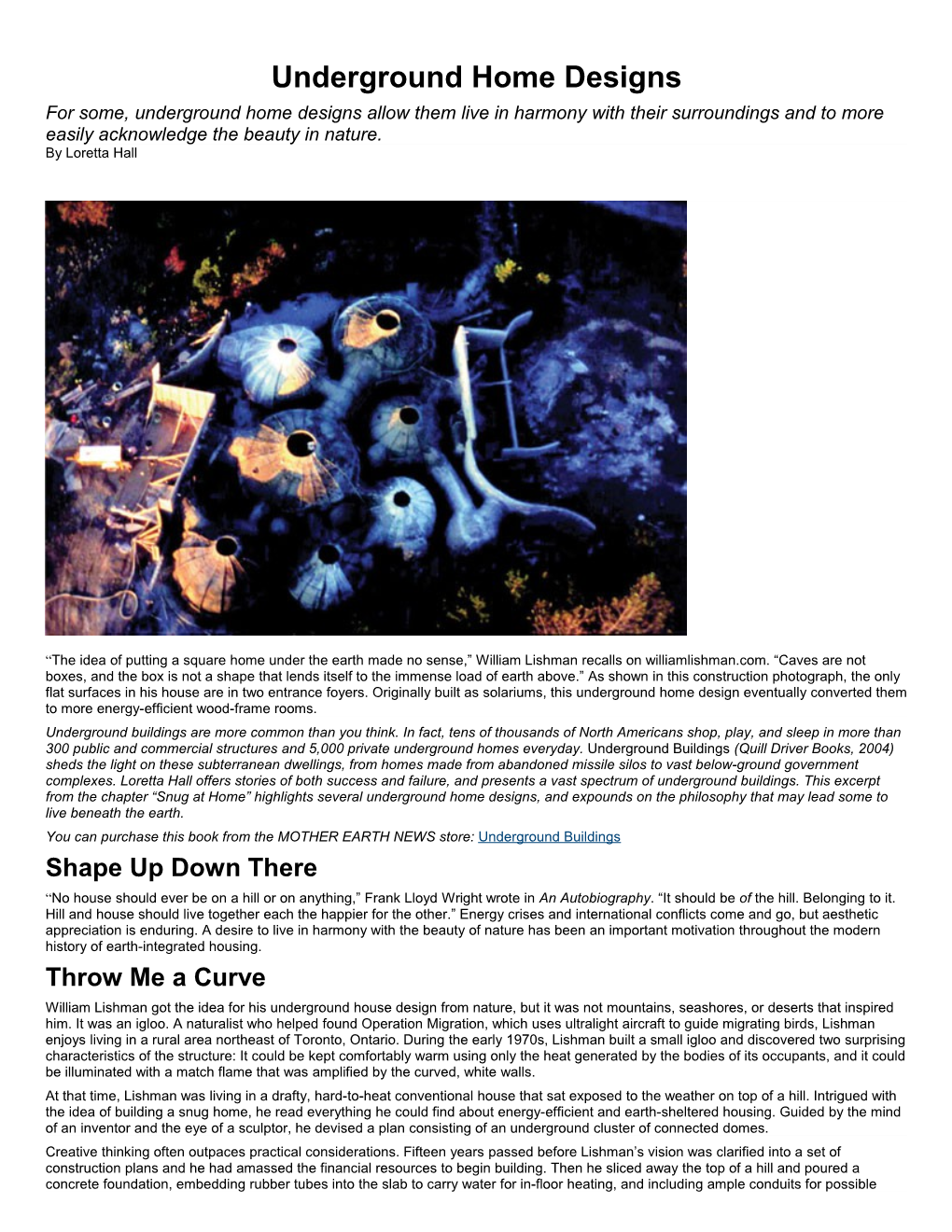

“The idea of putting a square home under the earth made no sense,” William Lishman recalls on williamlishman.com. “Caves are not boxes, and the box is not a shape that lends itself to the immense load of earth above.” As shown in this construction photograph, the only flat surfaces in his house are in two entrance foyers. Originally built as solariums, this underground home design eventually converted them to more energy-efficient wood-frame rooms. Underground buildings are more common than you think. In fact, tens of thousands of North Americans shop, play, and sleep in more than 300 public and commercial structures and 5,000 private underground homes everyday. Underground Buildings (Quill Driver Books, 2004) sheds the light on these subterranean dwellings, from homes made from abandoned missile silos to vast below-ground government complexes. Loretta Hall offers stories of both success and failure, and presents a vast spectrum of underground buildings. This excerpt from the chapter “Snug at Home” highlights several underground home designs, and expounds on the philosophy that may lead some to live beneath the earth. You can purchase this book from the MOTHER EARTH NEWS store: Underground Buildings Shape Up Down There “No house should ever be on a hill or on anything,” Frank Lloyd Wright wrote in An Autobiography. “It should be of the hill. Belonging to it. Hill and house should live together each the happier for the other.” Energy crises and international conflicts come and go, but aesthetic appreciation is enduring. A desire to live in harmony with the beauty of nature has been an important motivation throughout the modern history of earth-integrated housing. Throw Me a Curve William Lishman got the idea for his underground house design from nature, but it was not mountains, seashores, or deserts that inspired him. It was an igloo. A naturalist who helped found Operation Migration, which uses ultralight aircraft to guide migrating birds, Lishman enjoys living in a rural area northeast of Toronto, Ontario. During the early 1970s, Lishman built a small igloo and discovered two surprising characteristics of the structure: It could be kept comfortably warm using only the heat generated by the bodies of its occupants, and it could be illuminated with a match flame that was amplified by the curved, white walls. At that time, Lishman was living in a drafty, hard-to-heat conventional house that sat exposed to the weather on top of a hill. Intrigued with the idea of building a snug home, he read everything he could find about energy-efficient and earth-sheltered housing. Guided by the mind of an inventor and the eye of a sculptor, he devised a plan consisting of an underground cluster of connected domes. Creative thinking often outpaces practical considerations. Fifteen years passed before Lishman’s vision was clarified into a set of construction plans and he had amassed the financial resources to begin building. Then he sliced away the top of a hill and poured a concrete foundation, embedding rubber tubes into the slab to carry water for in-floor heating, and including ample conduits for possible wiring needs in the future. He built steel frames for seven onion-shaped domes, welding a network of rebar between arched vertical trusses. After moving the frames into position on the foundation and linking them together, he covered them with a mesh known as expanded metal lathe. The final construction step was applying gunite. For the last interior layer of gunite, Lishman mixed powdered marble with the concrete to create an attractive wall finish. Modeled after a ferro-concrete technique used for building boats, Lishman’s construction system resulted in a watertight structure. The exterior surface was also treated with multiple layers. First came a waterproofing coat of tar. The next layer, which was thin near the top of the dome and several feet thick near the bottom, consisted of dry sand. A network of tubes was embedded into the sand to circulate air warmed in two solariums attached to the house. The sand layer was covered with a layer of vermiculite insulation and a rubber membrane before adding a final layer of topsoil and seeding it with grass. The interior of Lishman’s curvaceous home is decorated more with form than with images. In fact, he remarks that it is difficult to hang pictures on the nonflat wall surfaces. Rounded cupboards, countertops, and furniture were custom made. Even the door hinges for the unique, truncated ellipse-shaped interior doors had to be hand crafted. Some visitors are distracted by the acoustic characteristics of the hard, curved interior surface, but Lishman himself likes the effect. “With two tiny speakers, I get almost ‘concert hall’ quality music,” he says. Dune Houses Architect William Morgan’s first earth-roofed residential buildings are nearly invisible inside grass-covered dunes on the seashore of Atlantic Beach, Florida. Within the sandy mound nestle two egg-shaped, one-bedroom apartments. On the ocean side, all that is visible is a pair of oval openings that enclose small patios. At the rear of each patio is a glass wall that forms one end of the apartment’s living room. On the landward side of the dune, twin paved walkways curve around a greenery-filled island of soil before joining at a vertical concrete swirl that frames a wood-paneled exterior foyer. The dune itself, which was removed during construction of the apartments, was carefully resculpted to its original contours after the building was completed. Each cozy, 750-square-foot unit is a two-story apartment. The front door is at the loft level, which contains an interior foyer, a bathroom, and an open-ended bedroom that overlooks the living area below. A kitchen and dining area occupy the lower-level space under the loft. The wood of the loft structure and interior stair wall compliment the concrete surfaces of the perimeter walls. One long wall of the apartment curves in an oval arc reminiscent of the dune itself. The other long wall, which separates the apartment from its twin, is straight, offering visual contrast and a flat surface for interior decoration. The design of the dune houses was groundbreaking in two ways. First, it was one of the first subsurface buildings to use the earth cover as a structural element. “We designed the shells in careful balance with the surrounding earth so that the inward pressure of the earth presses uniformly on the shell, locking or post tensioning the gunite shell in place,” Morgan told the authors of Earth Sheltered Housing Design. “The structure actually is stronger because of the earth pressing on it.” Second, the design process employed computer modeling rather than blueprints—an innovative approach in 1974. Even the elliptical shape of the shell was determined by a computer analysis devised to maximize floor space and optimize the load-bearing characteristics of the structure. To turn the computer-generated design into to a physical reality, Morgan and his design engineer came up with a grid-based system. First, a reinforced concrete floor pad was poured, with rebar extending upward from a raised perimeter edge. The builder then used chalk to mark a grid on the surface of the floor. For each intersection point of the grid, a pole was fashioned to represent the desired height of the shell at that spot. Using those guideposts, the builder formed arches of rebar that spanned the oval foundation and created a three- dimensional gridwork. Covering the gridwork with mesh provided an adequate surface onto which a half-inch-thick layer of gunite could be sprayed. After hardening overnight, this shell was sturdy enough to act as a form for a 2-inch-thick layer of concrete that was sprayed onto its interior. The following day, another 2-inch-thick layer of concrete was sprayed onto the exterior surface. Finally, a liquid bituminous waterproofing layer was brushed onto the outside of the shell. The entire process, from excavation to earth covering, was completed in six weeks. An environmentally conscious architect, Morgan designed the dune houses to blend with the natural landscape and preserve the view of their neighbors. Twenty-five years after building them, he reports that the rental units, which he still owns, are never vacant. About the same time that he designed and built the dune houses, he devised an alternative, straight walled version of two- and three-bedroom duplexes to be constructed with concrete block walls and precast concrete panel roofs. Planned for construction in dunes on Amelia Island, Florida, the project was halted by opponents who objected to disturbance of the landscape, even though it would ultimately be reconstructed to its natural profile. Morgan reports that, ironically, dunes in that area were eventually flattened for construction of a golf course community.

I Get the Point In sharp contrast to the flowing curves of his dune houses, William Morgan’s Hilltop House crowns a shallow hill with the crisp lines of a square pyramid. The result is a harmonious and intriguing interplay of geometrically different elements, combining a circular, grass-covered mound with a cap of triangular planes punctuated with rectangular openings. The imaginative design constitutes Morgan’s answer to a client who requested a “why has someone not thought of it before?” house. Built in 1975 near Gainesville, Florida, the house encompasses 3,300 square feet, much of it hidden within the hilltop. Enclosed by grass- covered berms, the main floor consists of three rectangular wings emanating from a central foyer. One wing contains a kitchen and dining room, another holds a study, and the third consists of two bedroom suites. An outdoor patio adjoins each of these rooms, cutting through the hillside to provide abundant window space and exterior doorways. On the fourth side of the central hall, the house’s front door faces an open-air court that leads to a two-car garage embedded in the hill’s southeast face. Above the central portion of the house, a second-story “observatory” room with four windowed walls overlooks the surrounding citrus groves. “It is a building as landscape,” Morgan said of Hilltop House in an April 1978 AIA Journal article. Some twenty-five years later, he is still passionate about the concept of earth-integrated architecture. “I can’t think of another building system that’s so vastly underutilized,” he says. “I think we in the design profession have been too timid. Earth building has such great potential, tremendous potential. But we seem to be afraid of ourselves when it comes to the idea of shaping our environment. Up with the earth!”