Standard Methods of Molecular Weight Measurement: Part II

3.1 Sedimentation Equilibrium and Sedimentation Velocity Both sedimentation methods referenced in the heading can be performed in the same standard analytical ultracentrifuge, so the two will treated together, although the physics of M measurement are distinct.

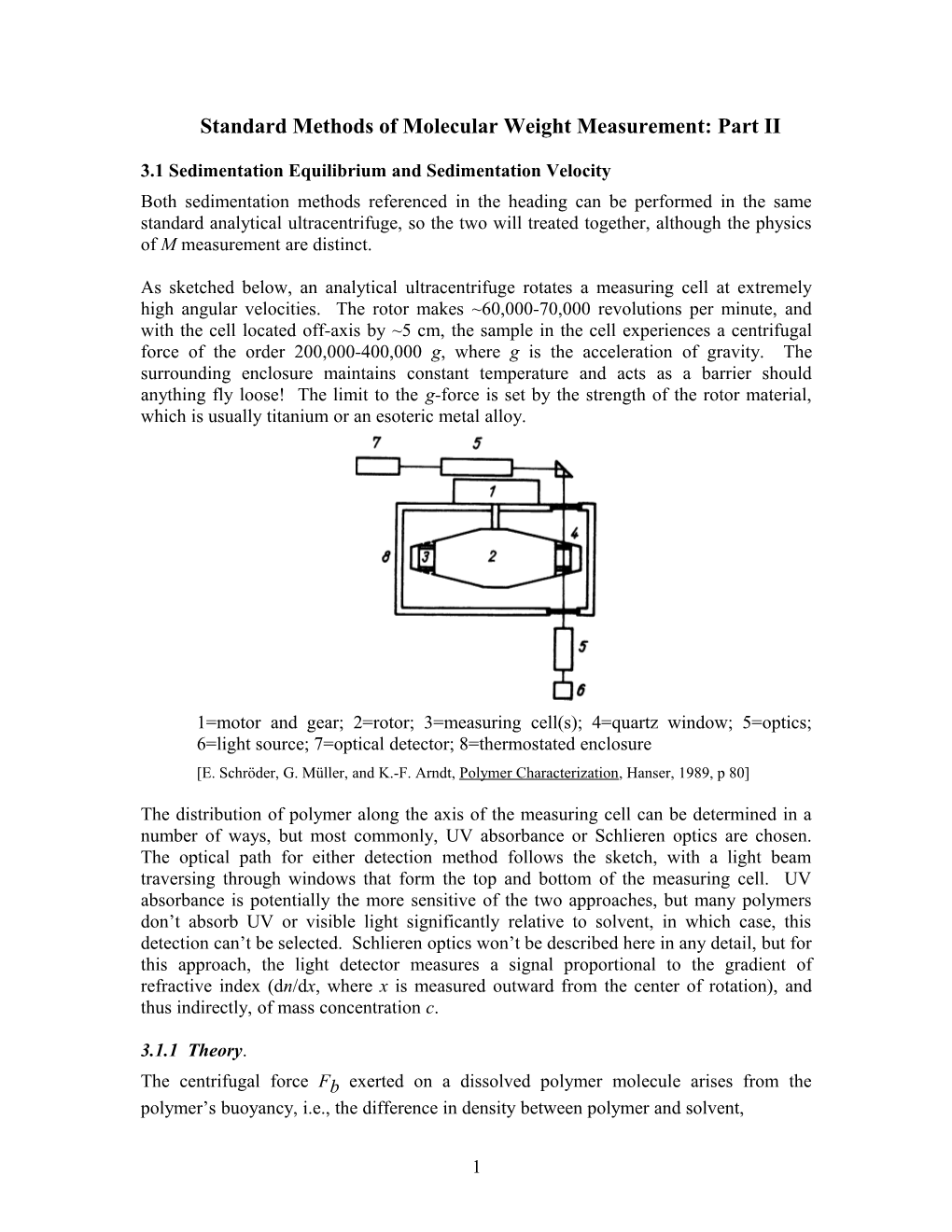

As sketched below, an analytical ultracentrifuge rotates a measuring cell at extremely high angular velocities. The rotor makes ~60,000-70,000 revolutions per minute, and with the cell located off-axis by ~5 cm, the sample in the cell experiences a centrifugal force of the order 200,000-400,000 g, where g is the acceleration of gravity. The surrounding enclosure maintains constant temperature and acts as a barrier should anything fly loose! The limit to the g-force is set by the strength of the rotor material, which is usually titanium or an esoteric metal alloy.

1=motor and gear; 2=rotor; 3=measuring cell(s); 4=quartz window; 5=optics; 6=light source; 7=optical detector; 8=thermostated enclosure [E. Schröder, G. Müller, and K.-F. Arndt, Polymer Characterization, Hanser, 1989, p 80]

The distribution of polymer along the axis of the measuring cell can be determined in a number of ways, but most commonly, UV absorbance or Schlieren optics are chosen. The optical path for either detection method follows the sketch, with a light beam traversing through windows that form the top and bottom of the measuring cell. UV absorbance is potentially the more sensitive of the two approaches, but many polymers don’t absorb UV or visible light significantly relative to solvent, in which case, this detection can’t be selected. Schlieren optics won’t be described here in any detail, but for this approach, the light detector measures a signal proportional to the gradient of refractive index (dn/dx, where x is measured outward from the center of rotation), and thus indirectly, of mass concentration c.

3.1.1 Theory. The centrifugal force Fb exerted on a dissolved polymer molecule arises from the polymer’s buoyancy, i.e., the difference in density between polymer and solvent,

1 where meff is the effective mass of one molecule in the solvent, is the angular velocity of the rotor, NA is Avogadro’s number, 1 is the solvent density, and v2 is the partial specific volume of polymer, effectively the reciprocal of the polymer density when dissolved in the solvent. For simplicity, a polymer denser than solvent is assumed in the subsequent analysis, directing Fb outward, in the direction of increasing x. The opposite case is almost as common.

A balance of Fb with the polymer’s hydrodynamic resistance Fh to translational motion through stationary solvent sets the sedimentation velocity dx/dt, dx F = f h dt where f is the chain’s friction coefficient. The sedimentation coefficient s relates dx/dt to the centrifugal acceleration 2x, dx s = dt w 2x s is commonly expressed in Svedberg units, where 1 Svedberg equals 10-13 s. Equating Fh to Fb, an expression for M is obtained fsN M = A (1- r1v2 ) By adopting the Einstein equation for solute friction, f = kT/D, where k is the Boltzmann constant, T is temperature, and D is the polymer’s tracer diffusion coefficient in the solvent (evaluated at dilute conditions), the so-called Svedberg equation is obtained, RTs M = (1- r1v2 )D which connects sedimentation to tracer diffusion while offering a route to M if s is measured, and D and v2 are known (or measured separately).

Solving for x in the equation that defines s, one finds that a narrow band of homogeneous polymer migrates such that band position changes exponentially in time t.

Diffusion about the mean band position during centrifugal migration has been ignored so far. Adding diffusion to the force balance leads to a sedimentation-diffusion governing equation (Lamm’s equation) in the form of a differential equation, ¶c 1 ¶ й 2 2 ¶c щ = - scw x + Dx ¶t x ¶x лк ¶x ыъ When D is set to zero, this equation describes migration of a solute concentration pulse at a velocity s2x, reproducing the result of the simpler analysis given above.

2 When equilibrium across the cell is achieved at large t, i.e, when dc/dt=0 at all x, outward sedimentation balances inward diffusion down a steady c gradient. One can solve the same differential equation for c and then eliminate D and s through the Svedberg equation, finding for the steady c profile, й M 2 2 2 щ c = cb exp (1- r1v2 )w (x - xb ) лк2 RT ыъ where at x=xb, the position of the outer end of the measuring cell, the no polymer flux condition allows the polymer to accumulates to c=cb, a parameter dependent on the original mass of polymer added to the cell. With v2 known by a separate density measurement, M can be calculated at equilibrium by measuring c at any two positions x, c 2RT ln 2 c1 M = 2 2 2 (1 - r1v2 )w (x2 - x1 ) where “1” and “2” designate c and x at the two positions.

For a polydisperse system at equilibrium, each component of molecular weight Mi and concentration ci obeys a concentration profile analogous to that given above, and adding these profiles together to obtain c, dc w2x(1 - r v ) c M = 1 2 е i i dx RT This equation can be manipulated to find various molecular weight averages; the formulae will not be given here.

The first equation given for M, derived in absence of diffusion, suggests that for large M (a condition which restricts diffusion of away from the mean band position because D is small) s should correlate with M similarly to f, i.e., with a power law, s = KMa Coefficients K and a, derived from a set of nearly monodisperse samples, are tabulated for many polymer/solvent combinations. When the two parameters are available in this manner, the velocity sedimentation method provides the full M distribution if the distribution of s is measured.

3.1.2 Practice Measuring cells are from 0.2 to 3 cm in length and have a segment shape such that cell width increases toward the bottom (sector angle ~ 2-4º). The initial distribution of polymer within the cell is uniform, i.e., c is not a function of x.

To measure sedimentation velocity, the rotor speed is set so high that diffusion of polymer is negligible. Then, at some intermediate time t, well before equilibrium across

3 the cell is achieved, one can envisage transient c profiles much as drawn below for the case of two discrete M fractions in the sample.

The top curve corresponds to complete neglect of diffusion. Each “step” corresponds to a sharp interface between two regions, one in which the concentration of a specified polymer fraction is uniform (for x greater than the step position) and one where this polymer fraction is absent (for x less than the step position). Adding diffusion, these interfaces are smeared, as shown in the middle sketch; the new profile parallels an the absorbance measurement of c. With Schlieren optics, which detects the gradient of c, measurement yields the bottom sketch.

Considering a single component polymer solution, as the c step approaches the bottom of the cell at larger t, its character changes, reflecting approach to the equilibrium c profile. This time evolution is sketched below:

Whereas initial concentration co was uniform, at intermediate t, a c step migrates to the right. Simultaneous to migration, at the bottom of the cell, c rises above co as polymer arrives in this region and is trapped by the closed cell end. Eventually, the migrating step

4 merges with the perturbed bottom region and a continuously increasing c profile is obtained. Eventually, at equilibrium, the profile becomes time-invariant.

Only at intermediate t will a c step migrate as described in the theory derived without diffusion. Measurements in this t domain made with Schlieren optics for the theta system of polystyrene migrating in cyclohexane are shown below. As the simplified theory predicts, polymers move such that their x-positions move exponentially in t. The linearity of the semilog plot for specified integrated mass fractions I (M) are shown further down; slope differences among the I(M) lines reveal there is a distribution of M, the different fractions migrating at different s.

For this model system, s = 1.55x10-2 M0.5 where M is in g/mol and s is in units of Svedbergs. The M distribution calculated using this s-M correlation is given in cumulative form at the top of the next page.

As described above: t is time in minutes

As described above: I is integrated mass fraction

5 Integral weight fraction distribution of M. The five points correspond to the 5 slopes of the preceding plot.

[all plots from: E. Schröder, G. Müller, and K.-F. Arndt, Polymer Characterization, Hanser, 1989, pp 88-89]

Issues: An analytical ultracentrifuge is very expensive, ~$300-400,000. The volume of sample is small (<1 ml of dilute solution). One must have a pycnometer to measure v2 . The velocity method is fast (hours) but the equilibrium method is slow (days); for this reason, the equilibrium method is rarely performed. There is really no upper M limit, especially for the velocity method. The low M limit is established by the magnitude of g-force available. The larger is v2 and the larger is dn/dc (or absorbance), the better is accuracy. Accuracies of 5-10% are typical for model systems. Unless s is known as a function M by correlation with M standards, the velocity method requires input of D. Ideally, one can get D for a narrow distribution sample by the width of the step of c. For a polydisperse sample, the M- dependence of D convolutes onto the M-dependence of s, making the velocity measurement hard to interpret. Some investigators have connected a light scattering detector to the measuring cell such that unmixed sample fractions are streamed to the light scattering detector for absolute M measurements. The combination gives the absolute M distribution without further assumptions, but operation is tricky. Equilibrium sedimentation in a solvent with a density gradient has often been used to study biopolymers. Use of this approach for synthetic polymers has been extremely rare. A density gradient can be created by adding a cosolute such as sucrose, which rapidly sediments to its own equilibrium concentration profile. Data analysis is more straightforward for a system containing a few discrete molecular species than for a system containing a distribution of species. This makes the method more popular for biopolymers than for synthetic polymers. Although seemingly suitable for studying composition distributions in copolymers, especially graft and block copolymers, over the past ten-fifteen years, I’ve only seen sedimentation used to study branched polymers. In the latter case, measuring M was not the objective.

6 3.2 Solution Viscometry Dilute solution viscometry, the first relative M method to be described, is based on measuring the increase in viscosity as a polymer is added at varying dilute concentrations c to a solvent. The normalized relative change in viscosity is referred to as the “specific” viscosity sp,

h - ho hsp = = hrel - 1 ho where o is the pure solvent viscosity, and rel (=/o) is termed the “relative” viscosity. Dividing sp by c, one obtains the “reduced” viscosity red, which varies linearly with c when c is low. The linear increase is captured in the empirical Huggins equation, 2 hred = [h] + kH[h] c + .. where [] is the “intrinsic” viscosity and kH is the Huggins coefficient. The latter has a value of ~0.3-0.4 in a good solvent and ~0.5 in a theta solvent.

h - h o , cm 3 /g c h o

[ h ] equals extrapolation to c=0

c, g/cm 3

The value of [] captures the degree to which a small increment in c raises . Adding larger polymers at the same c increment causes a greater increase in , as derived in the next subsection.

3.2.1 Theory of Dilute Solution Viscosity To understand the viscosity method, we begin with a relationship derived by Einstein for the viscosity at volume fraction of a dilute suspension of uniformly sized spheres. He found by difficult theory [difficult enough that Einstein made an math error that he had to correct in a 2nd publication] a rather simple result:

= o[1 + 2.5 + …] To connect to polymer solution measurements, we must relate the actual experimental variable c to , which doesn’t have a clear definition for flexible polymer molecules. Assuming that the molecules behave hydrodynamically as rigid spheres, we can assign to each chain in dilute solution a “hydrodynamic radius” Rh. This radius can be interpreted as the size of the sphere that would give a contribution to equal to that from a single

7 polymer. We do not know precisely how Rh relates to the size and structure of the dissolved polymer, but we can be confident that Rh is proportional to any choice of average coil size. Letting C be an undetermined coefficient, we can write, for example,

Rh = CRg

The effective “hydrodynamic volume” Vh of one chain is then, 3 3 3 Vh = (4/3)Rh = (4/3)C Rg Adopting this volume, we next transform c [mass/volume] into , effectively making this step a units conversion, c[mass / vol]V [vol / molecule] N [molecules / mole] f = h A M[mass / mole]

Eliminating and Vh, 3 3 [] = 2.5 (4/3)C NA[Rg /M] The multiplicative factors outside of the […] on the right-hand-side define a universal constant of unknown value. For long enough linear polymers, Rg depends on M raised to a power, Rg M Combining the two previous formulae and gathering the incompletely specified constants into empirical parameters, K and a, [] = KMa where a=3-1. Many values of the constants K and a, called “Mark-Houwink coefficients”, are tabulated in reference books.

If K and a are known a priori for a particular polymer chemistry and solvent, and [] is measured for a sample of the same chemistry in the same solvent, we deduce the sample’s M by direct substitution into the preceding formula.

The value of M obtained in this manner is an average over the sample’s M distribution. To be specific, we subscript the value of M determined in this fashion with a “v”, terming Mv the “viscosity-average” molecular weight, calculated from the M distribution as

a 1/a Mv = (е wiMi ) Experimental determination of v also reveals whether a solvent is a good, marginal, or theta solvent for the tested polymer.

The preceding analysis of polymer dilute solution viscosity assumed that a coiled polymer behaves hydrodynamically as a rigid sphere, an assumption known as the “nonfree-draining” hypothesis since it implies that a nearly time-invariant spherical solvent domain is dragged along with the polymer during flow. One might guess that this

8 hypothesis is awful, as the segment density inside a coil can be quite small. An opposing hypothesis regards polymer chains as “free-draining”, with solvent readily able to penetrate and flow within the coil. To judge between the nonfree-draining and free- draining hypotheses, solvent flow must be analyzed within a polymer coil, a theoretically difficult problem. Those who do this sort of analysis report that the free-draining approach fails for dissolved high molecular weight polymers. Although many texts debate the two draining hypotheses at length, we need only to recognize that the nonfree- draining hypothesis is correct. Perhaps a physical analogy can best explain the result, that a tenuous porous solute effectively immobilizes all solvent in its interior: Although the branches and leaves of a bush might be sparse (comparable to the sparseness of segments within the envelop of a polymer coil), the branches and leaves effectively screen a strong wind so that air at the bush’s center is nearly stagnant.

For linear homopolymers, the Mark-Houwink relationship is only valid asymptotically, i.e., at large M, where the exponent a must have one of three values, 0.33, 0.5, or 0.6, corresponding to poor, theta, and good solvent conditions. Although other values of a are reported, any value other than these three implies that measurements were not made in the asymptotic high M regime. If so, the power law relationship is only approximate, extending over a limited range of M. The values of K and a are typically determined by examining a series of M standard polymers. Molecular weights of the standards could be determined by any method but typically these values are determined by light scattering.

3.2.2 Practice of Dilute Solution Viscometry To assure that the tested polymer solution is dilute, viscosity measurements are performed over the range 1.0<rel<2.0 (the coil overlap concentration c* is commonly defined by this upper limit). The solution thus has a viscosity within a factor of 2 of the solvent, and since viscosities of most simple solvents are in the range of centipoises, capillary viscometers are preferred for intrinsic viscosity measurements. Other types of commercially available viscometers don’t have the accuracy for such low viscosity fluids. For very high M polymers, however, as discussed below, one might be able to use a rotational viscometer with cylindrical Couette fixtures. Viable viscometers of this type were once commercial, but few remain in use today.

Two capillary viscometers are popular, Ubbelhode and Ostwald, shown left and right, respectively on the following sketch:

In both types, one measures the time t needed for a solution or solvent to drain through the test section of a glass capillary under the action of gravity. The Ubbelhode type is

9 superior, since the drainage height doesn’t vary over the duration of the experiment. Texts often describe various hydrodynamic corrections for entrance/exist effects, but in modern capillary viscometers, assuming laminar flow, is almost perfectly proportional to t, so these corrections aren’t needed.

However, appropriate values of t ARE necessary. If t for solvent is 60 s, the lowest solution t will be about 66 sec (i.e., rel=1.1). If the measurement uncertainty is 0.2 s (the human reaction time during use of a stop watch), an error in sp of the order 0.4/6= will be incurred, about 5-10%. Upon extrapolation to zero c, this level of error can generate larger uncertainty in [], perhaps of the level 50%. The consequential error in M is even larger. If a stopwatch is to be used, I recommend selection of a viscometer such that t is greater than 150 s. The timing problem is much reduced if t is measured automatically, as done in some commercial instrument packages. Drainage time is typically controlled through the length and diameter of the capillary, so different capillaries are often stocked in a lab that does these measurements routinely.

Many instruments allow dilution inside the viscometer; this feature requires a larger bottom bulb. One simple adds an aliquot of solvent after the preceding measurement is complete.

Issues: Temperature control can be crucial, since viscosities of simple fluids vary exponentially with temperature. For example, the viscosity of water drops by more than 10% as temperature rises from 20ºC to 25ºC. Temperature control is typically achieved by immersing the viscometer in a transparent fluid bath with temperature controlled to better than 0.1ºC. Measurements in open air are only qualitative, and quantitative measurements in a bath at high temperature are extremely difficult. Dust has a large effect, increasing artificially raising t. The problem is exacerbated by the small diameter of the capillary. Solutions/solvents should be filtered directly into the viscometer. Since the solution moves up and down, polymer can readily be adsorbed or deposited on the capillary walls as the solution dries between runs. There is no easy way to clean the walls other than to add an aggressive solvent. Co-solutes can be a killer. I tried to measure the molecular weight of a polymer that was dissolved in a surfactant solution, but I could never eliminate the bubbles generated by siphoning the solution up the capillary. The presence of even a minute bubble substantially raised t. Polymers larger than about 0.5-1x106 g/mol generate shear-thinning solutions, and the appropriate viscosity for M determination is that at zero shear rate. Many capillaries generate shear rates of several hundred s-1. To avoid shear thinning, one commercial Ubbelhode design has four test sections in sequence, each with a different capillary diameter and thus producing a different shear rate. The four measured drainage times can be extrapolated to the drainage time corresponding to zero shear rate. Often, however, a large extrapolation is necessary, making the

10 final measured quite uncertain. I would never attempt the solution viscosity method with standard capillaries for M greater than 107 g/mol even if supporting literature exists. Values above M~106 g/mol are open to question. Several tactics have been suggested to extend solution viscosity measurements to higher M, including accordion-like capillaries that drain on the tens-of-minute timescale. To avoid the problems of the last two bullets, I have used a rotational viscosmeter made by Contraves, and I have also built a so-called Zimm-Crothers viscometer. Both viscometers have extremely high torque sensitivity and can monitor viscosities of the appropriate magnitude at shear rates of 1 s-1. (Indeed, I could measure the viscosity of simple solvents to an accuracy of better than 1% in the latter instrument. Unfortunately, it was extremely difficult to operate and clean.) No appropriate rotational viscometer for intrinsic viscosity measurement is currently commercial available. In absence of calibration standards, what can one do? Not much. Unlike some other relative methods, one cannot make use of calibration standards of a different chemical type – the value of K varies too widely. Many industries characterize the size of their polymer products through specific viscosity at some standard polymer concentration. One should never extrapolate to find M outside the range in which the Mark- Houwink coefficients were obtained. Although solution viscosity dominated M measurements from the period 1940- 1990, usage has dropped rapidly with the advent of simpler/cheaper light scattering instruments and GPCs. Most uses today relate to the probing of polymer architecture, not the measurement of M.

11 3.3 Gel Permeation Chromatography Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC), also called Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), has become the most practiced method of M measurement for synthetic polymers. Since modern column packing particles are rigid solids, able to withstand large pressures, the allusion to gel packing particles in the older name is a little inappropriate, but still this name is the most widely employed for the method. GPC does not really offer a method for M measurement but rather a method for the separation by M of mixed polymer fractions. Only when the separation is calibrated, i.e. the position of an eluted fraction can be related to the fraction’s M, is the method capable of measuring M.

The operation of a GPC instrument is as for any chromatographic method except that the interactions of the solute with the packing are principally steric (entropic); in other forms of chromatography, reversible adsorption (enthalpy) is the dominant interaction. The degree of separation by GPC is generally much smaller than in other forms of chromatography, with peaks for all M values spread over about a two-fold range of elution volume, so maintenance of a constant chromatographic flow rate is crucial. Most practitioners add a low M marker to each polymer sample so as to track flow rates relative to flow rates maintained during calibration runs; variation of flow rate should be less than ~0.3%. If the flow rate shifts by 1%, depending on the calibration curve, errors in M of order 25% can be incurred.

The basic elements of a GPC instrument are sketched below. Packed Columns

Sample Injector Pump Detector

Solvent Reservoir Waste

flow partitioning K SEC

12 The partition coefficient KSEC is the ratio, at equilibrium, of polymer concentration inside the packing pores to the concentration outside these pores, and the separation relies on the M dependence of this coefficient. The range of KSEC is 0 As a polymer bands sweeps by a packing particle, one might question whether the polymer enjoys a long enough residence time to equilibrate between the inside and outside of the packing particle. However, chromatographic theory shows that equilibration at this local level is not needed. Instead, equilibration is achieved over a column length called the Height Equivalent of a Theoretical Plate (HETP), which typically corresponds to a column length of several packing particle diameters. Efficiency of a GPC column is assessed by the number of theoretical plates present for a low molecular weight species with KSEC =1,and the number of HETPs is usually in the tens of thousands for a good column. Since equilibration at some level is established between intra- and inter-particle pore volumes, the separation (positions of peaks) across a full column should be independent of flow rate, a fact confirmed by many experiments. However, HETP does depend on flow rate, and the minimum HETP for most columns is at a lower flow rate than chosen for experiments (conventional value: 1 ml/min). Operating at the minimum HETP maximizes peak resolution, since peak widths are minimized at this condition. Twenty years ago, the typical GPC set-up had five columns in series, each of different pore size so as to separate different M ranges. Such a set-up could create good resolution across the range 1,000 g/mol The role of KSEC is highlighted in the next figure: Vr = Vo + KSECVp Vr = retention volume Vo = interstitial packing volume Vp = pore volume KSEC = partition coefficient DSc /k KSEC = e Sc = confinement entropy Chains lose configurational entropy upon entering a pore (Sc<0) Retention Time or Volume 13 The value of KSEC depends on the polymer-polymer confinement geometry and size ratio, as sketched below. Model Configurational Measure in Experiment Entropy Loss 1.0 1.0 Log K Log K SEC SEC Solute size Solute size The typical size ratio of polymer-to-pore is about 0.1 to 0.001, allowing equilibration to be achieved rapidly and thus to minimize HETP. However, a larger ratio would create larger degrees of polymer separation, since KSEC is more sensitive to solute size when the polymer-to-pore size ratio is about unity. Calibration is the major issue in GPC. The conventional calibration is by M standards of the same polymer chemistry as the test sample. This procedure is illustrated in the figure on the top of the next page and was mentioned in the first handout. Good separation is only achieved across the “operating range”, where logM is approximately linear in Vr. The operating range depends on the pore sizes and pore size distributions of the packing beads, and in a mixed bead column – packed with beads of various pore sizes - this range can extend over several orders of magnitude in M, bounded by total exclusion (upper M limit) and total permeation (lower M limit). Linearity of this plot is not really required, just that a solid correlation between M and Vr. When Vr is highly sensitive to M, the logM vs. Vr plot has a low slope in the operating range; however, this feature means that the column’s M range is sharply limited, perhaps to as little as one order-of-magnitude. Note that Vr fundamentally distinguishes M fractions. Most instruments monitor fractions by their elution time t rather than their elution volume Vr. If so, to connect t to 14 V V o p Operating Range Total Log M exclusion Total permeation V r Chromatogram V r Vr, the flow rate must be kept rigorously constant, as noted before. To monitor Vr during the experiment, needed for precise work, a GPC must have a capability to measure flow rate or collect fractions of constant volume; I am unaware of a commercial instrument that does either. To avoid calibration by standards, which usually are unavailable for a new polymer or even many older ones, universal calibration was devised, a concept exploiting that GPC separation is governed by polymer “size”. As indicated in the top sketch on page 13, the degree of separation (i.e., KSEC and thus Vr) correlates with a molecular size sometimes called the “mean projection length”, the average closest separation of polymer to pore wall computed from the full ensemble of free polymer configurations. Universal calibration recognizes that for a linear flexible homopolymer, all measures of chain size are proportional to each other. Thus, as shown in the discussion of dilution solution viscometry, the product []M, capturing the hydrodynamic size raised to the third power, can be taken as a variable correlating GPC separation. The quality of this correlation is illustrated in the sketch on the top of the next page. Universal calibration eliminates large errors (typically 10-50%) incurred by calibration with M standards of different backbone chemistry, usually polystyrene (organic solvents) or PEO (aqueous solvents). 15 Issues: GPC can be coupled to a M-sensitive detector to reduce errors associated with calibration by standards. With a static light scattering detector, this addition makes the method absolute, while with a viscosity detector, the method remains relative. However, for the latter, assuming universal calibration is valid, results are expressed directly in terms of M. I believe viscosity detection is only warranted when a branched or architecturally complicated polymer is studied; stick with light scattering – it is more rigorous. One only obtains the correct M distribution if all of the sample elutes past the detector(s). If adsorption is a possible complication, one should check that all of the sample has passed the detector by constructing a by-pass from the injection value to the detector. Several issues can complicate the study of high M polymers – (i) Really large open pores structurally weaken the packing particles, and thus, large polymers cannot be studied at the same polymer-to-pore sizes as with smaller polymers. This constraint reduces column efficiency and makes equilibration difficult. (ii) The strain rates in and around the particles may generate hydrodynamic forces large enough to break chains. If this effect is a concern, an eluted fraction should be reinjected to assure that it elutes in its original position (iii) Other exclusion mechanisms may dominate, especially hydrodynamic chromatography, the exclusion of the polymer from the particle surface and not from inside pores. Most aqueous GPC systems require solvent additives to preclude adsorption on the packing. 16