Heritage Matters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apples Catalogue 2019

ADAMS PEARMAIN Herefordshire, England 1862 Oct 15 Nov Mar 14 Adams Pearmain is a an old-fashioned late dessert apple, one of the most popular varieties in Victorian England. It has an attractive 'pearmain' shape. This is a fairly dry apple - which is perhaps not regarded as a desirable attribute today. In spite of this it is actually a very enjoyable apple, with a rich aromatic flavour which in apple terms is usually described as Although it had 'shelf appeal' for the Victorian housewife, its autumnal colouring is probably too subdued to compete with the bright young things of the modern supermarket shelves. Perhaps this is part of its appeal; it recalls a bygone era where subtlety of flavour was appreciated - a lovely apple to savour in front of an open fire on a cold winter's day. Tree hardy. Does will in all soils, even clay. AERLIE RED FLESH (Hidden Rose, Mountain Rose) California 1930’s 19 20 20 Cook Oct 20 15 An amazing red fleshed apple, discovered in Aerlie, Oregon, which may be the best of all red fleshed varieties and indeed would be an outstandingly delicious apple no matter what color the flesh is. A choice seedling, Aerlie Red Flesh has a beautiful yellow skin with pale whitish dots, but it is inside that it excels. Deep rose red flesh, juicy, crisp, hard, sugary and richly flavored, ripening late (October) and keeping throughout the winter. The late Conrad Gemmer, an astute observer of apples with 500 varieties in his collection, rated Hidden Rose an outstanding variety of top quality. -

Handling of Apple Transport Techniques and Efficiency Vibration, Damage and Bruising Texture, Firmness and Quality

Centre of Excellence AGROPHYSICS for Applied Physics in Sustainable Agriculture Handling of Apple transport techniques and efficiency vibration, damage and bruising texture, firmness and quality Bohdan Dobrzañski, jr. Jacek Rabcewicz Rafa³ Rybczyñski B. Dobrzañski Institute of Agrophysics Polish Academy of Sciences Centre of Excellence AGROPHYSICS for Applied Physics in Sustainable Agriculture Handling of Apple transport techniques and efficiency vibration, damage and bruising texture, firmness and quality Bohdan Dobrzañski, jr. Jacek Rabcewicz Rafa³ Rybczyñski B. Dobrzañski Institute of Agrophysics Polish Academy of Sciences PUBLISHED BY: B. DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ACTIVITIES OF WP9 IN THE CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE AGROPHYSICS CONTRACT NO: QLAM-2001-00428 CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE FOR APPLIED PHYSICS IN SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE WITH THE th ACRONYM AGROPHYSICS IS FOUNDED UNDER 5 EU FRAMEWORK FOR RESEARCH, TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT AND DEMONSTRATION ACTIVITIES GENERAL SUPERVISOR OF THE CENTRE: PROF. DR. RYSZARD T. WALCZAK, MEMBER OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES PROJECT COORDINATOR: DR. ENG. ANDRZEJ STĘPNIEWSKI WP9: PHYSICAL METHODS OF EVALUATION OF FRUIT AND VEGETABLE QUALITY LEADER OF WP9: PROF. DR. ENG. BOHDAN DOBRZAŃSKI, JR. REVIEWED BY PROF. DR. ENG. JÓZEF KOWALCZUK TRANSLATED (EXCEPT CHAPTERS: 1, 2, 6-9) BY M.SC. TOMASZ BYLICA THE RESULTS OF STUDY PRESENTED IN THE MONOGRAPH ARE SUPPORTED BY: THE STATE COMMITTEE FOR SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH UNDER GRANT NO. 5 P06F 012 19 AND ORDERED PROJECT NO. PBZ-51-02 RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF POMOLOGY AND FLORICULTURE B. DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ©Copyright by BOHDAN DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES LUBLIN 2006 ISBN 83-89969-55-6 ST 1 EDITION - ISBN 83-89969-55-6 (IN ENGLISH) 180 COPIES, PRINTED SHEETS (16.8) PRINTED ON ACID-FREE PAPER IN POLAND BY: ALF-GRAF, UL. -

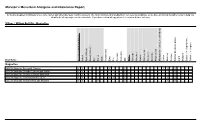

Marston's Menu Item Allergens and Intolerance Report

Marston’s Menu Item Allergens and Intolerance Report All food is prepared in kitchens where nuts, gluten and other allergens could be present. We cannot include all ingredients in our menu descriptions, so we have produced the table below to help you identify the allergens present in each dish. If you have a food allergy please let us know before ordering. Village / Willow Bolt On - Baguettes Dish Name Cereals containing Gluten : Spelt (Wheat) Kamut (Wheat) Barley Crustaceans Fish Peanuts Soybeans Almonds Hazelnut Walnut Pecan nut Pistachio nut Macadamia nut or Queensland Mustard Sesame Sulphur dioxide/sulphites Lupin Molluscs Suitable for Vegans Wheat Rye Oats Eggs Milk Nuts : Cashew nut Brazil nut Celery Suitable for Vegetarians Baguettes VLG LN Baguette Buttermilk Chicken Y Y Y Y Y Y Y VLG LN Baguette Cheddar Cheese and Onion Y Y Y Y Y VLG LN Baguette Chicken & Bacon BBQ Melt Y Y Y Y VLG LN Baguette Tuna Mayonnaise Melt Y Y Y Y Y Y Y VLG LN Baguette Wiltshire Ham and Mustard Y Y Y Y Y Y All food is prepared in kitchens where nuts, gluten and other allergens could be present. We cannot include all ingredients in our menu descriptions, so we have produced the table below to help you identify the allergens present in each dish. If you have a food allergy please let us know before ordering. Village Carvery F.W.E MAY 2018 Dish Name Cereals containing Gluten : Spelt (Wheat) Kamut (Wheat) Barley Oats Crustaceans Fish Peanuts Soybeans Milk Almonds Hazelnut Walnut Pecan nut Pistachio nut Macadamia nut or Queensland Mustard Sesame Sulphur dioxide/sulphites -

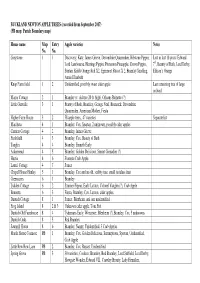

BUCKLAND NEWTON APPLE TREES (Recorded from September 2017) (PB Map: Parish Boundary Map)

BUCKLAND NEWTON APPLE TREES (recorded from September 2017) (PB map: Parish Boundary map) House name Map Entry Apple varieties Notes No. No. Greystone 1 1 Discovery, Katy, James Grieve, Devonshire Quarrenden, Ribstone Pippin, Lost in last 10 years: Edward Lord Lambourne, Herrings Pippin, Pitmaston Pineapple, Crown Pippin, 7th , Beauty of Bath, Lord Derby, Suntan, Kidds Orange Red X2, Egremont Russet X 2, Bramley Seedling, Ellison’s Orange Annie Elizabeth Knap Farm field 1 2 Unidentified, possibly sweet cider apple Last remaining tree of large orchard Manor Cottage 2 1 Bramley (v. old tree 20 ft. high), Orleans Reinette (?) Little Gunville 3 1 Beauty of Bath, Bramley, George Neal, Bismarck, Devonshire Quarrenden, American Mother, Fiesta Higher Farm House 3 2 58 apple trees,, 47 varieties Separate list Marcheta 4 1 Bramley, Cox, Spartan, 2 unknown, possibly cider apples Carriers Cottage 4 2 Bramley, James Grieve Freshfield 4 3 Bramley, Cox, Beauty of Bath Tanglin 4 4 Bramley, Emneth Early Askermead 4 5 Bramley, Golden Delicious, Sunset Grenadier (?) Hestia 4 6 Evereste Crab Apple Laurel Cottage 4 7 Sunset Chapel House Henley 5 1 Bramley, Cox and an old, scabby tree, small tasteless fruit Greenacres 6 1 Bramley Lydden Cottage 6 2 Sturmer Pippin, Early Laxton, Colonel Vaughn (?), Crab Apple Bennetts 6 3 Fiesta, Bramley, Cox, Laxton, cider apples Duntish Cottage 8 1 Sunset, Blenheim, and one unidentified Frog Island 8 2 & 3 Unknown cider apple, Tom Putt Duntish Old Farmhouse 8 4 Tydemans Early, Worcester, Blenheim (?),Bramley, Cos, 5 unknowns -

Apple, Reaktion Books

apple Reaktion’s Botanical series is the first of its kind, integrating horticultural and botanical writing with a broader account of the cultural and social impact of trees, plants and flowers. Already published Apple Marcia Reiss Bamboo Susanne Lucas Cannabis Chris Duvall Geranium Kasia Boddy Grasses Stephen A. Harris Lily Marcia Reiss Oak Peter Young Pine Laura Mason Willow Alison Syme |ew Fred Hageneder APPLE Y Marcia Reiss reaktion books Published by reaktion books ltd 33 Great Sutton Street London ec1v 0dx, uk www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2015 Copyright © Marcia Reiss 2015 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 978 1 78023 340 6 Contents Y Introduction: Backyard Apples 7 one Out of the Wild: An Ode and a Lament 15 two A Rose is a Rose is a Rose . is an Apple 19 three The Search for Sweetness 43 four Cider Chronicles 59 five The American Apple 77 six Apple Adulation 101 seven Good Apples 123 eight Bad Apples 137 nine Misplaced Apples 157 ten The Politics of Pomology 169 eleven Apples Today and Tomorrow 185 Apple Varieties 203 Timeline 230 References 234 Select Bibliography 245 Associations and Websites 246 Acknowledgements 248 Photo Acknowledgements 250 Index 252 Introduction: Backyard Apples Y hree old apple trees, the survivors of an unknown orchard, still grow around my mid-nineteenth-century home in ∏ upstate New York. -

Apple Pollination Groups

Flowering times of apples RHS Pollination Groups To ensure good pollination and therefore a good crop, it is essential to grow two or more different cultivars from the same Flowering Group or adjacent Flowering Groups. Some cultivars are triploid – they have sterile pollen and need two other cultivars for good pollination; therefore, always grow at least two other non- triploid cultivars with each one. Key AGM = RHS Award of Garden Merit * Incompatible with each other ** Incompatible with each other *** ‘Golden Delicious’ may be ineffective on ‘Crispin’ (syn. ‘Mutsu’) Flowering Group 1 Very early; pollinated by groups 1 & 2 ‘Gravenstein’ (triploid) ‘Lord Suffield’ ‘Manks Codlin’ ‘Red Astrachan’ ‘Stark Earliest’ (syn. ‘Scarlet Pimpernel’) ‘Vista Bella’ Flowering Group 2 Pollinated by groups 1,2 & 3 ‘Adams's Pearmain’ ‘Alkmene’ AGM (syn. ‘Early Windsor’) ‘Baker's Delicious’ ‘Beauty of Bath’ (partial tip bearer) ‘Beauty of Blackmoor’ ‘Ben's Red’ ‘Bismarck’ ‘Bolero’ (syn. ‘Tuscan’) ‘Cheddar Cross’ ‘Christmas Pearmain’ ‘Devonshire Quarrenden’ ‘Egremont Russet’ AGM ‘George Cave’ (tip bearer) ‘George Neal’ AGM ‘Golden Spire’ ‘Idared’ AGM ‘Irish Peach’ (tip bearer) ‘Kerry Pippin’ ‘Keswick Codling’ ‘Laxton's Early Crimson’ ‘Lord Lambourne’ AGM (partial tip bearer) ‘Maidstone Favourite’ ‘Margil’ ‘Mclntosh’ ‘Red Melba’ ‘Merton Charm’ ‘Michaelmas Red’ ‘Norfolk Beauty’ ‘Owen Thomas’ ‘Reverend W. Wilks’ ‘Ribston Pippin’ AGM (triploid, partial tip bearer) ‘Ross Nonpareil’ ‘Saint Edmund's Pippin’ AGM (partial tip bearer) ‘Striped Beefing’ ‘Warner's King’ AGM (triploid) ‘Washington’ (triploid) ‘White Transparent’ Flowering Group 3 Pollinated by groups 2, 3 & 4 ‘Acme’ ‘Alexander’ (syn. ‘Emperor Alexander’) ‘Allington Pippin’ ‘Arthur Turner’ AGM ‘Barnack Orange’ ‘Baumann's Reinette’ ‘Belle de Boskoop’ AGM (triploid) ‘Belle de Pontoise’ ‘Blenheim Orange’ AGM (triploid, partial tip bearer) ‘Bountiful’ ‘Bowden's Seedling’ ‘Bramley's Seedling’ AGM (triploid, partial tip bearer) ‘Brownlees Russett’ ‘Charles Ross’ AGM ‘Cox's Orange Pippin’ */** ‘Crispin’ (syn. -

Peach-Pub-Menu-Updat

COCKTAILS GRAND GINS To make the planet Peachier, plastic will not be found in our A large measure of gin served with Fentimans or Schweppes Tonic, cocktails. If you like a straw, let us know & we’ll serve you a paper one. in a grand coupe with ice & fruit. Try with Fentimans Pink Grapefruit or Elderflower Tonic, or why not go light? Banoffee Martini CLASSIC Discarded Banana Rum | Ron Aguere Caramel Rum | Cotswolds Cream Liqueur 9.50 Tanqueray Dry, crisp, London Dry using only four botanicals. Aperol Spritz With lemon & lime 8.50 Aperol Orange | Prosecco | Soda 8.25 Mahon Xoriguer Pronounced sho-ri-gair. Menorcan family-made gin made from distilled wine & Downhill Racer secret botanicals in wood-fired pot stills. Lazzaroni Amaretto | Havana Club 7 | Pineapple 8.25 ONE LAST Characterful & slightly lighter. With lemon 8.50 Strawberry Daiquiri Hendrick’s Havana Club | Strawberry | Lime 8.50 GLASS A sure favourite with cucumber & rose flavours. With cucumber 9.25 Tawny Old Fashioned Buffalo Trace | Sandeman Tawny Port | Banoffee Martini 9.50 FRUITY Vanilla | Orange | Bitters 10.50 Espresso Martini 8.75 Edinburgh Bramble & Honey Fresh berries with sweet honey. Rich, fruity & rounded, Rhubarb Gin Mule Diplomatico Reserva Exclusiva Rum 4.80 a great combination. With lemon 9.25 Chase Rhubarb & Apple | Ginger | Lime | Mint 8.50 Ron Aguere Caramel Rum 3.50 Slingsby Gooseberry Margarita Lazzaroni Amaretto 3.40 Crafted using famed Harrogate aquifer water & Yorkshire gooseberries. Tangy Olmeca Reposado | Orange Liqueur | Lime 8.50 with sweet, fruit finish. With apple 9.50 Château du Tarriquet, Bas Armagnac, VSOP 4.25 THE LIST Tanqueray Flor de Sevilla Espresso Martini Remy Martin VSOP 4.25 Clean & citrus, flavoured with the classic marmalade Ketel One | Tia Maria | Coffee 8.75 WINE & DRINKS oranges of Seville. -

Traditional Bramley Apple Pie Filling"

APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION OF A TSG COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 509/2006 on agricultural products and foodstuffs as traditional specialities guaranteed. "TRADITIONAL BRAMLEY APPLE PIE FILLING" EC No: UK-TSG-007-0057 1. Name and address of the applicant group: Name: UK Apples & Pears Ltd Address: Forest Lodge Bulls Hill Walford Ross-on-Wye Herefordshire HR9 5RH Tel.: 00 44 (0) 1732 529781 Fax: 00 44 (0) 1732 529781 Email: [email protected] UK Apples & Pears Ltd is a grower owned organisation formed in 1987. It now represents 73% of UK commercial apple and pear producers and has actively participated in EU funded programs to promote the increased consumption of fresh and processed apples in the fresh market, manufacturing, catering and food service industries. 2. Member State or Third Country - United Kingdom 3. PRODUCT SPECIFICATION 3.1 Name(s) to be registered (Article 2 of Commission Regulation 1216/2007) “Traditional Bramley Apple Pie Filling”. 3.2 Whether the name is specific in itself expresses the specific character of the agricultural product or foodstuff The single purpose culinary variety Bramley has a unique blend of low dry matter, high malic acid and low sugar levels which produce the characteristic tangy Bramley flavour in the Traditional Bramley Apple Pie Filling processes. The use of the term “Traditional” denotes that no modern preservatives are used. 3.3 Whether reservation of the name is sought under Article 13(2) of Regulation 509/2006 X Registration with reservation of the name 1 Registration, without reservation of the name 3.4 Type of product [as in Annex II] Group 1.6: Fruit, vegetables and cereals, fresh or processed 3.5 Description of the agricultural product or foodstuff to which the name under point 3.1. -

European Apple Sawfly

European Apple Sawfly There is evidence that the sawfly has some slight varietal preferences. A larger than average number of EA fruit were attacked on earlier blooming and longer CULTIVAR Sawfly blooming apple varieties. This was not the case across Ant 48 3 the board, but was recordable. Bowing 3 Breaky 3 Also, varieties which tend to set heavily had a larger Burgundy 3 percentage of attack. This was accentuated in those Cranberry 3 that tend to set in a “rope” of fruits (clustering along Dolgo 3 the branch). The significance of this condition is that it Early Harvest 3 allows easier apple to apple infection of a single larva. Equinox 3 Heavier setting varieties such as Prairie Spy and Liberty Greensleeves 3 had higher damage, as did roping varieties like Haralred 3 Patterson, and various crabs. This close proximity of Honeycrisp 3 fruit to fruit was also higher in attack in varieties that Hyslop Crab 3 pair, like Oriole which almost always occurs as two Kazakh 761 (k-17) 3 apples tightly joined. Keepsake 3 It should be noted, that nearly all varieties had some Leo 3 damage. Some badly affected cultivars did not appear Liberty 3 to line up to any characteristics as noted above. Lodi 3 Keepsake, for instance (neither early blooming, nor Mantet 3 tightly clustered in 2014) had 60% of its fruit attacked in McIntosh 3 our count. There likely exists no truly e.a.s. resistant Melba 3 variety, though some categories of apple apparently are Milwaukee 3 more likely to have greater damage if unregulated. -

The Social and Cultural Value of the Apple and the Orchard in Victorian England

The social and cultural value of the apple and the orchard in Victorian England Joanna Crosby A thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. Department of History University of Essex Date of submission with corrections – January 2021 (Total word count: 79,840) Joanna Crosby January 2021 Abstract This thesis argues that the apple and the orchard were of greater significance to the Victorians than has been previously realised. This thesis brings together an investigation into the economic value of the apple crop and its associated goods and services, with an exploration of how the apple and the orchard were represented and received in cultural and social constructs. This thesis argues that the economic worth of the apple was greater than the commodity value of the raw crop of apples. That value itself has been underestimated due to the difficulties of calculating the amount of land used for orchards and the profit obtainable. The apple had a wider economic value, helping to expand the sectors of commercial horticulture, domestic gardening and food. Representations of the apple and of orchards drew on Classical landscapes, Christian allegory or the pre-Christian cultures in Europe to give authority to the meanings of an apple placed in a painting. These associations were brought together in the writing about, and the actual performance of, wassailing in the orchards at Christmas. The conclusions state that the economic value of the apple was greater than had been previously thought, and that the network of apple-related trades and livelihoods was extensive. The conclusions from the social and cultural investigation were that the appreciation of the apple was at its height in Victorian England, when the Victorians responded to increasing industrialisation and urban growth by using the apple symbolically to represent values of ‘Englishness’ through an idealised rural past. -

Apple Varieties at Lathcoats Farm

Apple Varieties at Lathcoats Farm All the varieties listed below are available, ready picked, in season in our farm shop. All the apples are grown in our orchards here in Galleywood. VARIETY DATE PLACE OF ORIGIN ON SALE SEASON DISCOVERY 1949 ESSEX AUG SHORT FESTIVAL 1950s FRANCE AUG SHORT QUEEN 1858 BILLERICAY AUG MEDIUM TYDEMAN’S EARLY 1929 KENT AUG SHORT LAXTON’S FORTUNE 1904 BEDFORD SEP SHORT WORCESTER PEARMAIN 1894 WORCESTER SEP SHORT JAMES GRIEVE 1893 SCOTLAND SEP SHORT ALKMENE 1930 GERMANY SEP SHORT BRAMLEY 1809 NOTTS SEP LONG LORD LAMBOURNE 1907 BEDFORD SEP MEDIUM CHELMSFORD WONDER 1870 CHELMSFORD SEP MEDIUM ST EDMUND’S PIPPIN 1875 SUFFOLK SEP SHORT RED ELSTAR 1972 HOLLAND SEP MEDIUM ADAMS PEARMAIN 1826 HEREFORD OCT MEDIUM CORNISH GILLIFLOWER C1800 CORNWALL OCT MEDIUM HONEYCRISP C1960 MINNESOTA OCT MEDIUM TEMPTATION 1990 FRANCE OCT MEDIUM TOPAZ LATE C20 CZECH REPUBLIC OCT MEDIUM MERIDAN 2000 KENT OCT MEDIUM PINOVA 1986 GERMAY OCT MEDIUM CRISPIN 1930 JAPAN OCT MEDIUM COX’S ORANGE PIPPIN 1825 BUCKS OCT LONG Please Turn Over for more varieties Page | 1 Apple Varieties at Lathcoats Farm All the varieties listed below are available, ready picked, in season in our farm shop. All the apples are grown in our orchards here in Galleywood. VARIETY DATE PLACE OF ORIGIN ON SALE SEASON EGREMONT RUSSET 1872 UK OCT LONG BLENHEIM ORANGE 1740 OXON OCT MEDIUM SPARTAN 1926 CANADA OCT MEDIUM ASHMEAD’S KERNEL 1700 GLOUCESTER OCT MEDIUM GALA 1934 NEW ZEALAND SEP LONG RIBSTON PIPPIN 1707 YORKS OCT MEDIUM KIDDS ORANGE 1924 NEW ZEALAND OCT MEDIUM JONAGORED 1943 USA OCT LONG LAXTON’S SUPERB 1897 BEDFORD OCT SHORT CHIVERS DELIGHT 1936 CAMBS OCT MEDIUM FALSTAFF 1966 KENT OCT MEDIUM WINTER GEM 1985 KENT OCT SHORT EDEN 1971 QUEBEC OCT LIMITED CHRISTMAS PIPPIN 2011 SOMERSET OCT LIMITED LITTLE PAX 2014 ISLE OF WIGHT OCT LIMITED BRAEBURN 1952 NEW ZEALAND NOV LONG D’ARCY SPICE 1785 ESSEX NOV MEDIUM LATHCOATS RED JOYCE’S CHOICE Page | 2 . -

Grazed Orchards in Northern Ireland

System report: Grazed Orchards in Northern Ireland Project name AGFORWARD (613520) Work-package 3: Agroforestry for High Value Trees Specific group Grazed orchards in Northern Ireland, UK Milestone Contribution to Deliverable 3.7 (3.1): Detailed system description of a case study system Date of report 30 November 2015 Authors Jim Mc Adam and Frances Ward, Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute, Manor House, Loughgall, Co Armagh, BT61 8JB, UK Contact [email protected] Approved Anastasia Pantera (11 April 2016) Paul Burgess (15 April 2016) Contents 1 Context ............................................................................................................................................. 2 2 Background ...................................................................................................................................... 2 3 Update on field measurements ....................................................................................................... 3 4 Description of system ...................................................................................................................... 3 5 Description of the tree component ................................................................................................. 8 6 Trial results ....................................................................................................................................... 8 7 Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................