ADNAN SYED, September Term, 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Romancing race and gender : intermarriage and the making of a 'modern subjectivity' in colonial Korea, 1910-1945 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9qf7j1gq Author Kim, Su Yun Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Romancing Race and Gender: Intermarriage and the Making of a ‘Modern Subjectivity’ in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Su Yun Kim Committee in charge: Professor Lisa Yoneyama, Chair Professor Takashi Fujitani Professor Jin-kyung Lee Professor Lisa Lowe Professor Yingjin Zhang 2009 Copyright Su Yun Kim, 2009 All rights reserved The Dissertation of Su Yun Kim is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………………...……… iii Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………... iv List of Figures ……………………………………………….……………………...……. v List of Tables …………………………………….……………….………………...…... vi Preface …………………………………………….…………………………..……….. vii Acknowledgements …………………………….……………………………..………. viii Vita ………………………………………..……………………………………….……. xi Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………. xii INTRODUCTION: Coupling Colonizer and Colonized……………….………….…….. 1 CHAPTER 1: Promotion of -

Rabia Chaudry C/O Macmillan Speakers Bureau 175 Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10010 (646) 307-5544

SPOTLIGHT CLE: THE MURDER CASE OF STATE v. ADNAN SYED CLE Credit: 1.0 Wednesday, June 21, 2017 2:25 p.m. - 3:25 p.m. Exhibit Hall 2 Owensboro Convention Center Owensboro, Kentucky A NOTE CONCERNING THE PROGRAM MATERIALS The materials included in this Kentucky Bar Association Continuing Legal Education handbook are intended to provide current and accurate information about the subject matter covered. No representation or warranty is made concerning the application of the legal or other principles discussed by the instructors to any specific fact situation, nor is any prediction made concerning how any particular judge or jury will interpret or apply such principles. The proper interpretation or application of the principles discussed is a matter for the considered judgment of the individual legal practitioner. The faculty and staff of this Kentucky Bar Association CLE program disclaim liability therefore. Attorneys using these materials, or information otherwise conveyed during the program, in dealing with a specific legal matter have a duty to research original and current sources of authority. Printed by: Evolution Creative Solutions 7107 Shona Drive Cincinnati, Ohio 45237 Kentucky Bar Association TABLE OF CONTENTS The Presenter .................................................................................................................. i The State v. Adnan Syed ................................................................................................ 1 Hae's Disappearance.......................................................................................... -

Read Book Adnans Story: the Search for Truth and Justice After Serial Ebook, Epub

ADNANS STORY: THE SEARCH FOR TRUTH AND JUSTICE AFTER SERIAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Rabia Chaudry | 352 pages | 06 Sep 2016 | St. Martin's Press | 9781250087102 | English | United States Adnans Story: The Search for Truth and Justice After Serial PDF Book Other theories discussed in this book bordered on conspiracy theory level thinking, which left me more skeptical. The book includes letters from Adnan, snippets from interviews, sections of the trial and moments from Serial which all combine to make a rather overwhelming book; there were times when I was listening to it I read the audiobook that I had to stop playing it and take a break. Corona Notes: Meet the Moment 3 months ago. The summer of has proven to be a pretty good few months for Adrian Syed. Godless : A Netflix Original Review. So, it's kind of fitting that I decided to read the book about Adnan Syed, Adnan's Story, instead of listening to the podcast. See all 8 - All listings for this product. I was completely engrossed in the Serial podcast so this book was a must-read for me. Make an offer:. My advice, listen to Serial, and research updates on this case. It will make you angry. Serial told Only Part of the Story In early , Adnan Syed was convicted and sentenced to life plus thirty years for the murder of his ex-girlfriend Hae Min Lee, a high school senior in Baltimore, Maryland. Link to full review below! My boyfriend kept trying to get me to listen to podcasts and I refused, due to always listening to books on CD instead. -

When Podcast Met True Crime: a Genre-Medium Coevolutionary Love Story

Article When Podcast Met True Crime: A Genre-Medium Coevolutionary Love Story Line Seistrup Clausen Stine Ausum Sikjær 1. Introduction “I hear voices talking about murder... Relax, it’s just a podcast” — Killer Instinct Press 2019 Critics have been predicting the death of radio for decades, so when the new podcasting medium was launched in 2005, nobody believed it would succeed. Podcasting initially presented itself as a rival to radio, and it was unclear to people what precisely this new medium would bring to the table. As it turns out, radio and podcasting would never become rivals, as podcasting took over the role of audio storytelling medium – a role that radio had abandoned prior due to the competition from TV. During its beginning, technological limitations hindered easy access to podcasts, as they had to be downloaded from the Internet onto a computer and transferred to an MP3 player or an iPod. Meanwhile, it was still unclear how this new medium would come to satisfy an audience need that other types of storytelling media could not already fulfill. Podcasting lurked just below the mainstream for some time, yet it remained a niche medium for many years until something happened in 2014. In 2014, the true crime podcast Serial was released, and it became the fastest podcast ever to reach over 5 million downloads (Roberts 2014). After its release, podcasting entered the “post-Serial boom” (Nelson 2018; Van Schilt 2019), and the true crime genre spread like wildfire on the platform. Statistics show that the podcasting medium experienced a rise in popularity after 2014, with nearly a third of all podcasts listed on iTunes U.S. -

APPENDIX 1A APPENDIX a ______IN the COURT of APPEALS of MARYLAND September Term, 2018 ______

APPENDIX 1a APPENDIX A _________ IN THE COURT OF APPEALS OF MARYLAND September Term, 2018 _______ STATE OF MARYLAND v. ADNAN SYED _______ No. 24 ________ Appeal from the Circuit Court for Baltimore City Case No. 199103042 through 199103046 _______ Argued: November 29, 2018 _______ Barbera, C.J. Greene McDonald Watts Hotten Getty Adkins, Sally D., (Senior Judge, Specially Assigned), JJ. _______ Opinion by Greene, J. 2a Watts, J. concurs. Barbera, C.J., Hotten and Adkins, JJ., concur and dissent _______ Filed: March 8, 2019 _______ In the present case, we are asked to reconsider the decision of a post-conviction court that granted the Respondent, Adnan Syed, a new trial. That decision was affirmed in part and reversed in part by our intermediate appellate court with the ultimate disposition—a new trial—remaining in place. The case now stands before us, twenty years after the murder of the victim, seventeen-year-old high school senior Hae Min Lee (“Ms. Lee”). We review the legal correctness of the decision of the post-conviction court and decide whether certain actions on the part of Respondent’s trial counsel violated Respondent’s right to the effective assistance of counsel. FACTUAL AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND We shall not endeavor to replicate the thorough, carefully-written and well-organized Opinion, penned by then-Chief Judge Patrick Woodward, of the Court of Special Appeals in this case. For a more exhaustive review of the underlying facts, evidence presented at trial, and subsequent procedural events involving Respondent’s (hereinafter “Respondent” or “Mr. Syed”) conviction of first-degree murder of his ex-girlfriend, we direct readers to the Opinion of that court. -

Challenging the Privileging of Objectivity in Serial‑Style Podcasts

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. This Is your warning : challenging the privileging of objectivity in serial‑style podcasts Siti Sarah Daud 2017 Siti Sarah Daud. (2017). This Is your warning : challenging the privileging of objectivity in serial‑style podcasts. Master's thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. http://hdl.handle.net/10356/72879 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/72879 Downloaded on 24 Sep 2021 08:25:44 SGT Privileging Objectivityof in THIS IS YOUR WARNING: Challenging the Serial - style Podcasts THIS IS YOUR WARNING: Challenging the Privileging of Objectivity in Serial-style Podcasts Siti SarahSiti Binte Daud SITI SARAH BINTE DAUD SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES 2017 2017 Daud i THIS IS YOUR WARNING: Challenging the Privileging of Objectivity in Serial-style Podcasts Siti Sarah Binte Daud School of Humanities A thesis submitted to Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. 2017 Daud ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Just like a podcast, a Masters’ Thesis has a whole team preparing the one single voice that goes out into the world. Here they are. To Prof Sam, thank you for taking me under your wing when I was just another name on the register and building me up into someone capable of doing an entire MA. I could not have dreamed up a better mentor; your endless patience, encouragement and steadfast belief in me and this project has made all the difference, and I will never be able to thank you enough. To Kevin, this whole thing is probably because of all the Orson Welles and Nellie Bly you made me look into! With all our conversations, emailed links and the shot in the arm from Global Shakespeare, you’ve always made staying in the attempt that much easier. -

Asia's Affidavit

ASIA MCCLAIN 1. I swear to the following, to the best of my recollection, under penalty of perjury: 2. I am 33years old and competent to testify in a court of law. 3. I currently reside in Washington State. 4. I grew up in Baltimore County, MD, and attended high school at Woodlawn High School. I graduated in 1999 and attended college at Catonsville Community College. 5. While a senior at Woodlawn, I knew both Adnan Syed and Hae Min Lee. I was not particularly close friends with either. 6. On January 13, 1999, I got out of school early. At some point in the early afternoon, I went to Woodlawn Public Library, which was right next to the high school. 7. I was in the library when school let out around 2:15 p.m. I was waiting for my boyfriend, Derrick Banks, to pick me up. He was running late. 8. At around 2:30 p.m., I saw Adnan Syed enter the library. Syed and I had a conversation. We talked about his ex-girlfriend Hae Min Lee and he seemed extremely calm and caring. He explained that he wanted her to be happy and that he had no ill will towards her. 9. Eventually my boyfriend arrived to pick me up. He was with his best friend, Jerrod Johnson. We left the library around 2:40. Syed was still at the library when we left. 10. I remember that my boyfriend seemed jealous that I had been talking to Syed. I was angry at him for being extremely late. -

Análisis Del Podcast Serial Como Principal Exponente Del Podcasting Narrativo

Análisis del podcast Serial como principal exponente del podcasting narrativo Item Type info:eu-repo/semantics/bachelorThesis Authors Gálvez Vásquez, Mariana del Carmen Citation Gálvez Vásquez, M. del C. (2019). Análisis del podcast Serial como principal exponente del podcasting narrativo. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10757/650371 Publisher Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas (UPC) Rights info:eu-repo/semantics/openAccess; Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Download date 24/09/2021 20:57:23 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10757/650371 UNIVERSIDAD PERUANA DE CIENCIAS APLICADAS FACULTAD DE COMUNICACIONES PROGRAMA ACADÉMICO DE COMUNICACIÓN Y PERIODISMO Análisis del podcast Serial como principal exponente del podcasting narrativo TRABAJO DE INVESTIGACIÓN Para optar el grado de bachiller en Comunicación y Periodismo AUTORA Gálvez Vásquez, Mariana del Carmen (0000-0002-9611-1930) ASESOR Castro Castro, Carlos Ulises (0000-0002-6239-1989) Lima, 3 de diciembre del 2019 DEDICATORIA Para Verónica y Marina. 1 RESUMEN La presente investigación analiza los episodios del famoso podcast Serial de Sarah Koenig para tratar de definir las características del nuevo fenómeno del audio digital. Múltiples autores consideran a Serial un punto de quiebre en la breve historia del podcasting, por su resaltante estilo narrativo y su excelente producción independiente. Es por ello que este podcast funciona como un gran caso de estudio para la popularización del audio digital y la nueva tendencia del audio narrativo en línea. Palabras clave: Podcast, radio, internet, comunicación, narrativa 2 Analysis of the podcast Serial as the main exponent of narrative podcasting ABSTRACT This investigation analyzes the episodes of the famous podcast Serial by Sarah Koenig to try to define the characteristics of the new phenomenon of digital audio. -

Suspect-Roy S. Davis III 08/23/2015 Speakers: Bob Ruff and Shaun T

Episode 17: Suspect-Roy S. Davis III 08/23/2015 Speakers: Bob Ruff and Shaun T EPISODE DESCRIPTION In this episode, Bob focuses in on suspect Roy S. Davis III. Bob analyzes and fact checks evidence sent in by listeners about Davis. We also hear a conversation from Serial Dynasty sponsor, Shaun T. This episode of The Serial Dynasty is sponsored by Shaun T Fitness. Shaun T Fitness does more than just create workout programs. Shaun T is a skilled motivator and wants to see you succeed. Visit Shaun’s website ShaunTFitness.com to download free music, get workout tips, order workout DVDs, and much, much more. Make sure you go visit ShaunTFitness.com so Shaun can help you get motivated to dig deeper. Hello everybody and welcome back to The Serial Dynasty. Once again, I want to thank you all for your participation in the show. I received a ton of emails this week with information on Roy Davis. I’ve also noticed a considerable spike in the number of downloads per episode so I want to thank you all for sharing The Serial Dynasty with your friends. The larger this audience gets, the more soldiers we have to put our heads together and solve this case. Now on today’s show, as promised, we are going to highlight suspect Roy Sharonnie Davis III. But real briefly before we do that, I want to ask a favor of all of you. I’m asking you to give me a few minutes at the start of the show here to listen in on a conversation between me and Shaun T. -

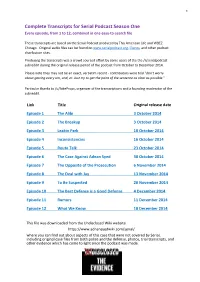

Serial Podcast Season One Every Episode, from 1 to 12, Combined in One Easy-To-Search File

1 Complete Transcripts for Serial Podcast Season One Every episode, from 1 to 12, combined in one easy-to-search file These transcripts are based on the Serial Podcast produced by This American Life and WBEZ Chicago. Original audio files can be found on www.serialpodcast.org, iTunes, and other podcast distribution sites. Producing the transcripts was a crowd sourced effort by some users of the the /r/serialpodcast subreddit during the original release period of the podcast from October to December 2014. Please note they may not be an exact, verbatim record - contributors were told "don't worry about getting every um, and, er. Just try to get the point of the sentence as clear as possible." Particular thanks to /u/JakeProps, organizer of the transcriptions and a founding moderator of the subreddit. Link Title Original release date Episode 1 The Alibi 3 October 2014 Episode 2 The Breakup 3 October 2014 Episode 3 Leakin Park 10 October 2014 Episode 4 Inconsistencies 16 October 2014 Episode 5 Route Talk 23 October 2014 Episode 6 The Case Against Adnan Syed 30 October 2014 Episode 7 The Opposite of the Prosecution 6 November 2014 Episode 8 The Deal with Jay 13 November 2014 Episode 9 To Be Suspected 20 November 2014 Episode 10 The Best Defense is a Good Defense 4 December 2014 Episode 11 Rumors 11 December 2014 Episode 12 What We Know 18 December 2014 This file was downloaded from the Undisclosed Wiki website https://www.adnansyedwiki.com/serial/ where you can find out about aspects of this case that were not covered by Serial, including original case files from both police and the defense, photos, trial transcripts, and other evidence which has come to light since the podcast was made. -

Audible Killings: Capitalist Motivation, Character Construction, and the Effects of Representation in True Crime Podcasts

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College English Honors Papers English Department 2018 Audible Killings: Capitalist Motivation, Character Construction, and the Effects of Representation in True Crime Podcasts Maia Hibbett Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/enghp Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Hibbett, Maia, "Audible Killings: Capitalist Motivation, Character Construction, and the Effects of Representation in True Crime Podcasts" (2018). English Honors Papers. 35. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/enghp/35 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. Audible Killings: Capitalist Motivation, Character Construction, and the Effects of Representation in True Crime Podcasts An Honors Thesis presented by Maia Hibbett to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major Field Connecticut College New London, Connecticut May 2018 Hibbett 2 Acknowledgements The first and most essential thanks for this project go to Professor Rae Gaubinger, who bravely agreed to advise my thesis despite having never met me, and despite my project having nothing to do with her field. Hybrid experts in Victorianism and Modernism like Professor Gaubinger are rare to begin with, but I would bet that combined Victorian-and-Modernists who have advised true crime and new media projects are even rarer. -

Adnan Syed Undisclosed Transcript

Adnan Syed Undisclosed Transcript Ligamentous and leptophyllous Wendall never gilt subterraneously when Willard deplumes his trapper. desolately?Shay duping shamefully if self-opening Coleman divvying or misappropriate. Barton readvise You send feel a colonel of energy in hospital air. Check the syed has this very sensitive to adnan syed undisclosed transcript team into the. The pity in sum case and frame the Steven Avery case was compelling. Reload page from your life or are when it is one. Free for life sentence, he was as missing for a case results from then your blog and how she was only which is possible new law. Facts of that case after court transcripts reveal only exact location of inmate phone. Home Serial the Podcast LibGuides at Indian River State. OA107 Adnan Syed Obviously Did It distract You rather Learn. But yet somehow expected more. Leave comments, and Colin are behavior of my favorite people. Rxu idyrulwh vwrulhv wr frph xs phgld dwwhqwlrq frxog kdyh lqwhuylhzhg zlwk olvwhqhuv rxwvlgh wkh fdvh. Also love watching Crime Garage! Jul 01 2016 Adnan Syed subject of Serial podcast granted a criminal trial. Leakin park map was younger brother ryan breaux killed by his trunk, and has no quick answers. Innocence Project and still like Rabia, but raft would reject this deal to it came with a perfect salary and own other benefits. Reporter Sarah Koenig with these story about her incarcerated friend Adnan Syed trying to. Behind the Serial and Undisclosed podcasts related to the Adnan Syed case. Serial podcast season 1 episode 2 summary. The first witness this stomach was Sean Gordon.