The State of British Business Sunday, November 13, 2011 by Geoff Riley

How well is British business coping in the aftermath of recession and during a sluggish recovery? Are there signs of improvement or are there warning signs that the UK business sector is fragile and vulnerable as we head into 2012? Four AS macro students - James Richardson, Ludo Higgin, Joe Landman and Nick Russell collaborated on this excellent piece and searched for some revealing clues about the resilience of British businesses at this crucial stage of the economic cycle.

In response to underwhelming growth figures for the UK economy as it recovers from the recent recession, the media have begun to report growing fears of a stalling recovery and a likely double-dip recession. The question which remains is whether such concerns are legitimate or not and, in order to answer this, one must assess not only the recovery of corporate giants, but also the health of small UK businesses (referred to as the ‘life-blood of any economy’ by the BBC Business Producer Johny Cassidy) as we head into 2012.

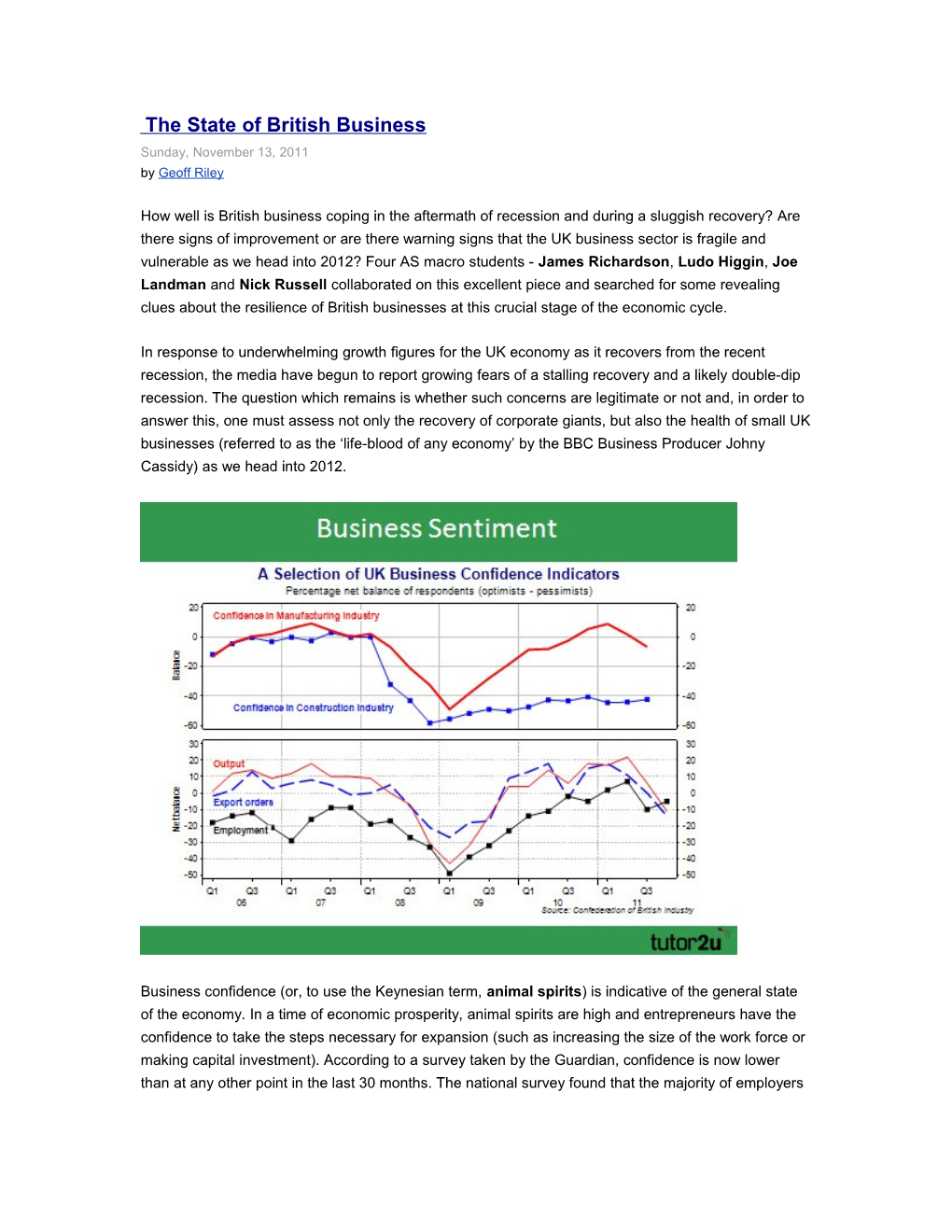

Business confidence (or, to use the Keynesian term, animal spirits) is indicative of the general state of the economy. In a time of economic prosperity, animal spirits are high and entrepreneurs have the confidence to take the steps necessary for expansion (such as increasing the size of the work force or making capital investment). According to a survey taken by the Guardian, confidence is now lower than at any other point in the last 30 months. The national survey found that the majority of employers are wary of expanding too quickly at the moment as they anticipate an unsettled recovery and risk of a double-dip.

A further survey taken in October 2011 on behalf of Lloyds Banking Group claimed that 49% (of the 306 companies which were surveyed) were pessimistic about their prospects in the coming months. This figure had increased from 33% in September 2011, potentially in response to the developing Euro-zone crisis.

If business confidence is as low as these surveys suggest, disappointing figures for capital investment and employment would be expected. Although employment figures are expected to remain low in the coming months, according to career builders, companies such as Asda and Caffe Nero are currently looking to take on new staff. It is likely that the approach of higher-cost brands such as Marks & Spencer and Costa Coffee (normal goods) respectively might be less optimistic, but the figures do suggest at least some signs of improving sentiment in the economy.

And while a fall in the level of capital investment compared to last year would be expected, figures from the Directgov website have a much more optimistic message. According to these figures, business investment in the second quarter of this year had increased by 3.8% compared with the same period in 2010 with total manufacturing rising a massive 22.9% in the last 12 months. The less positive side of this data is that, clearly, investment in certain sectors does not appear to be increasing. Although investment in manufacturing appears to have increased significantly, the service industry, which constitutes a far greater proportion of the UK economy, does not appear to be as confident of economic prospects going forward and so has not invested significantly (hence the overall figure of only 3.8%).

Another factor that must be considered is the availability of finance required to fund sustained expansion (for those businesses that are confident enough to want it). According to data provided by the Bank of England, the stock of lending to businesses by all UK-based banks and building societies contracted by around £2.5 billion in the three months to August. Furthermore, major UK lenders have reported that the quantity of lending by foreign lenders has seen no increase either. While existing businesses are met with tight lending conditions when trying to secure loans, new businesses have little or no chance of securing any kind of funding.

The Government has introduced a scheme called Project Merlin which is designed to make banks lend more and so ease firms’ cash flow problems. The project aims to deliver £76 billion during the year to March 2012. However, many economists believe that such schemes will not suffice and the lack of availability of funding will continue to strangle UK business prospects.

Many UK businesses are reporting disappointing profits. However, there are UK businesses which are managing to continue to develop, expand and deliver profits. According to figures from the Office for National Statistics, in the second quarter of 2011, the net rate of return for Private Non-Financial Corporations was 12.1%. The figure over the same period was 6% for manufacturing companies and 15% for service companies.

Here, the question becomes: how have some businesses managed to maintain or recover profitability? There are some great success stories of UK businesses which have succeeded in bouncing back from the recession strongly and in posting impressive profits. Indeed, RBS, a bank which required a £20 billion bailout from the Government in 2008, recently posted very positive profit figures. By cutting costs, slashing its bad debts and offsetting a plunge in income at its investment arm, RBS announced £2 billion pre-tax profits in the three months to September 2011, compared to a £678 million loss in the previous quarter.

This example goes to show that, despite a lack of business confidence caused by fear of a double-dip and few opportunities to borrow money, it is possible for UK businesses to return to profitability during these difficult times. Indeed, there are many notable success stories, including those of market leaders Tesco and Apple.

Focusing here on the UK, ARM Holdings and Dyson have seen a surge in profit. ARM Holdings, the Cambridge-based world leader in micro-processing, has seen profit rising as demand for technology increases. The company receives royalties for their processors that are outsourced and made by other companies. ARM Holdings produced the Apple A5 processor, which powers iPads and iPhones of today – and is paid a royalty from every product that uses their processors.

ARM only designs, and avoids all overheads by outsourcing. Its business model can be seen as an example to many other UK manufacturing firms: capitalise on intellectual property and industry experience by creating a cutting-edge product and then avoid expensive manufacturing costs in the UK by outsourcing.

A worry for the UK economy continues to be that start-up businesses have a high chance of failing early on – almost 1 in 3 in the UK packs up within three years. Poor marketing, over-borrowing and poor business planning are often blamed for these failures.

According to the Daily Telegraph, the numbers of company failures is at a “two year high”. In the three months to September, the rate of liquidations (where a company is brought to an end and the assets are redistributed) was up by 6.5% at 4,242 closings. This is the highest number since the fourth quarter of 2009. The majority of these failures were in the sectors of business services, hospitality and tourism. Are we heading for a double dip?

Economic growth in the British economy has been minimal since the third quarter of 2010, and small business closures have been on the rise ever since then. With the outlook on the economy bleak, businesses will continue to struggle to maintain price competitiveness and survive, let alone be profitable.

In the past few years, many well-known brands and companies have closed down. In 2011 alone, Habitat, Borders Group and Oddbins have all closed. Borders closed down because its business model wasn’t adaptable to the daily needs of the public – they missed the boat for e-books and when they succumbed to them, they were too late (Amazon had secured the corner of the market). This was particularly damaging when a report surfaced in May 2011 that revealed that Amazon’s e-books outsold their printed books.

Habitat was affected by the lack of demand from its normal customer base (first-time property buyers, students, and other young adults setting up a home) who were severely affected by the recession of 2008. Oddbins was doomed to fail because of a failed long-term plan - the wine store turned to vinegar as the range became bland, and prices were extortionate. The balance of trade can also be seen as a useful indication of the health of the economy and of UK business. The UK is a net importer (more is spent on imports than is earned through exports) and so is said to have a negative trade deficit. Indeed, in 2010, the UK spent around 30% of its GDP on imports and earned around 25% on exports. The importance of the balance of trade becomes clear when one considers that exports are an injection of demand into the economy and imports are a leakage. The total value of UK exports for the 12 months ending June 2010 was £242.5 billion, an increase of £9.3 billion compared to the previous year (a 4% increase).

On the other hand, the total value of UK imports for the 12 months ending June 2010 was £328.3 billion, an increase of £8,282m compared to the previous year (only a 2.6% increase). Although the UK is still a net importer (which has a negative impact on the economy), it is encouraging that exports are increasing faster than imports (and so the trade deficit is diminishing).

Increased levels of exports suggest that the UK is starting to establish itself in the rapid- growing markets of the developing world. However, economists continue to have doubts over the efficiency of UK manufacturing compared to Germany, for example, which is the second largest exporter in the world, by value (NB the success of ARM Holdings in out-sourcing to places where manufacturing costs are lower). Furthermore, some people would argue that it is only the depreciation of the pound against other currencies (in itself an indication of a negative economic situation) which has allowed exports to rise and imports to rise less significantly.

The UK’s highest export earners are machinery, transport, pharmaceuticals (the UK is the third biggest in the sector and contributes 15 of the top 75 best-selling drugs) and weapons (the UK is the second largest producer of weapons). Clearly, the UK excels when it is able to employ high-quality design, engineering and technology to out-shine competitors (whereas China, which has an economy of scale, excels simply by producing at a lower cost than competitors).

Economists also continue to have fears that the UK is struggling to gain market share in booming, developing economies, given that 45% of its exports are shared between the USA, Germany, France, the Netherlands and Ireland. They argue that it will be essential to capitalise on such fast-growing markets if the trade deficit is to be cut in the long run.

Overall, despite the media’s pessimistic portrayal of the current economic situation, there is some evidence of positive business prospects. Plenty of UK companies have managed to adapt to the economic environment by capitalising on consumers’ prudent attitudes, and others whose robust business models have stood them in good stead throughout the downturn, are evidence that profit can be made. However, the majority of the statistics concerning animal spirits, unemployment rates, the availability of money and the rate of closure of businesses do seem to suggest that the UK economy is, at present, stalling in its recovery and is likely to fall into a double-dip recession. While there may be sectors and businesses on a micro-level which have good prospects going forward, the majority of the data suggests, on a macro level, that business prospects going into 2012 are bleak and that the UK as a whole is teetering perilously close to sliding back into recession.