The Form of a Channel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Influence of a Dam on Fine-Sediment Storage in a Canyon River Joseph E

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 111, F01025, doi:10.1029/2004JF000193, 2006 Influence of a dam on fine-sediment storage in a canyon river Joseph E. Hazel Jr.,1 David J. Topping,2 John C. Schmidt,3 and Matt Kaplinski1 Received 24 June 2004; revised 18 August 2005; accepted 14 November 2005; published 28 March 2006. [1] Glen Canyon Dam has caused a fundamental change in the distribution of fine sediment storage in the 99-km reach of the Colorado River in Marble Canyon, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. The two major storage sites for fine sediment (i.e., sand and finer material) in this canyon river are lateral recirculation eddies and the main- channel bed. We use a combination of methods, including direct measurement of sediment storage change, measurements of sediment flux, and comparison of the grain size of sediment found in different storage sites relative to the supply and that in transport, in order to evaluate the change in both the volume and location of sediment storage. The analysis shows that the bed of the main channel was an important storage environment for fine sediment in the predam era. In years of large seasonal accumulation, approximately 50% of the fine sediment supplied to the reach from upstream sources was stored on the main-channel bed. In contrast, sediment budgets constructed for two short-duration, high experimental releases from Glen Canyon Dam indicate that approximately 90% of the sediment discharge from the reach during each release was derived from eddy storage, rather than from sandy deposits on the main-channel bed. -

Biological Impacts of the Elwha River Dams and Potential Salmonid Responses to Dam Removal

George R. Pess1, NOAA Fisheries, Northwest Fisheries Science Center, 2725 Montlake Boulevard East, Seattle, Washington 98112 Michael L. McHenry, Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, 2851 Lower Elwha Road, Port Angeles, Washington 98363 Timothy J. Beechie, and Jeremy Davies, NOAA Fisheries, Northwest Fisheries Science Center, 2725 Montlake Boulevard East, Seattle, Washington 98112 Biological Impacts of the Elwha River Dams and Potential Salmonid Responses to Dam Removal Abstract The Elwha River dams have disconnected the upper and lower Elwha watershed for over 94 years. This has disrupted salmon migration and reduced salmon habitat by 90%. Several historical salmonid populations have been extirpated, and remaining popu- lations are dramatically smaller than estimated historical population size. Dam removal will reconnect upstream habitats which will increase salmonid carrying capacity, and allow the downstream movement of sediment and wood leading to long-term aquatic habitat improvements. We hypothesize that salmonids will respond to the dam removal by establishing persistent, self-sustaining populations above the dams within one to two generations. We collected data on the impacts of the Elwha River dams on salmonid populations and developed predictions of species-specific response dam removal. Coho (Oncorhynchus kisutch), Chinook (O. tshawytscha), and steelhead (O. mykiss) will exhibit the greatest spatial extent due to their initial population size, timing, ability to maneuver past natural barriers, and propensity to utilize the reopened alluvial valleys. Populations of pink (O. gorbuscha), chum (O. keta), and sockeye (O. nerka) salmon will follow in extent and timing because of smaller extant populations below the dams. The initially high sediment loads will increase stray rates from the Elwha and cause deleterious effects in the egg to outmigrant fry stage for all species. -

Geomorphic Classification of Rivers

9.36 Geomorphic Classification of Rivers JM Buffington, U.S. Forest Service, Boise, ID, USA DR Montgomery, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA Published by Elsevier Inc. 9.36.1 Introduction 730 9.36.2 Purpose of Classification 730 9.36.3 Types of Channel Classification 731 9.36.3.1 Stream Order 731 9.36.3.2 Process Domains 732 9.36.3.3 Channel Pattern 732 9.36.3.4 Channel–Floodplain Interactions 735 9.36.3.5 Bed Material and Mobility 737 9.36.3.6 Channel Units 739 9.36.3.7 Hierarchical Classifications 739 9.36.3.8 Statistical Classifications 745 9.36.4 Use and Compatibility of Channel Classifications 745 9.36.5 The Rise and Fall of Classifications: Why Are Some Channel Classifications More Used Than Others? 747 9.36.6 Future Needs and Directions 753 9.36.6.1 Standardization and Sample Size 753 9.36.6.2 Remote Sensing 754 9.36.7 Conclusion 755 Acknowledgements 756 References 756 Appendix 762 9.36.1 Introduction 9.36.2 Purpose of Classification Over the last several decades, environmental legislation and a A basic tenet in geomorphology is that ‘form implies process.’As growing awareness of historical human disturbance to rivers such, numerous geomorphic classifications have been de- worldwide (Schumm, 1977; Collins et al., 2003; Surian and veloped for landscapes (Davis, 1899), hillslopes (Varnes, 1958), Rinaldi, 2003; Nilsson et al., 2005; Chin, 2006; Walter and and rivers (Section 9.36.3). The form–process paradigm is a Merritts, 2008) have fostered unprecedented collaboration potentially powerful tool for conducting quantitative geo- among scientists, land managers, and stakeholders to better morphic investigations. -

Trip Planner

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon, Arizona Trip Planner Table of Contents WELCOME TO GRAND CANYON ................... 2 GENERAL INFORMATION ............................... 3 GETTING TO GRAND CANYON ...................... 4 WEATHER ........................................................ 5 SOUTH RIM ..................................................... 6 SOUTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 7 NORTH RIM ..................................................... 8 NORTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 9 TOURS AND TRIPS .......................................... 10 HIKING MAP ................................................... 12 DAY HIKING .................................................... 13 HIKING TIPS .................................................... 14 BACKPACKING ................................................ 15 GET INVOLVED ................................................ 17 OUTSIDE THE NATIONAL PARK ..................... 18 PARK PARTNERS ............................................. 19 Navigating Trip Planner This document uses links to ease navigation. A box around a word or website indicates a link. Welcome to Grand Canyon Welcome to Grand Canyon National Park! For many, a visit to Grand Canyon is a once in a lifetime opportunity and we hope you find the following pages useful for trip planning. Whether your first visit or your tenth, this planner can help you design the trip of your dreams. As we welcome over 6 million visitors a year to Grand Canyon, your -

Timescale Dependence in River Channel Migration Measurements

TIMESCALE DEPENDENCE IN RIVER CHANNEL MIGRATION MEASUREMENTS Abstract: Accurately measuring river meander migration over time is critical for sediment budgets and understanding how rivers respond to changes in hydrology or sediment supply. However, estimates of meander migration rates or streambank contributions to sediment budgets using repeat aerial imagery, maps, or topographic data will be underestimated without proper accounting for channel reversal. Furthermore, comparing channel planform adjustment measured over dissimilar timescales are biased because shortand long-term measurements are disproportionately affected by temporary rate variability, long-term hiatuses, and channel reversals. We evaluate the role of timescale dependence for the Root River, a single threaded meandering sand- and gravel-bedded river in southeastern Minnesota, USA, with 76 years of aerial photographs spanning an era of landscape changes that have drastically altered flows. Empirical data and results from a statistical river migration model both confirm a temporal measurement-scale dependence, illustrated by systematic underestimations (2–15% at 50 years) and convergence of migration rates measured over sufficiently long timescales (> 40 years). Frequency of channel reversals exerts primary control on measurement bias for longer time intervals by erasing the record of observable migration. We conclude that using long-term measurements of channel migration for sediment remobilization projections, streambank contributions to sediment budgets, sediment flux estimates, and perceptions of fluvial change will necessarily underestimate such calculations. Introduction Fundamental concepts and motivations Measuring river meander migration rates from historical aerial images is useful for developing a predictive understanding of channel and floodplain evolution (Lauer & Parker, 2008; Crosato, 2009; Braudrick et al., 2009; Parker et al., 2011), bedrock incision and strath terrace formation (C. -

XS1 Riffle STA 0+27 Ground Points Bankfull Indicators Water Surface Points Wbkf = 26.9 Dbkf = 1.46 Abkf = 39.4 105

XS1 Riffle STA 0+27 Ground Points Bankfull Indicators Water Surface Points Wbkf = 26.9 Dbkf = 1.46 Abkf = 39.4 105 100 Elevation (ft) 95 90 0 102030405060 Horizontal Distance (ft) Team 1 Riffle STA 133 Ground Points Bankfull Indicators Water Surface Points Wbkf = 23.4 Dbkf = 1.48 Abkf = 34.6 105 100 Elevation (ft) 95 90 0 1020304050 Horizontal Distance (ft) XS3 Lateral Scour Pool STA 0+80.9 Ground Points Bankfull Indicators Water Surface Points Inner Berm Indicators Wbkf = 25.9 Dbkf = 1.73 Abkf = 44.7 105 Wib = 14 Dib = .93 Aib = 13.1 Elevation (ft) 90 0 90 Horizontal Distance (ft) Team 1 Lateral Scour Pool STA 211 Ground Points Bankfull Indicators Water Surface Points Inner Berm Indicators Wbkf = 26.8 Dbkf = 1.86 Abkf = 49.7 105 Wib = 15.2 Dib = .91 Aib = 13.7 100 Elevation (ft) 95 90 0 1020304050 Horizontal Distance (ft) XS2 Run STA 0+44.1 Ground Points Bankfull Indicators Water Surface Points Wbkf = 22.6 Dbkf = 1.96 Abkf = 44.4 105 100 Elevation (ft) 95 90 0 102030405060 Horizontal Distance (ft) Team 1 Run STA 151 Ground Points Bankfull Indicators Water Surface Points Wbkf = 24.2 Dbkf = 1.69 Abkf = 40.9 105 100 Elevation (ft) 95 90 0 1020304050 Horizontal Distance (ft) XS4 Glide STA 104.2 Ground Points Bankfull Indicators Water Surface Points Wbkf = 25.9 Dbkf = 1.62 Abkf = 42 106 Elevation (ft) 95 0 70 Horizontal Distance (ft) Team 1 Glide STA 236 Ground Points Bankfull Indicators Water Surface Points Inner Berm Indicators Wbkf = 20.8 Dbkf = 1.75 Abkf = 36.3 105 Wib = 15.7 Dib = .85 Aib = 13.3 100 Elevation (ft) 95 90 0 1020304050 -

Stream Restoration, a Natural Channel Design

Stream Restoration Prep8AICI by the North Carolina Stream Restonltlon Institute and North Carolina Sea Grant INC STATE UNIVERSITY I North Carolina State University and North Carolina A&T State University commit themselves to positive action to secure equal opportunity regardless of race, color, creed, national origin, religion, sex, age or disability. In addition, the two Universities welcome all persons without regard to sexual orientation. Contents Introduction to Fluvial Processes 1 Stream Assessment and Survey Procedures 2 Rosgen Stream-Classification Systems/ Channel Assessment and Validation Procedures 3 Bankfull Verification and Gage Station Analyses 4 Priority Options for Restoring Incised Streams 5 Reference Reach Survey 6 Design Procedures 7 Structures 8 Vegetation Stabilization and Riparian-Buffer Re-establishment 9 Erosion and Sediment-Control Plan 10 Flood Studies 11 Restoration Evaluation and Monitoring 12 References and Resources 13 Appendices Preface Streams and rivers serve many purposes, including water supply, The authors would like to thank the following people for reviewing wildlife habitat, energy generation, transportation and recreation. the document: A stream is a dynamic, complex system that includes not only Micky Clemmons the active channel but also the floodplain and the vegetation Rockie English, Ph.D. along its edges. A natural stream system remains stable while Chris Estes transporting a wide range of flows and sediment produced in its Angela Jessup, P.E. watershed, maintaining a state of "dynamic equilibrium." When Joseph Mickey changes to the channel, floodplain, vegetation, flow or sediment David Penrose supply significantly affect this equilibrium, the stream may Todd St. John become unstable and start adjusting toward a new equilibrium state. -

Logistic Analysis of Channel Pattern Thresholds: Meandering, Braiding, and Incising

Geomorphology 38Ž. 2001 281–300 www.elsevier.nlrlocatergeomorph Logistic analysis of channel pattern thresholds: meandering, braiding, and incising Brian P. Bledsoe), Chester C. Watson 1 Department of CiÕil Engineering, Colorado State UniÕersity, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA Received 22 April 2000; received in revised form 10 October 2000; accepted 8 November 2000 Abstract A large and geographically diverse data set consisting of meandering, braiding, incising, and post-incision equilibrium streams was used in conjunction with logistic regression analysis to develop a probabilistic approach to predicting thresholds of channel pattern and instability. An energy-based index was developed for estimating the risk of channel instability associated with specific stream power relative to sedimentary characteristics. The strong significance of the 74 statistical models examined suggests that logistic regression analysis is an appropriate and effective technique for associating basic hydraulic data with various channel forms. The probabilistic diagrams resulting from these analyses depict a more realistic assessment of the uncertainty associated with previously identified thresholds of channel form and instability and provide a means of gauging channel sensitivity to changes in controlling variables. q 2001 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Channel stability; Braiding; Incision; Stream power; Logistic regression 1. Introduction loads, loss of riparian habitat because of stream bank erosion, and changes in the predictability and vari- Excess stream power may result in a transition ability of flow and sediment transport characteristics from a meandering channel to a braiding or incising relative to aquatic life cyclesŽ. Waters, 1995 . In channel that is characteristically unstableŽ Schumm, addition, braiding and incising channels frequently 1977; Werritty, 1997. -

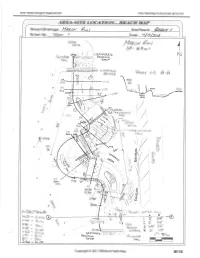

Iron Canyon Watershed.···,· "'

Preface This Watershed Analysis is presented as ·part of the Aquatic Conservation Str:9-tegy adopted for the President's Plan (Record of Decision for Amendments to Forest Service and.Bureau ofLand Management Planning Documents within the R'ang'e of the Northern Spotted Owl, including Standards and Guidelines for Management of Habitat for Late-Succ~ssional ,and Old-Growth Related Species). .,'.. ·:., ·.. ·. .•.·.· . Announcements were published in local newspapers in ReddinP; and ~~.ni.them Si~,kjyou C,ounty inviting public input to this analysis. Open Houses were held ill Reddirig,' 11c.Cloud ahd,Big ·J3end,"\vhere resource specialists presented information on existing conditions and manag~ment direction for National Forestlands within the Iron Canyon Watershed.···,· "': The Iron Canyon Watershed Analysis was prepared with input and irivolvement from the following resource specialists: · ' · ..., .. o - . Charles Miller Forester/Team Leader . .i McCloud Ranger District Nancy Hutchins · Wildlife Biologist· : · · : · Shasta Lake Ranger District Bill Brock Fisheries Biologist .U.S.Fish and Wildlife Service Becky May Fire Management Officer · Shasta I:.ake Ranger District Rhonda Posey · · Ecologist Shasta Lake Ranger District Chuck McDonald SilViculturist Mount Shasta Ranger District Abel Jasso Geologist Shasta take Ranger District Ken Lanspa Soil Scientist Shasta,-.. Trinity National Forests Norman Braithwaite Hydrologist ·North State Resources Joe Zustak · .. Fisheries Biologist . · Shasta Lake Ranger District JeffHuhtala Engineering Technician. · Moimt Shasta Ranger District Paula ·crumpton . .. Wildlife Biologist/Teairi Cmich . ··shasta-Tpnity National Forests Dave Simons Writer/Editor McCloud Ranger District Additional input was provided by: Elaine Sundahl Archaeologist . Shasta Lake Ranger District Mary Ellen Grigsby Recreation Specialist · ·· ·shaSta Lak~ Ranger District Jonna Cooper · · Geographic Inforrilati9n:Systems McCloud Ra~gerDistrict · . -

Channel Morphology and Bedrock River Incision: Theory, Experiments, and Application to the Eastern Himalaya

Channel morphology and bedrock river incision: Theory, experiments, and application to the eastern Himalaya Noah J. Finnegan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2007 Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Earth and Space Sciences University of Washington Graduate School This is to certify that I have examined this copy of a doctoral dissertation by Noah J. Finnegan and have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: ___________________________________________________________ Bernard Hallet ___________________________________________________________ David R. Montgomery Reading Committee: ____________________________________________________________ Bernard Hallet ____________________________________________________________ David R. Montgomery ____________________________________________________________ Gerard Roe Date:________________________ In presenting this dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the doctoral degree at the University of Washington, I agree that the Library shall make its copies freely available for inspection. I further agree that extensive copying of the dissertation is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for copying or reproduction of this dissertation may be referred -

Hells Canyon 5 Day to Heller

Trip Logistics and Itinerary 5 days, 4 nights Wine & Food on the Snake River in Hells Canyon Trip Starts: Minam, OR Trip Ends: Minam, OR Put-in: Hell’s Canyon Dam, OR Take-out: Heller Bar, WA (23 miles south of Asotin, WA) Trip length: 79 miles Class III-IV rapids Each Trip varies slightly with size of group, interests of guests, etc. This is a “typical” trip itinerary that will vary. Day before Launch: Stop at Minam on your way to your motel in Wallowa or Enterprise to pick up your dry bag and go over the morning itinerary. Day 1: If staying in Wallowa at the Mingo Motel we will pick you up at 6:15 am. If staying in Enterprise we will pick you up at the Ponderosa Motel in our shuttle van at 6:45 am. Travel to Hells Canyon Dam Launch site (3hr drive from Minam) with a bathroom break at the Hells Canyon Overlook. Meet your guides, go over basic safety talk, and load into rafts between 10 and 11 am. Lunch will be served riverside. Enjoy awe inspiring geology, spot wildlife. Run some of the biggest whitewater of the trip, first up Wild Sheep Rapid. Stop to scout Granite Rapid and view Nez Perce pictographs. Arrive in camp between 3-4pm. Evening camp time: swim, hike, play games, relax! Approximately 6pm: Wine and Hor D’oevres presented by Chef Andrae and the featured Winery. Approximately 7 pm dinner presented by chef Andrae Bopp. Day 2: Coffee is ready by 6 am. Leisurely breakfast between 7 and 8 am. -

River Incision Into Bedrock: Mechanics and Relative Efficacy of Plucking, Abrasion and Cavitation

River incision into bedrock: Mechanics and relative efficacy of plucking, abrasion and cavitation Kelin X. Whipple* Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Gregory S. Hancock Department of Geology, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia 23187 Robert S. Anderson Department of Earth Sciences, University of California, Santa Cruz, California 95064 ABSTRACT long term (Howard et al., 1994). These conditions are commonly met in Improved formulation of bedrock erosion laws requires knowledge mountainous and tectonically active landscapes, and bedrock channels are of the actual processes operative at the bed. We present qualitative field known to dominate steeplands drainage networks (e.g., Wohl, 1993; Mont- evidence from a wide range of settings that the relative efficacy of the gomery et al., 1996; Hovius et al., 1997). As the three-dimensional structure various processes of fluvial erosion (e.g., plucking, abrasion, cavitation, of drainage networks sets much of the form of terrestrial landscapes, it is solution) is a strong function of substrate lithology, and that joint spac- clear that a deep appreciation of mountainous landscapes requires knowl- ing, fractures, and bedding planes exert the most direct control. The edge of the controls on bedrock channel morphology. Moreover, bedrock relative importance of the various processes and the nature of the in- channels play a critical role in the dynamic evolution of mountainous land- terplay between them are inferred from detailed observations of the scapes (Anderson, 1994; Anderson et al., 1994; Howard et al., 1994; Tucker morphology of erosional forms on channel bed and banks, and their and Slingerland, 1996; Sklar and Dietrich, 1998; Whipple and Tucker, spatial distributions.