Ciara Healy Thin Place Phd Thesis for Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Diary of a West Country Physician, A.D. 1684-1726

Al vi r 22101129818 c Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Wellcome Library https://archive.org/details/b31350914 THE DIARY OF A WEST COUNTRY PHYSICIAN IS A Obi,OJhJf ct; t k 9 5 *fay*/'ckf f?c<uz.s <L<rble> \\M At—r J fF—ojILlIJ- y 't ,-J.M- * - ^jy,-<9. QjlJXy }() * |L Crf fitcJlG-t t $ <z_iedl{£ AU^fytsljc<z.^ act Jfi :tnitutor clout % f §Ve* dtrrt* 7. 5^at~ frt'cUt «k ^—. ^LjHr£hur IW*' ^ (9 % . ' ' ?‘ / ^ f rf i '* '*.<,* £-#**** AT*-/ ^- fr?0- I&Jcsmjl. iLM^i M/n. Jstn**tvn- A-f _g, # ««~Hn^ &"<y muy/*£ ^<u j " *-/&**"-*-■ Ucn^f 3:Jl-y fi//.XeKih>■^':^. li M^^atUu jjm.(rmHjf itftLk*P*~$y Vzmltti£‘tortSctcftuuftriftmu ■i M: Oxhr£fr*fro^^^ J^lJt^ veryf^Jif b^ahtw-* ft^T #. 5£)- (2) rteui *&• ^ y&klL tn £lzJ£xH*AL% S. HjL <y^tdn %^ cfAiAtL- Xp )L ^ 9 $ <£t**$ufl/ Jcjz^, JVJZuil ftjtij ltf{l~ ft Jk^Hdli^hr^ tfitre , f cc»t<L C^i M hrU at &W*&r* &. ^ H <Wt. % fit) - 0 * Cff. yhf£ fdtr tj jfoinJP&*Ji t/ <S m-£&rA tun 9~& /nsJc &J<ztt r£$tr*kt.bJtVYTU( Hr^JtcAjy£,, $ev£%y£ t£* tnjJuk^ THE DIARY OF A WEST COUNTRY PHYSICIAN A.D. 1684-1726 Edited by EDMUND HOBHOUSE, M.D. ‘Medicines ac Musarum Cultor9 TRADE AGENTS: SIMPKIN MARSHALL, LTD. Stationers’ Hall Court, London, E.C.4 PRINTED BY THE STANHOPE PRESS, ROCHESTER *934 - v- p C f, ,s*j FOREWORD The Manuscripts which furnish the material for these pages consist of four large, vellum-bound volumes of the ledger type, which were found by Mr. -

Saints, Monks and Bishops; Cult and Authority in the Diocese of Wells (England) Before the Norman Conquest

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 3 Issue 2 63-95 2011 Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest Michael Costen University of Bristol Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Costen, Michael. "Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 3, 2 (2011): 63-95. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol3/iss2/4 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Costen Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest Michael Costen, University of Bristol, UK Introduction This paper is founded upon a database, assembled by the writer, of some 3300 instances of dedications to saints and of other cult objects in the Diocese of Bath and Wells. The database makes it possible to order references to an object in many ways including in terms of dedication, location, date, and possible authenticity, and it makes data available to derive some history of the object in order to assess the reliability of the information it presents. -

Minutes of the Annual Parish Meeting of Butleigh Parish Council Held at 7.00P.M

MINUTES OF THE ANNUAL PARISH MEETING OF BUTLEIGH PARISH COUNCIL HELD AT 7.00P.M. ON 5 th April 2016 IN THE CHURCH ROOM, BUTLEIGH. PARISH COUNCILLORS PRESENT: A Carr (Chairman), K Otton, W Moore-Read, APOLOGIES : Richard Burdett, E Aitken OTHERS PRESENT: M Hoyle, T Hoyle, T Done, G de Wilton, S de Camp, N Woolcombe- Adams, Mrs C Simpson . CHAIRMAN’S REPORT; ALAN CARR REPORTED: Welcome to the Annual Parish Meeting. This meeting gives Parishioners a chance to hear what the Parish Council has been doing on their behalf during the year and raise any questions. Council Meetings Unfortunately this year the Council has been operating with less than its full compliment of Councillors. Currently there are 5 Councillors instead of 8. So far attempts to recruit have been unsuccessful. Meetings are usually held on the first Tuesday of the month and the dates are published in advance on the Parish Noticeboard and in News and Views. There has been an 82% councillor attendance over 10 meetings. Our County and District Ward Councillor Nigel Woollcombe-Adams has attended on 3 occasions during the year. When contentious planning applications have been on the agenda a number of villagers have attended but generally public attendance has been limited. Councillors have attended training sessions in Shepton Mallet when appropriate. Planning As a Public Consultee the Parish Council looked at 30 applications. We recommended 23 for approval and 3 for refusal. Mendip District Council approved 22 and refused 1 of these. The balance were either withdrawn or are awaiting decisions. There have been a number of Planning Appeals. -

Notice of Poll

SOMERSET COUNTY COUNCIL ELECTION OF A COUNTY COUNCILLOR FROME EAST DIVISION NOTICE OF POLL Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of A COUNTY COUNCILLOR for the FROME EAST DIVISION will be held on THURSDAY 4 MAY 2017, between the hours of 7:00 AM and 10:00 PM 2. The names, addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated and the names of all the persons signing the Candidates nomination papers are as follows: Name of Candidate Address Description Names of Persons who have signed the Nomination Paper Eve 9 Whitestone Road The Conservative J M Harris M Bristow BERRY Frome Party Candidate B Harris P Bristow Somerset Kelvin Lum V Starr BA11 2DN Jennifer J Lum S L Pomeroy J Bristow J A Bowers Martin John Briars Green Party G Collinson Andrew J Carpenter DIMERY Innox Hill K Harley R Waller Frome J White T Waller Somerset M Wride M E Phillips BA11 2LW E Carpenter J Thomas Alvin John 1 Hillside House Liberal Democrats A Eyers C E Potter HORSFALL Keyford K M P Rhodes A Boyden Frome Deborah J Webster S Hillman BA11 1LB J P Grylls T Eames A J Shingler J Lewis David Alan 35 Alexandra Road Labour Party William Lowe Barry Cooper OAKENSEN Frome Jean Lowe R Burnett Somerset M R Cox Karen Burnett BA11 1LX K A Cooper A R Howard S Norwood J Singer 3. The situation of the Polling Stations for the above election and the Local Government electors entitled to vote are as follows: Description of Persons entitled to Vote Situation of Polling Stations Polling Station No Local Government Electors whose names appear on the Register of Electors for the said Electoral Area for the current year. -

New Slinky Mendip West L/Let.Indd 1 20/01/2017 14:54 Monday Pickup Area Tuesday Pickup Area Wednesday Pickup Area

What is the Slinky? How much does it cost? Slinky is an accessible bus service funded Please phone the booking office to check Mendip West Slinky by Somerset County Council for people the cost for your journey. English National unable to access conventional transport. Concessionary Travel Scheme passes can be Your local transport service used on Slinky services. You will need to show This service can be used for a variety of your pass every time you travel. Somerset reasons such as getting to local health Student County Tickets are also valid on appointments or exercise classes, visiting Slinky services. friends and relatives, going shopping or for social reasons. You can also use the Slinky Somerset County Council’s Slinky Service is as a link to other forms of public transport. operated by: Mendip Community Transport, MCT House, Who can use the Slinky? Unit 10a, Quarry Way Business Park, You will be eligible to use the Slinky bus Waterlip, Shepton Mallet, Somerset BA4 4RN if you: [email protected] • Do not have your own transport www.mendipcommunitytransport.co.uk • Do not have access to a public bus service • Or have a disability which means you Services available: cannot access a public bus Monday to Friday excluding Public Holidays Parents with young children, teenagers, students, the elderly, the retired and people Booking number: with disabilities could all be eligible to use the Slinky bus service. 01749 880482 Booking lines are open: How does it work? Monday to Friday 9.30am to 4pm If you are eligible to use the service you will For more information on Community first need to register to become a member of Transport in your area, the scheme. -

Butleigh Parish Housing Needs Survey

Butleigh Parish (including Butleigh Wootton) Housing Needs Survey Conducted by The Community Council for Somerset 6 March 2017 Telephone 01823 331222 I Email [email protected] I www.somersertrcc.org.uk Community Council for Somerset, Victoria House, Victoria Street, Taunton TA1 3JZ The Community Council for Somerset is a Company Limited by Guarantee, Registered in England & Wales No. 3541219, and is a Registered Charity No. 1069260 © 2017 This report, or any part, may be reproduced in any format or medium, provided that is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The source must be identified and the title of the publication specified with the copyright status acknowledged. Contents Introduction 1 Aims, Methodology, Presentation and Interpretation of Data 2 Summary 3-5 Findings 6-22 Respondent profile 6-8 Overview of housing needs and development in Butleigh 9-11 Site features and proposed dwellings for any proposed development sites in Butleigh 11-13 New open market housing 14-16 Housing for older people 16-20 Additional comments (see Appendix 2) 20 Affordable housing summary 21-22 Appendices Appendix 1: Questionnaire Appendix 2: Verbatim comments Appendix 3: Full Survey Results Summary Tables Appendix 4: Respondent Profile Affordable Housing [access restricted to CCS and MDC employees] Tables Table 1 Typical property and rental levels (cheapest 25%) for Butleigh Parish and surrounding area 1 Table 2 Affordable housing (11 respondents) 22 Charts Chart 1 Gender 6 Chart 2 Parish residency status 6 Chart 3 2nd property -

Statutory Consultees and Agencies

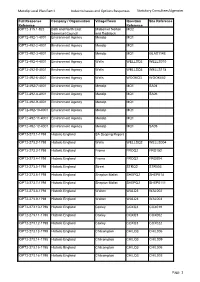

Mendip Local Plan Part II Index to Issues and Options Responses Statutory Consultees/Agencies Full Response Company / Organisation Village/Town Question Site Reference Reference Reference IOPT2-315.1-823 Bath and North East Midsomer Norton MQ2 Somerset Council and Radstock IOPT2-492-1-4001 Environment Agency Mendip MQ1 IOPT2-492-2-4001 Environment Agency Mendip MQ1 IOPT2-492-3-4001 Environment Agency Mendip MQ1 GLAS114E IOPT2-492-4-4001 Environment Agency Wells WELLSQ3 WELLS010 IOPT2-492-5-4001 Environment Agency Wells WELLSQ3 WELLS118 IOPT2-492-6-4001 Environment Agency Wells WOOKQ3 WOOK002 IOPT2-492-7-4001 Environment Agency Mendip MQ1 SA04 IOPT2-492-8-4001 Environment Agency Mendip MQ1 SA06 IOPT2-492-9-4001 Environment Agency Mendip MQ1 IOPT2-492-10-4001 Environment Agency Mendip MQ1 IOPT2-492-11-4001 Environment Agency Mendip MQ1 IOPT2-492-12-4001 Environment Agency Mendip MQ1 SA05 IOPT2-273.1-1798 Historic England SA Scoping Report IOPT2-273.2-1798 Historic England Wells WELLSQ2 WELLS004 IOPT2-273.3-1798 Historic England Frome FROQ2 FRO152 IOPT2-273.4-1798 Historic England Frome FROQ2 FRO004 IOPT2-273.5-1798 Historic England Street STRQ2 STR003 IOPT2-273.6-1798 Historic England Shepton Mallet SHEPQ2 SHEP014 IOPT2-273.7-1798 Historic England Shepton Mallet SHEPQ2 SHEP0111 IOPT2-273.8-1798 Historic England Walton WALQ3 WAL002 IOPT2-273.9-1798 Historic England Walton WALQ3 WAL003 IOPT2-273.10-1798 Historic England Coxley COXQ3 COX019 IOPT2-273.11-1798 Historic England Coxley COXQ3 COX002 IOPT2-273.12-1798 Historic England Coxley COXQ3 -

Mendip District Council Draft Local Plan 2006-2028

MENDIP DISTRICT LOCAL PLAN 2006-2028 PART I: STRATEGY AND POLICIES Formerly known as the Local Development Framework Core Strategy DRAFT PLAN FOR CONSULTATION (Pre-Submission Stage) CONSULTATION PERIOD th th 29 November 2012 – 24 January 2013 “TIME TO PLAN” MENDIP DISTRICT LOCAL PLAN 2006-2028 – Pre-Submission Draft (November 2012) CONTENTS What is this document for ? iii Giving us your views v 1.0 Introduction 1 The Local Plan 1 The context within which we plan 4 “Time To Plan” – The Preparation of the Local Plan 6 Delivery and Monitoring 8 Status of Policies and Supporting Text 8 2.0 A Portrait of Mendip 9 Issues facing the District 9 Summary 20 3.0 A Vision for Mendip 23 A Vision of Mendip District In 2028 23 Strategic Objectives Of The Mendip Local Plan 24 4.0 Spatial Strategy 27 Core Policy 1 : Mendip Settlement Strategy 27 Core Policy 2 : Supporting the Provision of New Housing 33 Core Policy 3 : Supporting Business Development and Growth 40 Core Policy 4 : Sustaining Rural Communities 45 Core Policy 5 : Encouraging Community Leadership 48 5.0 Town Strategies 51 Core Policy 6 : Frome 52 Core Policy 7: Glastonbury 59 Core Policy 8 : Street 63 Core Policy 9 : Shepton Mallet 67 Core Policy 10 : Wells 73 6.0 Local Development Policies 81 National Planning Policies and the Local Plan 81 Protecting Mendip’s Distinctive Character and Promoting Better Development 83 Development Policies 1-10 Providing Places To Live 102 Development Policies 11-15 Local Infrastructure 114 Development Policies 16-19 Maintaining Economic Potential 121 Development -

JRA Volume 111 Issue 2 Cover and Back Matter

ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY OF GREAT BRITAIN & IRELAND (FOUNDED MARCH, 1823) LIST OF FELLOWS, LIBRARY ASSOCIATES AND SUBSCRIBERS 1979 PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY 56 QUEEN ANNE STREET LONDON W1M 9LA Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.35.229, on 28 Sep 2021 at 11:09:51, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0035869X00135518 56 QUEEN ANNE STREET, LONDON, W1M 9LA (Tel: 01-935 8944) Patron HER MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY THE QUEEN Vice-Patron HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCE OF WALES Honorary Vice-Presidents 1963 PROFESSOR SIR RALPH L. TURNER, MC 1976 PROFESSOR SIR HAROLD BAILEY 1976 PROFESSOR E. J. W. SIMON, CBE COUNCIL OF MANAGEMENT FOR 1979-80 President 1979 PROFESSOR SIR CYRIL PHILIPS Director 1977 MR D. J. DUNCANSON, OBE Vice-Presidents 1976 PROFESSOR E. H. S. SIMMONDS 1977 PROFESSOR K. A. BALLHATCHET 1978 MR E. P. SOUTHALL 1979 PROFESSOR C. F. BECKINGHAM Honorary Officers 1978 MR G. A. CALVER (Hon. Treasurer) 1977 MR N. M. LOWICK (Hon. Secretary) 1971 MR S. E. DIGBY (Hon. Librarian) 1979 DR A. D. H. BIVAR (Hon. Editor) Ordinary Members of Council 1978 MAJOR J. E. BARWIS-HOLLIDAY 1976 MR A. S. BENNELL 1979 MR R. M. BURRELL 1976 MR J. BURTON-PAGE 1979 MR A. H. CHRISTIE 1976 PROFESSOR C. J. DUNN 1977 MR J. F. FORD.CMG, OBE 1978 MR F. G. GOODWIN 1979 DR M. A. N. LOEWE 1976 MR P. S. MARSHALL 1979 PROFESSOR V. L. MENAGE 1977 MR B.W. -

MINUTES of the MEETING of BUTLEIGH PARISH COUNCIL HELD on TUESDAY 3 Rd January 2017 in the CHURCH ROOM, BUTLEIGH

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF BUTLEIGH PARISH COUNCIL HELD ON TUESDAY 3 rd January 2017 IN THE CHURCH ROOM, BUTLEIGH. PARISH COUNCILLORS PRESENT : A Carr, (Chairman). K Otton, W Moore-Read. R Burdett, R Davidson. OTHERS PRESENT : Heather Colman (Village Agent CCS) – Pre- Meeting explained her role as Village Agent, Mr & Mrs T Hoyle. APOLOGIES: E Aitken. STATEMENT OF DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST : The Chairman reminded Councillors of the need to make and to have recorded any Declarations of Interest made in accordance with the Local Authorities Model Code of Conduct Order adopted on 7th August 2012. (Based on District/ County Model ) (Chapter 7 of the Localism Act 2011). R Davidson Prejudicial interest in Local Plan Part 2 URGENT BUSINESS : Local Plan Part 2- Informal Consultation. Plan of preferred sites, green spaces plan and list of playing fields. Comments due by the end of January. A Carr proposed sending a response as discussed. Seconded R Burdett, all in favour. MINUTES OF THE MEETING HELD ON 6 th December 2016, having been circulated, were signed as a true and correct record. Proposed R Burdett, seconded R Davidson, all in favour. MATTERS ARISING : None PLANNING . 2016/2882/HSE Copperfield, Barton Road – Kitchen extension, new porch, creation of a garden room, sundry alterations. Recommend Approval, Proposed W Moore-Read, seconded A Carr. All in favour. DECISIONS: 2016/2635/HSE The Sweets, Chapel Lane - Proposed single storey extension and internal alterations- Approved 2016/2783/TPO 5 Mounsdon Close- Sallow Tree fell – TPO not required 2016/2304/HSE 2 Compton Street- Proposed demolitions, rear and side extension and loft conversion- Approved. -

Travelling to Strode College from Yeovil, Gillingham and Alhampton

TRAVELLING TO STRODE COLLEGE FROM YEOVIL, GILLINGHAM AND ALHAMPTON Town Route or 667 Alford 647 Kingsdon 77 East Pennard Baltonsborough 647 Langport 55C Strode College West Bradley Barton St David 667 Lovington 647/667 Street 667 Slinky 1/647/667 Baltonsborough Ditcheat Bruton Bourton 647 Lydford on Fosse 647/667 Ham Alhampton Street Bruton 646 Marshalls Elm 77 667 Alford 646 Compton Butleigh Castle Cary 646 Butleigh 667 Marston Magna 1 (647/667) Dundon 647/667 Barton Lydford Butleigh Wootton 647/667 Milborne Port 646 St David Lovington 647 77 1/647/667 1 Burton Castle Cary 647/667 Mudford 1 (647/667) Keinton 647 55C Mandeville Galhampton Charlton Horethorne 646 North Cadbury 1 (647/667) Charlton Wincanton Mackerell 647 Charlton Mackrell 77 Peacemarsh 647 Somerton Sparkford North 646 Compton Dundon 77/55C Pitney 55C or 652 Kingsdon 1 Cadbury Curry Rival 55C Queen Camel 1 (647/667) 77 Queen Fivehead 55C Sherborne 646 Camel Charlton Gillingham Galhampton 1 (647/667) Somerton 77 or 55C Horethorne 646 Ilchester 1 Marston Gillingham 647 South Cheriton 646 Magna Grove Farm 646 Sparkford 1 (647/667) 77 Ham Street 667 Templecombe 646 Mudford 646 1 Henstridge 646 Wincanton 646 or 647 646 Horsington 646 Wrantage 55C Sherborne Milborne Port Henstridge Huish Episcopi 55C Wyke 647 Yeovil Ilchester 77 Yenston 646 Keinton Mandeville 647,667 Yeovil 77 or 1 (647/667) Bus Routes, Operators & Departure/Arrival Times During term time to accommodate the additional 667 South West - Castle Cary to Strode College CD passengers travelling at peak times there is also an Total journey time 36 minutes, 7 stops CD 1 South West Coaches - Yeovil to Castle Cary additional college day service that departs Yeovil Bus Departs Horsepond 08:00. -

The History of Millfield 1935‐1970 by Barry Hobson

The History of Millfield 1935‐1970 by Barry Hobson 1. The Mill Field Estate. RJOM’s early years, 1905‐1935. 2. The Indians at Millfield, Summer 1935. 3. The Crisis at Millfield, Autumn 1935. 4. RJOM carries on, 1935‐6. 5. Re‐establishment, 1936‐7. 6. Expansion as the war starts, 1937‐40. 7. Games and outdoor activities, 1935‐9. 8. War service and new staff, 1939‐45. 9. War time privations, 1939‐40. 10. New recruits to the staff, 1940‐2. 11. Financial and staffing problems, 1941‐2. 12. Pupils with learning difficulties, 1938‐42. 13. Notable pupils, 1939‐49. 14. Developing and running the boarding houses, 1943‐5. 15. The Nissen Huts, 1943‐73. 16. War veterans return as tutors and students, 1945‐6. 17. The school grows and is officially recognized, 1945‐9. 18. Millfield becomes a limited company. Edgarley stays put. 1951‐3. 19. Games and other activities, 1946‐55. 20. Pupils from overseas. The boarding houses grow. 1948‐53. 21. The first new school building at Millfield. Boarding houses, billets, Glaston Tor. 1953‐9. 22. Prefects, the YLC, smoking. The house system develops. The varying fortunes of Kingweston. 1950‐9. 23. The development of rugger. Much success and much controversy. 1950‐67. 24. Further sporting achievements. The Olympic gold medalists. ‘Double Your Money’. 1956‐64. 25. Royalty and show‐business personalities, 1950‐70. 26. Academic standards and the John Bell saga. Senior staff appointments. 1957‐67. 27. Expansion and financial difficulties. A second Inspection. CRMA and the Millfield Training Scheme. 1963‐6. 28. Joseph Levy and others promote the Appeal.