J. Appendix 10: Relevant Articles and Documents

a. He Huliau – Shifting Paradigms: Imperatives For Hawaiian Cultural Survival, January 23-24, 2004 at Kamehameha Schools, sponsored by the Hui Ho‘ohawai‘i Assembly

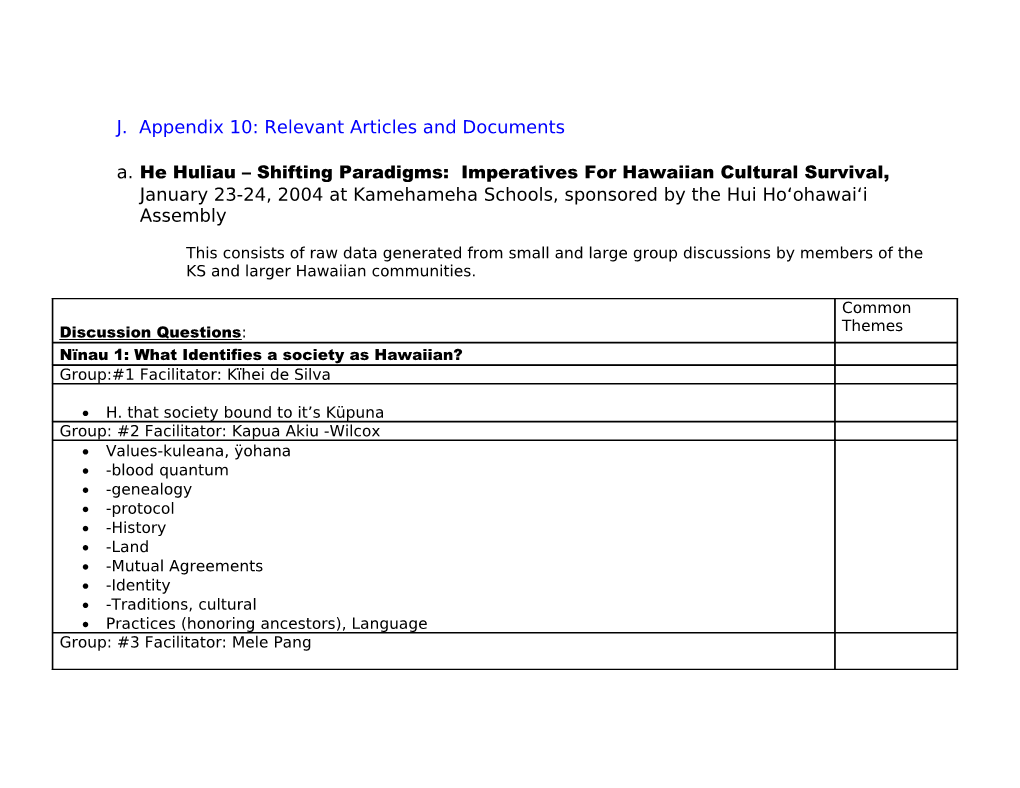

This consists of raw data generated from small and large group discussions by members of the KS and larger Hawaiian communities.

Common Discussion Questions: Themes Nïnau 1: What Identifies a society as Hawaiian? Group:#1 Facilitator: Kïhei de Silva

H. that society bound to it’s Küpuna Group: #2 Facilitator: Kapua Akiu -Wilcox Values-kuleana, ÿohana -blood quantum -genealogy -protocol -History -Land -Mutual Agreements -Identity -Traditions, cultural Practices (honoring ancestors), Language Group: #3 Facilitator: Mele Pang Language values (aloha) ancestry/genealogy Origins-relationship to land - land ownership/stewardship Stories – folklore. Music. Ritual. Ceremony. Religion/spirituality blood governance ahupuaÿa International recognition of nation state. Our interpersonal connections/ relationships hänai.

Group: #4 Facilitator: Kawika Makanani

Language – expresses nuances, richness of culture Unique activities e.g. specific food preparation, hula blood genetic genealogy, moÿo Aloha – respect, face-to-face unique experience and actions, hohonu -ÿoluÿolu

Group: #5 Facilitator: Ke‘ala Kwan

-Live & practice the culture -everything (people, etc) in that land – moving as one – the spirit -basic: the people -Behaving, gestures, way speak, how they interact -more than just hula, poi- it’s a life style – belief system, unity -moving as one – but we have (au kahi) individual talents, functions and you know your function

Group: #6 Facilitator: ‘Ululia Woodside ÿölelo, koko, moÿoküÿauhau, place- connection to wahi pana and ÿäina hänau just because you speak Hawaiian doesn’t make one Hawaiian) gives us the knowledge of our ancestors ÿölelo -justice – no one left out values practices responsibility to all

Nïnau 2: What makes a Society Vibrant? Group:#1 Facilitator: Kïhei de Silva -Vibrant society is defined by those who enjoy, are informed, pride and confidence, awareness For us to enjoy, etc… there must be a context (and we must be able to have it in a larger context – recognition, respect) Know history, grounded in tradition positive and negative (ex: lava flow) Creation, change / adaptation, evolving ( but with a mole) -Community begins with self and extends beyond; it consists of those who desire to belong to that community. Currently exists in Hawaiian families but connections have been weakened.

Group: #2 Facilitator: Kapua Akiu –Wilcox Dynamic, alive & practicing , kuleana

Group: #3 Facilitator: Mele Pang

“vibrant” pulsating with life, vigor, activity” -people speak language, practice culture. Youth are well cared fro, learning (küpuna ÿöpia connection interrogational ) growing. Produces products/services reflective of culture/ past, adaptive and functional in present with promise for future. Creativity of concepts, products, theories with understanding of societal history innovation plus tradition. Group: #4 Facilitator: Kawika Makanani Harmony with nature, land “vibrations” vibes Wahi pana Flourishing at all levels, arts, visible Self determination Active, positive ÿäina, kulaiwi means self-reliant independent

Group: #5 Facilitator: Ke’ala Kwan Vibrant – to be alive -Change -anything alive-noticeable, behavior and things we do -being constantly feed, nourished “cultural composting: from different sources -constantly working on something -certain amounts if inherent cultural pride-doing things that help this – difficult with so many things that make this difficult in society. -Catalytic in nature not fragmented every experience builds on another- alive more that just living- emanating affecting everybody else in the process.

Group: #6 Facilitator: ‘Ulalia Woodside

Nïnau #3 What makes a Hawaiian Society vibrant? Group:#1 Facilitator: Kïhei de Silva We are defined by our culture, but we have come away from it; we need to disclose how to evolve into this century to a re-identification w/ unique, endemic culture. -defined by feeling of attachment to ÿäina -define, perhaps, by what it is not. Group: #2 Facilitator: Kapua Akiu –Wilcox Practicing intellectual pursuit Constant intellectual pursuit Recognition by others/mutual respect Empowerment, take control of our community Growth of children Language Tension (küÿë) Culturally based education awareness/conscious shift in paradigms healthy opportunities

Group: #3 Facilitator: Mele Pang

-Language is spoken in homes, community, government -innovation that includes tradition our children are instilled with our language and culture they are taught these things they live our culture. -Our children have a Hawaiian world view -we are grounded in who we are, where we’re from -People “communicate” Hawaiian

Group: #4 Facilitator: Kawika Makanani Reservoir o f practitioners action opportunities learning küpunas, mälama, nä nana ike kumu systematic feelings, esteem within the lähui (ÿohana), and from others. (Küpuna have kuleana. Good to pass on ÿike, or to learn) Create attitude of speaking ÿike cultural strengths Borrowing technological literacy sometimes okay.

Group: #5 Facilitator: Ke’ala Kwan When Hawaiian society affecrs/touches others not Hawaiian – passion -looking back to parents and grandparents time (e.g. going to graveyard to mälama ÿohana) -maintaining kuleana/ÿohana -Nourish – “cultural compositing” -individual kuleana within our ÿohana doesn’t mean everyone did everything- fishermen specialty, hula specialty -there are basics shared by all Basics: Leo, movements, lawena manners, behaviors, values our ÿano Ability to adapt – no matter what we pursue- we can absorb and make it our own. Does a Hawaiian vibrant society only consist of Hawaiians? -If if culture is to live- larger mission it must involve others. -true lökahi – among elements: spirit, environment -go with that all -ÿäina based – “fertilizer” specifics -At same time Hawaiians have amazing ability to adapt yet preserve cultural values. Not all societies do this very well. Wonderful balance in Hawaiian society. -still battling assimilation. Good KS looking at this. If we don’t start I.D. and do the cultural composting. Group: #6 Facilitator: ‘Ulalia Woodside Do it, use it (with the foundation) Don’t just talk about it Need land (only people in Pacific- don’t control land) Need a place to exist Constantly evaluating, evolving Education What we want for every Hawaiian all speak Hawaiian (Child and teacher) Know küpuna, genealogy prepared to lead the nation whatever nation Oli & hula (mahiÿai Lawaiÿa, etc.) ready to practice Keiki w/ high esteem Availability of resources food ceremony ÿäina momna - adding, building growing Political analysis – critical analysis Leadership of Hawaiian society (pono) what does it look like? Group? One? Küpuna? Leadership must be Hawaiian Hawaiians speaking, sharing comparable, competitive globally. Nïnau #4 Why is a vibrant Hawaiian society a good thing? Group:#1 Facilitator: Kïhei de Silva

Group: #2 Facilitator: Kapua Akiu –Wilcox Survival of “us” -well being of all Hawaiians add to the quality of life in a global society. ( it is a blessing that Hawaiians are here in this world) Group: #3 Facilitator: Mele Pang

People have a strong connection to the homeland and are grounded in a Hawaiian world view

Group: #4 Facilitator: Kawika Makanani not all at same point Developmental, incremental, in pono way. Beauty, strength, positive ness of Hawaiian culture benefits Hawaiians and everyone else. Self Esteem Viable alternatives

Group: #5 Facilitator: Ke’ala Kwan All of #2 – Like kïpuka-no matter the obstacles we will continue to survive. gives pride to the community perpetuation when society is vibrant it fosters perpetuation of culture Oh my God this is Hawaiÿi Këia. Where else will find Hawaiians – we are alive. ÿO käkou këia Same as asking – “why are we important?” anything not nourished not important. Basic human wish to affirm and celebrate deep desire our individual lives – in group small or large. And that’s a good thing. We need to do it.

Group: #6 Facilitator: ‘Ulalia Woodside LARGE GROUP #1 Attributes of a Hawaiian Society: Facilitator: Kehau Abad a)Helpers: Mahealani Chang& Camille Naluai

-Reality of loss of Sovereignty Loss ÿäina, military invasion -Integrating elements of Hawaiian culture – many only have elements but not enough for wholeness. -Need active practitioners in society -Concept of I ( 1 for all, everyone vs. oneself) -Need a place to go to meet, work with practitioners -Oppression of Hawaiian ways -Take a space to lead toward taking our country back. -What is our long-term goal? If we’re looking at Kïpuka, let’s look at ex. KS Hawaiian staff trying to lead very difficult. -There is a society that created ke alii pauahi’s legacy -What is a society that will continue into the future. -Confusion of ID will make it very hard. -Fear too. *Expanding Kïpuka KS needs to be a strong Kïpuka KS has a role it must take KS has Pauahi’s legacy, money KS is the last place of Hawaiian Language, culture. *How do we make KS the Kïpuka of the mind? If KS in the past was a kïpuka there would have been 100,000 marchers instead of 10,000. -It’s hard because Hawaiians at KS do not have control. KS is struggling ….tribal unit would be better than “western best practices” – Hawaiian at Large Group # 2 Facilitator: Julian Ako 2. Helpers: Mahealani Chang & Camille Naluai ______ Implications for KS L.K.-Faculty/Staff speaking Hawaiian and knowing Hawaiian history (5year plan) K.E.- Late 1950’s and 60’s staff was taught Hawaiian history, culture, but in token; need to be goal- oriented and more sustained and in depth (i.e. Hawaiÿi Nui Kuauli) I.W.- Have Hawaiian Language requirement earlier middle school, elementary, pre-natal! H.P.- Don’t violate cultural values – feel, internalize akahai, haÿahaÿa, aloha-you do it and tha’s how you get it. Practice values. L.K.- bilingualism_ Hawaiian/English start at K and 12 years later those who come need to know there is a commitment to Language/culture and to give to the next generation… need to be able to analyze politics. M.P.- Education to Haumäna, values taught and practiced to become lifestyle not a curriculum goal- Lifestyle Change -Burden of teaching Hawaiian Language/ Culture should not be given to just one kumu need interdisciplinary hands ons, integrated. J.A. – Graduates serving Hawaiians at KS and elsewhere N.H.- KS Strategic Plan made commitments - ÿike Hawaiÿi. Mäori ex. Of Strategic till 3000 (tu whare toa) – Note: everyone must know about it (public awareness) we need to steps. K.E. – There is a willingness to require Hawaiian Language but how to get there is the problem – redefined values and destiny is key (i.e. choosing to stay in Hawaiÿi for college education) N.H.- Opportunity thinking; we need a good plan. Let’s use our resources. We know what our Küleana is. Hui Hoÿohawaiÿi is positive. Look at progress and gaps. Let’s make an action plan. L.K. – Finance – spend the money now ex. 500 million. Spend the money now on Hawaiians count how many bodies you need to do the work (i.e. teach ) and for the budget. Match Budget to the work plan. Action Pla

N.R.- KS work with Pünana Leo.

S.O.- Admissions experience (needed to rate keiki with varying levels of experience – distributing) (1) b. Historical Premise for the Existence of Kamehameha Schools

3. Overview Some two millennia ago, Polynesian voyagers discovered and settled the islands of Hawai‘i, giving birth to the Hawaiian culture. Centuries of innovation and refinement enabled this culture to attain some of the highest levels of achievement known in the Pacific. A conservative estimate indicates that the native Hawaiian population may have totaled 400,000 prior to foreign contact. However, recent studies show the likelihood of a much higher number of inhabitants as evidenced by the agricultural and aqua cultural infrastructure which had a carrying capacity capable of supporting between 800,000 and 1 million people.

4. Western Influences The initial impact of Western intervention was traumatic. New diseases ravaged the population. Between 1778 when Capt. Cook arrived, and 1823 when a census was taken by American missionaries, the Hawaiian population had dropped from 400,000 (conservative) to 132,000. By 1853, the native population declined further to 70,000. In addition, imperialistic actions resulted in a devastating sense of material and psychological loss. Throughout the 19 th century, Hawaiians became increasingly disenfranchised from their land and its resources which had sustained them in isolation for nearly 2,000 years.

In an effort to stabilize and maintain Hawai‘i as a sovereign nation, the Hawaiian monarchy created social and political alliances with royalty and heads of state from throughout the world and ratified treaties with foreign governments. It established constitutions that it hoped would protect the Hawaiian kingdom from foreign control. It was precisely these historical circumstances that inspired Ke Ali‘i Bernice Pauahi Bishop to establish Kamehameha Schools in 1884. It was her hope that education would help Hawaiian people to cope and survive in an increasingly non-Hawaiian world. However, by 1893 Americans' burgeoning political and economic interests in Hawai‘i and its resources peaked, and Hawai‘i’s last monarch, Queen Lili‘uokalani, Pauahi’s hänai sister, was unlawfully overthrown. By this time, the population had dwindled to about 40,000. Though opposed by the majority of Hawaiians via petition, Hawai‘i was annexed as a territory of the United States in 1898. Over a century later, the legality of this action continues to raise questions in contemporary times.

Downward Spiral From the turn of the 20 th century to the dawning of the 21st, Hawaiians endured a hundred years of forced assimilation into mainstream American culture and lifestyle. Despite indications that the Hawaiian kingdom was one of the most highly literate nations in the world in the latter half of the 19th century, the Hawaiian language was banned from the public and private school systems in 1896 and it remained an unrecognized language by the government for nearly a century. The English-only legislation was among the most destructive colonial acts against native Hawaiians -- it resulted in a precipitous decline in the indigenous understandings of their own culture, history, values, spirituality, practices and identity as a people. The effects of colonialism and institutional racism continued into the 1920s (when only 24,000 native Hawaiians were left), became imbedded in Hawai‘i’s system during World War II and remained through statehood in 1959. 5. Toward Cultural Stability: Restoring the Values, Soul and Psyche In the years following statehood, a surge in tourism and an influx of new residents drastically altered the social and natural landscape of Hawai‘i, threatening the survival of the then fragile Hawaiian culture.

Then, the tide began to turn during the decade of the 1970’s which was marked by a dynamic movement by Hawaiians to hold fast and reconnect to their cultural roots found in the environment, in themselves and in their past. Hawaiian language, arts, values, perspectives and socio-political activism, became widespread – it was an era of great cultural pride. And yet even the colorful and festive Hawaiian Renaissance could not upstage the debilitating effects of 200-plus years of political, social, cultural and psychological trauma. Today, in 2003, as Hawaiians continue to be disproportionately represented in social statistics regarding poor health, unemployment, incarceration, education, and so forth, they also remain, for the most part, culturally illiterate as a people and are generally disconnected from their ancestral heritage and lifestyle on a daily basis.

Moreover, the values and practices of our ancestors shaped by an island home and subsistence economy, nurture an understanding of the need for sustainable resource management and of the importance of placing community benefits above self-interest. These values are as or more relevant in the 21 st century as they were when Polynesians made their first landfall in Hawai‘i Nei. KAMEHAMEHA SCHOOLS’ KULEANA

Given the premise of history and the promise of our future, it is the goal of Kamehameha Schools to:

Work towards the reestablishment of social and cultural stability through the restoration of Hawaiian cultural literacy for native Hawaiians of all ages;

Facilitate Hawaiian cultural learning throughout the Hawaiian community;

Institutionalize Hawaiian cultural perspectives and practices throughout the Kamehameha Schools system;

Promote the globally accepted understanding that the condition of indigenous peoples is directly impacted by their access to resources, their positive feelings of self and group esteem, their sense of identity, and grounding in their own native culture.

Collectively, these form an important catalyst for the success and the rightful advancement of Känaka Maoli, native Hawaiians, in their own homeland in the 21 st century. Kamehameha Schools, by virtue of its history and educational and cultural mission, is committed to the education of native Hawaiians not simply for education’s sake, but ultimately to improve the conditions of native Hawaiians and to ensure their longevity as the indigenous people of Hawai‘i.

c. Kamehameha Schools As A Hawaiian Institution

1. Definition of a Hawaiian Institution: A Hawaiian institution is an extended family that manifests its identity through beliefs and practices rooted in an ancestral Hawaiian worldview.

2. Purpose of a Hawaiian Institution: The purpose of a Hawaiian institution is to empower Hawaiians.

3. Purpose of a Hawaiian Educational Institution: The purpose of a Hawaiian educational institution is to facilitate learning that empowers Hawaiians to thrive as a people who are grounded in their culture and committed to its practice, perpetuation, and growth.

Kamehameha Schools commits itself to the purpose of a Hawaiian educational institution.

4. Kamehameha Schools affirms its identity as a Hawaiian Educational Institution by promoting and exemplifying the following attributes from an indigenous perspective: Spirituality

‘Ölelo Hawai‘i (Native Hawaiian language)

KS genealogical identity

Human relationships in the learning and working environments

Use of resources (e.g. people, land, knowledge and wisdom, money)

Educational philosophy and practices Cultural beliefs and practices

Decision-making/governance/policy

Systems of measurement and evaluation 10/2002

d. Hawaiian Culture At Kamehameha Schools

A Position Paper Submitted by the Hui Ho‘ohawai‘i Assembly to the Kamehameha Schools Board of Trustees, Acting Chief Executive Officer and the Interim Vice Presidents of Education and Legal Affairs, September 23, 2003

DEFINING "HAWAIIAN CULTURE"

Hawaiian culture refers to the totality of human activity characteristic of the traditions, customs, spiritual beliefs, aspirations and worldview of the indigenous people of Hawai‘i. It is irrespective of time (not just in the past but also in the present), and in some cases, irrespective of place (not just in Hawai‘i, but also elsewhere). Notwithstanding, Hawaiian people feel closely connected to their ancestral past and view themselves as being genealogically connected to the pae moku (island chain) of Hawai'i. Hence, references to the past and to locations in Hawai‘i are important ways Hawaiians all over the world affirm their identity as being "Hawaiian." Ultimately, “culture” is the unconscious acting out of life. Our collective goal to revitalize and reestablish Hawaiian culture, in essence, implies that we are working toward a state where Hawaiian lifestyle becomes natural, and can be looked upon as normal, commonplace and pervasive throughout all of society.

A living culture is about “people,” not about acquiring "knowledge." The learning of information, while valuable, is not an indicator of life. For example, there is much information available about the ancient Maya of Central America. We know about their language, social structure, religion, delicacies, attire, ceremonies, agricultural and architectural achievements, and much more. But the Mayan civilization is not a living culture, it no longer exists. There is no vibrant community that defines the Mayan people, today. In our case, we have a lot of knowledge about the Hawaiian culture, and there has been much emphasis placed on the learning of cultural information. However, there is considerable difference between “knowing about” a culture (i.e., as in the Mayan case) and participating in a living and breathing culture. Hence, to truly perpetuate Hawaiian culture, we must look at the social and cultural vibrancy of our people, and not focus on knowledge acquisition alone.

Hawaiian culture is alive when people representing a wide range of Hawaiian cultural beliefs, behaviors and practices coexist and interact together as a way of life. When this occurs in a fertile environment, that is, an environment sufficiently versatile to foster interactivity among a broad range of cultural elements, culture can become dynamic and vibrant with a strong likelihood for growth. Often, we describe the presence of Hawaiian culture where in fact there exists only an element, one small part, of Hawaiian culture. For example, when we refer to Hawaiian language, hula, farming taro, or sailing a canoe in isolation from their larger cultural context, we need to constantly remind ourselves that none of them is Hawaiian culture, per se. Briefly restated, the existence of Hawaiian culture requires: 1) a wide range of cultural beliefs, behaviors and practices characterized as Hawaiian, and, 2) interactivity and coexistence among those cultural elements to form a way of life. The survival of Hawaiian culture is dependent on fertile environments that accommodate a wide range of cultural elements and promote coexistence and interactivity.

Hawaiian Subcultures

To the degree they encompass a range of cultural interactivity in fertile environments within their own specific domains, certain Hawaiian cultural practices can and have developed into subcultures. Hula and Hawaiian language learning represent thriving subcultures that exist as independent entities.

Hula, for example, through the hälau context, combines a wide range of cultural elements such as Hawaiian language, history, knowledge of native plants, spirituality, and so forth, and promotes interactivity at a very high level (e.g., myriad hälau, hula competitions locally and abroad, etc.). Likewise, the study of Hawaiian language can include a range of cultural experiences that involve history, culture and the arts. There are thriving communities that maintain the practice of hula and Hawaiian language; both elements possess the necessary attributes for survival. However, they are "subcultures." They do not constitute "Hawaiian culture" by themselves, they are simply parts of a much greater whole.

"Elements of Culture" VS. "Culture"

While there are many examples of the perpetuation of "Hawaiian cultural elements" in our community, there are surprisingly few examples of the perpetuation of "Hawaiian culture." That is to say, there are few fertile environments within which a wide range of cultural elements coexist, interact and thrive as a way of life.

Examples of "cultural elements" include the gamut of activities and practices such as language learning, hula, chanting, singing, composing, storytelling, surfing, canoe paddling, voyaging, lua, carving, farming, fishing, cooking, visual arts, healing, conflict resolution, ceremonies, etc. There are hundreds of programs in schools, churches, organizations and throughout the community, as well as on television and on the Internet, that facilitate the learning of, or participation in, cultural activities.

On the other hand, the existence of "Hawaiian culture" (as defined here) is much more rare. A number of culture-based charter schools (e.g., Hälau Kü Mana, Kanu o ka ‘Äina, etc.) have created very fertile environments where Hawaiian language, biology, farming, English, fishing, history, math, kapa-making, economics, poi-pounding, astronomy, hula and more, consistently interact to form a Hawaiian lifestyle for students, staff and the administration. Näwahïokalani‘öpu‘u is a stellar example of a very fertile environment that promotes an indigenous Hawaiian worldview (honua mauli ola) and operates entirely in the native Hawaiian language. Kamehameha Schools Hawai‘i Campus at Kea‘au, while its academic standards are aligned with western paradigms, has established itself as a learning community with a Hawaiian cultural foundation. This is evidenced in the fairly high degree of cultural interaction at all levels, and is supported by its culturally rich community environment which is home to a high percentage of native Hawaiians.

These few "pockets of Hawaiian culture" within Hawai'i's largely western society can be viewed as kïpuka. They are like small life-sustaining oases scattered sporadically amidst an overwhelmingly vast and barren landscape of lava. Collectively, these cultural-educational kïpuka are important microcosmic models of what could and perhaps should be happening on a greater scale to affect a much larger population of native Hawaiians, and non-Hawaiians, as well. Such kïpuka are not only critical to the vitality of the Hawaiian people, but also have economic implications for the state. Recent discussions about reviving our tourist industry, focuses on the important role of Hawaiian culture to these efforts.

Why Aren’t We Creating More Fertile Environments?

Why is there an overwhelming amount of attention on preserving individual elements of Hawaiian culture and very little attention on creating environments where those elements can come together to form a dynamic Hawaiian cultural whole?

One answer might be the social, political and psychological effects of colonialism. In traditional times, identity, ancestry, beliefs and behaviors were reinforced by the ‘ohana, the extended family community. Once the bedrock of society, this ‘ohana network served as a critical socio- cultural support system. However, western intervention dismantled Hawaiian society so severely that now, mere remnants are left of the richness that once existed. Today, Hawai‘i’s social landscape finds many native Hawaiians at or near the lowest rungs of a western-based society. Ongoing disenfranchisement from their land and its resources compounded by the absence of their own indigenous socio-cultural support system has left most native Hawaiians culturally depauperate. With increasing western encroachment and the rapid passing of küpuna and traditional lifestyles, Hawaiians seem to be in "preservation mode” on a regular basis; they are constantly overwhelmed with keeping parts of themselves alive. To use the metaphor of a trauma victim, Hawaiians are so busy trying to stop the bleeding that they are often unable to address other vital functions key to the survival of their culture.

Statistically, just keeping Hawaiians alive is a task in itself. But is physical survival enough? The Hawaiian community says, “No.” A key part of their survival and well being is remembering who they are: their identity, their ancestral connections to the land and their way of viewing the world. Hence, "preservation" and "perpetuation of cultural elements" alone are insufficient. If Hawaiian culture is to survive, Hawaiians need to be "reassembling" their culture and piecing themselves back together. To do this, they need culturally fertile environments where they can regenerate their culture and establish their socio-cultural support systems once again.

Another factor for the focus on cultural fragments as oppose to cohesive systems, may be the proliferation of a western worldview. Over time, both Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians alike have become used to seeing Hawaiian culture broken up into sections like units in a history textbook, or like showcases in a museum with brief captions below each exhibit. Hawaiians have become accustomed to framing their history in reference to the arrival of foreigners and foreign events and not as a dynamic continuum of Polynesian achievement over the course of millennia. And, sadly, some have come to accept the flawed notion that the deterioration of Hawai‘i’s indigenous culture was inevitable – simply a natural course of events for inferior ways of life. As a result, it simply does not occur to many Hawaiians that it is even possible to create a cohesive cultural existence as an indigenous people in the 21st century.

The lack of cultural connectedness and a clear vision for the Hawaiian people may preclude the application of innovative and creative thinking. The reestablishment of Hawaiian culture may heighten feelings of inadequacy among culturally detached Hawaiians, thus leading to lukewarm or non-support of viable avenues for cultural regeneration.

A final compelling reason might relate to resources. The vision to regenerate and develop a vibrant Hawaiian society may be beyond the thinking of some leaders in the Hawaiian community. Instead, there is the strong misconception that simply funding "something Hawaiian" (or in KS nomenclature, 'Ike Hawai'i) is somehow perpetuating the indigenous Hawaiian way of life. Lastly, it is much cheaper to fund an activity or a program than it is to rebuild a Hawaiian community and to reestablish the multi-faceted culture of Hawai‘i's native people.

B. THE DANGER OF MISREPRESENTATION

There is great danger in saying that the "Hawaiian culture is being perpetuated" when in fact there is only the "perpetuation of cultural elements and activities." Doing so creates false impressions regarding the true condition of Hawaiian culture and the cultural well-being of native Hawaiians. This would be analogous to purposely implying that someone is in good health when you are aware that he or she is not well -- it is unethical.

When the general public views the Merrie Monarch Hula Festival, reads an article on children planting koa, or watches breathtaking footage of the Höküle‘a on television, they can be led to think that Hawaiian culture is alive and well. When it sees a commercial for Pünana Leo Preschools or notices an article written in Hawaiian in the newspaper, it thinks that the Hawaiian language has been saved. Likewise, when people flip through the Kamehameha Schools strategic plan, see an ad for Pauahi's Legacy Lives, watch I MUA TV or tune in to the Song Contest, the impression is that Kamehameha Schools is doing a lot to perpetuate the way of life of the indigenous people of Hawai‘i. Generally speaking, public perception may be that Hawaiian culture is strong and on the upswing, when in reality its prognosis for survival may be quite precarious.

II. Perceptions vs. Reality: Kamehameha Schools

Generally speaking, when we apply the conditions of culture to Kamehameha Schools, we find that there are opportunities for Hawaiian cultural education through various programs and initiatives. These include courses, workshops and activities that involve Hawaiian language, history, culture, dance, etc. There are also a few unofficial cultural kïpuka where limited numbers of students, staff and community members can have brief Hawaiian cultural experiences. At the same time, members of the Kapälama Campus community report that daily life at Kamehameha essentially reflects a western-based culture as evidenced in the overall curriculum, school-wide learning expectations, policies, employment practices, finance/budget philosophies, organizational structure, communications, daily operations, etc. Hawaiian cultural interaction and practices are quite uncommon among students, staff and the administration, and large-scale high profile events (e.g. Song Contest, Founder’s Day, etc.) provide only limited cultural exposure.

Kawaiaha‘o Plaza, the Schools corporate center, is dominated by western-based culture. Hawaiian cultural practices and interaction are generally non-existent with the rare exception of sporadic Hawaiian presentations and observances. Most programs, policies, procedures and benchmarks seem to reflect practices and perspectives commonly found in businesses throughout the U.S. mainland. Generally, both Kapälama and Kawaiaha‘o seem to cultivate western culture well.

With nearly the entire student population of all KS campuses, as well as KS’ community-based target audiences being ancestrally Hawaiian, and given the fact that the resources to found the Schools were bequeathed by a Hawaiian chiefess to improve the conditions of her severely disenfranchised native Hawaiian people, there is reason to conclude that the overall range of Hawaiian cultural elements, practices and cultural interactivity at Kamehameha Schools is alarmingly low.

There is a strong desire within the Kamehameha community for KS to maintain a certain “Hawaiianess.” Towards this end, there are conscious attempts to integrate the significantly more dominant western sphere with the considerably less-defined Hawaiian sphere. The results are mixed. On the upside, Hawaiian cultural consciousness has been raised considerably. KS sponsors a number of activities and programs that deal with elements of Hawaiian culture for the benefit of students, staff and the greater community via a variety of media. This is by no means a new endeavor; there have been key individuals and model programs over the many decades that have fostered appreciation and respect for Hawaiian culture even during eras when doing so seemed less important to the community. Today, there are increasing numbers of culturally literate people who advocate for, and serve as resources in, departments and offices throughout Kawaiaha‘o Plaza, Kapälama Campus and elsewhere within the institution. Land Assets Division, which, in its former state, ran a solely revenue-driven operation, is now beginning to promote indigenous concepts of environmental stewardship as well as foster a community-oriented lifestyle of native Hawaiian resource management. While the present cultural environment is still inconsistent and much work remains to be done, the drive to do more Hawaiian things reflects a sincere desire on the part of the institution to truly honor the culture of Pauahi’s beneficiaries.

At the same time, the effort to project an authentic Hawaiian institutional persona has given rise to what some perceive to be cosmetic approaches to Hawaiian culture. For example, the Schools’ strategic plan directs that attention be given to ‘Ike Hawai'i (Hawaiian cultural knowledge), but no plan or mechanism is in place to guide, assess or project a vision for Hawaiian cultural outcomes at this time. A campaign on Hawaiian values has raised community consciousness regarding a selective group of Hawaiian concepts. However, the institutional messages sent to both internal and external audiences, as well as KS' overall climate, are often perceived as inconsistent with the Hawaiian values and virtues being promoted. Hawaiian performing arts have projected strong and powerful cultural statements on stage. However, most students' behaviors, attitudes and aspirations off-stage are more closely attuned to American pop culture. Many students at the Kapälama campus perceive Hawaiian language and cultural practices as somewhat foreign and some are unable to articulate attributes of their own Hawaiian heritage and identity when called upon to do so, even in their senior year. Yet, despite these challenges, Kamehameha Schools is committed and genuine in its desire to meet the educational needs of Hawaiian children and may possibly be on the cusp of a new Hawaiian cultural movement.

Overall, the following generalizations can be made: Kamehameha Schools supports and perpetuates "elements of Hawaiian culture." Kamehameha Schools as an institution, does not, at this time, actively perpetuate "Hawaiian culture," as defined here. That is to say, KS, generally speaking, does not appear to be a culturally fertile environment that promotes the holistic interaction and coexistence of a wide range of Hawaiian cultural beliefs, behaviors and practices to form a cohesive and viable native Hawaiian way of life for the indigenous people of Hawai'i. In short, Hawaiian culture is not a way of life at Kamehameha Schools.

III. Recommendations Regarding Hawaiian Culture At KS

1. Distinguish Between "Elements of culture" and "Hawaiian culture:" a. KS should distinguish between perpetuating "elements of culture" and perpetuating "Hawaiian culture," as appropriate and practical. b. KS should not create the impression that it is engaging in a high degree of "cultural perpetuation" when in fact, only isolated cultural elements and activities are involved, and because Hawaiian is not truly the practiced culture of the institution on a daily basis.

2. Embrace a Native Hawaiian Cultural Paradigm: a. KS should focus on the creation of fertile environments, kïpuka, to foster the regeneration of Hawaiian culture. b. KS should focus on cultural "contexts" not just cultural "fragments" c. KS should focus on the "reassembly" of cultural elements to form a cohesive whole and not just the "perpetuation” of cultural elements in isolation. d. KS should consider Nohona Hawai'i (Hawaiian cultural living/lifestyle) in addition to 'Ike Hawai'i (cultural knowledge), as a strategic mandate. e. KS should consider an organizational transition from an institution that grooms Hawaiians to be western and to succeed in a western world, to an institution that grooms Hawaiians to be Hawaiian in order to succeed in all worlds. (See Nä Honua Mauli Ola : Hawai‘i Guidelines for Culturally Healthy and Responsive Learning Environments)

3. Fully Integrate ‘Ike Hawai‘i/Nohona Hawai‘i a. KS should develop vision, goals and outcomes for Hawaiian culture as it implements the strategic plan. b. KS should create a bona fide mechanism to facilitate institution-wide integration of Hawaiian culture.

4. Establish Hawaiian Cultural Centers a. KS should establish Hawaiian cultural kïpuka,centers, on all three KS campuses. b. KS should immediately establish a community-wide Hawaiian cultural center at the Kapälama campus, since plans are already in place and because the scope of the Kapälama site can potentially impact a considerably large population of native Hawaiians quickly and effectively. c c. KS, generally speaking, currently educates Hawaiian children to d become western, which is more aligned with historical injustices against Hawaiians. KS should modify and broaden its focus and assist Hawaiian learners in becoming reconnected to, and grounded in, their own indigenous culture, which is more aligned with righting past injustices against Hawaiians. Cultural centers and their programs will help to reestablish the socio-cultural support system that was historically undermined by westerners d. KS should consider the fact that even if it wins the two current admissions lawsuits, more suits are likely to come. The continued lack of a Hawaiian cultural base at Kamehameha Schools potentially weakens our case in that there is inconsistency among our legal positions. e. KS should consider the consequences of possibly losing the two lawsuits. Should non- Hawaiians be allowed to attend Kamehameha, the Hawaiian cultural centers and their programs will be even more critical. The centers will provide very fertile environments with high levels of cultural interactivity to regenerate the lifestyle of the indigenous people of Hawai‘i. This will tend to attract high numbers of native Hawaiian applicants to the Schools, thus enabling KS to still address the target audience Pauahi intended, yet be in legal compliance.

5. Kapälama Campus Hawaiian Cultural Revitalization, HCCP Discussion

Questions IV. Responses

A. 1. What would make Kapälama Campus Everyone behaving with ‘ano Hawai‘i—not only knowing Hawaiian philosophy, values and a Hawaiian place? practices, but acting upon them; also having opportunities to practice them.

Philosophically, a Hawaiian place is more felt than it is seen. To have a place that looks Hawaiian would be to have classrooms outside, where the students learn about weather and plants by walking around and feeling those things. Considering the current physical make-up of our school, this campus could be made more Hawaiian by providing our students, faculty and staff with a place that they can go to, to learn and “be” Hawai‘i. . . HCC

If the campus were organized in a way that enabled all members of the community to interact like an ahupua‘a. There should also be a common gathering place, other than Kekühaupi‘o that would enable the practice and support of Hawaiian activities.

Using Hawaiian Language where ever and when ever possible.

Leadership proficient in language, values, practice and protocol.

Finding and increasing ways to teach through culture rather than teach about culture.

Reinstating and practicing traditional observances.

Incorporating traditional spirituality along with current Christian spirituality.

Instilling traditional values relating to deep respect for place, property, teachers and kupuna.

Opportunities to engage in practices, protocols and experiences. Do it Hawaiian whenever there is the need to do something.

Everyone learn the importance of mo‘oküauhau, learn the Kamehameha family genealogy and the connection to KS lands.

We need to display Hawaiian art all over the campus: small pieces and large, three dimensional and flat, functional and fanciful, traditional and envelope-pushing, awesome and god-awful, in places obvious and secluded, indoors and out, expected and unexpected. Some of these pieces should be part of a permanent and ever-growing collection, others should be temporary, and others should be displayed in-progress. We need to showcase the work of students, staff, alumni, and select artists- in-residence. We need to make Hawaiian art (as with Hawaiian language and Hawaiian intellectual activity of all kinds) central to campus life: unavoidable, inescapable, ubiquitous, and alive. This, when it happens, will reflect a campus-wide commitment to the vibrancy of Hawaiian culture. The current absence of Hawaiian art at Kapälama (except, of course, behind glass cases and in the few and far between kïpuka of enlightened thinking) contributes much to the still non- vibrant, still non-Hawaiian ‘ano of the place.

The campus needs to be replanted and our relationship to the ‘äina redefined. The campus is beautiful in a well-manicured, western sense – but it gives too little evidence of aloha ‘äina, of a people’s actual attachment and commitment to the land. Yes, there are places on campus that are landscaped with Hawaiian plants: the laua‘e beds at Konia Circle, the ‘äkia at the Heritage Center, and the ‘öhi‘a lehua on the slope above Kekühaupi‘o, for example. But the dominant impression-even where the plants are native-is that of “estate” rather than “mäla,” of grounds crew rather than gardener, of scenery not of source. A concerted effort to replant the campus in natives would go far to soften its plantation- manager’s ambience, but we need, in the long term, to move beyond the kind of ornamental Hawaiian landscaping that is designed, installed, and maintained solely by people who are hired to do these things. If the campus is to be a Hawaiian place (as opposed to a showcase of Hawaiian plants), then we Kapälama pono‘i – students, parents, alumni, staff-have to turn our palms down and share responsibility for an actual reciprocal relationship with the land. The thinking of Kumu Hans’ mäla ‘ai at Keöua needs to be nurtured and adopted system-wide. We need mäla of this sort in every place possible- places where we plant and tend palapalai, lehua (any maybe maile!) aslei plants, places where we plant and tend koa for Kamehameha canoe- makers yet unborn, places where we learn to propagate ‘iliahi from seed, places where we grow and investigate the medicinal properties of ‘uhaloa and other kinolau of Kamapua‘a. Attention needs to be given, as well, to the transformation of outdoor spaces into thinking- gathering-working-interacting places. Places small and larger, informal and less informal, covered and uncovered. Places conducive to learning but removed from conventional western learning environments. All told, these mäla and o‘io‘ian (shaded resting, stopping places) will demonstrate a campus-wide commitment to nohona Hawai‘i, to a vibrant sense of Hawaiian culture in which ‘äina is central to sustenance and learning-not just ornamental, not just pretty scenery outside the classroom window.

2. What would make Kamehameha Schools a Same as above but applicable to the entire Hawaiian school? institution: Everyone behaving with ‘ano Hawai‘i- not only knowing Hawaiian philosophy, values, and practices, but acting upon them; also having opportunities to practice them.

Hawaiian students (we need to support every effort to keep Kamehameha a school for Hawaiians, as well as a Hawaiian School)

Hawaiian Mana‘o-School mission and curriculum should reflect the needs of the students and community that we serve. Teachers, administrators and support should be familiar with Hawaiian values and customs to better teach the students.

Hawaiian Language-needs to be treasured and language education needs to be supported at all levels (accommodating staffing needs to educate every child in our ‘ölelo makuahine)

If the mentality of administration, faculty, and staff had a more Hawaiian perspective regarding the purpose and objectives of the school’s programs. (i.e. The Kamehameha Schools Leadership program should concentrate on Hawaiian Leadership, with student leaders being able to greet and host dignitaries following Hawaiian protocol.)

Using Hawaiian Language where ever and when ever possible.

Leadership proficient in language, values, practice and protocol.

Staff development on Hawaiian values and philosophies so that Hawaiian views and priorities become the focus in any decision making process.

Promoting and engaging in experiences to participate in Hawaiian practices, protocols, and customs.

Staff development to learn Kamehameha family genealogy, the genealogy and lineage of KS lands, and the importance of knowing one’s own genealogy.

Supporting, valuing and elevating Hawaiian ways over the Western corporate. Example: value and elevate the käkou work over the individualistic.

Build that connection with the ‘äina. It is this place that has made us who we are. As Polynesians who first set foot on this ‘äina, it was the 90% endemism found on these islands that shaped the Hawaiian. It is these lands, the winds, rains, plants and animals that make us unique, and make us Hawaiians.

3. How do the HCCP mission/vision statement, It is a vital component-life is vibrant, our society “Ensuring a Vibrant Hawaiian Society” relate to needs to be alive-doing, being, becoming, birthing, creating for the present and future. the discussion of KS becoming a Hawaiian school? This mission statement is the backbone of all that we hope to accomplish here at the school. More emphasis is put on student outcomes with respect to the long term good it will do for that individual as well as for the Lähui Hawai‘i. Graduates will know their history, language and culture; and perpetuate it through their actions after they leave the school. This pride in themselves and their culture will carry over into any profession the decide to pursue, always remembering their roots and giving back. If the mission/vision of the HCCP is accepted by the entire school community, there will be a different focus for the student that would align with the goals of the school. (Body, Mind, Spirit, World) Students will know who they are as Hawaiians and with this strong foundation is able to take progressive steps in the Western world.

HCCP can be the catalyst and the model.

HCCP can provide guidance.

4. What is the HCCP’s role? HCCP is-even if by default-the primary engine that will drive KS to its destination. The vision of its leaders, the na‘auao of its members, and the commitment of all, are not found in any other KS group. HCCP is the piko of our cultural resurgence. It can be considered the facilitator of all cultural practices on campus. HCCP can be used as a resource for those who seek information or wish to share information.

The role of the HCCP is to ensure that all levels of our institution are willing to take steps to ensure that the mission/vision is carried out for the benefit of the Hawaiian community that Kamehameha Schools serve. 5. What would make Kamehameha Schools a HCCP needs to continue pushing the envelope, Hawaiian organization system-wide? along with other KS groups and individuals. The vision and commitment of the decision-making, budget-controlling leadership is vital in providing paths of possibilities. They are generally out of touch, so others need to prod then and be ready to kökua & käko‘o.

Understanding of Nohona Hawai‘i. Hawaiian leaders with Hawaiian mana‘o.

To develop a system-wide Hawaiian organization steps need to be taken to ensure that all members of the institution agree with the statement that “Kamehameha Schools should be a Hawaiian School.” If this statement is agreed upon, then steps can be taken at every level of the institution to ensure Kamehameha Schools is fulfilling its kuleana of “Ensuring a Vibrant Hawaiian Society.”

Hawaiians in leadership roles.

Leadership adept and proficient in all aspects of Hawaiian life ways/culture (‘ölelo, pule, alaka‘i, ha‘aha‘a, ho‘okipa, laulima, etc.)

Hawaiian values and relations take precedent in all decision-making processes. We look to ourselves and our community for strength and leadership. We don’t look to the continent for the answers or as the model.

Record our current events through mele and mo‘olelo ma ka ‘ölelo makuahine. We are the history makers, let’s leave a record of our events and deeds as our küpuna did for us.

We treat each other, staff, teachers, students, alumni, etc. as family members. We work together and care for one another as a family. We make our work environment a healthy place. Slow down; make sure family, friends, spirituality, fun are a priority, not second to our corporate nature.

We develop a relationship with our ‘äina, both KS ‘äina, and those places which are special to us as individuals.